A mainstay in French for almost 40 years, Jacques Audiard frequently chronicles criminals and convicts (or ex-criminals/ex-convicts) trying to either navigate a seedy underbelly or readjust to civilian life. He broke through to American audiences with his 2009 prison drama A Prophet, about an Algerian youth forced to negotiate between rival subcultures, before winning the Palme d’Or in 2015 for Dheepan, which follows a former Tamil Tiger trying to carve out a little bit of peace in Paris. His latest film, The Sisters Brothers, superficially scans as a departure from his previous work; it’s not only his first English-language film, but it’s also a period Western to boot. Yet, The Sisters Brothers neatly fits into Audiard’s established thematic mode: two hitmen whose latest mission inevitably forces them to envision a future without violence and crime.

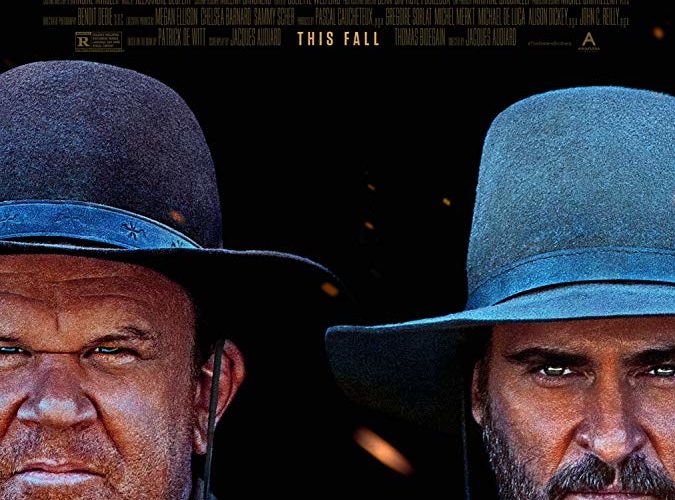

Adapted from Patrick deWitt’s novel by Audiard and his screenwriting partner Thomas Bidegain, The Sisters Brothers’ core story compels on its own accord. Set in 1851 from the Pacific Northwest down to California, John C. Reilly and Joaquin Phoenix play the eponymous Brothers who are tasked to retrieve a special formula for finding gold from renowned chemist/prospector Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed). Though their criminal associate, John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), has been assigned to stalk and hold Warm until the Brothers arrive, he eventually shirks his duty after being swayed by the chemist’s ability and rhetoric. Now, the Brothers must find both Morris and Warm before their boss, the mysterious Commodore (Rutger Hauer), raises any suspicion.

The Brothers’ episodic journey necessarily facilitates many encounters with various townsfolk who are frighteningly aware of their violent reputation. Reilly’s Eli Sisters chafes against their disreputable career, secretly longing for any semblance of normalcy, while Phoenix’s Charlie Sisters harbors great enthusiasm for the hitman lifestyle, thrilled to be doing something at which he excels. Reilly’s sensitivity contrasts well with Phoenix’s aggro-boisterousness, and the two actors (both members of large families incidentally) easily fall into sibling chemistry. Audiard parallels Eli and Charlie with Morris and Warm, who subscribe to complementary personalities, but he neither forces the comparison nor draws belabored connections between the pairs of men. Instead, Audiard mostly expresses a restrained curiosity regarding their similarities. His strong facility with actors, coupled with the four individually compelling performances, imbues the film with affection but retains a sense of mystery. The figures in The Sisters Brothers feel lived in, but fundamentally unknowable.

Though certain setpieces indicate Audiard’s skill as a stylist—an opening shootout lit only by gunfire, an extended digression at a brothel that ends in bloodshed, a fruitful search for gold stymied by greed and impatience—The Sisters Brothers really comes to life when he focuses on the details in the margins. Audiard and Bidegain, and presumably deWitt, have a vested interest in depicting American life as lived in the mid-19th century, especially the ways in which new technology alter frontier life. Reilly is rarely better in the film than when he hesitantly uses tooth powder to brush his teeth for the first time, or when he marvels at an indoor toilet in a fancy San Francisco hotel. These new luxuries disrupt the Brothers’ ritualistic lifestyle, which mostly involves a set routine of riding, sleeping, drinking and killing, and yet they represent the future. The film juxtaposes these rapid advances with the relatively slow medical progress of the time; in most cases, sickness or infection usually spelled death. Audiard permeates The Sisters Brothers with a knowing sense of melancholy, illustrating that the proverbial times are a-changing even if it has to drag certain figures kicking and screaming into the modern world.

However, The Sisters Brothers undoubtedly feels lacking in some regards. Audiard doesn’t really invest enough interest in his film’s primary conflict—Eli’s desire for domesticity clashing with Charlie’s profound love for the criminal life—which is trite and tired despite Reilly and Phoenix’s typically expert performances. Moreover, despite attempts to studiously avoid clichés, the film’s crucial anticlimactic moments fall into flat, predictable territory. Individual scenes absorb, and the film lives and dies by its performances, but the macro problem seems to be that The Sisters Brothers can’t quite transcend its imitation atmosphere. Audiard and his cinematographer Benoît Debie nail the Western aesthetic, but neither can grasp the feeling. This wouldn’t be an issue if Audiard had postmodern aspirations, but The Sisters Brothers wants to be in conversation with the genre while still retaining a sincere, unwinking approach. This tactic engenders a bloodless quality in the film, a sort of technical remove that allows passive admiration of the craft while precluding active emotional investment. The Sisters Brothers exhibits emotional depth, but can’t figure out how to translate it, as if a crucial element has been missing all along.

The Sisters Brothers premiered at Venice 2018 and opens on September 21.