It doesn’t take long to explain a film like Hopper/Welles in relative detail. In 1970, Dennis Hopper took a break from editing The Last Movie and flew to Los Angeles to be interviewed by Orson Welles. Welles was working on what would later––much, much later––become The Other Side of the Wind. During a boozy candlelit dinner party, surrounded by a small group of friends, Welles’ cameras rolled on Hopper for a little over two hours as they discussed politics and filmmaking. This is exactly what we see.

The timing of the interview could hardly be more enticing. By 1970 Welles (who was only turning 55) had already begun to slip into the notorious talk show appearances and novelty roles that would define the late part of his career (for perspective, at the same age Scorsese had only just made Kundun). Hot on the epoch-shifting success of Easy Rider, Hopper was at the peak of his career, but he was also just about to release The Last Movie, a commercial bomb that meant the studios wouldn’t touch him––it would be 9 years before he went behind the camera again. That lingering hubris is palpable and if there was anyone who knew a thing or two about studio priorities––not to mention the pitfalls of early successes––it was the man he was talking to.

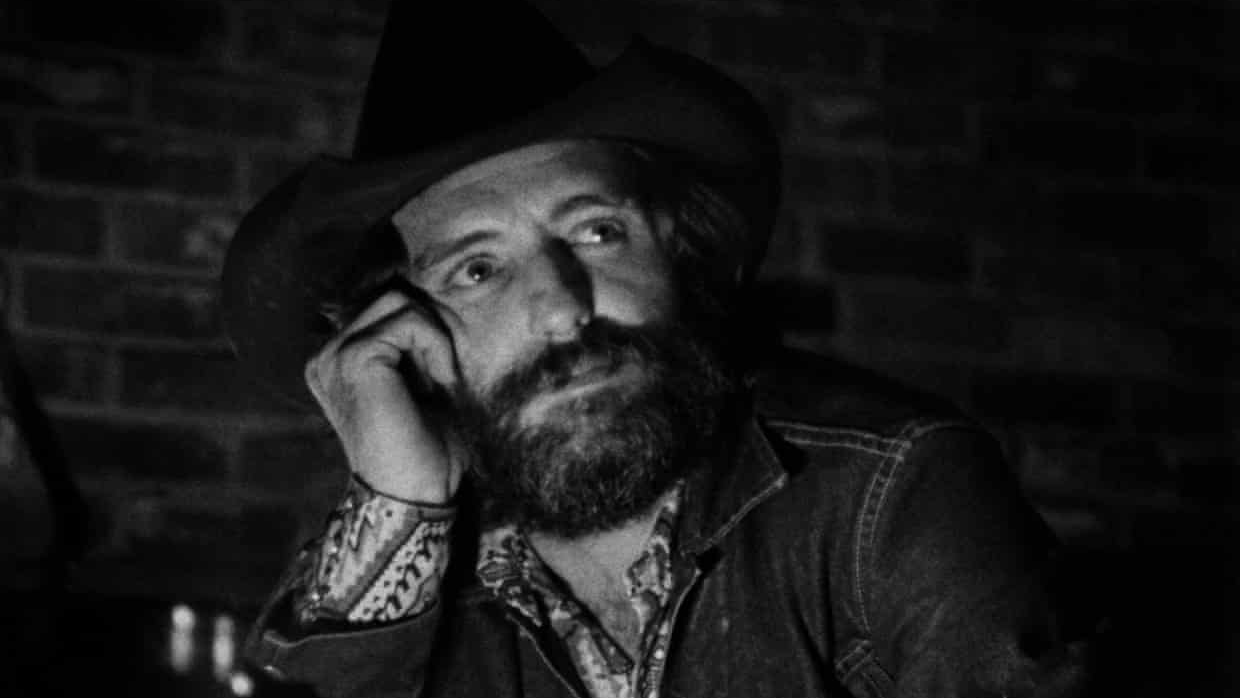

Yet Hopper/Welles is a decidedly unusual thing. Welles and cinematographer Gary Graver, who shot The Other Side of the Wind, are still credited as director and cinematographer respectively. Bob Murawski, who was brought in to edit Wind in 2017, does the required chopping and changing. But it’s clear the intended form hasn’t changed much from what was shot in 1970, making it a completely different kind of film to Kent Jones’ Hitchcock/Truffaut, from which Hopper/Welles appears to take its name. That is still a tantalizing proposition in many ways––like an untouched echo from the past––but it will no doubt be one for the purists. There are moments anyone could enjoy (Welles not knowing who Bob Dylan is in 1970 for one) but in strictly visual terms our eyes are transfixed on Hopper in a cowboy hat, chain-smoking, and sipping G and Ts.

The conversation is at its very best in the opening exchanges when we are offered a glimpse of Hopper’s cinephilia, discussing Antonioni and Resnais. Unfortunately, Welles seems more concerned with his politics. The public’s reaction to Easy Rider provides an entry point for a lengthy and quite resonant conversation on Hopper’s position in popular culture––held up as a hero by counterculturists, a role he is reluctant to take––and the different interpretations of the film’s ending by conservatives and liberals. Welles seems determined to make the younger man reveal a strong political leaning, but Hopper (who by that point had become a target for the FBI) is evasive. The conversation begins to go in circles.

That clash of personalities remains the key draw, even as this gnawing repetitiveness sets in. Both men were responsible for debut films that changed the industry yet they seem reluctant to admit any similarities. A begrudging respect is there, but so is a deep-rooted generational gap and an ideological one, too. Welles found out about the price of being an outsider early on. Perhaps the most interesting thing in Hopper/Welles is that you can’t quite tell if the battle-scarred veteran is looking to wrap an arm around the younger man or is trying to defeat him.

Hopper/Welles premiered at the Venice Film Festival.