By modern standards, Quentin Tarantino would be considered an auteur; a director whose films reflect his personal creative vision. But what exactly is that vision, and how is it reflected in his work?One major observation that one can make about Tarantino’s films is that he often incorporates a number of references, many of which refer to cinema, specific films, or pop culture. His films are laced with this intertextuality were the relationship between texts (or films) is constantly being redefined. This method of pastiche is one way that he draws attention to the fact that his film is a constructed piece of fiction, or a “simulation.”

His rational behind this is heavily influenced by French theorist Jean Baudrillard’s notion of “hyperreality.” Hyperreality in this case refers to the inability of consciousness to distinguish reality from fantasy, as the two become blurred into one. Baudrillard argues that today we only experience prepared realities, such as edited war footage and reality TV show; one is unable to distinguish between what is true and what is fiction. Tarantino plays with this idea, mixing references and popular images with reality, creating a mixture that is his own reality in the process.

His most recent production, Inglourious Basterds, exemplifies this sense of hyperreality, depicting a fictionalized 1940s world. The script itself took the better part of a decade to be written, developed in numerous variations and structures.“I just come up with what I feel is a neat idea for something, and I’ll put in mind. And I’ll let it incubate for years,” describes Tarantino of this process. “When I want to write, I figure out what genre and what style I want to work in. And I just kind of flip through the old backlog to see which idea’s time has come.” Prior to its release, his method of describing Inglourious Basterds was as a spaghetti western with WWII iconography.

Staying true to his own style, the film reflects traditional hallmarks of his work, including witty dialogue, stylized violence, and irreverent humor.With his advanced knowledge of cinema, Tarantino continues his trend of glorifying and deconstructing genres, as he has with the blaxploitation film (Jackie Brown), the 1970s grindhouse film (Deathproof), and now with combat movies and 1940s film noir.“You’ve got to make a movie about something, and I’m a film guy, so I think in terms of genres,” says Tarantino. “So you get a good idea, and it just moves forward and then usually by the time you’re finished, it doesn’t resemble anything of what might have been the inspiration. It’s simply the spark that starts the fire.”

Beginning Inspirations

The film that sparked that fire this time was the 1978 film Quel Maledetto Treno Blindato, by director Enzo Castellari. The film was released in the United States under the name The Inglorious Bastards. In the 70s, this was seen by some as a Dirty Dozen knock-off, as it debuted almost a decade later than other macaroni combat films. Initially, Tarantino’s film was going to have more in common with the Castellari film, focusing on a men-on-a mission theme. Over time, this changed, and other stories evolved along with the Basterds’ escapades.

At one point, Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds was going to be a twelve-part mini-series, extending the full length of the war. Eventually, Tarantino decided he wanted to create his own mini-masterpiece before the decade ran out, so the film was shortened down to five chapters. He had by then developed the idea of Goebbels as a studio head, and became intrigued by the prospect of focusing on Third Reich cinema through the premiere of a film. He remembers, “When I came up with the idea to deal with the filmmaking end of the Third Reich and the German film industry, I thought, ‘Wow that’s never really been done before.’ So I got really excited by it.” However, to maintain a tribute to the original inspiration, both director Enzo Castellari and actor Bo Svenson would appear in the Tarantino film in small cameos.

Tarantino also decided that he wanted the film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, returning to where he had won the Palm D’or in 1994 for Pulp Fiction. This meant going into production immediately upon completion of the script, and assembling an incredible cast in quick secession. The film was shot in Berlin, or rather just outside at the Babelsberg Studio, and in Paris.

The film is unique in the sense that rather than having various cultures portrayed though English, the film is representative of a multitude of languages. Also, on a number of occasions, the film pays mention to the Germans’ ability to distinguish accents. “I only cast actors who could speak English with their native accents,” insists Tarantino. “The Germans have accents, the French are French, and the English are English. During the war, your understanding of German, whether you were a French citizen or you were in a concentration camp, meant the difference between life and death. In Hollywood movies, Germans often have English accents, and I can’t go for that contrivance. The proper accent could be the difference between success and failure.” Interestingly, this effort towards linguistic accuracy is the one true effort towards realism that is made.

The first two chapters of the film act in homage to spaghetti westerns and macaroni combat films of the 1960s and 70s, introducing a number of the films characters in a contained setting. The first chapter, titled Once Upon a Time in Nazi-Occupied France, has many elements in common with Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (C’era una volt ail West) from 1968. When comparing images from Tarantino’s film, it is evident that he has borrowed Leone’s mise-en-scène in terms of color palette and staging.

The first two chapters of the film act in homage to spaghetti westerns and macaroni combat films of the 1960s and 70s, introducing a number of the films characters in a contained setting. The first chapter, titled Once Upon a Time in Nazi-Occupied France, has many elements in common with Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (C’era una volt ail West) from 1968. When comparing images from Tarantino’s film, it is evident that he has borrowed Leone’s mise-en-scène in terms of color palette and staging.

Explaining this first reference, Tarantino reminisced, “When I decided to become a director, it just came on TV, Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. It was like a book on how to direct, a film so well designed. I watched to see how characters entered the frame and exited the frame.” The opening of Tarantino’s film is also heavily laced with music by Ennio Morriconne, who famously provided the soundtrack for a number of Leone’s films. Both of these films also share thematic qualities, in that they both involve the massacre of a family with a sole survivor, depicting a brutal world where life is cheap, and one could die (as Nazi-occupied France indeed was).

In the second chapter, when the Basterds are introduced, it feels like a flashback to Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen. In this 1960s film, twelve convicted murderers are recruited to lead a mass assassination mission of German soldiers. The Basterds are recruited for a similar mission, except they are Jewish soldiers (with the exceptions of Til Schweiger’s Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz and Brad Pitt’s Lt. Aldo Raine). Once again, mise-en-scène is borrowed from a genre film, as the scene where the Basterds are introduced is very similar visually to when the prisoners are introduced.

In the second chapter, when the Basterds are introduced, it feels like a flashback to Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen. In this 1960s film, twelve convicted murderers are recruited to lead a mass assassination mission of German soldiers. The Basterds are recruited for a similar mission, except they are Jewish soldiers (with the exceptions of Til Schweiger’s Sgt. Hugo Stiglitz and Brad Pitt’s Lt. Aldo Raine). Once again, mise-en-scène is borrowed from a genre film, as the scene where the Basterds are introduced is very similar visually to when the prisoners are introduced.

Lt. Aldo Raine (played by Brad Pitt), the leader of the Basterds, has a number of characteristics in common with the filmmaker Tarantino, the main ones being that he is from Tennessee and is part Native American. Aldo is also one of the only characters that is unable to be anyone other than himself, as his horrible attempt at an Italian accent would reveal. Perhaps this is also how Tarantino views himself.

Lt. Aldo Raine (played by Brad Pitt), the leader of the Basterds, has a number of characteristics in common with the filmmaker Tarantino, the main ones being that he is from Tennessee and is part Native American. Aldo is also one of the only characters that is unable to be anyone other than himself, as his horrible attempt at an Italian accent would reveal. Perhaps this is also how Tarantino views himself.

This connection might be the reason for one of the film’s more interesting twists on the combat film theme; the either Basterds scalp or mark their victims. “One of the things that’s interesting to me is equating the Jews in this case with the Indian in a Western,” explains Tarantino. “Maybe it’s not nothing that I’m 25 percent Cherokee Indian. If I go do a movie of Jewish American fighting back in World War II, then I equate them with the other race that I am, and I use the Indian battle plan, their methods, to attack the Nazis.”

The first two chapters of the movie are based off of action and adventure genres, but the film itself doesn’t become its own adventure movie until the final three chapters. The final three chapters of the film pose a great interest in the realm of German film studies, both for its cinematic references and for its depiction of the German film industry under the German Third Reich. The first of which being a seeming obsession with the filmmaker G.W. Pabst.

G.W. Pabst and Piz Palu

Georg Wilhelm Pabst was an Austrian-born director, whose career spanned for the first half of the twentieth century, making both silent and sound films. While over the course of his career he would attempt a number of different styles and genres, many of his films during the 1920s focused on the women in German society, and the plights they faced. The Nazis were not fans of the Weimar decadence infused in these earlier films, further leading him to switch styles later on. Pabst is mentioned in print and in dialog several times throughout Tarantino’s film; outside the cinema, the briefing of Operation Kino, and in the tavern scene. He is the one filmmaker that receives this much attention throughout the film. For this reason, a brief overview of his major Weimar films and as well as his references in Inglourious Basterds is warranted.

Among Pabst’s early films was The Love of Jeanne Ney from 1922, which was based on a novel by Ilya Ehrenberg. The story begins in the Russian Crimea during the Bolshevik revolution, when Jeanne, a young French woman, falls in love with a young Bolshevik. The role of the Bolsheviks may have drawn the attention of Pabst as he had interest in Marxism, and it is highly unlikely that he had informed the studio of their role in the story. Pabst wanted an even more political theme, but the studio forced him towards the stolen diamond subplot. When the Red Army takes over the town, there are a lot of night street shots, which became a recurring theme in his films of that decade.

Then, in 1925 he directed The Joyless Street, which explored the impact of economic crisis on society. It combined American melodrama with German expressionism, telling to separate dramas. One follows Greta Garbo’s character, who is from a middleclass that is suffering economically, but she maintains her virtue, and receives a happy ending. The other follows Asta Nielsen’s character, who comes from a poor family, and resorts to prostitution and murder, eventually suffering for her sins. Shortly after its release, the film came to exist in many different versions, due both to indiscriminate cuts, and to interventions by censors.

In the following years, Pabst made a number of films with American actress Louise Brooks, including Die Büchse der Pandora and Diary of a Lost Girl, both made in 1929. Both of these films dealt with a young, naïve girl, unaware of her abilities to seduce men, and how desires eventually lead her to become fallen. These silent films helped to build Pabst a strong reputation as a filmmaker.

The film Inglourious Basterds first mentions Pabst in the scene outside the cinema, when Shoshanna is changing the marquee on a ladder. The marquee reads in French: “German Night Leni Riefernstahl in Pabst’s White Hell of Piz Palu,” which the camera passes over several times, offering the viewer multiple opportunities to read it. The White Hell of Piz Palu (Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü) was also made in 1929, and it marked the collaboration between directors Arnold Fanck and G.W. Pabst, working in a mountain genre known as a bergfilm. In her memoirs, Riefenstahl (who acted in a number of these mountain films) describes how this collaboration took place: “I met G.W. Pabst, a filmmaker whom I greatly admired and whose films I had seen several times. We had an instant rapport and it became my great desire to appear in one of his pictures. Suddenly I had a rather crazy idea. If I could talk Sokal [her producer] and Fanck [her director] into allowing Pabst to direct the acting scenes of their film while Fanck shot the outdoor and sport sequences, the combination would be fabulous.”

The film Inglourious Basterds first mentions Pabst in the scene outside the cinema, when Shoshanna is changing the marquee on a ladder. The marquee reads in French: “German Night Leni Riefernstahl in Pabst’s White Hell of Piz Palu,” which the camera passes over several times, offering the viewer multiple opportunities to read it. The White Hell of Piz Palu (Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü) was also made in 1929, and it marked the collaboration between directors Arnold Fanck and G.W. Pabst, working in a mountain genre known as a bergfilm. In her memoirs, Riefenstahl (who acted in a number of these mountain films) describes how this collaboration took place: “I met G.W. Pabst, a filmmaker whom I greatly admired and whose films I had seen several times. We had an instant rapport and it became my great desire to appear in one of his pictures. Suddenly I had a rather crazy idea. If I could talk Sokal [her producer] and Fanck [her director] into allowing Pabst to direct the acting scenes of their film while Fanck shot the outdoor and sport sequences, the combination would be fabulous.”

These films were difficult to make, as cast and crew literally had to climb mountains and brave the severe conditions. In subtext, these were sometimes viewed as “master-race” films, as they would show a group of Aryans conquering the elements. This mountain climbing theme (revisiting Pabst’s Piz Palu) is referenced later on when Aldo invents cover story for Bridget’s leg being in a cast: “The doggie doc’s gonna dig that slug outta your gam. Then he’s gonna wrap it up in a cast, and you gotta good how I broke my leg mountain climbing story. That’s German, ain’t it? Y’all like climbin mountains, don’tch?”

These films were difficult to make, as cast and crew literally had to climb mountains and brave the severe conditions. In subtext, these were sometimes viewed as “master-race” films, as they would show a group of Aryans conquering the elements. This mountain climbing theme (revisiting Pabst’s Piz Palu) is referenced later on when Aldo invents cover story for Bridget’s leg being in a cast: “The doggie doc’s gonna dig that slug outta your gam. Then he’s gonna wrap it up in a cast, and you gotta good how I broke my leg mountain climbing story. That’s German, ain’t it? Y’all like climbin mountains, don’tch?”

While it was not included in the final film, the script includes the following voiceover from the narrator: “To operate a cinema in Paris during the occupation, one had two choices. Either you could show new German propaganda films, produced under the watchful eye of Joseph Goebbels. Or… you could have a German night in your weekly schedule, and show allowed German classic films.” The narrator played a larger role in the script, than in the final film, often explaining and educating, such as he is in this scene. Having knowledge of this information does explain why Shoshanna is having a German night at her cinema. It is inferred that she is not thrilled about it, and she states that she doesn’t have a choice, but there is no indication that this scene is mandated by regulation.

When Shoshanna affirms that she is the one who selects the German films, Zoller commends her choice, stating that he loves Riefernstahl mountain films, especially Piz Palu. When he notes how nice it is to find a fellow admirer of Riefernstahl, Shoshanna replies very coldly that she does not “admire” Riefernstahl (perhaps in reference to Riefenstahl’s propaganda films). When Zoller suggests that she does in fact admire the director Pabst, as she chose to include his name on the marquee, she simply replies, “I’m French. We respect directors in our country.” It’s hard to say whether she is merely reflecting on French culture here, or taking a jab at German culture. Zoller replies back about she apparently even respects German directors. This is his attempt to show that even in her eyes, not all German’s are bad. In another time and place, perhaps these two cinema lovers could have had great discussions about filmmakers, but the Nazi uniform creates a barrier Shoshanna in unwilling to penetrate.

The next scene in which Pabst is mentioned at length is when Lieutenant Archie Hicox (played by Michael Fassbender) is briefed on Operation Kino. In this scene, General Fenech, briefs Hicox as Winston Churchill (played by Rod Taylor) observes. Hicox describes his occupation before the war, being a film critic, writing for the publications “Films and Filmmakers” and “Flickers Bi-Monthly” (both fictional titles). He also is a published author, the first of his books titled; “Art of the Eyes, The Heart, and The Mind: A Study of German Cinema in the Twenties”. The second of his books is titled; “Twenty-Four Frame Da Vinci”, which he describes as a subtextual film criticism study of the work of G.W. Pabst. The 24 frames per second rate became the standard for sound motion pictures in the mid-1920s, and the Da Vinci aspect of the title can infer that Tarantino views Pabst as a master artist, crafting what goes into his frames like a canvas.

The next scene in which Pabst is mentioned at length is when Lieutenant Archie Hicox (played by Michael Fassbender) is briefed on Operation Kino. In this scene, General Fenech, briefs Hicox as Winston Churchill (played by Rod Taylor) observes. Hicox describes his occupation before the war, being a film critic, writing for the publications “Films and Filmmakers” and “Flickers Bi-Monthly” (both fictional titles). He also is a published author, the first of his books titled; “Art of the Eyes, The Heart, and The Mind: A Study of German Cinema in the Twenties”. The second of his books is titled; “Twenty-Four Frame Da Vinci”, which he describes as a subtextual film criticism study of the work of G.W. Pabst. The 24 frames per second rate became the standard for sound motion pictures in the mid-1920s, and the Da Vinci aspect of the title can infer that Tarantino views Pabst as a master artist, crafting what goes into his frames like a canvas.

Pabst is emphasized in one last scene, in the La Louisiane tavern. When Major Hellstrom of the Gestapo reveals himself, he interrogates Hicox on his peculiar German accent. Hicox claims to be from a small village near Piz Palu (which would infer he’s from a German-speaking region of Switzerland). He claims that his family was featured in Pabst’s film when it was shot there, within the skiing torch scene. He claims that Pabst gave his handsome brother a close-up. For the time being, Hellstrom accepts this story. Major Hellstrom then engages Bridget and the Basterds in a game of Hedbanz. The card that ends up on Bridget’s forehead reads “G.W. Pabst” which means it was written by Hicox. Since he has already been described as an expert on Pabst, it does make sense as to why Hicox would reference his name so often, but this constant name recurrence happens often enough that it would only take place in a Tarantino-like reality.

Many of Pabst’s 1920s films dealt with desires and manipulation, where circumstances are often more dangerous than they seem. Perhaps it is this notion of appearances being deceiving that drew Tarantino to reference him so often. In Inglourious Basterds, almost all of the characters deal with the consequences to pretending to be something they are not. Shoshanna is forced to conceal her identity, and in doing so is forced into socializing with the very people who murdered her family. Zoller is a war hero who is hustled into becoming a puppet for Nazi propaganda, even though watching his exploits on screen is difficult for him. Hicox portrays himself as a German soldier, which causes him to be killed. Interestingly, the people who don’t (or are unable to) assume another identity, such as Lt. Aldo Raine and Col. Hans Landa, are among the few survivors of the film. This is not unlike the Pabst street film, when the heroine who retained her integrity has her moment of redemption.

Many of Pabst’s 1920s films dealt with desires and manipulation, where circumstances are often more dangerous than they seem. Perhaps it is this notion of appearances being deceiving that drew Tarantino to reference him so often. In Inglourious Basterds, almost all of the characters deal with the consequences to pretending to be something they are not. Shoshanna is forced to conceal her identity, and in doing so is forced into socializing with the very people who murdered her family. Zoller is a war hero who is hustled into becoming a puppet for Nazi propaganda, even though watching his exploits on screen is difficult for him. Hicox portrays himself as a German soldier, which causes him to be killed. Interestingly, the people who don’t (or are unable to) assume another identity, such as Lt. Aldo Raine and Col. Hans Landa, are among the few survivors of the film. This is not unlike the Pabst street film, when the heroine who retained her integrity has her moment of redemption.

References to the German Film Industry

Throughout his film, Tarantino makes constant references to films and events that took place during Nazi control of the German film industry, demonstrating its far-reaching control. In the previously mentioned scene where Zoller meets Shoshanna, Zoller asks what will be showing at the cinema the following week. Shoshanna replies a Max Linder festival. Zoller also gives kudos to Linder and Chaplin. Max Linder was the star of such early silent films as Max reprend sa Liberté from 1912, was of Jewish descent, although it has been reported that Joseph Goebbels was a fan of him.

Charlie Chaplin was also known for his silent films, but he also made a number of sound films including The Great Dictator in 1940. It is interesting that the character Zoller compliments Chaplin as an artist, in a scene that takes place a year after this 1940 satire, which pokes fun at the Nazis, but perhaps it is because Hitler enjoyed this film, as it is reported that he saw it twice. Daniel Brühl, who plays the part of Zoller, placed this Tarantino film in the tradition of Chaplin’s Great Dictator, noting, “If a comedy is intelligent and has depth, it’s a very legitimate way to talk about Fascism in Nazi Germany, which was also a big show- and if you think about it, very ridiculous.”

Another interesting scene is when Zoller finds Shoshanna in the French Bistro, which is located in the 18th Arrondissement, with characteristic Parisian streets. Just prior to when Zoller appears, a fake billboard can be seen out the window, advertising the film Der Schuerz Bitterer Tränen, starring Zarah Leander and Bridget von Hammersmark. Specifically, Leander’s face is visible. This fake film title might be a reference to the R.W. Fassbinder film Die Bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant from 1972. Zarah Leander is included, as she was a famous UFA actress of this time, appearing in films such as La Habanera, directed byDouglas Sirk. This film was a typical Ufa melodrama film of the time, staring Zarah Leander, who many viewed as Garbo’s replacement. It involved anti-American sentiments, as well as promoting the superiority of Aryans. Leander envisioned herself a singer, and is featured later on in a song played during the restaurant scene. Von Hammersmark is a character that is introduced in the next chapter.

Another interesting scene is when Zoller finds Shoshanna in the French Bistro, which is located in the 18th Arrondissement, with characteristic Parisian streets. Just prior to when Zoller appears, a fake billboard can be seen out the window, advertising the film Der Schuerz Bitterer Tränen, starring Zarah Leander and Bridget von Hammersmark. Specifically, Leander’s face is visible. This fake film title might be a reference to the R.W. Fassbinder film Die Bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant from 1972. Zarah Leander is included, as she was a famous UFA actress of this time, appearing in films such as La Habanera, directed byDouglas Sirk. This film was a typical Ufa melodrama film of the time, staring Zarah Leander, who many viewed as Garbo’s replacement. It involved anti-American sentiments, as well as promoting the superiority of Aryans. Leander envisioned herself a singer, and is featured later on in a song played during the restaurant scene. Von Hammersmark is a character that is introduced in the next chapter.

As the scene continues, Zoller reveals to Shoshanna that he is a famous war hero, and has just starred in a propaganda film telling his story at the request of Joseph Goebbels. In this time, Goebbels had worked to establish a star system in the German film industry that in his eyes rivaled the Hollywood system. Zoller has become a star under this system. In this conversation, Zoller refers to Goebbels as “Joseph”, revealing closeness between the budding celebrity and the propaganda mogul. This also is a warning sign to Shoshanna, as she also refers to Goebbels as “Joseph” right before she walks out on Zoller.

As the scene continues, Zoller reveals to Shoshanna that he is a famous war hero, and has just starred in a propaganda film telling his story at the request of Joseph Goebbels. In this time, Goebbels had worked to establish a star system in the German film industry that in his eyes rivaled the Hollywood system. Zoller has become a star under this system. In this conversation, Zoller refers to Goebbels as “Joseph”, revealing closeness between the budding celebrity and the propaganda mogul. This also is a warning sign to Shoshanna, as she also refers to Goebbels as “Joseph” right before she walks out on Zoller.

When Shoshanna asks what he has been doing in Paris, Zoller replies: “I’ve been doing publicity, having my picture taken with different German luminaries, visiting troops, that sort of thing. Goebbels wants the film to premiere in Paris, so I’ve been helping them in the planning. Joseph is very keen on this film. He’s telling anybody who will listen, when ‘Nation’s Pride’ is released, I’ll be the German Van Johnson.” This is very similar to how celebrities as studios talk and act today when promoting a film or star. Tarantino was very careful when crafting dialogue about the film industry.

Shoshanna later meets Goebbels in a restaurant, where he inquiries about her venue. Just prior to the restaurant, Shoshanna is forcefully picked up by the Gestapo will changing her cinema’s marquee to advertise Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Corbeau It is highly unlikely this film would have screened in Nazi occupied France, as shortly after its release, it was put on trial for being “anti-French.” It was made with Nazi financing, which is interesting because it deals with paranoia around anonymous letters that are stirring up havoc. This rings suspiciously close to the letters German depended upon receiving the informed them of the whereabouts of Jews. For a period of time, Clouzot was banned from directing films in France as a reaction to this film. The placement of this film is an example of Tarantino’s intertextuality, as something that could only exist in his version of occupied France.

Joseph Goebbels, the Third Reich’s Minister of Propaganda (played by Sylvester Groth) is finally introduced in the restaurant scene. Tarantino does not portray him as a monster, but rather how we would view a studio head, which in a sense was something he acted as. “I loved the idea of not just portraying Goebbels as the minister of evil or the architect of evil but truly as his job as studio head of over 800 movies,” describes Tarantino. “He had control and power and sign off ability on every single movie that was made in Germany. And really just playing up his role as studio boss, with his protégé.” Goebbels realized early on that film media was a powerful influence for the masses. He would use this media to promote the Nazi image, while also providing an escape and peace of mind for the theater-going public. He wanted the people to be entertained, and to be able to take their minds off the war. Of the 800 films he oversaw, some were anti-Semitic, but the majority were comedies and musicals.

Joseph Goebbels, the Third Reich’s Minister of Propaganda (played by Sylvester Groth) is finally introduced in the restaurant scene. Tarantino does not portray him as a monster, but rather how we would view a studio head, which in a sense was something he acted as. “I loved the idea of not just portraying Goebbels as the minister of evil or the architect of evil but truly as his job as studio head of over 800 movies,” describes Tarantino. “He had control and power and sign off ability on every single movie that was made in Germany. And really just playing up his role as studio boss, with his protégé.” Goebbels realized early on that film media was a powerful influence for the masses. He would use this media to promote the Nazi image, while also providing an escape and peace of mind for the theater-going public. He wanted the people to be entertained, and to be able to take their minds off the war. Of the 800 films he oversaw, some were anti-Semitic, but the majority were comedies and musicals.

During the restaurant scene, the song “Davon geht die Welt nicht unter”, from the movie Die große Liebe, performed by UFA actress Zarah Leander, can be heard in the background. Die große Liebe (The Great Love) was a German propaganda drama film about the love between a fighter pilot and a singer. It was one of the most commercially successful films of the Third Reich. Tarantino noted her significance by saying, “The thing that is very interesting about [Leander] is the way Bridget von Hammersmark is in the movie- where she’s this big German movie star, but she’s actually working for England- there’s rumors that Zarah Leander was doing the same thing, except for the Soviet Union.”

As the scene progresses, Zoller convinces Goebbels to move the location of film premiere, and Goebbels often gives in to his wishes. This is an interesting demonstration of star power, as the master is compelled by his protégé. After defending why the venue should be changed, Goebbels replies, “I see your public speaking has improved. It appears I’ve created a monster. A strangely persuasive monster. When the war is over, politics awaits.” Zoller as a star is also so used to being recognized, that he is a bit speechless when Shoshanna doesn’t react after he introduces himself the first time they meet.

In a segment of this scene that didn’t make it into the final cut of the film, Goebbels’s inquiries about which German films Shoshanna has, so that he may preview a film in her theater that night. When Shoshanna replies that she only has older German classics as her German audience is older with nostalgia for an earlier time, inferring that she does not have any of Goebbels’s films, he angry replies “That’s nonsense fraulein. Us Germans are looking forward, not backwards. That era of German cinema is dead. The German cinema I create, will not only be thee cinema of Europe. But the world’s only alternative to the degenerate Jewish influence of Hollywood.”

Zoller tries to support Shoshanna, saying that in addition to owning a theater, she is also a film critic. Goebbels replies angrily back that it is too bad for her that he has banned film criticism. Indeed, film criticism in its known state had been banned in 1936. It continued to exist under the name “film contemplation” which adhered to strict guidelines issues by the Ministry of Propaganda. Zoller saves the conversation by suggesting they view Lucky Kids (Glückskinder), which is portrayed as being one of Goebbels’s favorite productions. This film starring Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch, was produced by Ufa. Unlike the stars’ previous musical concoctions, this film took place in New York City (or a reasonable facsimile constructed on the UFA back lot, so it was a NY where they were all speaking German, which was undoubtedly humorous to Tarantino). To save Ann Garden (Harvey) from going to jail, reporter Gil Taylor (Fritsch) pretends to be married to her. This film was modeled after Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night from 1934.

Following their screening of Lucky Kids, Goebbels talks about sprucing up the lobby with nudes from the Louve. In the script, he also mentions taking a chandelier from Versailles, to hang from the auditorium roof. Following this statement, we would have seen a montage of these things being taken, and the theater lobby being decorated with Nazi iconography. Instead, the film version has replaced this scene ending with Goebbels asking what Shoshanna thought of Lucky Kids. When she replies that she liked Lilian Harvey, Goebbels practically spits, demanding that her name never be mentioned in his presence Lilian Harvey had been the most popular star of German musical comedy. She eventually fled the country after she helped Jens Keith, a famous Jewish choreographer, escape to Switzerland, and the Nazi regime withdrew her German citizenship in 1943.

Following their screening of Lucky Kids, Goebbels talks about sprucing up the lobby with nudes from the Louve. In the script, he also mentions taking a chandelier from Versailles, to hang from the auditorium roof. Following this statement, we would have seen a montage of these things being taken, and the theater lobby being decorated with Nazi iconography. Instead, the film version has replaced this scene ending with Goebbels asking what Shoshanna thought of Lucky Kids. When she replies that she liked Lilian Harvey, Goebbels practically spits, demanding that her name never be mentioned in his presence Lilian Harvey had been the most popular star of German musical comedy. She eventually fled the country after she helped Jens Keith, a famous Jewish choreographer, escape to Switzerland, and the Nazi regime withdrew her German citizenship in 1943.

In the previously mentioned scene when Hicox is briefed on Operation Kino, Fenech inquires about Hicox’s knowledge of Nazi cinema. When Fenech first asks if Hicox is familiar with German cinema under the Third Reich, Hicox responds with, “Yes. Obviously I haven’t seen any of the films made in the last three years, but I am familiar with it.” The years described are 1941-1944; his statement infers that these films were not available for viewing perhaps. Fenech then asks him to describe Ufa under Goebbel’s control. To this, Hicox responds, “Goebbels considers the films he’s making to be the beginning of a new era in German cinema. An alternative to what he considers the Jewish German intellectual cinema of the twenties. And the Jewish controlled dogma of Hollywood.”

Churchill asks how successful Goebbels has been in comparison to Louis B. Mayer(producer, creator of the “star system” within MGM, probably mentioned as Goebbels had created his own star system). Hicox responds that Goebbels has indeed been successful, noting an increased film attendance in Germany, but arguing he is more comparable to David O. Selznick (producer of Gone with the Wind of which Goebbels was a fan, and created his own version in the form of Kolberg).

General Fenech is described in the script as a George Sanders type. Sanders acted in a number of anti-Nazi propaganda films at the time, including Confessions of a Nazi Spy directed by Anatole Litvak. This film was the first blatantly anti-Nazi film produced by a major Hollywood studio prior to World War II, and is considered an American propaganda film There was also a large supporting German cast, some of whom had left German after the rise of Hitler (including Martin Kosleck as Joseph Goebbels). This film was banned in Germany, and other countries that were allied with or controlled by the Nazi party. Tarantino described the motivation behind this reference in saying:

I was very influenced by Hollywood propaganda movies made during World War II. Most were made by directors living in Hollywood because the Nazis had taken over their countries… Almost all these movies, by the way, starred George Sanders. I wasn’t taking anything from them stylistically, but what struck me about those movies was that they were made during the war, when the Nazis were still a threat, and these filmmakers probably had had personal experiences with the Nazis, or were worried to death about their families in Europe. Yet these movies are entertaining, they’re funny, there’s humor in them… They’re allowed to be thrilling adventures.

Character Bridget von Hammersmark as a UFA actress, is introduced to us in the scene within the “La Louisiane” tavern. In the tavern scene where we meet Bridget, “Ich wollt ich wär ein Huhn” a song from the movie Glückskinder (Lucky Kids) plays in the background. The film’s stars, Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch, performed this song. There is an interesting parallel here between actresses who betrayal the Nazi party.

Character Bridget von Hammersmark as a UFA actress, is introduced to us in the scene within the “La Louisiane” tavern. In the tavern scene where we meet Bridget, “Ich wollt ich wär ein Huhn” a song from the movie Glückskinder (Lucky Kids) plays in the background. The film’s stars, Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch, performed this song. There is an interesting parallel here between actresses who betrayal the Nazi party.

As the tavern scene was lengthy, some of the dialogue discussing Operation Kino was trimmed from the final film. In the script, Bridget described to Hicox the role he was going to play at the premiere: “You’ll be going as Ernst Schuller. You’ll say you’re an associate producer on Riefenstahl’s “Tiefland”. It’s the one German production not under Goebbels’s control, and Leni wouldn’t be caught dead at a Goebbels film affair.” At some point, Goebbels had tried to court Leni, but she rejected him, and began reporting directly to Hitler. In her memoir, Riefenstahl described the moment that she refused Goebbels:

Goebbels lost control. ‘You must be my mistress, I need you- without you my life is a torment! I’ve been in love with you for such a long time!’ He actually knelt down in front of me and began to sob… it was too much for me and I ordered him to leave my apartment immediately… The future Minister of Propaganda never forgave me for that humiliation.

Whether or not this confrontation between Riefenstahl and Goebbels happened as she claimed, it is well documented that there was a great deal of friction between the two. It’s also worth noting that Tiefland was Hitler’s favorite opera, and some considered Riefenstahl’s adaptation to be a final declaration of love and a farewell. It is interesting to note that the tension in this scene mounts to a Mexican standoff, which has become a common theme in Tarantino films, although this is the first time it is recognized by name.

In the opening scene of Ch.5, Shoshanna stands by a window in contemplation; her window reflection is encased by a Nazi flag and a Bridget von Hammersmark film poster on a nearby building. This is her night against the Nazis and Ufa. The film poster is for a movie titled Fräulein Doktor. This may be referring to the 1933 project that Leni Riefenstahl had been hoping to star in, but had been cancelled due to censorship of its spy-theme content, or it may be referring to the 1937 French drama film Mademoiselle Docteur (Street of Shadows) that was directed by G.W. Pabst. Both of this project focus on the legend of Elsbeth Schragmüller, who was a German spy during World War I.

In the opening scene of Ch.5, Shoshanna stands by a window in contemplation; her window reflection is encased by a Nazi flag and a Bridget von Hammersmark film poster on a nearby building. This is her night against the Nazis and Ufa. The film poster is for a movie titled Fräulein Doktor. This may be referring to the 1933 project that Leni Riefenstahl had been hoping to star in, but had been cancelled due to censorship of its spy-theme content, or it may be referring to the 1937 French drama film Mademoiselle Docteur (Street of Shadows) that was directed by G.W. Pabst. Both of this project focus on the legend of Elsbeth Schragmüller, who was a German spy during World War I.

A David Bowie song plays, building up anticipation- idea of taking a song from somewhere, and turning it into something else. Tarantino, in discussing music, describes, “Part of my process when I’m making a movie is to just dive into my record collection. What I’m looking for is the rhythm of the movie or the beat of the movie… I’m finding pieces, and that keeps inspiring me to make the movie.” In this same sequence, we then see her splicing her film with a reel from Nation’s Pride. It is interesting how this aspect of film exhibition has been included.

At the premiere of Nation’s Pride, we see Emil Jannings as a guest. Jannings was a Swiss actor, and was the first actor to win the Academy Award for Best Actor. In 1930, he starred in The Blue Angel alongside Marlene Dietrich, filming English and German versions at the same time. It was a film about seduction, and a fallen man who loses himself in his desires, taking place in pre-WWII Weimar. It was the first major German sound film (hence why it was filmed in two languages, so not to lose the international audience). Jannings later starred in a number of Nazi propaganda films.

In 1941, Goebbels named Jannings “Artist of the State,” which the film makes mention of for a brief moment with Goebbels, Zoller, and Jannings. Goebbels shows Zoller the ring Jannings had received for the honor, hinting that after the premiere they may have a new candidate with Zoller. His career abruptly ended with the fall of the Nazi party. One of Jannings most well known roles was in The Last Laugh were he portrayed an aging doorman who is forced to retire. In giving up his coat he sheds his identity, which is devastating to him. In a different twist, Col. Landa is hoping to give up his uniform once the war and shed his Nazi identity so that he may live in peace, and is devastated when Aldo prevents him from doing so.

Also at the premiere, both Hermann Göring and Martin Bormann are pointed out. Hermann Göring was a leading member of the Nazi Party, and was the last commander of the Richthofen squadron. He was also Hitler’s designated successor. Martin Bormann was also a prominent member of the Nazi Party, and was Hitler’s private secretary. Having these men present at the premiere is important, as they are among the only individual who could have replaced Hitler and kept fighting. There presence ties in with Tarantino’s “all rotten eggs in one basket.”

In a characteristic moment, Goebbels cries upon hearing Hitler praise his movie, as he is undoubtedly beaming with pride. Tarantino explain his motivations for this, in saying “If Hitler says that this is the greatest movie you’ve ever done, I can see Goebbels getting choked up. When Harvey Weinstein does that, I get a tear in my eye.” This is just one more example of how Goebbels is portrayed similar to a modern movie mogul.

In one of the final scenes, Landa begins to negotiate a deal with Aldo, discussing the value of his participation with Operation Kino. Aldo states that with or without Landa, the bombs in the theater will go off. To this Landa replies: “I have no doubt, and yes, some Germans will die, and yes, it will ruin the evening, and yes, Goebbels will be very very very mad at you for what you have done to his big night. But you won’t get Hitler, you won’t get Goebbels, you won’t get Gering, and you won’t get Bormann. And you need all four to end the war.” (pause) “But if I don’t pick up that phone, right there, you may very well get all four. And if you get all four, you end the war… tonight.”

Leni Riefenstahl and Nazi Propaganda Films

Leni Riefenstahl began her career as an actress in bergfilms, and then went on to become a filmmaker. Henri Richard Sokal, her Piz Palu producer and former lover described Riefenstahl as: “People who are obsessed by themselves, by their urge for self-realization and self mission, like Riefenstahl, are interested in the whole world. They are interested in men only as a tool which has to serve this self-realization. They are playing it in a virtuoso manner. This explains Riefenstahl’s later relationships with Nazi rulers.” She would later try to claim that she was forced into helping the Nazis against her will, but there is a great deal of evidence against this. She was only interested in power, money, and her own career, and Hitler was able to grant her all of these things.

Leni Riefenstahl began her career as an actress in bergfilms, and then went on to become a filmmaker. Henri Richard Sokal, her Piz Palu producer and former lover described Riefenstahl as: “People who are obsessed by themselves, by their urge for self-realization and self mission, like Riefenstahl, are interested in the whole world. They are interested in men only as a tool which has to serve this self-realization. They are playing it in a virtuoso manner. This explains Riefenstahl’s later relationships with Nazi rulers.” She would later try to claim that she was forced into helping the Nazis against her will, but there is a great deal of evidence against this. She was only interested in power, money, and her own career, and Hitler was able to grant her all of these things.

He most famous propaganda film was Triumph of the Will(Triumph des Willens) from 1935. The film title comes from the Nürnberg Party rally of 1934. According to her memoir, when she expressed fear to Hitler that she was unfamiliar with the subject matter, he supposedly replied: “That’s an advantage. Then you’ll only see the essentials. I don’t want a boring Party rally film; I don’t want newsreel shots. I want an artistic visual document. The Party people don’t understand this. Your Blue Light proved that you can do it.”

With Hitler acting essentially as an executive producer, money and access to the event were unlimited to Riefenstahl. He also granted her extremely pompous premieres to exhibit her film. The style of this film separated it from traditional documentaries, incredible artistic sense. This explains why Shoshanna gives such a dark reply when Zoller compliments Riefenstahl as an actress.

She did another, shorter film about the 1935 rally, continuing to demonstrate Germany as a military power, titled Tag der Freiheit: Unsere Wehrmacht (Day of Freedom: Our Armed Forces). Due to the power of these films in terms of Nazi propaganda, similar to Emil Jannings, Riefenstahl’s career was effectively ended with the fall of the Nazis. When asked about her Nazi sympathies in one of her final interviews, Riefenstahl replied, “I apologize for ever being born… but not for my movies.”

Nation’s Pride, the fake propaganda shown in the movie, created by director Eli Roth, who plays the Bear Jew. The more intimate scenes of Zoller feel like a propaganda film, especially when a carved swastika motivates him to keep fighting. However, the actual fighting scenes feel more like a combat film, emphasized by the appearance of Bo Svenson (star of original Inglorious Bastards) who plays a small part. Perhaps instead of comparing this film to German propaganda films, a better film to compare it is the American film To Hell and Back from 1955, which is based on the story of American war hero Audie Murphy. Audie Murphy (like Zoller) portrayed himself in this retelling of his story, and the film was met with commercial and critical success.

Nation’s Pride, the fake propaganda shown in the movie, created by director Eli Roth, who plays the Bear Jew. The more intimate scenes of Zoller feel like a propaganda film, especially when a carved swastika motivates him to keep fighting. However, the actual fighting scenes feel more like a combat film, emphasized by the appearance of Bo Svenson (star of original Inglorious Bastards) who plays a small part. Perhaps instead of comparing this film to German propaganda films, a better film to compare it is the American film To Hell and Back from 1955, which is based on the story of American war hero Audie Murphy. Audie Murphy (like Zoller) portrayed himself in this retelling of his story, and the film was met with commercial and critical success.

During the 4th chapter of the film, there is a scene in which The Führer informs Goebbels that he will be attending the premiere: “I’ve been rethinking my position in regards to your Paris premiere of ‘Nation’s Pride’. As the weeks have gone on, and the Americans are on the beach, I do find myself thinking more and more about this Private Zoller. This boy has done something tremendous for us. And I’m beginning to think my participation in this event could be meaningful.” Hitler’s hesitation in attending the premiere prior to this moment might be attributed to the fact that during the war, he began to see cinema as frivolous, and attending premieres as a dereliction of duty.

During the 4th chapter of the film, there is a scene in which The Führer informs Goebbels that he will be attending the premiere: “I’ve been rethinking my position in regards to your Paris premiere of ‘Nation’s Pride’. As the weeks have gone on, and the Americans are on the beach, I do find myself thinking more and more about this Private Zoller. This boy has done something tremendous for us. And I’m beginning to think my participation in this event could be meaningful.” Hitler’s hesitation in attending the premiere prior to this moment might be attributed to the fact that during the war, he began to see cinema as frivolous, and attending premieres as a dereliction of duty.

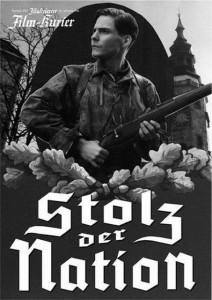

Posters for the film can be seen scattered throughout the lobby at the premiere. In all of the poster depictions of Zoller, he has the appearance of looking heroic and compassionate. This was typical of posters for propaganda posters, as the comparison of Zoller’s poster and a poster of a film from the time both involve their heroes glancing upward and to the side, in a position that is very noble and strong Even Shoshanna gets wrapped up in Zoller’s hero persona, causing her a moments pause after shooting him, and then returning to watch him on screen.

However, Zoller differs from his onscreen persona, and returns fire on Shoshanna in this Romeo and Juliet shootout. Perhaps it goes to show that movies are only dangerous when they are confused with reality.

Final Thoughts

While it feels historically based, Inglourious Basterds is entirely fictional. It’s as if Tarantino took all of the cinematic facts he knew of the time period, and wove his own version of history. While it is easy to recognize the finale takes historical liberties, one should realize this world was fictionalized from the very first chapter. In a sense, the fact that the different chapters allude to different subgenres, demonstrates how what we perceive as cinematic “reality” looks different depending on what genre style it was created in, or even what country it was created in.

One may look at the exploding theater and note that cinema saves the world by destroying itself. However this is narrow view of this cinematic world. Rather, think of it as two teams, one of which is comprised of cinephiles including a theater owner, a black projectionist, a German actress, and a film critic. The other team is an American band of soldiers based out of a 70s combat film. Together, these two teams bring down the Third Reich in its moment of celebration, in a moment where cinema is heroic and capable of ending a war. Nitrate film even acts as the gasoline to the fire.

One may look at the exploding theater and note that cinema saves the world by destroying itself. However this is narrow view of this cinematic world. Rather, think of it as two teams, one of which is comprised of cinephiles including a theater owner, a black projectionist, a German actress, and a film critic. The other team is an American band of soldiers based out of a 70s combat film. Together, these two teams bring down the Third Reich in its moment of celebration, in a moment where cinema is heroic and capable of ending a war. Nitrate film even acts as the gasoline to the fire.

David Wasco, the production designer, noted that while many old photographs and documents were used to reproduce the period, about ninety percent of what they produced was based on film references, referring to the portrayed time as, “a Quentin period world.” In responding to whether audiences would understand his references, Tarantino responded:

I actually believe that when it comes to stuff like that, you should aim over the audience’s head and let them reach out for it. If they have any interest in it, maybe they will now know who G.W. Pabst is now and maybe they’ll investigate it. Actually, when I was a kid, they did that in children’s art all the time, just to give you an example. Maybe at this age, I would know who Baron Von Richthofen was. [But] I knew who he was when I was five because they put him on Snoopy. Because Snoopy fought him all the time. And they weren’t thinking, ‘Hey little kids aren’t going to know who Baron Von Richthofen is. Nope, we’re going to teach them.’

Tarantino uses one of his trademark camera angles to end the movie; a point of view shot where we see a victim’s attackers. In Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, and Kill Bill, these are done as a trunk shot, where a victim is revealed in the trunk of a car. In Deathproof this shot was incorporated in the form of two characters looking under the hood at a doomed engine. In Inglourious Basterds this angle in used twice ), always in the moments after Aldo has carved a swastika into a Nazi soldiers forehead. After this fate is bestowed to Landa, Aldo (channeling Tarantino) looks directly into the camera and proclaims, “I think this just might be my masterpiece.” It is very clear that Tarantino is pleased with the hyperreal world he has created.

Note: There were many sources utilized to write this article. If you would like a list of them, please feel free to contact us.