For our most comprehensive year-end feature we’re providing a cumulative look at The Film Stage’s favorite films of 2021. We’ve asked contributors to compile ten-best lists with five honorable mentions—a selection of those personal lists will be shared in coming days—and from tallied votes has a top 50 been assembled.

So: without further ado, check out our rundown of 2021 below, our ongoing year-end coverage here (including where to stream many of the below picks), and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2022.

50. This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese)

Framed as an epic fable and shot like a myth, Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese’s This is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection is another beautiful, tragic diary entry on the history and people of his home country Lesotho. His focus shifts from the metaphorical relationship of Mother, I am Suffocating, This is My Last Film About You to a physical one, where the modernization and industrialization of the 21st century that has come to thrust and uproot an unsuspecting people from ties to their lands and ancestries. The frame’s earthy, worn textures combine brilliantly with the story of a matriarch making her last stand to preserve a place built with her blood. – Soham G.

49. Nine Days (Edson Oda)

A woman dies. Was it accident or suicide? The compassionate yet strict God-like figure who selected her soul to live is crippled by the uncertainty, wondering if he chose wrong. Was she not strong enough for the world? Was the world too cruel? Are these things simply outside our control? Edson Oda’s beautifully introspective Nine Days positions us to watch the watcher and, in turn, begin understanding our own thoughts on life, regret, and guilt through Will’s (an unforgettable Winston Duke) personal reassessment. He must now choose a replacement despite the raw pain of her loss. This is that process: to utilize his usual criteria or adjust and perhaps exacerbate the issue by holding warm, artistic souls (like hers and his) back. It’s funny and sobering and inspiring. Life’s small, undefinable moments are too precious to be undone by self-enforced absolutes. – Jared M.

48. CODA (Sian Heder)

A crowd-pleaser that unfortunately screened mostly to streaming audiences, Sian Heder’s Sundance-winning CODA is an adaptation of La Famille Bélier set in New England that, along with Netflix’s Deaf U, is a landmark in representation onscreen and off. The story of the Rossi family and their daughter Ruby (Emilia Jones)—the only hearing member (a CODA or Child of Deaf Adult) who aspires to a career in music––who is torn between staying in Gloucester to help with the family business or chase her dreams. Heder’s richly textured film emerges as a portrait of a loving family (played by deaf actors Marlee Matlin, Troy Kostur, and Daniel Durant) who are fiercely independent, rebellious, and supportive as both insiders and outsiders on Massachusetts’ north shore. A smart, perceptive coming-of-age story with nearly no false notes. – John F.

47. Bad Trip (Kitao Sakurai)

The epitome of controlled chaos. Harnessing a manic, psychedelic energy where at any moment he can combust, Eric Andre’s gift is the uncanny ability to lure people into his gravity. Andre manages to weave together a by-the-numbers rom-com plot through a series of hidden-camera pranks as he and Lil Rel Howery hit the road. Bad Trip shows us the random magic of the human experience while also giving us a thrilling comedic ride that acts as a meta-commentary on the nature of filmmaking and rom-com genre. – Erik N.

46. Flee (Jonas Poher Rasmussen)

There have, of course, been a great many animated films about deeply serious subjects—many in recent years, from Persepolis to Anomalisa to Waltz with Bashir. Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee now comfortably fits on this shelf of profoundly affecting films. Indeed, Flee ranks as one of the most uniquely memorable animated films of this last decade: remarkably successful as a study of the refugee experience, as a coming-of-age drama set against a backdrop of fear and danger, and as a tribute to one individual’s ability to survive and even flourish. An extraordinary achievement. – Chris S.

45. Test Pattern (Shatara Michelle Ford)

Written and directed by Shatara Michelle Ford, this stellar feature directorial debut concerns a couple thrown into a Kafka-esque chaos as they attempt to have a rape kit administered. The night before, Renesha (Brittany S. Hall) went out for drinks with a friend and blacked-out after encountering two men at a bar. There is so much here to recommend: long, stressful master shots that elucidate every emotion; lead performances from Hall and Will Brill that barely feel like performing; a spare screenplay that eschews judgment or presumption. Ford is a star and it’s exciting to think how far their career will go. – Dan M.

44. The Tragedy of Macbeth (Joel Coen)

Joel Coen’s take on the Scottish play unfolds almost entirely on sets—sharply angled, streaked with shadows and shards of light. It’s an approach that marries theater’s immediacy with cinema’s narrative drive. More Dreyer than Bergman, more Welles than Olivier, this is the sharpest Shakespeare adaptation in years, a hurtling descent into madness with astonishing performances by Denzel Washington, Frances McDormand, and Kathryn Hunter. Richly layered black-and-white cinematography by Bruno Delbonnel meshes wonderfully with Stefan Dechant’s spiky production design. – Daniel E.

43. Ema (Pablo Larraín)

Pablo Larraín’s dour take on Princess Diana is getting all the attention this year, for better or worse, but it’s his other feature, Ema, that deserves it. The neon-drenched Chilean mountain-town odyssey reveals its winding narrative piece by piece, eventually showing its true form: a thriller love story about experimental dance, autonomy, art, and a regretfully returned adoption. It premiered at Venice in 2019, one of many films that’s been largely forgotten because of its long stay in distribution limbo. But with a sexy reggaeton-centric score by renowned electronica artist Nicolas Jaar and Mariana Di Girolamo’s unforgettable performance, consider it unmissable. – Luke H.

42. The Woman Who Ran (Hong Sangsoo)

In many of Hong Sangsoo’s films, female characters are forced to listen as listless, drunken men endlessly whine about their relationship problems and professional failures. The Woman Who Ran flips the script by focusing its narrative almost entirely on a trio of calm, reflective conversations between women who politely dance around confrontation. Favoring breezy, dialogue-heavy scenes, each segment gets disrupted by a disgruntled man clamoring for underserved respect. But this subtle masterpiece doesn’t dwell on such hurtful distractions. Instead it functions as a loving respite from the exhaustion they produce, as in a beautiful final scene where one character avoids rehashing old heartbreak and ventures back into a movie theater to enjoy the tranquil ending of a film she’s just finished. Sometimes cinema truly is the only escape. – Glenn H.

41. All Light, Everywhere (Theo Anthony)

Theo Anthony’s All Light, Everywhere casts a wider focus than his wholly original debut Rat Film while retaining the same unique vision as he explores how technological breakthroughs (and pitfalls) in filmmaking have reverberated throughout history to both embolden and trick our perceptions of perspective. To thread these strands and see its modern-day effects, his film primarily looks at the engineering behind police body cameras, the extensive use of those devices and other surveillance equipment to support officers in cases where evidence might otherwise come down to only verbal testimonies. Staggering in its expressive yet concise ability to explore a topic as urgent as rampant police violence and excessive surveillance from strictly technological perspectives, All Light forces viewers to question the veracity of everything that crosses their eyes. – Jordan R.

40. Cry Macho (Clint Eastwood)

Clint Eastwood has made films about the elegiac decay of the cowboy for decades. He is a filmmaker fixated on ideas of his own mortality, using work to convey his regrets in life and create final images that will hopefully define his legacy. But Cry Macho represents a new spin on films such as Honkytonk Man and The Mule, accepting that the best way to leave legacies isn’t through martyrdom, but making gentle connections with those who stay behind. It could easily be seen as minor, but after a lifetime of adrenaline it’s wonderful seeing the final cowboy enjoy a dance and raise a chicken while he still can. – Logan K.

39. Passing (Rebecca Hall)

A triumph of a directorial debut. With a strong command of multiple cinematic tools, Rebecca Hall (adapting Nella Larsen’s novel) creates a film that, like its main characters, plays along the edges of nuance and ambiguity. Its striking black-and-white cinematography tells a clever story about color, obscuring or emphasizing Irene’s (Tessa Thompson) and Clare’s (Ruth Negga) skin tones as the scene demands, allowing them to move between Black Harlem or white Manhattanite society as they wish. But though they have much in common, Irene and Clare are nearly exact opposite sides of the same coin. They challenge, love, and envy each other all at once, and from this relationship of paradoxes Hall draws out an engrossing drama about the intersections between race, class, gender, and desire. Passing is finally not about whether Irene and Clare pass; it’s about the consequences of when they do. – Jonah W.

38. Slow Machine (Paul Felten and Joe DeNardo)

A Swedish experimental-theater actress flees an ambiguously predatory friendship with an NYPD Intelligence agent, crashes at the upstate home where Eleanor Friedberger is rehearsing with her band, and deflects toxic alpha and beta masculinity with a Texan cover story and accent, feeding into a prevalent, ominous vibe of role-playing and surveillance. Shot on beautiful, blotchy 16mm, Paul Felten and Joe DeNardo’s debut surfaces a New York bohemia—scattered across far-flung windowless apartments, steeped until funky in radical narrative and political theory—that still feels underrepresented onscreen. It elides the difference between creative-class caginess and security-state menace, with a self-cameoing Chloë Sevigny delivering a metaphysical audition monologue that nails down an overall tone of ambient hostility. (Which, thanks to the sharpened and polished dialogue, is consistently hilarious, like stage combat with real swords.) – Mark A.

37. Wife of a Spy (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Once you groove on its hazy (let’s say “dreamlike”) cinematography, the 50th-or-so confirmation of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s mastery—of form where every shot necessitates its place as it commands focus, of narrative where every revelation (co-scripted by Ryūsuke Hamaguchi) comes precisely as the film demands. But also at a baseline level of craft destined to earn nice-enough responses for now; check back in however-many years when it’s understood as a classic. – Nick N.

36. The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson)

Just when we think Wes Anderson’s exhausted his quirky, colorful, dry, indie extravaganza filmmaking style, he proves us wrong—again. The French Dispatch sees Anderson employing new tricks as confidently and creatively as he does his old favorites. The star-heavy film takes us ceremoniously through the last issue of “The French Dispatch” via three separate stories told by their respective writers (Tilda Swinton, Frances McDormand, Jeffrey Wright). Nearly every shot a masterfully considered feat, all very hard to look away from. – Luke H.

35. Shiva Baby (Emma Seligman)

All bets are off the moment Danielle (a star-making turn from Rachel Sennott) realizes she doesn’t know whose shiva she’s walking into. If she doesn’t know that, how can she begin preparing for its potential guests? Emma Seligman’s hilarious Shiva Baby is as much a dark comedy in the vein of Death at a Funeral as it is a nightmarish 77-minute panic attack. Danielle tries avoiding confrontation as often as she inevitably seeks it out to push boundaries or escape the uncertainty of what might happen when she doesn’t (with Polly Draper and Molly Gordon hovering as mother and ex, respectively). It’s a whirlwind journey towards clarifying and accepting her own personal truth while enduring the emotional, psychological, and physical duress born from avoiding it. Will embarrassment allow Danielle’s secrets to control her? Or will she recognize their inherent power before taking control instead? – Jared M.

34. The Green Knight (David Lowery)

Stealthily 2021’s far more nuanced interpretation of humanity’s losing battle against the whims of the environment, David Lowery’s take on the classic Arthurian poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is severe yet spellbinding—cryptic, decadent, and surprisingly erotic. Dev Patel slides into one of this year’s most salacious roles as the floppy-haired Gawain on a quest to return the blow he landed on Ralph Ineson’s Green Knight one year prior. Underneath the medieval folktale simmers a modern allegory for misplaced faith, no match against a friendly foe that can retaliate tenfold against humankind’s destruction. – Brianna Z.

33. Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar (Josh Greenbaum)

Though some have dismissed Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar as an extended SNL bit, it’s precisely this commitment to the bit (or, rather, numerous bits) that makes the film so endearing. Every scene in the Annie Mumolo- and Kristen Wiig-scripted film about two middle-aged women in culottes on vacation is designed to send another ten jokes flying your way. Your mileage may vary from your sense of humor, but there isn’t a single comedy this year that’s as stylish, silly, and surprisingly sensitive as this one. – Juan B.

32. Mass (Fran Kranz)

Fran Kranz, not only an experienced actor but also a noted theater director, brings vulnerability from the stage to his debut film Mass. By entrapping the audience, much like the four victims of grief at the center, he takes advantage of the medium with heartbreaking close-ups. With every movement and monologue due reverence is given for this sensitive topic of ever-present threats of gun violence in American schools. In grappling with the aftermath and characters’ desperation, a catharsis is formed by meeting together—a sense of closure that is wholly irrevocable and directed with a deft touch by Kranz, a new voice in American cinema we look forward to seeing blossom. – Margaret R.

31. Quo vadis, Aida? (Jasmila Zbanic)

One of the most moving and harrowing films of the year, Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida? reenacts the horrific Bosnian genocide through the eyes of a UN translator stuck between the powerful officials calling the shots and the vulnerable townspeople to whom she belongs. A fascinating study of power and complicity that never glorifies violence, instead training an accusing lens on those who wield power to hurt others. – Orla S.

30. Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (Radu Jude)

After a sex tape is released online, a schoolteacher (Katia Pascariu) goes on an odyssey through sunny Bucharest. She later faces a kangaroo court made up of her colleagues and peers. In the middle many other things happen. Combining narrative and archival filmmaking with elements of theatre, political allegory, memes, and satire, Radu Jude—perhaps the most idiosyncratic filmmaker to emerge from the Romanian New Wave—created one of the strangest, most singular films of the year in Bad Luck Banging or Looney Porn. It also won the director a Golden Bear, an acknowledgement as overdue as it was richly deserved. – Rory O.

29. C’mon C’mon (Mike Mills)

With its NPR-style milieu and what can be anathema for critics––a deeply sentimental story about loss and forgiveness––Mike Mills’ C’mon C’mon overcomes the odds. As in his script, honesty and decency somehow prevail, aided by Woody Norman’s unfussy work as nine-year-old Jesse and Robbie Ryan’s intimate, meticulous cinematography. C’mon C’mon dares you to hate it, knowing just how hard it is to turn away from a grieving child. – Daniel E.

28. Benedetta (Paul Verhoeven)

Paul Verhoeven’s latest is both an irreligious film and one with sincere conception of the sacred, mischievously owning the contradiction. Stripped of budgetary largesse, and even some of the prestige imparted by Isabelle Huppert and the bougie French setting of Elle, the Dutch master comes up with one of his bluntest, most aggressive broadsides against institutional corruption and power. Verhoeven stares down the Catholic Church and Holy Roman Empire whilst venerating yet another strong woman in the mystic Benedetta Carlini (Virginie Efira). The director’s own personal Jesus, she’s an apex predator in––to quote Jacques Rivette’s praise of Showgirls––a “world populated by assholes.” – David K.

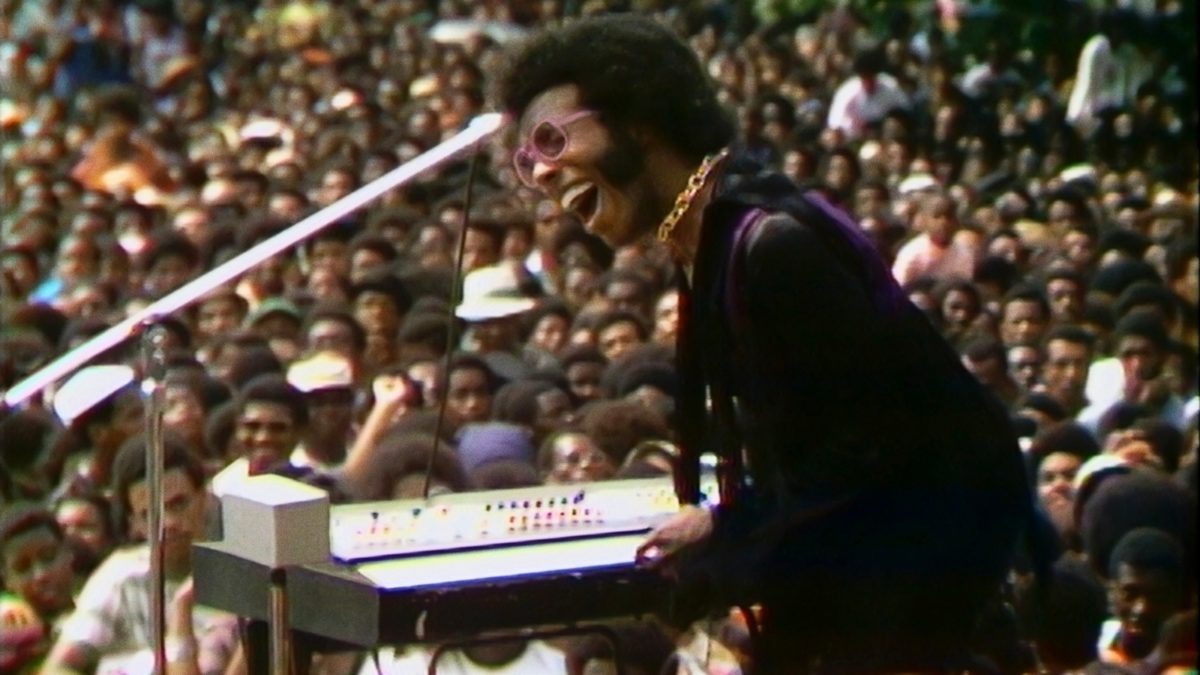

27. Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Amir “Questlove” Thompson)

Both an act of discovery and rectification of history, Summer of Soul revives and restores an explosion of musical talent and collective memory. In his directorial debut, Amir “Questlove” Thompson expertly cuts together pristine, previously forgotten footage from the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, a free outdoor concert series that attracted 300,000 people and featured the best gospel, blues, and R&B singers alive. Beyond showcasing the festival’s stars, Thompson navigates the intersection of the country’s racial and social revolutions, letting marginalized voices do all the talking while Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone and Mavis Staples (to name a few) do all the preaching. It’s groovy, powerful bliss. – Jake K.S.

26. The Beatles: Get Back (Peter Jackson)

The greatest gift a music or history lover can receive, Peter Jackson’s three-part, eight-hour documentary is a Frankensteining of all the footage captured of the Beatles developing Let It Be, the penultimate album they recorded and final they released. For those in love with the four lads from Liverpool, every second is a treasure. It’s wild to have this kind of access, to witness one of the biggest moments in music (and cultural) history so clearly, so comprehensively. To see how the Beatles shaped songs, came up with lyrics, messed around in the studio, got frustrated with each other, or allowed creative input from others. To see how much they still loved each other at the end, but how truly they felt pulled in their own directions. To cap the blissful experience, Jackson sends us off with the full Apple studios rooftop concert, the last live show the Beatles ever played together—an indelible delight. – Luke H.

25. Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon A Time (Hideaki Anno)

A reclamation project and a chance to forge a new path forward, this is Hideaki Anno’s most significant and impressive film since End of Evangelion, the movie this film essentially abridges. Evangelion has always rooted itself in Anno’s difficult upbringing, and he carries his trauma into his art as a way to find hope amidst chaos. Though redoing something you’ve already done is often a futile endeavor, Anno is so in tune with the fabric of this series that transporting it into a new century, for a new generation comes naturally. If it was a rocky road reaching the end of the Eva Rebuild, this masterpiece justifies all. – Soham G.

24. What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? (Aleksandre Koberidze)

It’s not hyperbolic to suggest Alexandre Koberidze’s sophomore effort is one of the most original, alive, astonishing films to come around in years. A young Georgian couple meets cute only to have their romantic plans derailed after each wakes up the next morning looking like completely different people. The mysterious, affecting dual journey that unfolds is lovingly indebted to the rhythms and grace notes of silent cinema, the city symphony, romantic comedy, and work of Manoel de Oliveira. Ultimately, Koberidze’s all-timer proves there’s room for kindness and narrative reinvention in the face of a brutal world, “because everything happened the way it had to happen.” – Glenn H.

23. Zeros and Ones (Abel Ferrara)

There will never, ever be need to make the definitive COVID movie, and surely Abel Ferrara—who I once saw respond to an over-involved question with “yeah we all saw the movie bro”—would take my claim with, at best, a shrug and grunt. But nothing’s so transposed the sensations of being alive in spring 2020—wandering empty streets that make you feel like the last man alive, every meet-up with friends carrying the air of a clandestine operation, failing to compartmentalize bits and pieces of information from a phone—and especially nothing’s translated them to a narrative focused elsewhere. Maybe elsewhere. I remain uncertain what actually happened in Zeros and Ones, notwithstanding memory of the Vatican (?) blowing up and Ethan Hawke’s twin brother screaming patriotic agitprop. Who cares: a new classic, and already evidently one of the greatest films from a great American artist. – Nick N.

22. In the Heights (Jon M. Chu)

Arriving on the scene at the optimistic part of the year (Hot Vax Summer), Jon M. Chu’s In the Heights is one of the best musicals from a year with several good ones. A colorful celebration of life in Washington Heights, the story is led by Anthony Ramos’ Usnavi, a bodega owner with dreams of returning to a romanticized version of the Dominican Republic, though he later comes to realize the island of your dreams is where you make it. Adapted from Lin-Manuel Miranda’s award-winning play, the film isn’t simply a love letter to New York but also one that addresses multicultural tensions, gentrification, and community building in a far more sophisticated way than either West Side Story. It feels both intimate and large, a celebration of hot summer days, hard work, and the encounters people have when they live in neighborhoods, not heroically sealed high-rises. Chu never misses a beat, from the opening showstopper that celebrates the simple act of getting up and going to work in the city to a joyful Busby Berkeley homage in a public swimming pool on the hottest day of the year, while more intimate, gravity-defying numbers take place when time seems to stand still. In the Heights is a dazzling, masterfully crafted film that came just when we needed it. – John F.

21. The Matrix Resurrections (Lana Wachowski)

Much has been made about the ways Lana Wachowski has used the resurrection of Neo and Trinity to cope with intense grief in her life, using fiction as a way to give her what reality cannot and never will. Just as resonant is the relationship between Keanu Reeves and his character Neo—the actor endured a similar trauma in his life, losing his newborn daughter and partner within a couple years of each other. His arc as Neo holds new weight: both actor and character reckon with the possibility of getting a second chance with a loved one who has left this world, Neo making the choice to break fabrics of reality itself to see someone’s face again. The Matrix Resurrections functions as an act of healing for both actor and director, but also anybody who’s lost someone and would do anything to see them again. A bold, romantic, vulnerable, stunningly ambitious blockbuster. – Logan K.

20. The Last Duel (Ridley Scott)

The Last Duel is an incisive, biting reminder of the grotesque ways in which every pillar of society works in service of the patriarchy. The film’s Rashômon-esque accounts of the rivalry and rape at its center serve not to dispute the victim’s accuracy, but highlight how men attempt to rationalize such horrors and command the narrative. Somehow, Scott juggles tones menacing and playful with a cast in peak form, including an awe-inspiring Jodie Comer and delightfully hammy Ben Affleck. All of which culminates in one of the more brutal action set pieces in recent memory—the capstone on a perfectly crafted, nuanced piece of entertainment. – Conor O.

19. Parallel Mothers (Pedro Almodóvar)

The oft-operatic Pedro Almodóvar composed an utterly tender chamber piece with Parallel Mothers, a film that defies the Spanish master’s usual scope by becoming a lullaby of sorts whispered by Penélope Cruz’s Janis, a photographer who will do anything to keep her infant from being taken away. Pedro and Pé explore the meaning of motherhood by contrasting it with the pain felt by their mother, Spain, as it continues mourning the loss of many children taken by Franco’s dictatorship—children whose mothers will never get to embrace again. – Jose S.

18. Undine (Christian Petzold)

In 2018 Christian Petzold’s masterful Transit took a story from World War II and dropped it in modern-day Marseille, a bold conceit that felt like watching ghosts of the past echo through the present. With Undine, Petzold continues merging old and new to add layers of complexity to his storytelling. The Berlin-set Undine reunites Transit‘s Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski in a tale loosely based on the myth of the water nymph (known most famously through the story of the Rusalka and the Little Mermaid), playing out this time as a tragic romance between a historian and a diver. Much like Transit‘s straddling of period piece and modern-day ghost story, Undine establishes itself in a setting of constant upheaval and transition, with Beer’s historian focused heavily on the ever-changing urban development of Berlin over the centuries. It’s through this approach that Petzold’s grounded direction takes surprising turns, fashioning a basic setup of two people falling in love (a bit of romcom slapstick thrown in for good measure) and making from it a swooning, fantastical romance. – C.J. P.

17. Spencer (Pablo Larraín)

Over the course of his diverse filmography, Pablo Larraín has become the reigning raconteur of public figures wrestling with the constraints of their public image, and of women who refuse to fit into society’s easy definitions. Spencer is a marriage of both impulses in glorious form. Kristen Stewart delivers a career-best performance, disappearing completely into the role and bringing forth a Diana Spencer we’ve rarely seen before. She plays every moment with such raw ache and gravity that it completely dominates each frame, steals every scene she’s in. Around Stewart’s stunning performance Larraín deftly mingles dream sequences and reality, weaving us an unforgettable vision of someone trapped in a nightmarish version of a fairy tale and fighting with everything she has to find her way back to herself. – Jonah W.

16. Titane (Julia Ducournau)

You could fill the length of a hundred firetrucks scribbling out words on Julia Ducournau’s body horror meets dark comedy meets homoerotic rave movie meets about a thousand other things, each of them as fascinating and fully realized as the last. Titane morphs and evolves through myriad themes across its runtime, but the aspect I find myself returning to most is how Ducournau shatters conventional understandings of gender, ripping open these societal boxes we’ve been placed in to tackle questions about what’s masculine, what’s feminine, and what those words even mean to begin with. Through her body horror, she destroys the flesh to remove those ingrained stereotypes and reveal something entirely new in the process. Watching Titane as a non-binary person myself, it tapped into how I see the world in a way no other film has done before, making me feel truly seen and validated. Such a rare, beautiful gift to have. – Mitchell B.

15. Bergman Island (Mia Hansen-Løve)

Mia Hansen-Løve’s Bergman Island is quite transparently a form of self-portrait: it’s about a filmmaker, played by the great Vicky Krieps, in a relationship with another filmmaker, just as Hansen-Løve was with Olivier Assayas. But much more than that. It’s a film about the pains of making personal art, but also its release as a way to reexamine times gone by. Bergman isn’t so much an influence on the film as he is a looming shadow for Krieps’s character, who seeks another―perhaps quieter, more optimistic, less extractive―way of making movies than the Swedish legend. – Orla S.

14. Dune (Denis Villeneuve)

A lot rode on the success of Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi touchstone—long-awaited, and a tentpole release after a torrid pandemic-hit summer for theaters. Could Dune entice cinemagoers back, even as it competed with a simultaneous release on HBO Max? Not just a film that proved there’s life for multiplexes in a COVID world, the Timothée Chalamet-led space epic also showed Hollywood could still produce and excel at brainy blockbusters with operatic visuals, ear-bursting sound—courtesy Hans Zimmer’s hypnotic score—and a diverse ensemble bringing its A-game. Thankfully enough of us saw it on the big screen—Warner Bros. has greenlit part two for 2023. – Ed F.

13. Petite Maman (Céline Sciamma)

Its fantastical premise notwithstanding, Céline Sciamma’s time-traveling tale is a feat of humanist filmmaking rooted in the realest, purest emotions. In Petite Maman‘s depiction of a young mind trying to make sense of life’s many mysteries it glows with insights about growing up and letting go. With such poignant writing that renders any special effects unnecessary, it also reminds you that ultimately we crave magic not to unlock multiverses, but just be able to see someone once again, to say goodbye. A profoundly moving, pint-sized marvel. – Zhou-Ning Su

12. Days (Tsai Ming-liang)

Has any living actor given more of themselves than Lee Kang-sheng? A three-decade corpus with Tsai Ming-liang doubles as a chronicle of his own: youthful and spry in Rebels of the Neon God; unbearably tortured in The River; sexually voracious in The Wayward Cloud; pushed to its breaking points in the Walker series; and by the point of Days simply weathered from time. Lee is that rare actor to convey worlds of feeling in a wide shot and flash microscopic, immediate response with an intense peer into his eyes. His body is the instrument, Days another of its masterpieces. – Nick N.

11. The Souvenir Part II (Joanna Hogg)

When Joanna Hogg released her meditative bildungsroman The Souvenir, inspired by her own young adulthood attending film school and falling in love, she captured the indelible feeling many burgeoning artists have gone through: one of isolation and vulnerability, masterfully conveyed by Hogg’s author avatar Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne). The structurally ambitious yet still personal Part II is the metamorphosis of these feelings into a passion to create. Hogg conveys that in order to live we must tell stories, if only to show that we are never truly alone in this world. It’s a masterful duology destined to be adored by artists and audiences alike. – Margaret R.

10. Annette (Leos Carax)

High-wire tweeness and lacerating barbs in full effect, Leos Carax and Sparks’ wackadoodle rock-pop opera is a balancing act for the ages. I must admit that after seeing the film I had to ask my viewing group if it’s possible Carax was using Annette to admit that he murdered his former love Yekaterina Golubeva; and we also hummed the best songs. Maybe it’s just me, but that’s the mark of a film to last a long time. – Ethan V.

9. Red Rocket (Sean Baker)

Few directors on the planet are making films that feel as lived-in as Sean Baker. Perhaps that is why Tangerine, The Florida Project, and Red Rocket resonate so strongly. More than verisimilitude, though, it is Baker’s understanding of the complexities of human nature that pushes his work to the level of excellence. Simon Rex’s Mikey Saber, an ex-porn star whose eye for a hustle is ever-present, behaves exactly how he should—uncaringly destructive to himself and others, but with a lovable grin. Part of the joy we derive from watching Red Rocket is our realization that Mikey is going to make the selfish move every single damn time. So very, very wrong; so very, very 2021. It cements Baker as one of cinema’s brightest lights, and features a lead performance that remains endearing even when Mikey is at his worst, not to mention a magnificent debut from Suzanna Son. In its final sequence, Rocket reveals Mikey to be something rare: a character completely true to himself. Deluded, but true. Thus Red Rocket is more than a comedy. It is a modern classic exploring the flaws and desires of a man who in his relentless selfishness and overwhelming confidence is a quintessential American. Might sound crazy, but it ain’t no lie. – Chris S.

8. The Card Counter (Paul Schrader)

In this late period of a nearly 50-year career, Paul Schrader continues delivering some of his most vital work. After First Reformed grappled with climate anxiety and corporate greed, his latest “God’s Lonely Man” character study is a prickly War on Terror postmortem, its secretive central figure (Oscar Isaac’s William Tell) a stand-in for a country determined to repeat past atrocities. The Card Counter is one of the year’s angriest works, and one of its best––though I still can’t quite fathom how a film as scathing in its worldview found its way onto Barack Obama’s list of 2021 favorites. – Alistair R.

7. West Side Story (Steven Spielberg)

Leave it to the master. We didn’t need a remake of a classic; we didn’t really want a remake of a classic. And yet. Steven Spielberg’s long-in-the-making re-interpretation of West Side Story is his best film in a decade, arguably the best by anyone this year. Lush color, vibrant sets, and more star-making performances than you could count on one hand, this thing bristles with life. Janusz Kaminski shoots the film like he’s trying to get out of the way of Justin Peck’s beautiful choreography. At once an ode to the original film and a blistering new adaptation, West Side Story is a marvel. – Dan M.

6. Licorice Pizza (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s disheveled period story of the quasi-romantic friendship between precocious 15-year-old Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) and immature, floundering 25-year-old Alana Kane (Alana Haim) brings the LA native back to his sun-kissed San Fernando roots. Hoffman and Haim, in their feature debuts, not only lead this film untethered to a big-name actor, but carry it with the ease of seasoned performers. Licorice Pizza is less a standard love story than a lyrical portrait of the thin, fragile line between adolescence and adulthood; of two people with one foot in one world and one foot in the other, intertwining somewhere in the middle at the most imperfect time. – Brianna Z.

5. The Worst Person in the World (Joachim Trier)

Opening on a golden shot of Oslo, with Cannes Best Actress winner Renate Reinsve filling the center of the screen as late-20s Julie, Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World thrives on the messiness of young adulthood. Trier finds understanding within moments of overwhelming feeling, impulsion brought on by the idea of stasis—a criminal idea to those, like Julie, who don’t have it all figured out. The Norwegian director celebrates that chaos. Her love burns bright and burns out, sequences of time stopping and hallucinogenic trips—along with naturalistic chapters watching the passing moments within someone’s life, like a weekend getaway, work party, or parent’s inaction. A world-class Reinsve holds it all together with some help from an outstanding Anders Danielsen Lie, bringing lightness and solemnity to every breath, balancing this romantic comedy with a genuine, reflective performance amidst Trier’s most accessible work. – Michael F.

4. Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Where else if not Colombia could Apichatpong Weerasethakul set his first film outside native Thailand? The land that birthed magical realism looks eerily familiar in Memoria, bristling with the same otherworldly beauty that made the director’s Thai works dance between real and supernatural. As its predecessors, Memoria mines the subterranean; fueling Tilda Swinton’s quest to understand the mystery behind an ominous thud haunting her voyage through the Andes is an interest in memories, their suppression and excavation. Unmoored from any semblance of plot and unspooling instead as a collection of incandescent vignettes, each its own micro-film, it’s a quietly disquieting meditation where long, static takes double as rooms you can wander into at your own pace. A film that embeds you so successfully in its reverie that stepping out of it can leave you as unsettled as nourished. – Leonardo G.

3. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Ryūsuke Hamaguchi)

Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s first masterpiece of the year, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, is an endlessly playful and inventive triptych. Exploring the thorniness of love, sparks of connection, and mistaken identities across three stunning vignettes, Hamaguchi’s skill at writing dialogue that is as entertaining as it is moving has never been sharper. On any given day my preferred of the three shorts changes, but there’s certainly no funnier or surprising sequence in cinema this year than revenge gone awry between Nao (Mori Katsuki) and Professor Segawa (Shibukawa Kiyohiko). – Jordan R.

2. The Power of the Dog (Jane Campion)

Jane Campion works at the nexus between sex, power, creativity, and misogyny. With the tense but delicate period western The Power of the Dog, her first feature since 2009, she examines a chilling sort of love quadrangle. We’re introduced to Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch), a taciturn and closeted rancher haunted by the memory of a cowboy who groomed him long ago. Isolated but abusive, he clings to––and denigrates––his quietly empathic brother George (Jesse Plemons). But when George marries a humble widow (Kirsten Dunst), threatening the sanctum of their Montana manse, Phil wages psychological warfare against the woman and her effeminate teenage son (Kodi Smit- McPhee). With assistance from cinematographer Ari Wegner and composer Jonny Greenwood, Campion asks us to question the nature of villainy. Her images are at once soft and smoldering, fearful and visceral. Always wear your gloves. – Robyn B.

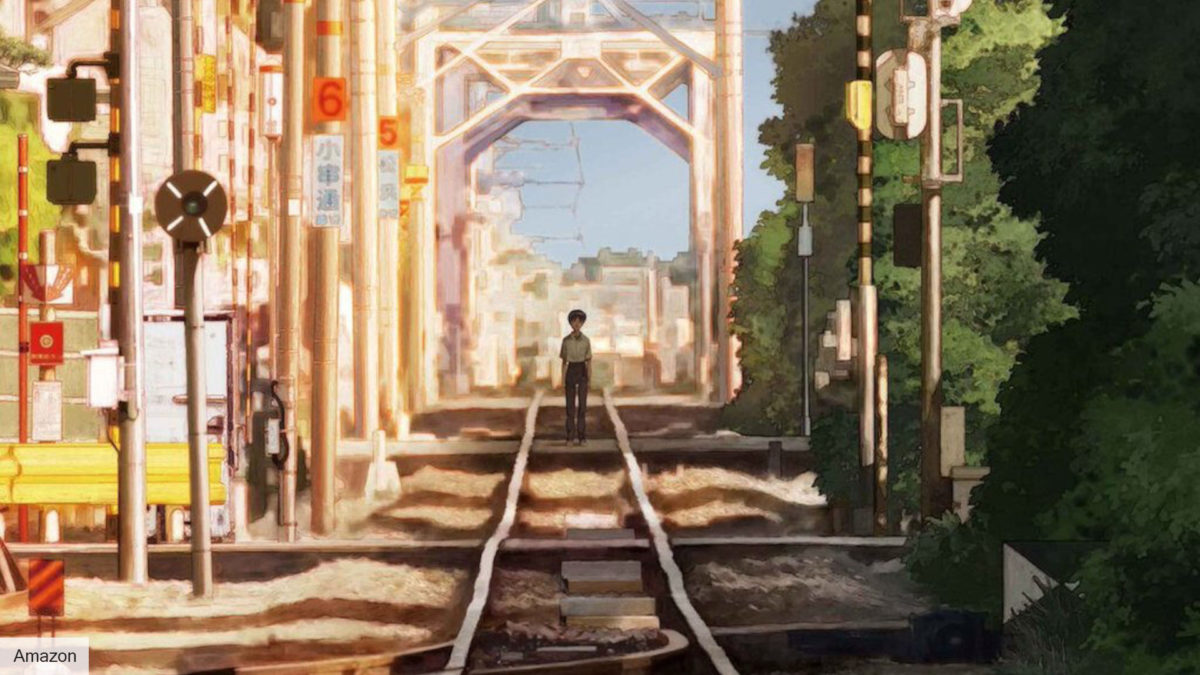

1. Drive My Car (Ryūsuke Hamaguchi)

A totally bewitching, irreducible film, Drive My Car accumulates its overwhelming emotional weight from innumerable elements: the ever-shifting visage of Hidetoshi Nishijima; the stoic intimacy of Tōko Miura; the revolving supporting cast, each figure more distinct and transfixing than the last; the relaxed counterpoint of Eiko Ishibashi’s score. What Ryūsuke Hamaguchi has done here is nothing short of miraculous, a synthesis of all these elements to create something both supremely cathartic and continually tantalizing, fully delivering on its particular narrative throughlines while capturing all manner of mysterious routes that constantly move into the great unknown. – Ryan S.