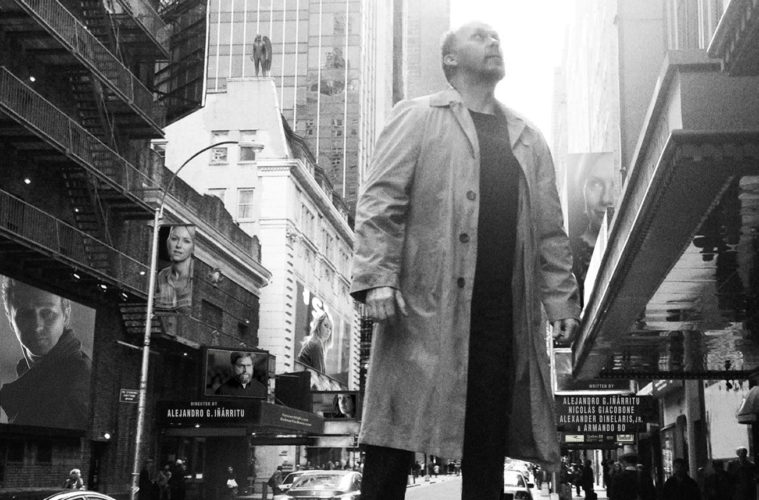

Kicking off the 71st edition of the Venice Film Festival this morning, Alejandro González Iñárritu‘s Birdman has all the markings of a great festival opener: it represents a departure in style from a controversial director, a good four years after Biutiful; it’s got a juicy cast of actors, all testing themselves in different ways, and it comes wrapped in that crazy cinephile mystique that leaves people speculating for months about a continuous long take that may or may not make up the whole film.

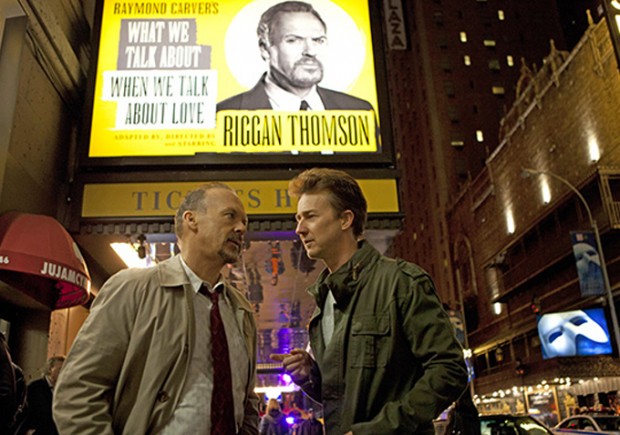

Well, Birdman is certainly all that, down to the jazzy, vibrant single-take effect employed by Iñárritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki to chronicle the early days of a Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver‘s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Writing, directing and starring is Michael Keaton‘s Riggan Thomson, who comes from the movies and used to play a superhero back when everyone else wasn’t. His “Birdman” franchise is long forgotten, and in turn they’re “putting a cape” on all the good actors out there, so Riggan is betting his career (and perceived artistic legitimacy) on something that truly matters. With his best friend (Zach Galifianakis) as a producer and estranged daughter (Emma Stone) as an assistant, Riggan has to get the play and the cast (Naomi Watts, Andrea Riseborough, Edward Norton) ready for opening night and for that dreaded, make-or-break New York Times review.

Defined by its own snowballing eccentricity, Birdman has too many balls to juggle around, though admittedly its protagonist does too. The extent of the film’s thematic canvas – reality vs. representation, personal suffering as artistic transcendence, a dash of contemporary movie business satire – mirrors the trajectory of the man’s psychological breakdown, even if he weren’t talking to an imaginary version of himself in full Birdman costume and Bale-like (nice touch) growling voice, or channeling his rage into telekinetic powers.

Maybe Riggan is just a washed-up Hollywood hack after all, and Birdman is a version of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York in which the terrifying endgame is a blockbuster’s third act instead of the gloomy existentialism of the universe. But in what probably is Iñárritu’s best film to date, this is thankfully mixed with a more tangible exploration of the individual-as-performer. It calls to mind Aronofsky’s double-gender take on the subject (The Wrestler and Black Swan) with its emphatic dissection of Keaton’s body, pain and flesh. But it is also capable of opening up to the collective: despite a close focus on Riggan, Iñárritu is fascinated by the voracious addiction to stage thrills that consumes Mike Shiner (and what a showcase for Norton this is) as well as the endless bits of behind-the-scene emotional camaraderie — both fun and heartbreaking — that at times resemble Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion.

The reason this all works remains Lubezki’s approach, which is the true main attraction of the show. The much-anticipated long take soars beyond much more than a gimmick, and in combination with the penetrating drumbeat score (so penetrating, in fact, to twice break into the frame) it collapses time and space into the exciting illusion that the film is taking place in the split-second before the curtain comes up. This is the second Venice opener in a row for Lubezki after last year’s Gravity, and his style is integral here as it was there. Shooting almost exclusively within the confinement of a single Broadway theatre (it’s worth noting that Iñárritu’s regular lenser Rodrigo Prieto provides some additional New York cinematography here) the camera uses every trick in the book to maintain continuity without rigidly adhering to it. One minute it moves to follow, and the next it’s wandering off, doing its own editing and loosely playing with the passage of time. It’s probably no coincidence that Birdman falters a bit by opening things up in the last few minutes, indulging one super-fantasy too many.

Birdman opened the 2014 Venice Film Festival and will be released on October 17th.