In a year marked by a recovering box office and distributors experimenting with a wide variety of types of releases, what does an overlooked film constitute? While there are fewer means than in years past to quantify such a metric, there are still plenty of films that didn’t get their due throughout 2021 and deserve more attention in the weeks, months, years to come.

Sadly, many documentaries would qualify for this list, but we stuck strictly to narrative efforts; one can instead read our rundown of the top docs here. Check out the list below, as presented in alphabetical order. A great deal of the below titles are also available to stream, so check out our feature here to catch up.

Anne at 13,000 Ft (Kazik Radwanski)

There’s a neat metaphor established at the outset of Anne at 13,000 ft, with its protagonist’s professional and personal life mirroring the freefall she experiences while skydiving at her friend’s bachelorette party. But with Kazik Radwanski’s direction and Deragh Campbell’s fierce performance, this parallel stretches to the breaking point as Anne deliberately chases the same near-death thrill in her daily life on a path of self-destruction. After a brief but successful festival run in 2019 and early 2020, Radwanski’s film had its release delayed by over a year due to the pandemic, hurting its chances of having more people discover one of Canada’s most exciting new filmmakers. – C.J. P.

Azor (Andreas Fontana)

An almost suffocating air of secrecy permeates Azor, a Swiss-Argentinean coproduction concerning the mutual suspicion and damnable complicity of patrician North Atlantic capitalism and repressive regimes in the postcolonial Global South. The year is 1980, and a private banker from Geneva circulates among the Buenos Aires elite. This is at the height of the Dirty War, though so absolute is the Swiss banker’s discretion—so clean his hands—that the military junta’s crimes against its people feel as suggestively peripheral to the film’s narrative as the word “disappeared” implies. Filmmaker Andreas Fontana’s debut feature is a film of almost Le Carréan subtlety, of oblique plotting, crouching dialogue, and guarded performances masking sinister realpolitik. – Mark A. (full review)

Atlantis (Valentyn Vasyanovych)

In Valentyn Vasyanovych’s post-apocalyptic Atlantis, the sky above Ukraine hangs like a sheet of steel, a uniform mass of clouds bucketing water onto the mud-covered wasteland down below. The year is 2025, and the country has just emerged victorious–if shattered–from a war with Russia. It’s a conflict all too steeped in the decade’s real-life skirmishes between Ukraine and its neighbor to come across as strictly fictional, and that’s the thing that makes Atlantis so disturbing. It’d be tempting to call Vasyanovych’s a dystopia, were it not for that fact that, all through its 108 minutes, everything about it feels almost unbearably vivid–closer to some news report or a post-conflict documentary than any artificial rendition thereof. There are soldiers gingerly plucking mines out of fields, foreign NGOs fretting about the country’s recovery, unidentified corpses exhumed and re-buried, and shell-shocked veterans struggling to find their way back into civilian life. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Boiling Point (Philip Barantini)

More often than not, one-take films struggle to justify their gimmick. Whether shot in one go or utilizing an intensive editing process to appear like so, the technique almost always threatens to overshadow whatever story is at the center rather than emphasizing it. Used correctly, it can prove immersive in the exact same way as a theatrical production—breaking down barriers between performer and audience, who can see their work unfold in real-time. Unfortunately, the impracticality of telling a story this way is usually highlighted via several scenes of actors slowly walking between filming locations. – Alistair R. (full review)

Caveat (Damian Mc Carthy)

An amnesiac takes a job babysitting a young woman in a secluded home over the weekend, and in turn discovers a whole lot of creepy things in Damian Mc Carthy’s directorial debut. Shot on a shoestring budget and completed over several years, Caveat excels as a mood piece, with a sparse setup used as an opportunity to show off its meticulous, unsettling production design (a warped rabbit doll that springs to life whenever it senses an evil presence is one of those images you won’t forget). Caveat came and went earlier this year after getting released on the streaming service Shudder, but hopefully enough people will see it to get Mc Carthy the chance to make another film. – C.J. P.

Charlatan (Agnieszka Holland)

It’s amazing that Agnieszka Holland, a filmmaker who has been doing incredible work for decades now, released one of her best films this year and few people batted an eye. But Charlatan is truly sublime: a period piece set in the 1950s Czech Republic, seen through the eyes of faith healer Jan Mikolásek (Ivan Trojan). It’s a gripping character study about how far humans will go for self preservation under a totalitarian regime. In that sense, it’s a compelling companion piece to Holland’s Europa Europa. – Orla S.

Come True (Anthony Scott Burns)

The darkened screen is almost pitch black before we can begin to discern shapes in the distance. First it’s wooden stakes in the ground at what looks to be a trailhead of sorts. Next it’s a mountain in the distance. Finally we come to a door that swings open as though we’ve been placed inside a videogame merging the puzzle mechanics of Myst with the brooding aesthetic of Hellraiser only to continue moving forward towards a bald figure with back turned—unmoving and foreboding with a mysterious air that can conjure nothing besides dread. And suddenly it’s over with a cut to Sarah (Julia Sarah Stone) awakening from a nightmare, bundled inside a sleeping bag and laying atop a playground slide. The day commences. The images slightly fade. – Jared M. (full review)

Cryptozoo (Dash Shaw)

The current state of American animated cinema is more than a little disappointing; Pixar, Disney, Dreamworks, and more regurgitate the same formula and offer nothing new but a juxtaposition of cartoon designs and hyper-realistic imagery; animation for adults is all too rare. When something like Dash Shaw and Jane Samborski’s Cryptozoo comes along, it’s easy to recognize as one of the most gorgeous works of American animation in ages. – Juan B. (full review)

Detention (John Hsu)

As a subversive poem (according to the Chinese Nationalist Party that ruled Taiwan under martial law during the period known as the White Terror from 1947 until 1987) read by Miss Yin (Cecilia Choi) to the members of her and Mr. Chang’s (Meng-Po Fu) underground high school book club relates: a tree’s roots never ask to be repaid by the fruit that blooms as a result of their effort. It’s a succinctly beautiful metaphor for the education system and its liberal teachers doing all they can to ensure the next generation graduates with a full awareness of the problematic history surrounding them. Rather than facilitate the creation of future oppressors, those like Yin and Chang seek to cultivate free thinkers who will always refuse to blindly accept authoritarianism. That it comes from the cinematic adaptation of a Taiwanese videogame entitled Detention shouldn’t surprise anyone aware of how powerful art can prove regardless of the stigma its medium carries. Director John Hsu and his co-writers Shih-Keng Chien and Lyra Fu looked beyond the scares and atmosphere of this horror property to see the message at its center about the survivor’s guilt that’s all but assured in the aftermath of such a repressive nightmare that saw around 140,000 dissidents imprisoned with almost three percent of that number executed. – Jared M. (full review)

A Dim Valley (Brandon Colvin)

Set during a hot Kentucky summer, Brandon Colvin’s film follows a biology professor (Robert Longstreet) and his two graduate students (Whitmer Thomas & Zach Weintraub) as they collect samples, get stoned, and kill time in the woods until three nymphs show up and change their lives. One of the few truly original films to come out of the US this year, A Dim Valley takes on the deceiving appearance of a lazy hangout movie to reveal much more going on beneath the surface: sexual tension, queer desire, magical realism, and a genuine sense of vulnerability, among other surprises. Despite its relaxed summer vibes, Colvin creates a potent mood where anything can (and does) happen. – C.J. P.

The Disciple (Chaitanya Tamhane)

In The Disciple, a dedicated student of traditional North Indian music must grapple with the nagging feeling that he might not be quite good enough. The film is the latest from Chaitanya Tamhane, an Indian filmmaker who made a big splash in Venice in 2014 when his debut feature Court—a naturalistic film that quietly and comprehensively lampooned the Indian criminal justice system––won the Horizons award for best film. He was 27 at the time, still relatively young, yet some called it a masterpiece. Now at 33, Tamhane has followed it with a story about a person who hopes, perhaps in vain, to achieve such acclaim. We suggest approaching with a degree of caution if such doubts sound eerily familiar. – Rory O. (full review)

The Dry (Robert Connolly)

Aaron Falk (Eric Bana) wasn’t ever planning on coming back. Leaving wasn’t his choice, but at a certain point the present replaces the past. Hearing that his best friend from high school killed his wife and son before turning the gun on himself wasn’t therefore going to change his mind. If anything, knowing that truth and the fact that Luke was gone might have been the final nail as far as never returning at all. But that’s when the card came with a cryptic message more or less blackmailing Aaron into attending the funeral. It was sent by Luke’s father and stated that he knew they lied twenty years ago. What was the lie? We don’t yet know. Whatever it was, though, it worked. Aaron was heading home. – Jared M. (full review)

Eyimofe (This Is My Desire) (Arie and Chuko Esiri)

Home is profoundly where the heartache is in Eyimofe (This Is My Desire), a finely wrought, wistful but mildly unsatisfying debut feature by Nigerian-raised, New York-educated twins Arie and Chuko Esiri. Tracking two resilient Lagos residents, in sequential order, united by one goal––to illegally migrate in search of a better life––the film occasionally feels akin to an immaculately put-together class assignment, over-mindful of the reaction of an end user or assessor, rather than a risky, personality-infused piece of art. – David K. (full review)

Fauna (Nicolás Pereda)

Early in Mexican-Canadian filmmaker Nicolás Pereda’s succinctly effective farce Fauna, Paco (Francisco Barreiro), a thespian with a non-speaking part in the popular show Narcos, is asked to conjure up a performance in the middle of an empty pool hall. His girlfriend’s father wants to see him act on command. Adding to the film’s meta undertones that later turn more noticeable is the fact that Barreirois is in fact part of the Netflix series. – Carlos A. (full review)

The Fever (Maya Da-Rin)

By any conservative approximation, in the week that spanned the moment I left the Locarno screening of Maya Da-Rin’s The Fever and the minute I began writing this piece, an area as vast as 100 million square meters has been wiped away from Brazil’s Amazon basin. Over that seven-day window, President Bolsonaro has rushed to oust scientists unaligned with his regime, the international community promised sanctions against Brazil, and the Twitterverse rallied to the paean #PrayforAmazon, all while a surface as large as a one-and-a-half soccer field continues to disintegrate to flames each and every minute. The Fever, director-cum-visual artist Da-Rin’s first full-length feature project, puts a human face to a statistic that hardly captures the genocide Brazil is suffering. This is not just a wonderfully crafted, superb exercise in filmmaking, a multilayered tale that seesaws between social realism and magic. It is a call to action, an unassuming manifesto hashed in the present tense but reverberating as a plea from a world already past us, a memoir of sorts. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Holler (Nicole Riegel)

You can only hide so many eviction notices underneath the porch flowerpot before a bank official finds and tapes them all onto the front door. This is where we meet Ruth (Jessica Barden) and Blaze Avery (Gus Halper). What choice do they have, though? With their mother (Pamela Adlon’s Rhonda) in jail because of a refusal to go to rehab for a pain pill addiction and family friend Linda (Becky Ann Baker) already over-extending herself to help, these two siblings are waking up at dawn to sell soda cans for pennies at the local scrap heap owned by Hark (Austin Amelio). Blaze works nonstop to keep them from going hungry and Ruth misses so many classes that her high school teachers have given up on even considering college. – Jared M. (full review)

I Blame Society (Gillian Wallace Horvat)

Are the qualities of a successful filmmaker the same as those that make a prolific serial killer? Both certainly demand meticulous planning and precision. In I Blame Society, star-writer-director Gillian Wallace Horvat posits that maybe both roles also require a degree of sociopathy. This hilarious mockumentary features Wallace Horvat (playing a homicidal version of herself) setting out to test a friend’s “compliment” — that she would make a good murderer — by shooting a doc on how to commit the perfect murder. – Orla S. (full review)

Identifying Features (Fernanda Valadez)

Fernanda Valadez’s Identifying Features is without a doubt one of the most visually striking and haunting films of the year. IT follows worried mother Magdalena (Mercedes Hernández) in search of her missing adult son who attempted to cross the border from Mexico to the United States. It’s a perilous journey during which we see how Magdalena is just one of so many desperate people in the same situation, treated as unimportant by the powers that be. – Orla S.

The Inheritance (Ephraim Asili)

History, art, ideology, and love make up the four pillars of Ephraim Asili’s The Inheritance, a thrillingly alive debut feature that resides both inside the square rooms of a West Philadelphia house and outside the boundaries of genre. As its title suggests, to assume the past experiences, lessons, and artistic creations of others can be liberating. But there’s also great personal responsibility to pass on that knowledge in some productive way. – Glenn H. (full review)

Isabella (Matías Piñeiro)

Women from Shakespeare’s oeuvre find themselves reincarnated in modern-day South America through the recent works of Argentine director Matías Piñeiro (Hermia & Helena, The Princess of France, Viola), which operate with non-linear structures concentrated on the intersection between the professional and intimate lives of actresses or aspiring artists. His unassumingly sumptuous new feature Isabella–which channels the central sister-brother dilemma in the British author’s Measure for Measure–examines two women’s unexpressed self-doubt, their aversion to risk, and conflicted career aspirations in an initially puzzling but ultimately rewarding fragmented narrative. – Carlos A. (full review)

The Killing of Two Lovers (Robert Machoian)

Opening with a jarring, heart-stopping scene in which David (Clayne Crawford) points a gun at his sleeping wife, Robert Machoian’s The Killing of Two Lovers is a riveting and restrained autopsy of a marriage in free fall. David and Nikki (Sepideh Moafi) have already separated, with David returning to his parent’s home. Their teenage daughter Jessica (Avery Pizzuto) takes it out on both parents, telling them to be the adults and work it out. The problem with that notion is that David and Nikki never had the chance to grow. Having Jessica young and four boys immediately afterward, they’ve stayed in the same small Utah town and moved only a few doors away from David’s childhood home. – John F. (full review)

Labyrinth of Cinema (Nobuhiko Obayashi)

Nobuhiko Obayashi is best known in the United States for his widely celebrated cult classic House (1977), but unknown to many of the noted auteur’s fans were his anti-war passion projects, propelled by his own childhood living under the shadow of Japanese nationalism in World War II. His epic three-hour swan song Labyrinth of Cinema embodies everything that is quintessential Obayashi, from the overcranking fast motion, to the striking visual colors overlaying the frame, and the frenetic editing that truly defines the maverick filmmaker’s oeuvre. Obayashi passed away in 2020 after filming and editing the film, and has left an indelible mark with one of the greatest films of his vast career. – Margaret R.

Lapsis (Noah Hutton)

Lapsis says and does a lot with its lo-fi aesthetics because it knows when to utilize its modest budget on computer graphic enhancements and when to let its endearing cast take the reins and run with things in a way that we can relate to as people caught in a similar cycle of economic warfare. And it’s Imperial who leads the charge with a deconstruction of the tough-guy persona trying his damnedest to wrap his head around things well past his pay-grade in order to seize this opportunity both socially and romantically (he’s into Anna). I’m still not sure what Hutton is doing with a cryptic ending I’m completely in the dark about, but it has me wanting to re-watch and discover what else I might have missed. – Jared M. (full review)

Les nôtres (Jeanne Leblanc)

It takes a village. That’s what close, tight-knit communities like Sainte-Adeline, Quebec, say when asked how they can confront and conquer tough circumstances. With that sense of togetherness, however, comes a cliquish sensibility of superiority. They survive because they have each other. They survive because they’re vigilant and always watching to see where and when their help is required to pick someone up. It’s how they got through a horrible construction-site tragedy years prior that claimed too many friends and families’ lives. They picked up the slack, opened their homes, and came out the other side. It’s also how they vindictively turned thirteen-year-old Magalie Jodoin’s (Emilie Bierre) life upside-down upon discovering she was too far along with an unplanned pregnancy to terminate. – Jared M. (full review)

Limbo (Ben Sharrock)

Two Africans, an Afghan, and a Syrian walk onto a remote island in Scotland. The punch line potential is infinite. Writer/director Ben Sharrock knows it too as he places them all in the same cramped apartment with a “Refugees Welcome” banner outside so they can argue about the merits of Ross and Rachel’s “break” courtesy of a burned Friends box set left behind by whomever lived there last. Add an eccentric cultural awareness course led by a duo in Helga (Sidse Babett Knudsen) and Boris (Kenneth Collard) who teach sexual harassment by having the former smack the latter’s intentionally handsy dance partner in the face and you’ll find yourself mimicking the class of foreigners watching in stunned silence thanks to the dryly humorous mix of confusion and horror. – Jared M. (full review)

Little Fish (Chad Hartigan)

Following his breakout film, the affecting character study This is Martin Bonner, and his follow-up, the vibrant fish out of water tale Morris In America, director Chad Hartigan had a prescient, ambitious vision for his next feature. Set during a global pandemic in which a growing portion of the population is affiliated with memory loss, Little Fish tenderly follows the relationship between a couple (Olivia Cooke and Jack O’Connell) as they must face this scary new world and the personal strife they are forced to reckon with. As Hartigan elegantly jumps between the past and the present to show all facets of the bond at the film’s center, he contends with the universal fear of having those closest to you drift away. – Jordan R. (full review)

Luzzu (Alex Camilleri)

Filmed and set in Malta, director Alex Camilleri’s debut Luzzu follows Jesmark, a fisherman and new father, in his attempt to find the money and resources to give his young family a good life. Set up by a simple premise and hyperrealist approach, the film pits dreams against pragmatism as Jesmark struggles to abandon his generational pull towards hitting the open sea in a tiny, hand-painted boat. As most audiences will find, we’re even less aware of Maltese life and this culture of fishing than we think. Camilleri, a Maltese-American, has spent the last decade working as an editor and assistant editor on a number of films, collaborating often with Iranian-American director Ramin Bahrani. Camilleri takes a naturalist path in his first film, edging on documentary fiction, his leading man (Jesmark Scicluna) with a hardened face and unwillingness to smile. – Michael F. (full review)

Malmkrog (Cristi Puiu)

In Malmkrog, a group of Russian aristocrats gather in a grand rural estate to wax philosophical during a long and luxurious dinner party. The film offers seemingly the closest thing to a direct screen staging of Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov’s War and Christianity: The Three Conversations. At 200 minutes, it runs just a few breaths short of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey but seldom ever leaves the confines of the decadent surrounding–indeed, the majority takes place in just three rooms. – Rory O. (full review)

Minyan (Eric Steel)

The year is 1986, the setting is New York City, and the AIDS epidemic is running rampant. Our hero David (Samuel H. Levine) is a teenager living in Brighton Beach, going to school while doing his damndest to get his grandfather (the great Ron Rifkin) into a retirement home nearby. The young man has a temper that stems from a budding rebellious streak, the long-gestating product of his strict Russian Jewish upbringing. Directed by Eric Steel, who co-wrote the script with Daniel Pearle, Minyan is a deeply personal piece of work. – Dan M. (full review)

My Heart Can’t Beat Unless You Tell It To (Jonathan Cuartas)

Landing somewhere between intense, realistic family drama and arthouse horror, Jonathan Cuartas’ My Heart Can’t Beat Unless You Tell it To is an oddly moving tale about social isolation, loneliness, and illness that resonates as a character study focused on the space of mourning. Dwight (Patrick Fugit) is a nightcrawler who spends his time hunting day laborers, the homeless, and other indigent persons living on the economic margins as a means of keeping his brother Thomas (Owen Campell) alive. Thomas, for all intents and purposes, is an undiagnosed vampire, warned by his waitress sister Jessie (Ingrid Sophie Schram) against leaving the house, especially during the day. – John F. (full review)

Old Henry (Potsy Ponciroli)

Henry’s (Tim Blake Nelson) been living and farming his Oklahoma land for almost two decades, if not more—the last ten as a single father to the now-teenage Wyatt (Gavin Lewis). Despite having help from his brother-in-law down the way (Trace Adkins’ Al), this life isn’t an easy one and the kid is desperate to escape it as much because of the work as the stone wall his dad has become. Wyatt feels he’s still being treated like a child when he knows he deserves more; Henry won’t let him hold a gun, let alone learn to shoot one. Tensions rise, Henry’s refusal to bend grows, and you can sense Wyatt is readying to leave the first chance he gets. Then everything changes. – Jared M. (full review)

El Planeta (Amalia Ulman)

In a café in Gijón, Spain, Leonor (Amalia Ulman) sits with a cup of coffee. An older man (Nacho Vigalondo) approaches her and joins her, and the two start discussing some sort of transaction. She’s considering sleeping with him for money, but then she reconsiders. “I’m wondering if it’s worth sucking a dick for a book.” Like Leonor’s own little gig economy she’s come to, this is one of the many vignettes El Planeta finds itself in. She was a fashion student in London before, but now that her father (and cat) has died, she’s home living with her mother (Ale Ulman), who’s facing eviction. The unemployment office has failed them and their time is scarce. Naturally, they start grifting to get meals and lower their bills. If someone else can pay for dinner, that’s great. If Leonor can sit in the hallway to read so she doesn’t have to turn on the lights, that adds up too. I’d be sad if it didn’t have such a droll approach. In some ways, it is. El Planeta isn’t the most thematically consistent, but it’s clever and brisk enough to be a good time. – Matt C. (full review)

Preparations to be Together for an Unknown Period of Time (Lili Horvát)

The hook for Hungarian writer/director Lili Horvát’s second feature doesn’t lack intrigue. Following a doctor who returns back home to Budapest after a chance, love-inducing meeting with another at a surgical conference, Preparations to be Together for an Unknown Period of Time––a mouthful of a title for the mystery-first drama––lives in the grey areas of the workplace, relationships, and loneliness. Once Vizy Márta (Natasa Stork) arrives to meet her hopeful-lover, Drexler János (Viktor Bodó), he’s nowhere to be seen, and after she finds him at the local university (and attached hospital), he seems to not recognize her. According to him, he’s never seen her before in his life. – Michael F. (full review)

The Real Thing (Koji Fukada)

With its massive runtime, circular story, and repetitive depiction of self-destructiveness, Kôji Fukada’s The Real Thing is the very antithesis to the classic meet-cute scenario. Based on Mochiru Hoshisato’s graphic novel, it was originally produced for Japanese television. The film has been slightly trimmed and spliced together for theatrical audiences at a still-hefty 232 minutes. Thus some of the eccentric charm that made it such a masterpiece of the serial format has vanished. Strangely, though, watching this maddening tale of love found, lost, and found in one fell swoop makes for a more sobering and heartbreaking experience. – Glenn H. (full review)

Rose Plays Julie (Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor)

Get ready for a tense ride because writers/directors Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor’s Rose Plays Julie never relinquishes its sense of brooding until the very last frame’s welcome exhale of relief. Why should they considering the subject matter? This is a dark story dealing with a reality too many women have experienced without the means for guaranteed justice. So while it might be a spoiler to say, I’m not sure it’s possible to speak about the film without mentioning how everything we witness is the result of a rape that occurred two decades previously. That event led to Rose’s (Ann Skelly) birth. It forced Ellen (Orla Brady) to explicitly state that she did not want her daughter to ever reach out. And its shared pain drives them today. – Jared M. (full review)

Saint-Narcisse (Bruce LaBruce)

Leave it to Bruce LaBruce to take the Narcissus myth and adapt it into a soapy twincest drama. Set in 1970s Canada, Saint-Narcisse follows the journey of a young, attractive, self-obsessed man who discovers he has a long-lost twin brother living in a monastery. Twists and turns abound, leading to a funny, blasphemous, and sincere (!) love story of an unconventional family unit. If anything, Saint-Narcisse is a nice reminder that it’s possible to be provocative and have fun at the same time. – C.J. P. (full review)

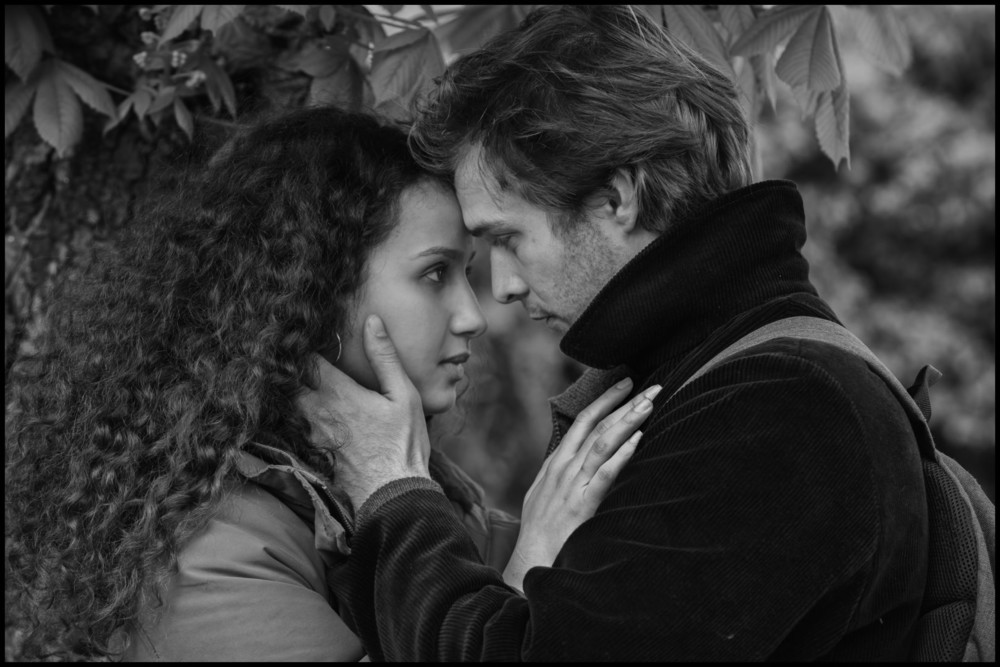

The Salt of Tears (Philippe Garrel)

People dismissed Philippe Garrel’s latest film after it premiered at the Berlinale in 2020, and in some ways it’s an understandable reaction. French films about a man navigating his way through life and love can feel like a dime a dozen, especially when it’s from a filmmaker who’s been doing this kind of story for years. But sit down and actually watch The Salt of Tears and you’ll realize that no one else is really making films the way Garrel does right now. His story of a young carpenter navigating several relationships while studying in Paris shows the selfishness and freedom of youth with plenty of specificity and barely any judgment, letting characters’ actions speak for themselves while the plot develops in a mundane, true to life fashion. By the time its abrupt, somber ending arrives, The Salt of Tears emerges as a snapshot of a time in one’s life when the world feels like it’s yours, until the day it suddenly isn’t. – C.J. P.

Sator (Jordan Graham)

Jordan Graham’s second feature Sator is a labor of love for the filmmaker, taking him more than seven years to complete as he handled almost every single role behind the camera (all the way down to building the main character’s house). It tells the story of a reclusive man living in a cabin in the woods, who finds himself to be the next target of a demon that’s been terrorizing his family for generations. Due to its small budget and DIY production, Sator keeps things minimal and smart, with its reliance on what’s outside the frame leading to plenty of nerve-wracking moments. Even more surprising is the film’s blending of fiction and non-fiction; Graham seamlessly weaves in footage of his late grandmother, whose testimony about being possessed formed the basis of Sator’s story. – C.J. P.

Slalom (Charlène Favier)

A chilling, controlled pressure cooker of a film, Charlène Favier’s Slalom brings attentive nuance to a story of psychological and sexual abuse. Set amongst the slopes of the French alps, the Cannes-selected drama centers on Lyz Lopez (Noée Abita), a 15-year-old skiing prodigy whose life is more or less controlled by her callous instructor Fred (Jérémie Renier). With his predatory advances shrouded and twisted in the mutual desire for competitive success and filtered through the young girl’s initial intrigue, Favier expertly delves into the psychological prison that soon becomes her daily existence. Far from a one-note #MeToo message movie, Slalom brings a poignant sense of restraint with fleshed-out characters for a thoroughly unnerving experience. – Jordan R. (full review)

Slow Machine (Joe Denardo and Paul Felten)

It’s rare that a new American film feels genuinely alive with possibility from beginning to end. So many of the logistical, economic, and technological decisions that go into making a movie in the United States are designed to suffocate artistic vision in favor of audience accessibility. Which means something infinitely strange and fractured like Slow Machine feels all the more essential, an eccentric celluloid shape-shifter shot on 16mm that playfully upends the tropes of narrative storytelling. – Glenn H. (full review)

Sophie Jones (Jessie Barr)

Plenty of coming-of-age films arrive each year, and it takes something special to stand out from the crowd. Sophie Jones manages to do just that by utilizing an approach that values authenticity above all else. Jessie Barr, making her feature directing debut, has a naturalistic touch that envelopes you in this world, placing you back in the headspace of a teenager, regardless of your gender. Whether it’s the rich layers and contradictions given to the awkward, narcissistic, sometimes defensive Sophie (Jessica Barr, the director’s cousin) or the unconventional costume and set design, with the Barr ladies making use of their actual clothes and shooting in Jessica’s childhood home, there’s a lived-in quality to Sophie Jones that elevates it to must-watch material. – Mitchell B.

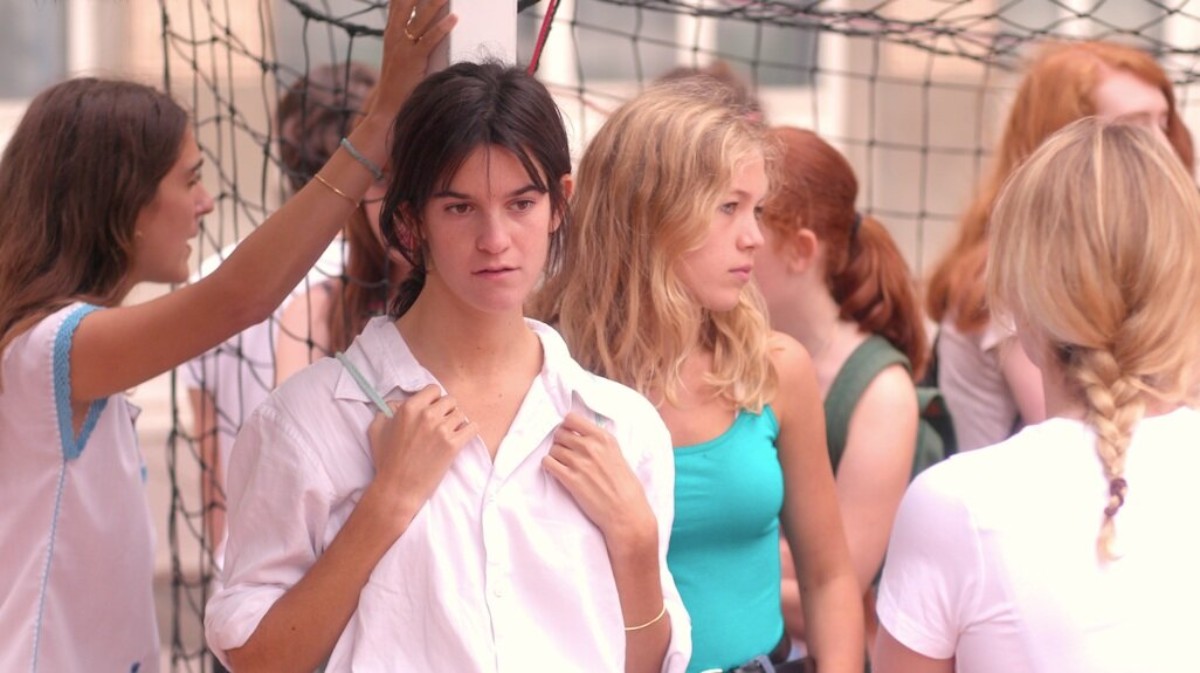

Spring Blossom (Suzanne Lindon)

It takes great maturity and confidence to make a film about the emergence of a young woman’s sexuality that also dares to ask complex, provocative questions while understanding there are no simple answers. Suzanne Lindon is such a filmmaker, and her brisk, entertaining debut Spring Blossom is such a film. Lindon directed, wrote, and stars in this remarkably assured story of a 16-year-old Parisian who falls for an older man. Though Blossom is a bit slight at just 73 minutes and sometimes prone to posing too many questions, this TIFF entry heralds the arrival of a major international talent. – Chris S. (full review)

Sweat (Magnus von Horn)

Sweat is one of the best films about an influencer that has been made to date. While other films about social media dismiss their characters as vapid, Magnus von Horn’s latest has so much empathy for fitness influencer Sylwia (Magdalena Kolesnik). Von Horn places blame on the mechanisms of social media for Sylwia’s sadness. It’s a film that peels back the masks we wear online and questions whether we ever stop performing for our followers. – Orla S.

Sweet Thing (Alexandre Rockwell)

Alexandre Rockwell’s Sweet Thing could be pulled from any era. Shot in striking 16mm black-and-white, the coming-of-age film—Rockwell’s first feature since 2013—is an intimate story about childhood, connection, freedom, and the stories we tell ourselves to survive. Starring Rockwell’s own children Lana and Nico as, respectively, Billie and Nico, Sweet Thing keeps its lens on two children maturing before they should and forced into situations of adulthood. – Michael F. (full review)

Take Me Somewhere Nice (Ena Sendijarević)

Ena Sendijarević’s gorgeous debut feature Take Me Somewhere Nice is a tale of fractured identities, a Bildungsroman that zeroes in on a teenage girl traversing two irreconcilable worlds, each demanding her undivided allegiance, none close enough to be called home. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Test Pattern (Shatara Michelle Ford)

Every new romance begins with the fantasy of everlasting happiness. Film as an art form is adept at capturing the intensity of euphoric early moments shared between two love-struck people discovering each other for the first time. Audiences know this is merely a precursor to the reality and heartbreak that comes next, but we still flock to love stories nevertheless. Shatara Michelle Ford’s Test Pattern is one of the most unique and sobering deconstructions of this classic construct. The cutesy first act finds corporate manager Renesha (Brittany T. Hall) falling in love with hipster tattoo artist Evan (Will Brill) after they meet-cute at a bar one night. While their early conversations are stilted and groggy, the two are drawn to each other in ways that are not entirely explainable. Honeymoon phases rarely make a lick of sense. – Glenn H. (full review)

This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese)

When observing global cultural differences, some of the most telling points of distinction are seen in how different societies treat death. Beyond this, the ongoing 2020 pandemic has resensitized us, especially in the west, to an earlier way of life not seen since the two world wars and the emergence of modern medicine, where the specter of death looms larger. A certain mode of arthouse film is well-equipped to process these ideas. The deeply referential new South African film This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection strongly evokes Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, perhaps cinema’s greatest contemplation of the subject. – David K. (full review)

True Mothers (Naomi Kawase)

True Mothers is one of Naomi Kawase’s most plot-heavy, novelistic films, and also one of her best. It’s a dual narrative about two women: the adoptive mother of a young boy, and his birth mother. Kawase beautifully weaves their stories together in a film that’s rich with psychological complexity and so empathetic toward every character on screen. – Orla S.

The Wanting Mare (Nicholas Ashe Bateman)

The Wanting Mare, the directorial debut of Nicholas Ashe Bateman, can feel overwhelmingly beautiful and purposefully abstract. Its billing has compared it to The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones for its fantasy-building, lauded for its technical achievement on a shoestring budget and referenced as a darker fable akin to Pixar’s Onward. These analogies at once credit the movie’s ambitious aesthetics and exemplify its vague storytelling, bound with potential and challengingly little detail. – Jake K.S. (full review)

Wet Season (Anthony Chen)

Gene Kelly likes to sing in it, Spider-Man is known to kiss in it, but moody old melodrama remains the most reliable companion to rain at the movies. This is at least evident in the new Singaporean film Wet Season, in which a foreigner who teaches Mandarin at a city high school strikes up an increasingly troublesome but mutually vital friendship with one of her students. It buckets down continuously. – Rory O. (full review)

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? (Aleksandre Koberidze)

What did the drain pipe, the security camera, and the sapling say to the girl when she crossed the road? This is the set up, not of some shitty joke, but of a key scene of dramatic conflict in Aleksandre Koberidze’s What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?. At the beginning of the film, Lisa (Oliko Barbakadze) and Giorgi (Giorgi Ambroladze) have an odd meet cute in the streets of the Georgian city of Kutaisi. They fall in love at first sight, arrange to meet at a cafe the next day, and forget to ask each others’ names. As Lisa heads home, the pipe, camera, and sapling decide to warn her of encroaching danger. As recounted to us by a narrator (voiced by director Aleksandre Koberidze), they tell Lisa that an evil eye observed her meeting with Giorgi and has cursed them. The next day, she will wake up looking like a different person, and he will be unable to recognize her. But there was a final part of the curse that Lisa didn’t hear; the wind was supposed to tell it to her, but got cut off by passing cars. Unbeknownst to him, or to Lisa, Giorgi will also wake up looking like a different person. When they next see each other, they’ll see a stranger. – Orla S. (full review)

Wild Indian (Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.)

What is the cost of violence? In Wild Indian, the answer is never-ending. Examining the drastically opposing life paths taken by childhood friends Makwa and Ted-O (Michael Greyeyes and Chaske Spencer), Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s film burns with a deeply unsettling atmosphere—a rage that permeates every scene. This is a startling debut from Corbine, so confident in tone, trusting the audience to be on his wavelength—which can be quite austere and off-putting at times. It’s all done with intention, an intrinsically Indigenous story told by an Indigenous filmmaker that could only be made through this specific lens. Wild Indian is challenging in the way that a Michael Haneke movie is challenging, where it gets to these core ideas of the darkness of human beings, and specifically here the bloodied soil that we’re all living on. – Mitchell B.

The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin) (C.W. Winter and Anders Edström)

“It’s sad to get old in any period.” Tayoko (Tayoko Shiojiri) has just watched Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story on television and it’s struck a nerve of melancholy. The Japanese master’s great films tend to do this to viewers, especially those who find themselves in the midst of painful transition. Her husband Junji (Kaoru Iwahana) has become increasingly ill over the last few months, and the slow passage of time has suddenly taken a different meaning for the woman who spends so many hours outside in the fields cultivating crops. This observation about aging comes in one of many journal entries that comprise the spine of The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin), an experimental study in duration and devotion that intricately overlaps voiceover and ambient sound design to create a symphonic cinematic space in the quietest of locations. – Glenn H. (full review)