During the early life of The Film Stage, we set out to chronicle the 2000s with our 100 favorite features. In the last five years, as we’ve grown and our tastes have evolved, it’s now time to take a look at the demi-decade. In culling from individual lists of 15 contributors, we’ve highlighted our 50 favorite films released since 2010. Check out the cumulative list below, then head to the last page for individual ballots. If you’d like to keep track via Letterboxd, you can do so here.

50. Enemy (Denis Villeneuve)

It is a story as old as the ages: man comes face-to-face with himself and chaos ensues. What makes Enemy different, however, is the incredible richness built into and around this simple narrative. For one thing, Jake Gyllenhaal invests both of his characters with so many small physical characteristics that there is never a question about which of the doubles we are looking at in any given moment. This physicality allows him to build fully realized and distinctive human beings out of two men who look exactly the same, and to create a disparity and a tension that is engrossing to behold. Add to this performance the dense layers of rich visual symbolism, and you have a movie that is a strange, wonderful work, and one of the most enthralling and enigmatic films in years. – Brian R.

49. Martha Marcy May Marlene (Sean Durkin)

One of the most accomplished directorial debuts of the decade thus far, Sean Durkin‘s Martha Marcy May Marlene is a suffocating, stripped-down character study of manipulation and trauma. Through dream-like editing, we’re trapped in the fractured mind of Martha (Elizabeth Olsen, giving a subdued, intoxicating break-out performance) as we weave in and out of her perception of the past and the semblance of life she’s attempting to live in the present. In a rare feat, what Durkin has assembled manages to burrow into one’s psyche and linger long after the exemplary final scene. – Jordan R.

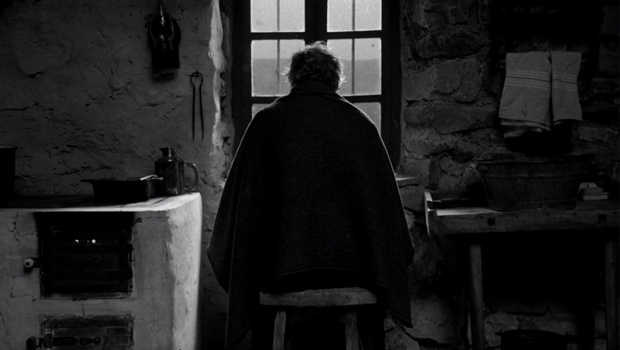

48. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr and Agnes Hranitzky)

For those unfamiliar with the cinema of auteur Béla Tarr, his style is marked by a few distinctive traits. From his use of moody black and white cinematography with shots often lingering unbroken for several minutes to the stark portrayal of his local Hungarian culture, the filmmaker creates an uncanny sense of time and place akin to Russian legend Andrei Tarkovsky. Based loosely on a story about Friedrich Nietzsche going insane, The Turin Horse is an existential examination of mundane daily life filtered through Tarr’s unique style. It is also a searing vision of a looming apocalypse, transforming the themes of the film into a metaphor for the weight of mortality that life is forced to bear. – Raffi A.

47. Tuesday, After Christmas (Radu Muntean)

Director Radu Muntean takes a style firmly lodged in the Romanian New Wave lineage and applies it to domestic, everyday material: a man’s two-sided love life, his affections split between his wife and a new, younger girlfriend. Muntean’s intricate, ever-evolving single-take feats provide total access to disarmingly convincing snippets of natural human activity — it’s hard to top A.O. Scott’s use of the word “pornographic” in describing our witnessing the catastrophic collapse of one of the movie’s core relationships. The behavior is so real that watching it feels illegal, uncalled-for — and thrilling. – Danny K.

46. To the Wonder (Terrence Malick)

A Terrence Malick film is an event, no matter the time or the subject, but it is undeniable that there’s something markedly different and all-together special about To the Wonder. Perhaps it’s Malick’s transition from period pieces into the modern world, or the tight focus on people whose only extraordinary circumstance is their search for love. Either way — and for whatever reason — Malick has never felt more sentimental or raw than he does in this film. There is a reality to this film that even his other masterpieces shied from, and his unflinching gaze at the way in which love ebbs, flows, grows, and evolves lays bare the romantic lies in almost every other film ever made. This is to say nothing of his trademark visual style, which makes even bland suburbs and fast food restaurants looks hauntingly lovely. To the Wonder confused people when it first came out, but, as The Film Stage Show proved, with time and understanding, regard for this film can and does grow stronger. – Brian R.

45. Welcome to New York (Abel Ferrara)

A younger, unchecked Abel Ferrara might have made something louder and more aggressive out of this tawdry material, but this study of a monster is disciplined and startlingly de-sensationalized. Ferrara’s formal approach — dim lighting, long takes — prioritizes depiction over commentary; while there’s no questioning the deplorability of Devereaux’s (Gérard Depardieu) cravings, Ferrara doesn’t waste time moralizing. The reason for this is wise and ingeniously simple: after enough time in Devereaux’s company, the man will simply render himself pathetic. The project couldn’t have clicked without a committed central performance, and the one Depardieu turns in is heroically vulnerable. The excruciating, near-real-time sequence in which the actor is detained, processed, questioned, and stripped in a police department is process-oriented filmmaking at its most revealing. – Danny K.

44. A Burning Hot Summer (Philippe Garrel)

What makes Philippe Garrel’s films so distinct is their blend of autobiographical pain and silent-film mise-en-scène — a failed relationship or revolution rendered not so much through the increasingly dialogue-heavy scripts of his films, but the placement of bodies, gestures, and, furthermore, the dreams that contain and emerge from them. Yet while A Burning Hot Summer may be the only film he’s made in the 21st century not shot in black-and-white, once the senior Maurice Garrel (in his final role) appears as an apparition in his grandson’s hospital bed-bound vision, the personal and the fantastical have formed their most natural relationship. – Ethan V.

43. Room 237 (Rodney Ascher)

A movie is just a movie, unless, of course, it’s the director’s sly way of telling the world that he faked the moon landing. That’s just one interpretation of The Shining presented in Rodney Ascher‘s first feature documentary, which examines the many theories surrounding Stanley Kubrick‘s horror masterpiece. The range of subjects, including a respected journalist, an academic, and a known conspiracy theorist, creates a varied look at just how deep film analysis can go, where everything from minor props to continuity errors come under massive scrutiny. It also demonstrates how our backgrounds and experiences dictate our relationship with film, making it one of the most fascinating documentaries about cinema ever produced. – Amanda W.

42. Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage (Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn)

Directed by Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen, Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage is one of the best rock ‘n’ roll documentaries ever made and one of the best movies about music since Almost Famous. Beyond the Lighted Stage is a comprehensive look at three boys from Toronto who make good, and make brilliant music for over 30+ years. A love letter of sorts that’s both personal and historic, Dunn and McFadyen incorporate historic footage, images, performances into present-day sit down interviews with Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart, along with insightful talking heads of their musical contemporaries. The film’s most fascinating passages demonstrate how Rush has evolved, tackling genres from hair metal to grunge along with electronica and jazz – there’s nothing these three boys can’t do. A triumphant, sweeping behind-the-scenes documentary released just as Rush was finalizing their long awaited Clockwork Angels album, it’s the kind of movie that inspires a standing ovation in the theatre. – John F.

41. Enter the Void (Gaspar Noé)

Enter the Void is a rare example of pure cinema, a transformative experience so intense that, by the end, your eyes might be bleeding. French filmmaker Gaspar Noé pushes the envelope with amazing aerial camera techniques used to create an enveloping sense of floating like a spirit in the afterlife. It also has arguably one of the greatest opening credit sequences in the history of cinema. This film is a testament to Noe’s ambition and skill, whose rebellious and unconventional attitude makes him akin to a modern day Jean-Luc Godard. While his graphic subject matter may be a turn off for some, at its core Enter the Void is an uncanny experience that will leave you unnerved and mesmerized. – Raffi R.

40. The Grey (Joe Carnahan)

Liam Neeson has become known for playing the kind of men that we all hope we can grow to become – stoic, rugged, and endlessly capable. So the idea of throwing him to the wolves, literally, and seeing how he could handle himself makes sense. It is hard to conceive of how anyone could be disappointed or surprised by the effectiveness of Liam Neeson in a lost-in-the-woods story, but what is surprising is the rich emotional and existential core at work in The Grey. Nature and Man become two primal forces, each vying for purchase against the other, and the concept of the choice of survival becomes a raw, tactile function of the plot. The direction by Joe Carnahan is beautifully evocative and visceral without being overly showy. It is the perfect balancing act between action and an almost spiritual dialogue, and one of the biggest and most profound surprises of the demi-decade. – Brian R.

39. Ida (Paweł Pawlikowski)

A beautiful film that’s only grown in my personal regard over the last year, director Paweł Pawlikowski tells a short, specific kind of story wrapped in the immediate tragedy of World War II. Featuring two beautiful turns by Agata Kulesza and Agata Trzebuchowska, Pawlikowski has made a modern masterpiece that wades in melancholy and lost moments with enough lyricism and visual poetry to be unforgettable. – Dan M.

38. Cloud Atlas (Lana and Andy Wachowski & Tom Tykwer)

Cloud Atlas is one of the most ambitious films of the decade, deserving of a space along side other sweeping epics traversing the bounds of space and time like Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. Directed by Lana and Andy Wachowski and Tom Tykwer, it’s a near-perfect marriage of the directors’ styles and sensibilities (although, truth be told, Tykwer — known for his film’s about destiny, choice and intersecting lives in Winter Sleepers, The Princess and the Warrior, Heaven, and Three 00 seems to be the dominant influence here). Cloud Atlas is a carefully constructed ballet that in theory should not work with a mix of broad humor, space opera, historical melodrama, jungle adventure and gritty 70s thriller. It’s a mash-up that should make even Guy Maddin jealous, connected across multiple universes, times and locations. Running three hours, Cloud Atlas wastes not a frame, resulting in a powerful and ambitious picture that rewards repeat viewing. – John F.

37. Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino)

Quentin Tarantino’s affinity for African-American culture is no secret, as his filmography boasts a generous share of powerful black characters and blaxploitation homage. But never has his obsession been more apparent than in his down-and-dirty western, which follows a freed slave (Jamie Foxx) who, with the help of a German bounty hunter (Christoph Waltz), sets out to save his wife (Kerry Washington) from a merciless plantation owner (Leonardo DiCaprio). Foxx and Waltz display a fantastic chemistry as the two leads, and are equally pitted against DiCaprio’s maniacal Calvin Candie and his manipulative house slave, Stephen (Tarantino regular Samuel L. Jackson). The daring thriller isn’t afraid to depict the horrid realities of slavery as it shoots and burns a path to revenge, which makes for a spectacular, yet brutal experience. – Amanda W.

36. Oslo, August 31st (Joachim Trier)

An odyssey into a lost soul from Joachim Trier. The film serves as a representation of its addiction-riddled hero, Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie): dark and dreadful, but also sweet and vulnerable. Set over one day, Trier does great work capturing the intense difficulty of waking up in the morning and living your life. – Dan M.

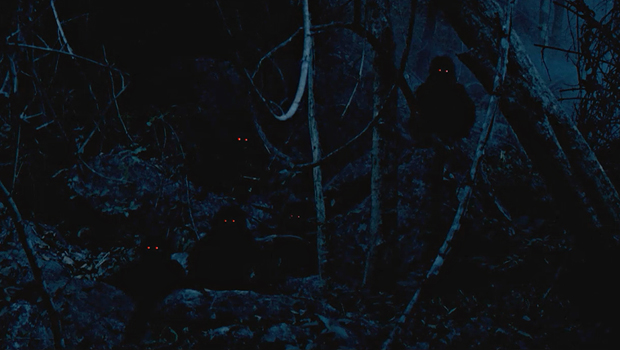

35. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

The degree to which Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s (or if you prefer, Joe’s) masterwork mystified the majority of worldwide festival audiences in the wake of its 2010 Palme d’Or victory would make it seem a picture determined to push one away rather than lure. Though even when approaching the film’s rather specific spirituality as something of an outsider, the relaxed and humorous nature with which it goes about a magical-realist cycle of life, death, and the hereafter reveals a work completely open to possibility. – Ethan V.

34. Horse Money (Pedro Costa)

With Lisbon’s Fontainhas neighborhood, the subject of a past trilogy of his films now just a memory, Pedro Costa may have felt the need to move on. He even admitted to the difficulty of making the film, due to both an attempt to employ quicker pacing and depict violent subject matter, which was, of course, maybe fruitless, considering those who still labeled it a purposefully alienating work — or, rather, “airless installation piece.” But the film’s account of past trauma couldn’t be more relevant, not just because it so sadly alludes to now, but, as expressed with its perfect final shot, the inevitable struggle that’s still ahead for decades to come. – Ethan V.

33. Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Paravel)

A film practically overflowing with images that would’ve been a total impossibility only several years ago, captured through the eyes of a camera that itself turns the most natural of images into something horrifyingly alien. Leviathan has a strong “spectacle” quality to it, sure, but its vision of nature’s uncompromising force is so compounded by a careful assembly of sequences — right down to a final dedication card — that the fusing of sensation and perception makes it nothing short of a benchmark. – Nick N.

32. Don’t Go Breaking My Heart (Johnnie To)

A prime example of the wild, infectious imagination that goes into the collaborations between Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai: one character here (Daniel Wu), first seen wandering the streets of Hong Kong while taking pulls from a bottle of Johnnie Walker, soon reveals himself to be a depressed architect (!) and a chief romantic interest for the conflicted protagonist (Gao Yuanyuan). Equally surprising is the movie’s screwball-friendly premise, which, in situating the three main characters in close geographical proximity, takes on the playful quality of being a love triangle told through gleaming, office-building windows. The overall skepticism here regarding love in a post-recession global landscape strikes a constructive balance with the movie’s contagious surface pleasures — joyful physical performances, corny soundtrack choices, and corporate structures seized with wide-angle lenses. – Danny K.

31. Drive (Nicolas Winding Refn)

“It was no surface but all feeling,” sang Welsh rockers the Manic Street Preachers on 1996’s Everything Must Go. Fifteen years later came Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a film best categorized as all surface but no feeling. Therein, perhaps, lies part of the appeal. For Drive is sensory overload — the glossy downtown Los Angeles visuals, the electro-pop score — with little import placed on dialogue, or plot for that matter. Ryan Gosling, Carey Mulligan, Oscar Isaac, Albert Brooks, Bryan Cranston, Ron Perlman, and Christina Hendricks are ideally cast and tonally perfect, but this is Refn’s show. Quite simply, there is something about Drive that lingers in the memory. I recall shrugging my shoulders after my first viewing of the film, yet realizing several days later that I could not stop pondering it, visualizing it, hearing it. It is pure existential pop perfection. – Chris S.

30. Another Year (Mike Leigh)

Balancing humor and sadness, often on screen in the same moment, Leigh crafted his best film since Secrets & Lies with Another Year. Tracing four seasons of joy, pain, and misery in the life of Tom (Jim Broadbent) and Gerri (Ruth Sheen), along with their son Joe (Oliver Maltman) and troubled friend Mary (Leslie Manville), it’s often uncertain, fascinating and compelling. A return to the working class kitchen dramas of Leigh’s early career, Another Year is a rich, emotional experience representing the best of Leigh’s work. It’s a must-see for both neophytes and devotees. – John F.

29. Take Shelter (Jeff Nichols)

Shot through with a visually alluring paranoia, Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter is a tremendous exploration of cultural uncertainty and anxiety weighted against interior madness. All of this is done with great care and artistry. There’s no frame of Shelter that isn’t engaging or perplexing and it takes its time to be good; building an architecture of dread out of its mundane family scenario, the surrealistic fear of the dream sequences, and from the tremendous performance of Michael Shannon, who looks as if he heard the final trumpet sound hours ago and the horsemen are already on their way. What Nichols has made is a sympathetic and realistic look at the anxiety of coping with mental illness (both from the perspective of the afflicted and those who care for them), and to a lesser extent, that gripping anxiety that all of us struggle with, in some form or other, every day. – Nathan B.

28. The Immigrant (James Gray)

Although essentially nothing about The Immigrant is difficult to grasp as it’s occurring, there’s nevertheless something mysterious about its cumulative effect — more specifically, why a film of such obvious, albeit clean-cut elegance earns the sort of plaudits often directed toward works of larger scales and greater ambitions. Subsequent viewings of James Gray’s classically minded melodrama might be all you need, given how neatly the larger whole coheres and the extent to which its narrative through lines build toward something of a strangely modest significance. Not a hair feels out of place. Oh, and the last shot will eventually earn its place as one of the greatest in all of cinema. – Nick N.

27. Before Midnight (Richard Linklater)

The blissful romance found in the first two Before films is assuredly not the backbone of Before Midnight, yet Richard Linklater‘s meditation on the progression of love is anything but cynical. Presenting something more real and honest, we catch up with Jesse and Celine nine years later as they’ve now experienced many years of committed relationship. By showing the actualities of a lifetime of love, evolving from their euphoric initial infatuation in Sunrise to, now, an authentic, complex examination of its struggles and delights, Before Midnight is the most romantic of the series. Even if we never return to this story, Linklater’s trilogy presents one of cinema’s most relatable relationships and marks perhaps his finest accomplishment. – Jordan R.

26. Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson)

Wes Anderson’s leap through the animated realm was a key moment that shifted his filmic characterization toward metaphysical poignancy, thus making way for Moonrise Kingdom, an impressionistically stylized portrait of a pre-Vietnam adolescent bliss. It’s not just Pierret Le Fou for children, but a story about the recreation of storytelling, appropriating aesthetics from low and high arts to burn memories of innocent times as a protection against the fears of adulthood, portrayed here as a melancholic, mid-life stasis (Norman Rockwell’s hard faces as imprints of immobility). What sympathizers to his visual language often miss is that his imperceptible framing not only engages a constant succession of spatial humor (cuts always matter), but, ultimately, a type of storybook visual prose that plays out into Anderson’s larger stakes of mixing brief penetrations of emotional honesty into carefully calculated pictoral surfaces, an update of Renoir’s A Day in the Country (the ending implied by the impressionistic image that is the final shot). The past is all prologue here, and it matters. – Peter L.

25. Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi)

Never mind that early reviews of Taxi are enormously positive; take any one of Jafar Panahi’s post-imprisonment films and it becomes immediately clear that harsh conditions seem only to invigorate the director, turning him into perhaps the most vital filmmaker of the ‘10s. Closed Curtain opts for a surrealist angle on Panahi’s imprisonment, following the director as he’s haunted by the ghosts of his simultaneously realized and unrealizable creations. The film takes one turn after another, as if a real-time chronicle of Panahi’s state of mind, and yet each moment seems to accumulate insight into the political, technological, and artistic. In light of a Golden Bear win for Taxi and the official response, it is too simple to say that Panahi “can’t make films,” but such a paradox only makes Closed Curtain a more complex work, capturing the contradictions and hypocrisies of his filmmaking and travel ban. – Forrest C.

24. Mysteries of Lisbon (Raúl Ruiz)

This is not his final work, but Chilean master Raúl Ruiz’s four-hour-plus Portuguese melodrama works as both a beautiful vision of 19th-century aristocracy critique and a vision of the beauty and necessity of storytelling itself. Very few events happen in the plot proper, instead escorting us from flashback into flashback (Cervantes-style), each long history revealing a key detail about the young adolescent without a last name in Europe during the Napoleonic Wars. Ruiz’s camera dollies through the action with a ghostly presence, reframing sequences for melodramatic reveals with clever ruptures of traditionally material space, treating memories more like visual playgrounds than actual spaces of reality. And in a tale that includes countless alter-egos, buried secrets, and death-bed confessions, it seems natural that the tale of one’s learning their personhood — an almost predestined series of accidental consequences — would take place somewhere between reality and the melodramatic construction of it, an interrelated series that essentially helps us understand the need for fiction to recreate the past. – Peter L.

23. Shame (Steve McQueen)

Visual artists-turned-filmmakers possess a level of formal singularity others don’t. Contemporarily, Steve McQueen exemplifies this truth. No matter how auspicious his debut Hunger or successful his Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave, Shame is his masterpiece. A profound portrait of mankind’s emotional turmoil and infinite yearning to fill an unfillable emptiness, this look at sex as an escape from intimacy drips with despair. The camera gazes as Michael Fassbender journeys through the harsh landscape of his Brandon’s shame, an orchestral score deafening every attempt to quell the numbness he cannot outrun. Uncompromising and haunting, his spiraling descent after being forced to confront the one person he’s ever truly loved isn’t easily shaken. – Jared M.

22. The Deep Blue Sea (Terence Davies)

One of the great romances of the 2000s. Tom Hiddleston and Rachel Weisz shatter hearts as star-crossed loves, one a RAF pilot the other the wife of a High Court judge. Both struggle with bouts of depression and self-doubt in different ways, destroying themselves and each other without any intention to do so. As wonderful as the film is to look at, there’s a brutalism in Terence Davies‘ direction that touches on the impossibility of love for most, if not all. – Dan M.

21. Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson)

At once Paul Thomas Anderson‘s loosest and densest film, Inherent Vice presents a world that’s easy to get lost in. Not because his adaptation of Thomas Pynchon‘s novel isn’t interested in hand-holding — it is a mystery from the point-of-view of a paranoid and confused pothead, mind you — but its melancholic tone, the Blake Edwards-like comedy, and array of endlessly eccentric characters, all of which add up to a transcendent two-and-a-half hours. This is a movie that washes over its viewers as long as they’re willing to go along for the trippie ride. It’s a strange, funny, and surprisingly sad story, almost more about a bad breakup than the mystery Doc has to unravel. Shasta Fay’s (Katherine Waterston) presence is almost always felt in Inherent Vice. Doc confronts equally confusing internal and external struggles in this dreamlike LA story. Despite a disappointing box-office, it’s up there with Anderson’s best work. – Jack G.

20. Margaret (Kenneth Lonergan)

Set against the backdrop of America’s lost exceptionalism in post-9/11 New York City, Margaret is one girl’s attempt to reconcile the fact that everybody is the protagonist of their own lives with the fact that such a thing does not make you the center of the world. Unfairly maligned on initial release, perhaps because of the film’s long, troubled history, it didn’t take long for Margaret to be reclaimed as one of the decade’s best — particularly in the DVD-only “Extended Cut” (not “Director’s”). Regardless, what emerged is astonishing, a dense, narratively ambitious work that flaunts director Kenneth Longergan’s pedigree as an esteemed playwright that nevertheless reaches many of its enlightenment and conclusions by virtue of its sound design. A scene will begin allowing us to hear other people’s conversations, only for them to gradually diminish as the camera approaches Lisa (Anna Paquin), placing the film’s paradoxical tension into one cinematic device. – Forrest C.

19. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

A police procedural unfolds in the dimming twilight of an Anatolian countryside with a group of archetypical men — a police commissioner, a physician, a lawyer and a prisoner — searching for a woman’s body. This is the platform but not the subject of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon A Time In Anatolia. Pursuing the ghosts of filmmakers like Krzystof Kieslowski and Andrei Tarkovsky, Ceylan imagines his films as terrariums of image, sound and life living itself out in an environment where it can be turned and studied. The visual component of Anatolia is perhaps its most profound, an irony not lost on Ceylan who wants us to consider the interior souls of these men by becoming careful observers of their exteriors and the serene but lonesome landscape they inhabit. Watching Anatolia is sometimes like looking through the eye of God, taking in the comings and goings of figures less significant than they seem, with great interest but without judgment. – Nathan B.

18. Goodbye to Language (Jean-Luc Godard)

Breaking the rules has always been something that Jean-Luc Godard seems to naturally gravitate towards. His latest film, Goodbye to Language, is no different, an acid trip into life, language, and the lunacy of the modern condition. The impressionistic use of 3D is reminiscent of the way he subverted digital technology with In Praise of Love during the advent of digital cameras, by shooting half of that film in black-and-white 16mm and the other in standard video format. Godard similarly uses different expressions and the third dimension to startling effects, like only a true artist who appreciates the complexity of the medium would. Bizarre, brazen and bold, it’s so refreshing to know that, at the age of 84, Godard has never felt more alive. – Raffi A.

17. Exit Through the Gift Shop (Banksy)

The question of whether or not Banksy actually directed Exit Through the Gift Shop doesn’t diminish the fact that the irreverent documentary cemented his already mythic status. The mysterious street artist, whose identity remains unknown, pulls a fast one on the public by creating and promoting a fake protege called Mr. Brainwash, who’s immediately hailed as the next big thing. The elaborate prank exposes the cult of the celebrity artist, and examines how the graffiti art movement went from an illegal pursuit shrouded in anonymity to a commercialized phenomenon. Five years after its release, the film’s commentary rings more true than ever as Banksy’s provocative images now grace everything from t-shirts to throw pillows. – Amanda W.

16. Melancholia (Lars von Trier)

Two acts. Two bodies. One a sad young bride on her wedding night; the other a mysterious blue planet previously hidden behind the sun that’s now on a collision course for Earth. Inspired by writer/director Lars Von Trier‘s own bouts of depression, Melancholia expresses the pain, guilt, and overwhelming sense of nothingness accompanying the condition. Initially one lost soul adrift in the life her friends and family declare normal, Kirsten Dunst‘s Justine is deemed a frustrating, selfish woman who can’t get out of her own way by the rest. Only when existence itself is threatened, when the world literally closes in, can they understand. Life is but a blink: unspecial, insignificant, and always expiring no matter surface decadence or beauty. We fear the worst because the worst forever looms. Perhaps delusion is our inability to accept that truth. – Jared M.

15. Cosmopolis (David Cronenberg)

In an era of “Big Data,” David Cronenberg’s artificially articulated Cosmopolis takes us through the journey of a billionaire whose belief in digital patterns is questioned when he’s unable to comprehend a disastrous fall in the yuan — chaos theory crashes complex theory. In Cronenberg’s world, digital life is a cracking façade: monotonous dialogue pops like a screwball comedy, the limousine slowly deteriorates into a piece of junk (its windows convey “the real world” through a wonderfully antiquated use of rear projection), and our protagonist’s body physically corrodes in the most absurd of ways. Edited and shot with razor-sharp skill, Cronenberg’s adaptation of Don DeLillo’s prose considers the impossibility of analyzing functions in the fluctuation of signs and symbols of today’s digital life. Nothing is exactly real until reality fractures a world of predictable patterns. Two characters realize they both have asymmetrical prostates, but the meaning is negligible: “Nothing… a harmless variation.” The most unsettling thing in Cronenberg’s vision of the future is realizing that not everything can fit neatly into models. – Peter L.

14. Upstream Color (Shane Carruth)

Disorienting, obtuse, beautiful — Shane Carruth‘s Upstream Color is many things. A metaphor for life’s infinite cycles, our invisible connectivity to nature, and the desire for independence to acquire peace, it’s a film speaking volumes in its silence while harboring meanings as varied as the individual watching. Mind control, psychic linkage, and spontaneous aggression wreak havoc as two souls caught in an intricate web of parasitic nature are spied upon from afar. Consciousness is split, reality bent, and the key to everything trapped until the subject learns to peer back at its oppressors. We all face existential crisis, losing ourselves to unseen societal powers that dictate our actions. To break free is to live. To see the world as your own a clarity only achieved with the courage to fight back. – Jared M.

13. This is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb)

“It’s not just a movie — it’s a message” is the sort of campaign-friendly terminology that often goes hand-in-hand with movies aiming to tell us about the importance of a single person, movement, or idea, ultimately dulling everything around it through such proselytizing. So I’ll be careful when praising This Is Not a Film, both the first in what, by now, is clearly a new phase of Jafar Panahi’s career, as well as a thunderous (and slyly meta-textual) statement on the role makers play in our perception of art. Even if its stark ending weren’t somewhat alleviated by the recent possibility of light at the end of Panahi’s creative tunnel, this would be as critical a document of cinematic expression as anything else composed in the last few decades. – Nick N.

12. Boyhood (Richard Linklater)

Boyhood is a revolutionary, ambitious masterpiece that frequently resists an episodic structure. A single film that, despite the 12-year duration of production, unfolds simply as life does: there are no transitions, the only clues as to what year we have being Linklater’s subtle soundtrack choices. Haunting in its details, the drama is very simply the story of Mason (Ellar Coltrane) living moment to moment, often moving through Texas with his mother (Patrica Arquette) who hasn’t quite figured things out and his occasionally bratty sister (Lorelei Linklater). Ethan Hawke beautifully plays the wayward father, himself in flux as he matures from musician to actuary. Often Mason does not understand the context of each moment, which is partly why the film’s impact grows more profound upon subsequent viewings. A masterpiece in any year, Boyhood represents, above all, the very best in American independent filmmaking: strong storytelling often presenting conflict or danger as Mason experiments with drugs, drinking, sex, and, ultimately, heartbreak. Leaving him on the same ambiguous note it found him some 12 years and 165 minutes prior, this is a sublime, exhilarating, and emotional cinematic experience, and a new classic. – John F.

11. The Social Network (David Fincher)

Sure, frequent comparisons to Citizen Kane set the bar unfairly high for The Social Network, but this is David Fincher and his collaborators working at the top of their game. Of Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross’ three scores, this one stands tall, and Jeff Cronenworth’s cinematography has never felt so vital. Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall, meanwhile, edit precisely so that the film moves not just between past and present, but also between stasis and movement captures the disparity between big dreams and unfulfilled desires. The cherry on top is Jesse Eisenberg’s cold, calculating performance, which punctuates the film with cruel humor. The Social Network has already proven itself to be remarkably prescient, a prologue for an era in which internet memes pervade everyday conversation even amongst those who have never fashioned themselves “nerds” and which reminds us that smarts and creativity can’t compensate for perceived failed masculinity if, as we are told in the first conversation, you are “an asshole.” – Forrest C.

10. Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen)

Determining the “best” Coen brothers film seems an insurmountable challenge, and certainly a silly one. But everyone has a favorite, and while I adore Lebowski as much as the next dude, Inside Llewyn Davis takes the top spot. The (fictional) setting — 1961 Greenwich Village, Chicago, back to New York — is an ideal playground for the film’s folk singers, poets, jazz musicians, and intellectuals. And in typical Joel and Ethan Coen fashion, there is great humor here. But Llewyn is exhilaratingly bleak, a character study in which the characters are lovably prickly. It is also highly moving, that rare music-based film in which the performances feel earthy and passionate. We leave Llewyn Davis (so memorably embodied by Oscar Isaac) at a familiar low point, and can only guess at his eventual outcome. His uncertain, unsettled fate resonates, and the film seems to have taken on a life of its own. Like the music at the Gaslight, Inside Llewyn Davis stops, but never ends. – Chris S.

9. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s not-quite-Scientology-but-maybe-it-is? epic is his most deliciously obtuse puzzle. The Master is all jagged edges, never quite coalescing into anything recognizable, and that’s part of its charm. What other filmmaker would create film of such mystery? And who else would dare to unleash Joaquin Phoenix in such a way? It is easy to forget now, a few years after release, that this was his first film of the post-I’m Still Here era. It is also easy to forget that, remarkably, Philip Seymour Hoffman did not win a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his muscular, unforgettable performance as Lancaster Dodd, leader of “The Cause.” (Somehow, the work of Christoph Waltz in Django Unchained was deemed stronger.) Today, Phoenix and Anderson are basking in the hazy success of Inherent Vice, Amy Adams is one of the world’s biggest stars, and Hoffman, of course, is no longer with us. For all of these principles, The Master represents a dizzy, unsettling high, and one of the unquestioned triumphs of 2010s cinema. – Chris S.

8. Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami)

Abbas Kiarostami’s first narrative feature outside of Iran broke away from questions of social reality through cinema to ones of artistic representation itself, a Socratic dialogue on theory masked as romantic melodrama in the vein of Rossellini’s Journey To Italy. The early, leisurely discussions between Kiarostami’s casually distanced protagonist (William Shimell) and chameleon vision of desire (Juliette Binoche) morphs into a meticulous waltz of passionate idealism and marital strife, all wrapped up in philosophical questions about observation and creation in a vein of new-media paradoxes placed into both ancient and practical consequences. Every line of dialogue, camera movement, edit, and sudden choice in mise-en-scène makes the spectator a critic, using evaluative measures to participate in the artistic claims being put on trial. But the intellectual operations are dependent on the single tear that continually grounds the pains of romance, a vision of decades of emotion squeezed into a single day. In the end, this walk-and-talk embodies the very nature of cinema’s space for open-ended possibilities — both a window and a frame. – Peter L.

7. Amour (Michael Haneke)

There is a certain indescribable manner through which Michael Haneke is able to lure you into his films that leaves you in a state of both shock and awe. Such is the case with Amour, a heart-wrenching and unflinching portrait of an elderly couple faced with the trials and tribulations of aging. In showcasing the intimate pain of watching someone you love slowly suffer, Haneke takes a departure from his usually emotionally-detached narrative troupes, offering his most humane film to date heart. Amour is an incredible testament to the power of love we have for those closest to our hearts, and a work that forces us to question the very essence of our own livelihood when confronted with the clocks of fate. – Raffi A.

6. The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese)

A few weeks before The Wolf of Wall Street opened, American Hustle came out. While David O. Russell’s film is plenty of fun, it ultimately came off as Scorsese-light when the legendary filmmaker released this expertly directed juggernaut of a movie shortly after. While some complained about its length, that indulgence serves these reprehensible, funny, and scarily human pieces of rich trash. This may be a three-hour movie, but it moves like a bullet. There’s not a dull moment in this wild epic, and Jordan Belfort trying to get to his car while impaired, thanks to the power of ludes, is one of the finest pieces of physical comedy we’ve seen in the 21st century. – Jack G.

5. A Separation (Asghar Farhadi)

Here is a rare “film of the moment” that was as good as every bit of hype suggested. Asghar Farhadi’s fifth feature, his international breakthrough, was almost too good to be true, roving through scene after scene with an eye for every complication that comes with human quarrels and the intelligence to compact this messiness into a narrative that, in being at once deeply relatable and dictated by non-Western customs, made clearer the goings-on of a world many here would consider a threat. As sensitive as it is scathing, as graspable as it is insanely complex. We’re unlikely to see many endeavors that are this powerful in the next five years’ time. – Nick N.

4. Her (Spike Jonze)

Few directors are as adept at making tearjerkers as Spike Jonze. Whether it’s the wild childhood emotions in Where the Wild Things Are or the honest depiction of the creative process, love, and brotherhood in Adaptation, the stories the director tells are always honest and moving, and the same goes for his 2013 love story, Her. There’s such a delicacy to Jonze’s approach, never expressing any judgement towards Theodore’s (Joaquin Phoenix) relationship with Samantha (Scarlett Johansson). When the two have phone sex, the director cuts to black, letting the sound convince you they’re no different than other couples. It’s a beautiful, heartbreaking, and hopeful film about love, breakups, and moving forward. – Jack G.

3. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

If one looks below the surface of the vigorous and relentless style on display in Leos Carax’s Holy Motors, there’s much substance to relish and explore. Carax, following other arresting and fantastical cinematic detours like Lovers on the Bridge and Pola X, creates a fascinating and deliberately schizophrenic portrait of what it is about the movies — both making and viewing them — that attracts us. Carax never settles on one style, on one motif or genre, or even one progressive viewpoint, although at a superficial level the film can be said to follow Denis Levant’s chameleon-like shape-shifter. So many modern films are simply exercises in chasing familiar tropes, while Holy Motors delights in its own idiosyncratic shuffling of what we expect. Below the motion-capture eroticism involving digital monsters, beyond the creepy French leprechaun gobbling his way through Paris, and just to-the-right of the invigorating musical numbers featuring accordions and Kylie Minogue is a very insightful and even poignant look at our own mortality, and the ghosts it causes us to chase. – Nathan B.

2. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer)

Scarlett Johansson has never been better than in Jonathan Glazer‘s visual monster of a film, playing an alien huntress praying on Scottish locals. Deliberately paced and pointedly told, Under The Skin feels like exactly the film Glazer set out to make; a singular vision with a delicate touch filtered through a sci-fi genre narrative. Brilliant from start to finish. – Dan M.

1. The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick)

For his entire career, Terrence Malick has been contending that the divine can be found on Earth. With The Tree of Life, his case was firmly put to rest, with cinematography from Emmanuel Lubezki helping prove it in every vivid frame. The stirring reflection on our place in the universe is book-ended by eloquently orchestrated sequences concerning life’s origins and demise, but its central story ruminates on the journey in-between. And while we specifically follow a family in late-50s Texas, there’s a universality that provides a mirror into timeless questions of significance and meaning that humanity has grappled with for ages. An ethereal odyssey into what came before us, what makes us human, and our certain future, The Tree of Life is an enrapturing testament to the profound beauty of cinema. – Jordan R.

Individual Ballots

15. The Social Network

14. The Illusionist

13. Hanna

12. Attack the Block

11. Take Shelter

10. The Master

9. Looper

8. Django Unchained

7. The Wolf of Wall Street

6. Kill List

5. The Imposter

4. Under the Skin

3. The Guest

2. Room 237

1. Exit Through the Gift Shop

15. Anna Karenina

14. Kid With A Bike

13. Margaret

12. ParaNorman

11. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints

10. To the Wonder

9. Her

8. Melancholia

7. Upstream Color

6. Rust and Bone

5. Shame

4. Beginners

3. Enemy

2. The Grey

1. The Tree of Life

15. Dogtooth

14. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

13. Shame

12. Holy Motors

11. 12 Years a Slave

10. Oslo, August 31

9. The Social Network

8. Blue is the Warmest Color

7. Inside Llewyn Davis

6. The Wolf of Wall Street

5. Drive

4. The Tree of Life

3. The Master

2. Amour

1. Under the Skin

15. Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie

14. The American

13. Exit Through The Gift Shop

12. To The Wonder

11. The Tree of Life

10. Tuesday, After Christmas

9. Oslo, August 31st

8. The Great Gatsby

7. Boyhood

6. Before Midnight

5. Holy Motors

4. Jane Eyre

3. The Deep Blue Sea

2. Ida

1. Under The Skin

15. Prisoners

14. Perfect Sense

13. The Lords of Salem

12. Like Someone in Love

11. Sinister

10. Another Year

9. Tuesday, After Christmas

8. The Mend

7. Twixt

6. Barbara

5. The Deep Blue Sea

4. Keep the Lights On

3. Flight

2. Welcome to New York

1. Don’t Go Breaking My Heart

15. 4:44: Last Day on Earth

14. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

13. The Wolf of Wall Street

12. Cosmopolis

11. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

10. The Tree of Life

9. The Immigrant

8. The Color Wheel

7. Goodbye to Language

6. Lincoln

5. The Strange Case of Angelica

4. Stray Dogs

3. This is Not a Film

2. A Burning Hot Summer

1. Horse Money

15. Hard To Be A God/The Wolf of Wall Street

14. Uncle Boonmee

13. Two Days, One Night

12. The Immigrant

11. You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet

10. Leviathan (2012)

9. Upstream Color

8. Once Upon A Time in Anatolia

7. Meek’s Cutoff

6. A Separation

5. The Social Network

4. Holy Motors

3. Margaret

2. Closed Curtain

1. The Tree of Life

15. Hanna

14. Magic Mike

13. Killer Joe

12. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

11. Drive

10. The Master

9. Moneyball

8. Young Adult

7. The Social Network

6. Greenberg

5. Mud

4. Inherent Vice

3. Inside Llewyn Davis

2. The Wolf of Wall Street

1. Her

15. Oslo, August 31st

14. Short Term 12

13. The Act of Killing

12. The Master

11. We Need to Talk About Kevin

10. Intouchables

9. Upstream Color

8. Whiplash

7. Shame

6. Never Let Me Go

5. Blue Valentine

4. Black Swan

3. Melancholia

2. Her

1. The Tree of Life

15. Mommy

14. Mr. Turner

13. Hugo

12. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

11. Holy Motors

10. This Movie is Broken

9. The Act of Killing

8. Wetlands (2011)

7. Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God

6. Nebraska

5. Another Year

4. At Berkeley

3. Cloud Atlas

2. Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage

1. Boyhood

15. Exit Through the Gift Shop

14. Boyhood

13. To the Wonder

12. The American

11. Dogtooth

10. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

9. The Social Network

8. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

7. Amour

6. Before Midnight

5. A Separation

4. Inherent Vice

3. Martha Marcy May Marlene

2. Inside Llewyn Davis

1. The Tree of Life

15. Cloud Atlas

14. Beasts of the Southern Wild

13. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

12. This Is Not A Film

11. Upstream Color

10. Grand Budapest Hotel

9. Once Upon A Time in Anatolia

8. Mysteries of Lisbon

7. Holy Motors

6. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night

5. Her

4. A Separation

3. Take Shelter

2. Certified Copy

1. The Tree of Life

15. Meek’s Cutoff

14. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

13. Hard to Be a God

12. You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet

11. Stray Dogs / Journey to the West

10. Django Unchained

9. The Immigrant

8. The Wolf of Wall Street

7. Leviathan (2012)

6. Bastards

5. Cosmopolis

4. Moonrise Kingdom

3. A Separation

2. Closed Curtain / This Is Not a Film

1. The Tree of Life

15. Don’t Go Breaking My Heart / Blind Detective

14. Hahaha

13. Sleepless Night (2012)

12. Haywire

11. Dusty Stacks of Mom / Let Your Light Shine

10. Goodbye To Language 3D

9. Amour Fou

8. Margaret

7. Hard To Be A God

6. Leones

5. Moonrise Kingdom

4. Computer Chess

3. Cosmopolis

2. Mysteries of Libson

1. Certified Copy

15. Blue is the Warmest Color

14. 12 Years a Slave

13. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

12. This is Not a Film

11. Boyhood

10. Exit through the Gift Shop

9. Melancholia

8. The Master

7. Certified Copy

6. Goodbye to Language

5. Holy Motors

4. Under the Skin

3. The Turin Horse

2. Enter The Void

1. Amour

Share your favorite films of the decade thus far below.