As the arthouse cinema market continues to regain its footing, the list of what may be considered an overlooked film could be quite vast, depending on one’s metrics. For our yearly feature highlighting the 50 most overlooked films––arriving before our overall top 50 films––we’ve sought to dig deep to find the gems that deserved more attention upon their initial release and have mostly been left out of year-end conversations. Hopefully, with many widely available on a variety of streaming platforms, they will begin to find an expanded audience.

Sadly, many documentaries would qualify for this list, but we stuck strictly to narrative efforts; one can instead read our rundown of the top docs here. While they aren’t included on this list, we also hope a number of 2022 qualifying films find an audience when they get a proper release next year, including Saint Omer, One Fine Morning, and Return to Seoul.

Check out the list below, as presented in alphabetical order.

The African Desperate (Martine Syms)

Early into Martine Syms’ The African Desperate, MFA finalist Palace (Diamond Stingily) sits for her last exam in an upstate New York art school tucked deep in the woods. It’s the end of a three-year voyage, the kind of moment that should trigger swaths of pride and relief. But Palace, a Black student in an exceedingly white college, is frustrated, tired, on the verge of a breakdown. Her art has already shown at the Venice Biennale, a feat her all-Caucasian examiners don’t really know how to respond to. (Did she earn a spot because of talent, or…?) Even after they christen her a Master of Fine Arts, the mix of animosity and envy lingers acridly in the room. “There are lots of female artists your age and race making the same stuff you’re doing,” a professor chides her over drinks, “how are you going to differentiate yourself?” – Leonardo G. (full review)

All My Friends Hate Me (Andrew Gaynord)

Pete (Tom Stourton) hasn’t seen his university mates in years. Ten years to be exact. It happens. Life happens. We reach adulthood, mature, and set goals for ourselves that the people who were closest to us during that formidable period simply cannot follow—their own ambitions lie upon different forks in the road. So resentment shouldn’t factor in. Nor should jealousy. Yet Pete can’t help wondering about both. A little voice in the back of his head wonders if a decade was too long to pretend things could pick up where they left off. Would their very posh upbringing think he abandoned them to work with refugees? Do they think he thinks he’s better than them for doing it? What if he thinks that? – Jared M. (full review)

Ali & Ava (Clio Barnard)

It’s so rare to find a romance between two middle-aged characters wherein the main conflict is just baggage of past relationships and past hurt. Ali & Ava is, given Clio Barnard’s three previous bleak features, surprisingly sweet. Though sticking with her usual Yorkshire setting, there’s so much love in how she depicts the Bradford community in which Ali and Ava live. Claire Rushbrook and Adeel Akhtar’s chemistry is wonderful. – Orla S.

Anaïs in Love (Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet)

The seasons have changed––spring is here, summer is on the way, and no film out right now better exudes the aura of love in the sunshine than Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet’s Anaïs in Love. Broke, behind on her rent, and considering breaking up with her boyfriend, thirtysomething Anaïs (Anaïs Demoustier) doesn’t quite know what she wants from life. Struggling to complete her thesis, she wanders aimlessly through the film’s first act––a free spirit with no sense of direction but capable of turning heads and drawing the attention of others wherever she goes. She’s like a manic pixie dream girl without the reductive qualities of the trope. Bourgeois-Tacquet creates in her lead an instantly recognizable portrait of a young woman right at that nexus point where not having your shit figured out is starting to look a little bit uncool. – Mitchell B. (full review)

Apollo 10 1⁄2: A Space Age Childhood (Richard Linklater)

It might seem wrong to find a Jack Black-narrated, Richard Linklater-written and -directed Netflix movie on a “most overlooked” list. Lord knows they don’t need the publicity. But—believe it or not—Apollo 10 ½ belongs, the modest minor masterpiece it is. It’s hard to say what exactly stiff-armed audiences about Linklater’s semi-autobiographical, rotoscoped time capsule of a cosmically obsessed Houston, Texas, circa 1969, but it dropped on the father streamer in April and flew under the radar like a dumped mystery-free true-crime doc. From the opening seconds, and without skipping a beat, Black narrates us through the kaleidoscopic swirl of live-action animation in one electric, nostalgic 98-minute scene-setting montage. Imagine Alec Baldwin’s opening narration in The Royal Tenenbaums but…the voiceover never ends. It sounds like an awful idea on paper and probably is for most filmmakers. And that’s what makes the greats great: they aren’t like most other filmmakers. – Luke H.

Apples (Christos Nikou)

Apples is set in a world where digital technology seems not to exist, yet the psychic imprint of the digital age hangs heavy over first-time director Christos Nikou’s sparse absurdist dramedy. In an alternate-universe Greece, people are falling victim to a pandemic of sudden-onset Memento syndrome: total, crippling amnesia that befalls ordinary adults seemingly at random, necessitating elaborate state-run medical programs for the mnemonically impaired. Of particular concern to such programs are “unclaimed” amnesiacs, patients who fail to be identified by friends or family members and thus become wards of the state, who must be gradually rehabilitated into society and construct new identities from scratch. – Eli F. (full review)

Benediction (Terence Davies)

Time is everything in a Terence Davies film. In Benediction, his biopic about English poet Siegfried Sassoon (Jack Lowden), he eventually covers his subject’s marriage to Hester Gatty (Kate Phillips). There’s a shot of the couple standing still, facing the camera as they pose for a wedding photo (a shot that tends to pop up throughout the director’s filmography). The camera flashes, we see the black-and-white photo, and then a fade transitions us to the future, where it rests on their bedside while Hester looks at their newborn child. The sequence is an encapsulation of what Davies does best: observing life with one’s head facing backwards, the cumulative weight of the past bearing down on every moment of the present. – C.J. P. (full review)

Il Buco (Michelangelo Frammartino)

His follow-up to 2010’s Le Quattro Volte, Il Buco director Michelangelo Frammartino falls into that pesky category of filmmakers who don’t work near frequently enough. Il Buco tells two stories set in the mountains of southern Italy in 1661: a cave diving expedition and a portrait of an elderly shepherd slowly dying. The central metaphor connecting the two stories isn’t overly complex, and the beauty here comes from experiencing the rhythms of moving between the green fields above to the darkest of the cave beneath—both quiet in their own majestic ways. Frammartino’s cinema may be one of stillness, but that’s not to discount his mischievous side as well. – Caleb H.

Catch the Fair One (Josef Kubota Wladyka)

Catch the Fair One could’ve been turned into a vehicle for Liam Neeson or Mel Gibson to play white saviors protecting indigenous women from sex traffickers. Casting Kali Reis, a queer woman of Native American and Cape Verdean descent, as its vigilante hero doesn’t automatically make it progressive, but Catch the Fair One works in a brutally determined B-movie vein. The grim vibe cuts hard, reminding us that one woman’s individual actions can only go so far in rectifying systemic violence. – Steve E.

A Chiara (Jonas Carpignano)

Non-professional Swamy Rotolo is Chiara, a confident teenager whose coming of age is kicked off by the discovery that her father is in the mafia. The rest of her family—played by Rotolo’s actual—aren’t so helplessly naïve, and Carpignano deftly tracks familial interactions that move between understanding and frustration. Describing Carpignano’s Calabrian trilogy, as set within the Italian Neorealist, tradition might be accurate, but such a simplistic description sells his work short—this is not derivative imitation. Carpignano has spent a decade living in the southern Italian region building real relationships; the result is a mafia film focused on the human cost, thrilling yet never exploitative. Whether Carpignano decides to stay in Calabria, decamp to another region, or make movies in the U.S., we eagerly await his follow-up. – Caleb H.

Los conductos (Camilo Restrepo)

Succinctly potent like a concentrated shot of a mood-altering substance, Camilo Restrepo’s Los conductos renders a Colombian portrait of a damaged soul reclaiming his humanity amidst widespread bleakness. In a swift 70 minutes, the lugubriously solemn film punctures one’s psyche as it interrogates a society’s moral corrosion that has normalized violence as the lone avenue to salvation for the marginalized. – Carlos A. (full review)

Clara Sola (Nathalie Álvarez Mesén)

Earlier this year, in Goran Stolevski’s You Won’t Be Alone, a young witch becomes enamored with the life of humans. She starts to interact in a world where she is forbidden, giving up her relation to the witch mother keeping her under her control. Throughout that movie there are inklings of discovery, almost like a child first learning to walk and speak, to eventually realizing what love is. If there is a similar dynamic in Nathalie Álvarez Mesén’s Clara Sola, this is also a movie that finds its central character escaping religious suppression and contending with her burgeoning sexuality. It recalls Stolevski’s film in the treatment of “breaking out of the shell” as a sort of “growing up” but grounds itself in cultural tradition rather than historical fantasy. – Soham G. (full review)

Confess, Fletch (Greg Mottola)

Jon Hamm takes up the iconic role of Irwin Fletcher in Greg Mottola’s updated Confess, Fletch, one of the year’s funniest, slightest films. Hamm eases into the role, relaxed and unfazed as the bumbling detective. Mottola’s work is breezy, easy to enjoy without much thought or complication. If the script falters and story becomes convoluted, Hamm picks it up, happy to keep the good times rolling. Finally: a director to utilize his comedic talents. Fletch becomes Hamm and Hamm becomes Fletch, at least for a new generation. – Michael F.

Costa Brava, Lebanon (Mounia Akl)

What can you do when your homeland’s falling apart? The easy answer is stay or leave, but both options carry too much complexity to simply choose and be done. For starters, not everyone has that choice—whether due to finances, family, or myriad other reasons. And those who are able must dig deep within themselves to rationalize why. Do you leave because of greater opportunity? Do you stay because you want to be part of the solution? Or do you find yourself in a sort of purgatory—one foot planted on each side, only to discover your fear of losing out on the benefits of one for the potential of the other has you locked in stasis? That’s where Walid (Saleh Bakri) currently exists. – Jared M. (full review)

Deception (Arnaud Desplechin)

Knowing Philip Roth’s “novel” about an extramarital affair was a barely fictional plaything, Deception starts as story and becomes biography: we witness Roth’s processes, entanglements, nightmares—a literal trial for the crime of misogyny and copy of My Life as a Man emblazoned with his name making exhibit A—and their ruinous effects on his marriage (no mistake the actress so resembles then-wife Claire Bloom). It’s one of the strangest, most enveloping acts of literary-cinematic matrimony I’ve ever seen, in certain keys akin to Paul Schrader’s Mishima but played through Desplechin’s relentless appetite for set-ups, optical effects, production-design eccentricity, and at its beating heart Denis Podalydès and Léa Seydoux’s unlikely union formed by vivid onscreen chemistry. A one-two punch of quiet Cannes premiere and misguided reviews almost left Desplechin’s film perpetually unseen (the first of two times in as many years), making MUBI’s release so much more necessary. – Nick N.

Detective vs. Sleuths (Wai Ka-fai)

Aka Law and Order: Chaos. Longtime Johnnie To collaborator Wai Ka-fai, working solo, expands the police procedural’s possibilities while poking holes in it. Full of shootouts, chase scenes, and explosions across Hong Kong as a deeply troubled cop investigates a serial killer, it’s thoroughly unconcerned with making sense. Tonally unique, it looks over the pain of violence through decades while maintaining a broad irreverence that never tips over into comedy. – Steve E.

Fabian: Going to the Dogs (Dominik Graf)

In the first hour of Dominik Graf’s Fabian: Going to the Dogs, we see the title character running around 1920s Berlin, bumping into eccentric characters at bars and nightclubs while the camera moves and cuts at a whirlwind pace. It’s a time of indulgence and recklessness for Fabian and other young people in Germany, and then he finds himself standing face to face with a young woman in the back of a club. The camera cuts to a rapid-fire montage of both characters together and in love, scenes from later in the film we haven’t gotten to yet. Up to this point, Fabian was living in the present; without warning he begins to see a future, and we get to see it too. – C.J. P.

The Fallout (Megan Park)

Megan Park’s directorial debut The Fallout seemingly came and went. Released early in the year, this school-shooting drama stars Jenna Ortega (who achieved immense fame nearly a year later) in the most impressive performance of a budding career. Ortega conveys the weight of teenagehood in the year 2022, the fear students feel walking through school hallways. Park’s film takes a gentle approach, an understanding of how trauma seeps into a person, especially one burgeoning into an adult. It contains a sense of reality, a non-dramatization of the effect of school shootings, which have become more and more normal over the last decade. It’s an important film in the teen-focused space usually reserved for much lighter fare. – Michael F.

Feast (Tim Leyendekker)

In the mid-2000s several men committed a heinous crime in the Netherlands: they would bring men to their home for sex parties, drug them, and then inject them with their own HIV-infected blood before dumping them on the street. Filmmaker Tim Leyendekker tackles this notorious story in his first feature, Feast, with a unique approach, splitting it into seven parts that deal with the crime in different ways—real documentary interviews, faux-documentary interviews, dramatic recreations among them. The specificity and horror of what happened would be enough for a director to create something more conventional from this true-crime story, but Leyendekker refuses to make a single minute of his film go down easy. Each vignette reframes the incident in a new light, challenges assumptions, and at some points comes close to sympathizing with the perpetrators’ romantic view of what they did. One of the year’s most provocative films, Feast bucks the current inclination to make up viewers’ minds. – C.J. P.

First Love (A.J. Edwards)

Following The Better Angels and Age Out, A.J. Edwards’ third feature, First Love, is both a tender tale of blossoming romance and nuanced depiction of the pride and human frailties that can disrupt a decades-long bond. The writer-director, who got his start working with Terrence Malick on The Tree of Life, The New World, To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song, displays an immense amount of grace in this recession-era portrait of family and romance. Led by Hero Fiennes Tiffin, Diane Kruger, Jeffrey Donovan, and Sydney Park, the film got a quiet release earlier this summer, but certainly deserves to find an audience in coming years. – Jordan R.

Friends and Strangers (James Vaughan)

Rare is the prospect of an Australian comedy. Within, say, two minutes it becomes clear James Vaughn’s feature (his first) must be followed through: images of metropolitan life composed like Heinz Emigholz, willingly stilted performances, vaguely threatening vibe. Progressively the thing grows funnier, its direction harder to guess, structure slightly bewildering yet fully determined. By film’s end Friends and Strangers is plainly fucking hilarious, teetering on the possibility of violent outburst while conveying a wise statement on personal misdirection. I saw this movie nearly two years ago and think about it more than almost any I watched last month; all it took was those two minutes. – Nick N.

Funny Pages (Owen Kline)

In the increasingly sanitized landscape of contemporary American cinema, the unrelenting scuzziness of Funny Pages feels, ironically, like a breath of fresh air. Owen Kline’s coming-of-age comedy, which follows an adolescent New Jerseyite cartoonist’s unsteady attempts to strike out on his own, is a caustic, at times excruciatingly uncomfortable interrogation of creative contradictions: does an upper-class background preclude someone from accessing counterculture? If an artist thinks too much about their art, does it stop being art? Can true genius exist in the mind of a man who habitually beefs with Rite Aid employees? Though the film’s influences––Zwigoff’s Ghost World, Resnais’ I Want to Go Home, the stylings of such seminal underground comix figures as S. Clay Wilson and R. Crumb––are apparent, its overall thrust is deeply personal, the work of a filmmaker with an abiding love for outsider art and keen eye for the absurd. – Cole K.

Gagarine (Fanny Liatard and Jérémy Trouilh)

Named after the famous Soviet astronaut whose last name his apartment complex was bequeathed with in the ’60s, Gagarine follows Yuri, who just wants better for his home and the people he grew up with. Metaphor may be an overused literary tool, but the visual imagery conjured by directors Fanny Liatard and Jeremy Trouilh––through twisting, turning, and contorting the camera from to fashion a dilapidated apartment complex like it a spaceship––makes the film an imaginative and melancholic drama about a changing urban landscape in France and the desperation to escape instability by looking to the sky. – Soham G.

The Girl and the Spider (Ramon and Silvan Zürcher)

Ostensibly the story of a Berlin family preparing for its evening dinner as a cat wanders the apartment, The Strange Little Cat was among the most beguiling films of the early-to-mid 2010s and its more mysterious explorations of everyday family life. With the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival entry The Girl and the Spider, director Ramon Zürcher returns, with brother Silvan Zürcher as co-director. (The latter produced The Strange Little Cat.) Spider is equally captivating––a mesmerizing, uniquely ambiguous study of friendship, rivalry, tension, and memory. It is difficult to remember another recent film that does so much with so little in the way of plot and location. – Chris S. (full review)

Girl Picture (Alli Haapasalo)

While it doesn’t break entirely new ground, Alli Haapasalo’s Sundance winner and Berlinale selection Girl Picture is an energetic, deeply felt coming-of-age film that takes a unique structure. Set across three separate Fridays in Finland, it follows the adventures of three young women facing first love, heartbreak, and reckoning with their next steps in life. As Brianna Zigler said in her review, “Haapasalo’s film is a free-wheeling portrayal of (cis) feminine adolescence in its various complicated, unflattering incarnations: familial pains, burgeoning sexualities, finding balance between work and pleasure, all the while trying to figure out who the fuck you even are. As a girl I intimately know the score and often found Girl Picture warmly reflecting my own experiences.”

Hit the Road (Panah Panahi)

“Where are you taking my child?” The unnerving mystery at the heart of Iranian writer-director Panah Panahi’s (son of legend Jafar Panahi) debut hovers beneath the surface of an otherwise quirky, chaotic, gut-busting family road trip drama. The crew: a tender, worried mom, a loveable oaf of an injured dad, the most adorable 6-year-old little brother, and a near-silent older brother behind the wheel. Exactly what is on everyone’s mind remains hidden in the fog-choked mountainside abyss of their endpoint until the final moments. But it comes out along the way in a steep range of emotion, as our most pressure-cooked feelings often do: a comical, life-ruining conversation about Lance Armstrong, plants nurturing people in the midst of mourning, deep existential uncertainty. Balancing Sorkin-esque, cocaine-quick family dialogue with long, pregnant pauses of anticipatory stillness with unforgettable needle drops (as road trip movies are contractually obligated to have) and everything in between, Panahi oscillates between devastation and glee with poise, proving himself a filmmaker worth looking out for. Sometimes nepotism is a good thing. – Luke H.

Întregalde (Radu Muntean)

In Întregalde, a group of well-meaning young people attempting to deliver aid to a remote region of Transylvania are derailed when their car gets stuck in the mud. Radu Muntean’s film captures that unique sensation of being lost or stranded, as an initially-inconvenient situation spirals into something more dangerous—the dread growing with each hour that help does not arrive. Not quite a horror film, however, it’s making larger points about the futility of middle-class efforts to help the disadvantaged. But like any good socially conscious art, Întregalde also works as an expertly plotted drama-thriller. – Caleb H.

Inu-oh (Masaaki Yuasa)

Director Masaaki Yuasa and screenwriter Akiko Nogi’s adaptation of Hideo Furukawa’s novel The Tale of the Heike: The Inu-oh Chapters finishes with a couple screens of text describing its titular Noh performer’s final years of success, despite his name being all but forgotten in comparison to the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s personal favorite. It’s why these three have brought the story of Inu-oh to life—to ensure his name, and that of his friend Tomona from Dan-no-ura, a blind biwa-playing priest, won’t disappear again. What better way to do so than a 14th-century anachronistic rock opera set during Japan’s Muromachi period, courtesy two cursed men who dare give voice to the voiceless and subsequently free themselves from the chains that society uses to bind them? – Jared M. (full review)

The Last City and The Lobby (Heinz Emigholz)

Canadian novelist and playwright Robertson Davies once compared the continuity of a reader’s relationship to literature to that of architecture transforming in appearance with the rise and fall of the sun: “A truly great book should be read in youth, again in maturity and once more in old age, as a fine building should be seen by morning light, at noon and by moonlight.” Davies’ refrain resounds throughout watching The Last City and The Lobby, the latest films from veteran experimental filmmaker Heinz Emigholz. Although each can be viewed as standalone, their thematic and formal ambitions are best realized as two parts of a larger whole––a concept expressed therein by the films themselves. – Kyle P. (full review)

The Long Walk (Mattie Do)

Modernization and traditional living collide to strong political effect in Mattie Do’s third feature film The Long Walk. Its first few images see both an unidentified flying ship traveling at warp speed and a rusted-up scooter. We see dirt roads and vegetables being sold in plastic bags in a farmer’s market but currency is now paid through a digital microchip in your wrist. “Oh you’re using an old government chip,” the tender tells The Old Man (Yannawoutthi Chanthalangsy). It seems it’s already out-of-date. Things move fast in The Long Walk while others stay relatively the same. – Soham G. (full review)

Madalena (Madiano Marcheti)

Madalena is never just a name in Madalena, Madiano Marcheti’s haunting debut film about the murder of a trans woman set in rural Brazil. For some she’s a source of income and friendship, and for others panic and loss. The film follows a trio of characters whose disparate lives all somehow overlapped with the lifeless person now lying in a vast field of green soy crops. In doing so, Marcheti’s film presents varying reactions to trauma that ripple outward, revealing the subtle nuances of societal intolerance and personal grief. – Glenn H. (full review)

Medusa (Anita Rocha da Silveira)

Writer-director Anita Rocha da Silveira has created an evangelical town of purity in her Brazilian-set sophomore film Medusa. It’s the type of place all Christians wish they could send their children because they know they will be carried into God’s light. The young men form a militia group to honor His will against deviants that dare embrace sin. The young women form a gang in the likeness of their heroine angel, donning white masks to confront and assault the so-called “sluts” and “whores” who dare walk alone at night in search of carnal pleasure. Their violence? All part of God’s plan. Their chastity? A test to prove themselves worthy of pairing off with a like-minded believer to be married and live according to God’s unyielding law. – Jared M. (full review)

Murina (Antoneta Alamat Kusijanovic)

We often forget that exotic locales aren’t an escape for those living here. While co-eds dock ashore for sun, sex, and fun, families merely wake up early to go spearfishing so they have dinner that night. The psychological toll of constantly looking out your window at happy faces while dealing with the futility of teenage living under a domineering father with few (if any) opportunities to leave must be daunting. So when Julija (Gracija Filipovic) exits the water to see her father’s (Leon Lucev’s Ante) rich friend from a past life (Cliff Curtis’ Javi) has arrived, she wonders about the possibilities he brings. Ante and her mother (Danica Curcic’s Nela) hope to sell him land. Julija hopes he’ll save her. – Jared M. (full review)

A New Old Play (Qiu Jiongjiong)

A historically dense yet formally playful exploration of China over a half-century beginning in the 1930s, Qiu Jiongjiong’s first fictional feature A New Old Play may seem daunting on its surface, running nearly three hours and taking place over just a handful of lovingly detailed sets. Once one settles into its theatric rhythms, there is much beauty to behold. Occupying spaces that are humorous and heartbreaking––often in the same breath––we witness a theatre troupe’s journey through a time of immense turmoil. While the play-as-cinema approach results in a certain emotional distance, its unique vision is one worth experiencing. – Jordan R.

A Night of Knowing Nothing (Payal Kapadia)

What starts as an abstract love story through letters recovered from a college in India slowly transforms into a brutal awakening––a flowing, livewire account of student protest and violent retaliation at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehwu University over the past several years. Steeped in an eerie, all-consuming hypnosis, writer-director Payal Kapadia’s debut feature resonates like a veteran experimental work––more like something Godard would’ve made in his 80s than something by a newcomer with three shorts to their name. Under Kapadia’s assured, inventive direction, A Night of Knowing Nothing is a river of revolution, forsaken love, political poetry, fractured memory, collective morality, human-rights atrocities, and existential crises coated in a shimmering black-and-white film grain and set to a blend of narrated docu-fiction too artfully spare and entrancing to interrogate until after it’s suddenly rushed by. Kapadia is able to stretch her avant-garde wings while both entertaining us in form and educating us on the contemporary fight against casteism in India. But perhaps most impressively she’s made the rare documentary that calls the viewer to action with a true, contagious sense of conviction and compassion. – Luke H.

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (Arthur Harari)

Arthur Harari’s Onoda (subtitled 10,000 Nights in the Jungle) tells the true story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier stationed on the island of Lubang in the Philippines circa 1944. When news came of Japan’s surrender he refused to believe it, thus spending the next three decades in seclusion, refusing to leave his post (he finally left in 1974, when his former commanding officer was flown in to relieve him of duties). It’s an extraordinary tale that poses the challenge of conveying its central character’s superhuman levels of devotion and denial, which Harari takes on by going long. With a runtime of more than 160 minutes, Harari takes time to establish and develop the story, opting for a total immersion in the jungle environment and a dedication to realism that makes it hard not to eventually give yourself over to the film with a full level of commitment. Onoda’s ability to sweep viewers up into its detail and realism makes its final act come as a sort of shock—the inevitable ending to this long chapter of Onoda’s life reveals a strong emotional undercurrent that comes seemingly out of nowhere in its moving finale. – C.J. P.

Outside Noise (Ted Fendt)

Ted Fendt’s film is concerned with these times of transition, phases of passage that lead to fleeting ideas of where to live, sleep problems associated with stagnation, and momentary lapses in the concrete nature of life while sitting by a river. It could last five hours and it’s unlikely Fendt would ever give these characters a firm backstory. But it’s a leisurely 61 minutes, never needing to rush towards an incident or conclusion. It’s formless and meandering, incomplete and unassuming—lifelike. – Michael F. (full review)

The Pink Cloud (Iuli Gerbase)

Iuli Gerbase’s The Pink Cloud starts off with a disclaimer: “This film was written in 2017 and shot in 2019. Any resemblance to real life is purely coincidental.” Indeed, it doesn’t take long before the uncanny connections between Gerbase’s film and the real-life COVID-19 pandemic become quite unsettlingly clear, in what feels like the simultaneously most accurate and most dystopic depiction of life during a pandemic (namely, during lockdowns of the first part of 2020). – Brianna Z. (full review)

Please, Baby, Please (Amanda Kramer)

If Rainer Werner Fassbinder had ever decided to take a swing at adapting West Side Story with a dash of John Water’s high camp aesthetic brought in—plus pertinent social commentary—that may be a close summation of Amanda Kramer’s underrated Please Baby Please. Replete with campy aesthetics, striking visuals, and catchy jazz numbers while also being suffused with an exploration of gender roles, Kramer has crafted a picture destined for queer cinema cult status. – Margaret R.

Private Desert (Aly Muritiba)

Writer-director Aly Muritiba said something very interesting about his new film Private Desert in the lead-up to its Venice debut. He spoke about a desire for its success to not simply be of the “preaching to the choir” variety. Rather than hope an artist, who already understands the breadth of love, could find something at the core of his love story, Muritiba wanted to open the hearts of those trapped under the oppressive force of conservatism and traditionalism. This tale of a conflicted policeman discovering his online lover isn’t who he thinks she is possesses the opportunity to connect with those who see themselves in the former, not the latter. And he embraces that possibility. Some audience members have not. – Jared M. (full review)

Public Toilet Africa (Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah)

Impeccably dressed, eyes shielded by sunglasses and arms dangling from the windows of their Nissan pickup, Ama (Briggitte Appiah) and Sadiq (David Klu) breeze through Ghana like twenty-first century cousins of Anta and Mory, the Bonnie and Clyde couple in Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki. They’re the two young people at the heart of Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah’s Public Toilet Africa, a picaresque, irreverent journey where a model seeks revenge for her childhood traumas. Or at least that’s one of the many films tucked inside writer-director Ofosu-Yeboah’s feature debut. Public Toilet Africa is several things—a revenge tale, a road trip, a tale of a city and a remote village; a courtroom drama—and if the ride isn’t always smooth, the end result is a rebellious and oneiric portrait of a country wrestling with the specters of colonialism. – Leonardo G. (full review)

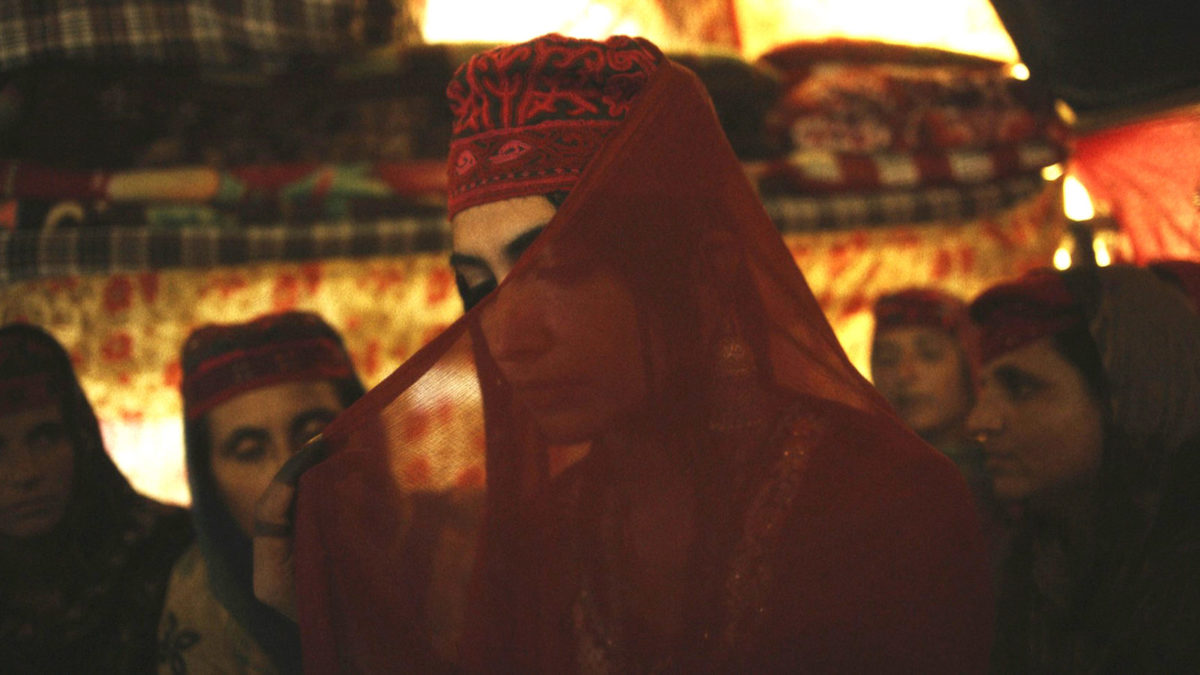

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (Pushpendra Singh)

Northwest India’s Jammu and Kashmir region resides at the center of a longstanding geopolitical stalemate involving neighboring Pakistan. While those tensions are referenced in The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs, they are not the film’s focal point. Instead, paranoia and opportunism have become fully ingrained in the forest area’s mountainous bedrock. Of more importance is why these characters either accept or subvert such societal realities, and how they normalize modes of corruption and gender inequality under the guise of tradition or progress. – Glenn H. (full review)

Saloum (Jean Luc Herbulot)

In 2020, Congolese writer, director, and producer Jean Luc Herbulot partnered with Senegalese producer Pamela Diop to create Lacmé Studios in order to sustainably and autonomously make their own films in Africa. Two years later, they’ve released their first Herbulot-written and -directed project: Saloum––a painstakingly and breathtakingly imagined (costumes, props, sets, locations, et al) thrill ride so light on its feet you won’t believe 84 minutes have passed. To Herbulot’s credit, the film is so unburdened by genre that it’s hard to name one that feels right. A mercilessly evocative blend of old western, crime thriller, supernatural horror, and small village drama grounded in colonialist history and a post-apocalyptic eclecticism, the elements fuse to evoke the surreal sense of the spiritual found in the dreamscape that is the Kingdom of Saloum. – Luke H.

Strawberry Mansion (Albert Birney and Kentucker Audley)

In Strawberry Mansion, co-director Kentucker Audley stars as James Preble, a dream auditor who enters the mind of an elderly woman (Penny Fuller) to tax her dreamscapes. The resulting journey is one of the more ambitious, endlessly-creative low budget movies in quite some time. What stands out the most might be the sense of scale that directors Albert Birney and Audley replicate from the childhood adventure films that inspired the film. Birney and Audley weren’t content to just make their own childhood adventure however, and they add contemporary elements including a subplot featuring Linas Phillips illegally inserting advertising into people’s subconscious. Filled to the brim with ideas and sublime imagery, Strawberry Mansion is proof that budgetary limitations need not limit an artist’s vision. – Caleb H.

The Tale of King Crab (Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis)

A rare and elusive sense of myth is captured in The Tale of King Crab, a story of a 19th-century vagabond who falls in love with the daughter of a local farmer only to run afoul of a prince. (Tough luck.) Later on, astonishingly, he finds himself on the other side of the world. With that kind of spatial and temporal scope, it’s remarkable that Crab is only the first narrative feature from Italian filmmakers Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis, a duo whose output, while ostensibly non-fiction to this point, has often played on the boundary of fable. Small traces of both Black Beast (their 2013 short about a legendary animal) and Il Sonengo (their 2018 feature documentary about a lone hermit) can be located in Crab, a film with all the texture of a folktale—one passed through generations, the facts blurring and embellishments only growing more ethereal with each retelling. – Rory O. (full review)

Taste (Lê Bảo)

Lê Bảo’s Taste is set in Saigon, but for the best part of its 97 minutes, all action is confined to a bunker-like abode where five people meet and hide. The place is dark, unfurnished, and dank; so spectral in its emptiness you’d wonder if the quiet tenants are alive or ghosts. In the stunning chiaroscuro of their unlikely home all motion slows into choreography, characters freeze in a state of protracted wait, and there seems to be only a very blurred distinction between the dreaming and the dead. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Teenage Emotions (Frederic Da)

Watching Frederic Da’s Teenage Emotions can feel like a bit of a shock at first. Shot entirely on iPhones in extreme close-ups, Da films teenagers around a Los Angeles high school in what looks like raw, point-and-shoot footage. In its opening minutes, the shoddy and garish nature of the visuals makes the film look like it could be mistaken for an assignment made by one of its characters. But in no time these perceived flaws turn out to be the film’s greatest assets. On a surface level, Teenage Emotions is an ugly film, but that ugliness helps give it a vitality that makes it one of the most authentic and entertaining portraits of high school in ages. – C.J. P. (full review)

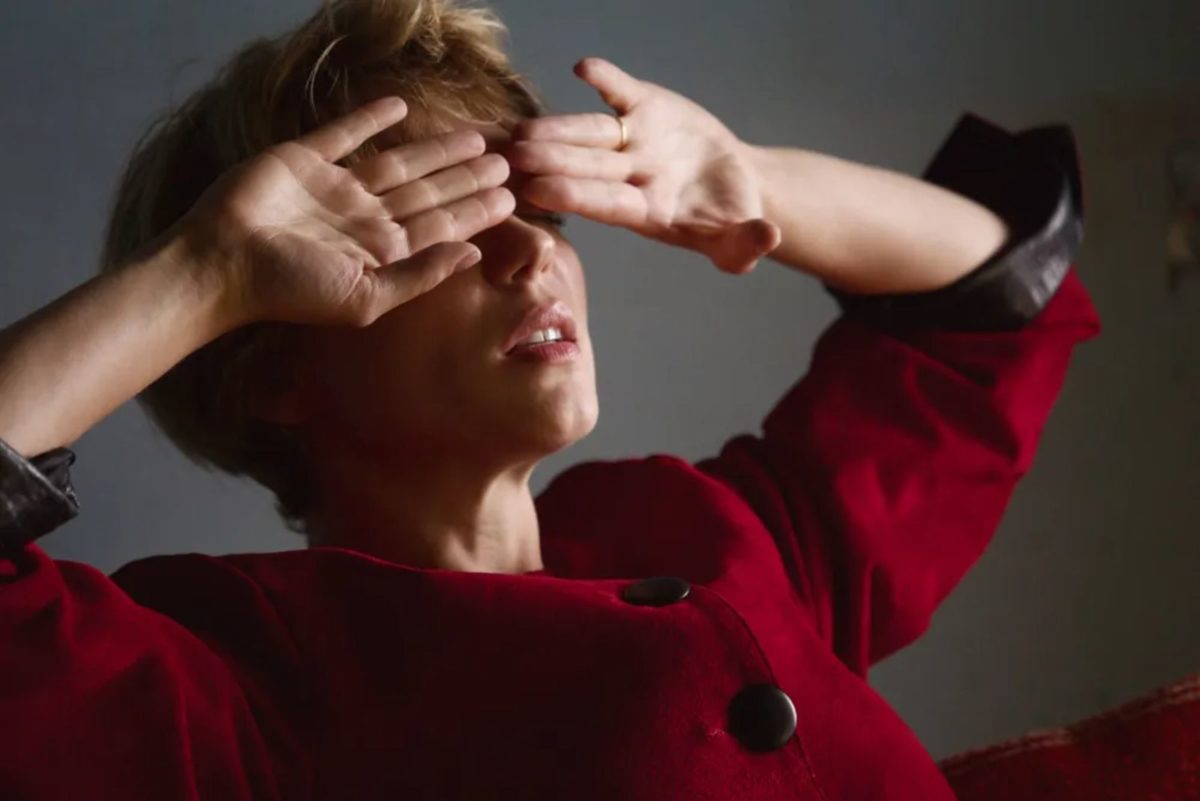

That Kind of Summer (Denis Côté)

A pleasingly old-fashioned belief in therapeutic methods––what you could describe, in a streamlined way, as “the talking cure”––is what drives That Kind of Summer. The idea, sometimes mocked, of sex addiction has been refined here as “hypersexuality,” referring to unrestrained sexual behaviors as well as invasive thoughts of that nature. We are at a therapeutic retreat in the Quebec countryside, attended by three women—Léonie (Larissa Corriveau), Eugénie (Laure Giappiconi) and Geisha (Aude Mathieu)—accompanied by three mediators: Octavia (Anne Ratte-Polle), Samir (Samir Guesmi, late of a few Desplechin films) and Mathilde (Marie-Claude Guérin). The opening remarks from Mathilde, revealed to be pregnant in a deadpan-comic insert shot, are intended to be sincere and reassuring, her language redeemed from the therapy-speak bromides which often spark eye-rolling: “This is not a cure. You are not sick. This is a journey, not a treatment.” – David K. (full review)

Wood and Water (Jonas Bak)

Germany’s mountainous Black Forest region and Hong Kong Island couldn’t be more dissimilar in terms of terrain. Yet, Jonas Bak’s debut film Wood and Water spiritually connects these two epic spaces for a retired church administrator named Anke (played by the filmmaker’s own mother) entering a time of great transition. Not surprisingly, one of the film’s most important dialogue sequences ends with someone noting, “It’s funny how things coincide.” – Glenn H. (full review)

Zero Fucks Given (Emmanuel Marre, Julie Lecoustre)

After breaking out in Blue is the Warmest Color nearly a decade ago, Adèle Exarchopoulos has recently had a string of notable performances with Sibyl, Mandibules, and now last year’s Cannes Critics’ Week selection Zero Fucks Given. In the MUBI release, the actress plays a flight attendant for a lower-tier airline that contends with the soul-sucking monotony of entry-level work. Making for an ideal double feature with Jordan Tetewsky and Joshua Pikovsky’s recent Slamdance winner Hannah Ha Ha, Zero Fucks Given also eloquently explores millennial aimlessness in a capitalistic society that has no room for personal ambitions. – Jordan R.