A woman sits at the edge of a bed, brushing her hair while a young boy and girl are positioned to her side, sleeping soundly. The camera, stationary, can capture nothing but the shapes of three bodies, segments of a comforter, and a wall whose minimal qualities of design would give the stronger impression of a small film set than actual room. This sequence proceeds for a few minutes; no dialogue is spoken and none of these people are identified, yet one can understand, on an almost-instinctual level, that it’s a mother figure, either worn down by her children or sitting in blissful relaxation. Not that we need read too greatly into this bare situation: an explication of circumstance is not necessary, nor is the opportunity for an explication of circumstance necessarily provided. Taken both in its entirety and viewed within proper context, the image is as much a proposition as an introduction, demanding our acclimation to a peculiar tenor of temporal cinematic geography — no room for personal compromise included.

Five shots and upwards of ten minutes later, the threads begin to reveal themselves: the timeless quality of nature and the aggravatingly “now” suffocation of a metropolitan landscape are juxtaposed, and, while initially giving the impression of counterpoints, delicately interlock to unexpected degrees. We’d struggle to properly identify any of the figures made central in these shots, but patterns and associations are forming; from this point forward, our basic trust must be imparted from viewer to film. But, this notwithstanding, to assess Stray Dogs with nothing but a written recollection feels regressive, perhaps to a dangerous degree. Even the most thorough textual illustration of Taiwanese helmer Tsai Ming-liang’s newest feature — by his own account, the final of a career that’s lasted more than twenty years — would fail to capture what makes it such a formally monumental, intellectually brutalizing achievement, and by any reasonable stretch among the finest works released in 2013.

While Tsai drives forward with a plot which, in relative terms, could be traced in a “point A to point B” manner, Stray Dogs’ path towards the realization of both its narrative and emotional significance come, to a seemingly willing extent, at the price of complete and total coherence. It’s not merely the film’s slipperiness in establishing a clear-cut identity for its several protagonists, but trying to find an exact incentive behind each scene’s placement in the greater structure; strands may be returned to, in certain respects, but their mysteries are quietly, almost playfully danced around for much of the picture — during which time, regardless of our expectations and desires, other developments proceed in a compact, orderly fashion. Only through time and consideration is a larger tapestry revealed as connections spring up, Tsai placing carefully delineated visual associations and signifiers of memory until, slowly, the carefully delineated structure brings us back to the point in question.

While this sense of structure would most immediately and most obviously bring to mind 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Tsai’s rhythms of composition and cutting have a more significant kinship with the lure-and-strike sensation one finds themselves overcome with when viewing Jeanne Dielman. It’s to the film’s credit that Stray Dogs would follow Akerman‘s proclivities for pacing and articulation, over the span of its 138 minutes avoiding all-too-possible formal didacticism through a disregard of whatever comfort may have been heretofore established by way of minor structural “rules”; just as its successive threads habituate an attentive viewer to the artificial glow of conformity-fueled modern environments, such small luxuries are discombobulated by the harsh, unforgiving plunge into states of poverty or, worse yet, the shelter-bereft living of a natural world.

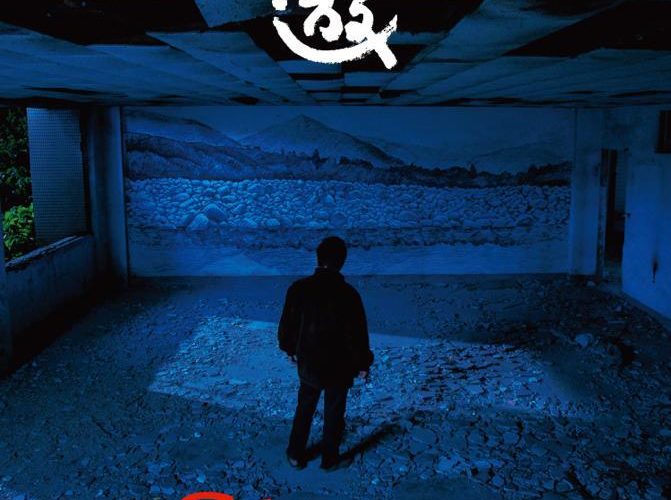

Each cut opens a new world, and from each cut, into each extended vision, the intensely sedate qualities of Tsai’s formal construction seek an equal ground with the silently stated emotion of what’s manifested onscreen: the degradation of using a public bathroom for sanitary purposes; the mystery in a woman’s observation of a painting, this double-layered act of seeing at once reversed and expanded, to great extent, in the film’s near-silent climax; or, even, the desperation in eating a head of cabbage. These are portions which could be assessed from a relatively distanced stance — the more basic aspects of framing, camera distance, lighting, and performance prove impeccable — but the power they carry is so dependent upon nearly every preceding moment — nearly every preceding shot — that, separated, the experience of viewing each scene would be roughly akin to examining an individual, fine-tuned machine part: gratifying, but without a larger purpose.

To wit, occasionally discernible excess-marred passages — the picture’s final two shots last somewhere in the vicinity of twenty minutes; as powerful as a single, simple gesture may prove when stasis has been elongated like so, discomfort shifts from palpably intentional to overly palpable — need be essentially overlooked when processed as part of a whole, their utilization only emboldening the mastery of medium Tsai has been exerting from one incident to the next. If this, truly, is his send-off, Stray Dogs is a finish for the history books.

Stray Dogs played at TIFF and will, soon, be seen at NYFF, though no domestic distributor has yet been established. One can see the trailer here and click below for all of our festival coverage.