For our most comprehensive year-end feature we’re providing a cumulative look at The Film Stage’s favorite films of 2022. We’ve asked contributors to compile ten-best lists with five honorable mentions—a selection of those personal lists will be shared in coming days—and from tallied votes has a top 50 been assembled.

Without further ado, check out our rundown of 2022 below, our ongoing year-end coverage here (including where to stream many of the below picks), and return in the coming weeks as we look towards 2023.

50. A Night of Knowing Nothing (Payal Kapadia)

Payal Kapadia’s breakthrough work is a quasi-documentary with something of Chris Marker’s postmodern essay films, following a young film school student, “L,” who experiences a romantic and political coming-of-age amidst the anti-democratic changes wrought in Modi’s India. Yet it boldly eschews the informational and concrete approach of many political documentaries, allowing us a filmic portal into L’s growing consciousness—where “knowing nothing” is not ignorance, only a symbol of intellectual openness. – David K.

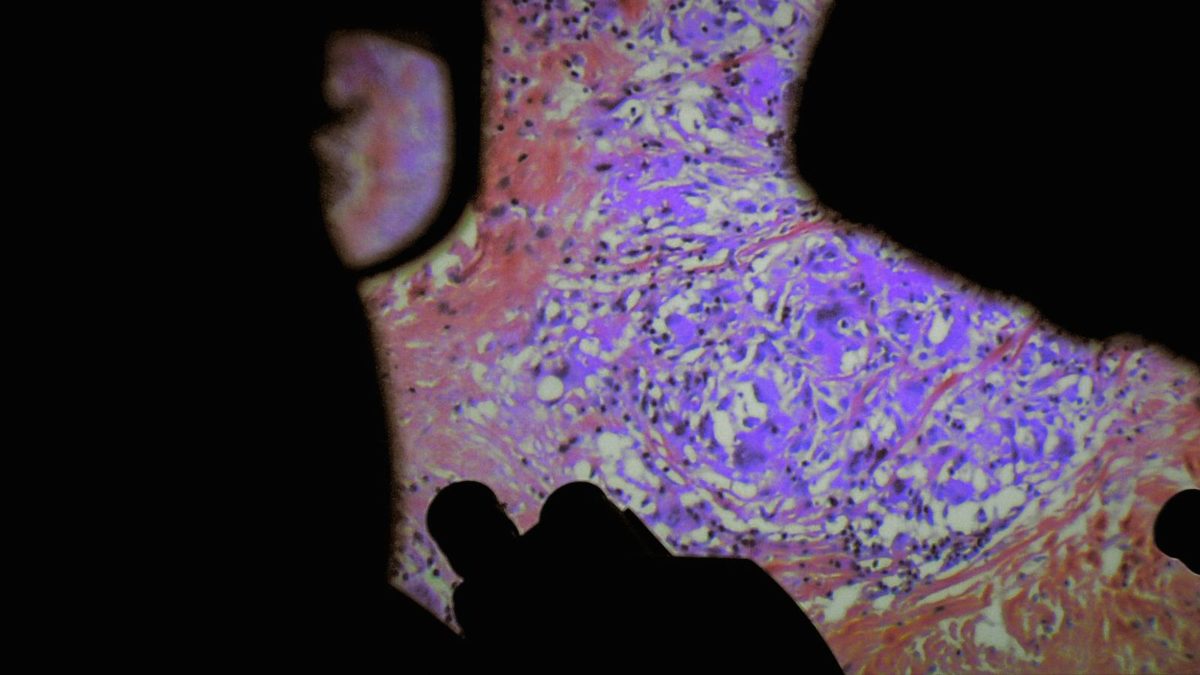

49. De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Paravel)

A surgeon has a pleasant conversation with his patient. The camera pans up and we see the surgeon drilling screws into the man’s skull. Instruments are cutting and cleaning some internal organ. We then see it’s a man’s penis, which squirts out blood. If you’re not used to Verena Pavarel and Lucian Castaing-Taylor’s uniquely visceral style of documentary, this would be a bold first watch. De Humani Corporis Fabrica continues the duo’s masterful partnership in putting cameras where no one else has, yielding imagery no else has found, and turning it into a symphony of the human experience. – Soham G.

48. Living (Oliver Hermanus)

Bill Nighy’s Williams finds a reason to live as the inevitable end approaches in this deeply moving retelling of Kurosawa’s Ikiru, transported to an emotionally repressed postwar London. Like its main character, this is an unfussy, unsentimental film, yet makes an extraordinary emotional mark, powered by a brilliant, nuanced screenplay from Kazuo Ishiguro and Nighy reaching the pinnacle of his career. At a time when we’re all recovering from the trauma of the pandemic, few films in recent years show how precious our time on this planet can be. – Ed F.

47. Magic Spot (Charles Roxburgh)

The world’s most prolific songwriter and filmmaker, Matt Farley, has made another timeless collaboration with longtime director Charles Roxborough. Magic Spot surrounds a rock that can transport people through time, and our hero, Walter (Farley), must utilize the tricky rock to save his deceased uncle and a date with his love interest. In true Farley / Roxborough fashion, Magic Spot weaves low-budget charm and narrative ingenuity into a unique, sweet, hilarious film unlike any other. – Brianna Z.

46. Fabian: Going to the Dogs (Dominik Graf)

A whirlwind romance set in 1930s Berlin, Dominik Graf’s Fabian: Going to the Dogs dives headfirst into the life of its title character, a moralist who finds himself surrounded by the era’s freewheeling debauchery. Graf crams his film with as much hyperactive energy as his young, idealistic characters, making it all the more tragic when they collide with the rise of fascism in Germany. It’s an epic ode to a doomed generation, one that had the world in front of them before it was cruelly taken away. – C.J. P.

45. Three Thousand Years of Longing (George Miller)

Everyone carries stories within themselves––stories that haved shaped for generations. George Miller has unmasked the power of these grand stories in his breathtakingly transcendent passion project Three Thousand Years of Longing. How rare and wonderfully thrilling to see an auteur craft a whimsical, cautious tale inspired by the mythopoetic films of maverick filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Passolini and Michael Powell. His own take on the myths and stories that have formed our world also makes us question what we all truly desire, with Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba giving career-best performances in this future cult classic. – Margaret R.

44. Both Sides of the Blade (Claire Denis)

While her two features this year weren’t initially embraced, I imagine time will be kind to Claire Denis’ nakedly emotional, bruising portraits of fractured relationships, Stars at Noon and Both Sides of the Blade. The latter, shot during lockdown, acted as a reunion with many of her past collaborators and that close-knit nature is felt in every frame of this furious melodrama. Led by Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon as a couple whose relationship is disrupted when an old flame (Grégoire Colin) returns, Denis perfectly calibrates each scene with the ideal note of heightened emotion and immense textural feeling so that, when the emotional climax is reached in verbally explosive fashion, the effect is overwhelming. – Jordan R.

43. No Bears (Jafar Panahi)

It begins twice, all in the same shot. A couple wandering the streets of Turkey learns that only one of them can safely emigrate to Europe; meanwhile, Jafar Panahi directs them remotely from across the (physical and digital) border, working surreptitiously in a small Iranian village to avoid government interference. He’s acting too––reprising his role as himself––yet the danger is real, just as it has been for every project Panahi has undertaken since his state-mandated ban from filmmaking in 2010. The circumstances of No Bears’ production render it a compelling political object, though it is equally compelling as a film. Its pervasive sense of unease, already present at the outset, only mounts as the villagers gradually turn against Panahi, their actions replicating state oppression in miniature. Even thornier, though, is the film-within-a-film, which forces its participants to confront head-on the dangers of protest art and the ethical snags of docufiction. Few directors are so qualified to reckon with their own work, and it’s heartening that said work is as vital and searing as ever. – Cole K.

42. Turning Red (Domee Shi)

Never did I imagine Disney, an Infantilism-Industrial Complex all unto itself, would ever produce a film metaphorizing periods. But here we are. Domee Shi’s Turning Red is the funniest Pixar comedy in a decade and centers on Mei Lee, a Chinese-Canadian tween living in 2002 Toronto. As Mei inches toward puberty––obsessing over boy bands, sketching eroticized mer-dudes––she discovers that all the women in her family are destined to poof into giant red pandas at their first flush of anger unless they learn how to control it. Deliciously, Mei learns to weaponize this new gift to her social advantage. Relying on rapid editing, a warm, vibrant palette, and hilariously manic sight gags paying homage to anime and Looney Tunes alike, Turning Red’s visual style intentionally deviates from Pixar’s more typical dignified grandiosity. This is puberty, baby. – Robyn B.

41. Marcel the Shell with Shoes On (Dean Fleischer-Camp)

Dean Fleischer-Camp’s Marcel the Shell with Shoes On expands on his and Jenny Slate’s (co-writer and Marcel) short film from over a decade prior. It’s a sweet film, never saccharine, always grounded by the smallness of life, in which everyday existence’s mundanity becomes magical. Alongside this sweetness is the overwhelming nature of loss, as Marcel continues living without his friends and family. A single-eyed shell that speaks in simplicity, Marcel becomes a figure to reflect your own insecurities, your own grief, your own frustrations onto. Fleischer-Camp and Slate create an aura of warmth, a world aesthetically not dissimilar to our own that’s opportunity-rich, loving towards neighbors and strangers alike. It might come as a necessary change in perspective, an immeasurable level of hope. – Michael F.

40. Friends and Strangers (James Vaughan)

Rare is the prospect of an Australian comedy. But within two minutes it becomes clear James Vaughn’s feature (his first) must be followed through: images of metropolitan life composed like Heinz Emigholz, willingly stilted performances, vaguely threatening vibe. Progressively the thing grows funnier, its direction harder to guess, structure slightly bewildering yet fully determined. By film’s end Friends and Strangers is plainly fucking hilarious, teetering on possibilities of violent outburst while conveying wise ideas of personal misdirection. I saw this movie nearly two years ago and think about it more than almost any I watched last month; all it took was those two minutes. – Nick N.

39. The Girl and the Spider (Ramon and Silvan Zürcher)

Following their compelling debut feature The Strange Little Cat, brothers Ramon and Silvan Zürcher double down on their entrancing style with the micro-masterpiece The Girl and the Spider. A dreamy reverie to human connection and feelings left unsaid, the film takes place entirely in an apartment building in the middle of a move-out. Using the parameters of these restrictions, the Zürchers craft one of the great works of art about “nothing happening,” when a closer look reveals the spectrum of human emotion is found in the subtlest of glances and movements. – Jordan R.

38. Funny Pages (Owen Kline)

Owen Kline’s feature debut follows contemptuous teenager Robert (Daniel Zolghadri), an aspiring comic book illustrator who uses the tragic death of his art teacher as an impetus to leave home and begin his life as a starving artist. A love letter to the comic book arts and a thoughtful consideration of talent and privilege, Funny Pages is a welcome exercise in discomfort: a film as textured and awkward as its eclectic cast. – Brianna Z.

37. All That Breathes (Shaunak Sen)

Ostensibly a documentary about kites endangered by harrowing pollution in New Delhi, All That Breathes evolves before your eyes into an account of a family falling apart. Like the birds they protect, brothers Nadeem and Saud are trying to scrape by in a world that is collapsing into chaos. Shaunak Sen’s documentary shows that love, respect, and hard work aren’t enough to survive in a society that values nothing but money. – Daniel E.

36. Mad God (Phil Tippett)

Phil Tippett’s Mad God strips away intention, forgoes puzzles, and decides to do things the hard way––for the art. His lifelong passion project drops us, along with the titular “assassin” character, into a hell world beyond our wildest nightmares. With the studio mandates that everything has to tie into something else, it’s refreshing to witness a stark vision where the narrative map literally disintegrates and we’re left fending for ourselves. We don’t where we’re going; we don’t know where the film is going. All we can do is hang on and witness in wonder and terror. – Soham G.

35. Ahed’s Knee (Nadav Lapid)

Nadav Lapid’s visceral, vitriolic firecracker about a director returning to a small desert town for a screening in his home country is as incendiary as it gets. It’s a film that goes straight for the Israeli people’s jugular, right after it’s done ripping out the Israeli government’s rib cage. You can hear the brilliantly long-winded dialogue coming from Lapid’s mouth as much Avshalom Pollak’s, the explosive lead tortured by what he considers a debased collective morality and total disregard for truth and ontological ethics. But it’s Lapid’s direction that deserves the most praise––an electrifying feast of style, technique, and imagination that draws out the unspokens (of which there are few) of the textured metanarrative and immerses you in every moment with an earned imminence. If it hadn’t been through distribution hell since Cannes 2021, it might have been one of the most talked about of the year. – Luke H.

34. Blonde (Andrew Dominik)

Blonde is ambitious, unwieldy, and jarring, a nightmarish concoction of bizarre photography, suffocating cruelty, and occasional moments of sublime grace. It exists both as a brutal deconstruction of the persona of Marilyn Monroe and a genuinely compassionate portrait of the woman who existed underneath it. It is undeniably divisive and it’s understandable why many have been put off by its depictions of Norma Jean’s suffering. But as it reaches its decaying, heartbreaking climax, Blonde’s inexorable power digs its nails into the flesh of the observer, leaving an unforgettable mixture of despair and transcendence in its wake. – Logan K.

33. Bones and All (Luca Guadagnino)

An arthouse-horror hybrid that romanticizes young love while showing real teeth the way only Guadagnino knows how. In addition to supplying sweaty, blood-stained moments of tension and depicting an innocent, almost defiant pursuit of happiness, this improbably beautiful film transcends its genre DNA to address loneliness, otherness with heartbreaking sensitivity. The entire cast, including a couple of scene-stealing bit players, is ace—Taylor Russell and Mark Rylance, in particular, absolutely slay. Fearless, boundary-pushing work all around. – Zhuo-Ning Su

32. Kimi (Steven Soderbergh)

While clearly influenced by classic paranoia thrillers like The Conversation and Blow Out, Steven Soderbergh and David Koepp’s Kimi forged its own legacy in the subgenre through its reckoning with our increased surveillance state in the digital age. It also benefited from marvelously layered texturing of its main character, a tech worker on the spectrum (Zoë Kravitz) with a meticulousness that never bleeds into hacky tropes. Kimi dropped in February, but these razor-sharp 89 minutes have remained some of the very best all year long. – Mitchell B.

31. Return to Seoul (Davy Chou)

The kinetic energy of Davy Chou’s Return to Seoul rests on the face, and the dancing, of first-time actor Park Ji-min. She vibrates on the screen, her presence reverberating across everyone she meets. She has a tricky task, portraying a displaced soul, a young woman with a lack of place. The emotional chaos splashes on the screen in Chou’s film, heartbreaking in its sudden intimacy. The camera swirls around Freddie (Ji-min) until stillness inevitably comes, a consistent movement as she explores her home country. Ji-min is a revelation as Freddie, soul bared in front of any and all peers that are willing to watch. She’s unpredictable, much like Chou’s film, a switch than can flip at any moment, blistering in her embracing of the pleasures of life. The film hurls itself at the viewer, asking non-judgment and a pinch of trust, knowing that Chou is providing an experience unlike any other this year. – Michael F.

30. The Plains (David Easteal)

The year’s most astonishing exercise in world-building did not take place in some faraway planet but in the confines of a Hyundai Elantra. For over three hours, David Easteal invites us to eavesdrop as two co-workers share a journey home. Well, several. A montage of car rides (eleven total) recorded over the course of a year, the camera placed in the backseat so that all we see of the two is a slanted reflection in the rearview mirror, The Plains is a soul-replenishing road trip that turns us from spectators into passengers. A richly textured portrait of a life, epic in size and probing in scope. – Leonardo G.

29. Triangle of Sadness (Ruben Östlund)

The latest masterwork from two-time Palme d’Or winner Ruben Östlund is a sharp-witted comedy with gross humor and, at times, even grosser politics. Similar to this year’s The Menu, Triangle of Sadness at its core offers a scathing critique of extreme wealth, inequality, and the obsessive masters of luxury items in pursuit of perfection. It’s only natural the film’s initial inquiry asks male model Carl (Harris Dickinson) if he’s a “smiley brand or a grumpy brand.” Rounded out with a superb cast that includes Zlatko Burić as a Russian fertilizer magnate, Woody Harrelson as the ship’s alcoholic yet pragmatic Captain, scheming Filipina custodian Dolly de Leon, and the late Charlbi Dean as Carl’s influencer partner, the film continues to ratchet Östlund’s perverse humor all the way up to an unforgettable, operatic sequence that makes you wish you didn’t see it at a dine-in movie theater. – John F.

28. Fire of Love (Sara Dosa)

It’s more like a drug than a movie. Gorgeous, unbelievably captured visuals of molten, grainy volcanic film footage wash over the viewer while intoxicating them with a delightfully overwhelming sense of hope, love, vigor, ambition, and confidence. As director Sara Dosa proves, Katia and Maurice Krafft are among the most strong, wonderful, generous, intelligent, diligent, and explosively positive forces in human history. Through their footage, we follow the late French volcanologists — like eccentric lovers from a Wes Anderson film — on their lifelong journey to study, film, and educate the public on volcanoes at constant risk of death, a risk they fully embraced together. Reminiscent of 2017’s Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, it’s a vital, invaluable contagion of spirit, a raison d’etre, a world-changing legacy in cinematic perpetuity. Life isn’t worth living without the risk of experiencing it. – Luke H.

27. Everything Everywhere All at Once (Daniels)

The Daniels use humor as our entry point into the quantum physics behind Everything Everywhere All at Once, visualizing their gimmick as a Dadaist adventure through the multiverse that renders explanation moot as propulsion and distraction sweep us aboard before the heart at its core can be unleashed. Their high-concept narrative and miraculously executed special effects ensure the journey towards potential bliss is paved with authentic, universal suffering—any fairytale conclusion the embattled Wang family (Michelle Yeoh, Ke Huy Quan, Stephanie Hsu, and James Hong are brilliant) earns will inevitably come with scars. Because they remind them the fight wasn’t to survive alone. It was to heal together. – Jared M.

26. Il Buco (Michelangelo Frammartino)

With Il Buco, Michelangelo Frammartino returns to the Calabrian countryside 12 years after Le Quattro Volte. Oscillating between a shepherd slowly dying and a nearby cave-diving expedition, Frammartino and cinematographer Renata Berta capture the movement inside their static frames with elegance. A soccer ball is kicked back and forth over the cave entrance, upping the stakes of an errant kick, burning magazine pages float down into the darkness illuminating the cave depths for the explorers and the audience—Il Buco is an experiential ode to death as the final frontier. – Caleb H.

25. Avatar: The Way of Water (James Cameron)

James Cameron’s long-awaited sequel finally arrived. If not to just wax poetic on the photo-realistic Na’vi and the water they inhabit, one has to admire the megalomaniac yet compassionate director’s knack for a satisfying narrative. Culminating in a perfectly constructed final act which shifts from about four different kinds of action sequence, constantly escalating the stakes and managing to conclude with a lovely, Miyazaki-like grace note… well, you can’t help but admire a blockbuster that has the whole package. – Ethan V.

24. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (Jane Schoenbrun)

Jane Schoenbrun did in their debut feature what some filmmakers are unable to achieve over the course of an entire career: establish a new cinematic language. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair synthesizes an eclectic medley of 2010s internet ephemera––vlogs, creepypastas, Skype calls, alternate reality games––into an intimate treatise on gender dysphoria, charting a disturbed teenager’s struggles to excavate her own identity from the sea of digital noise. Part lo-fi horror, part expressionistic character study, World’s Fair accessed parts of my brain I didn’t know movies could. – Cole K.

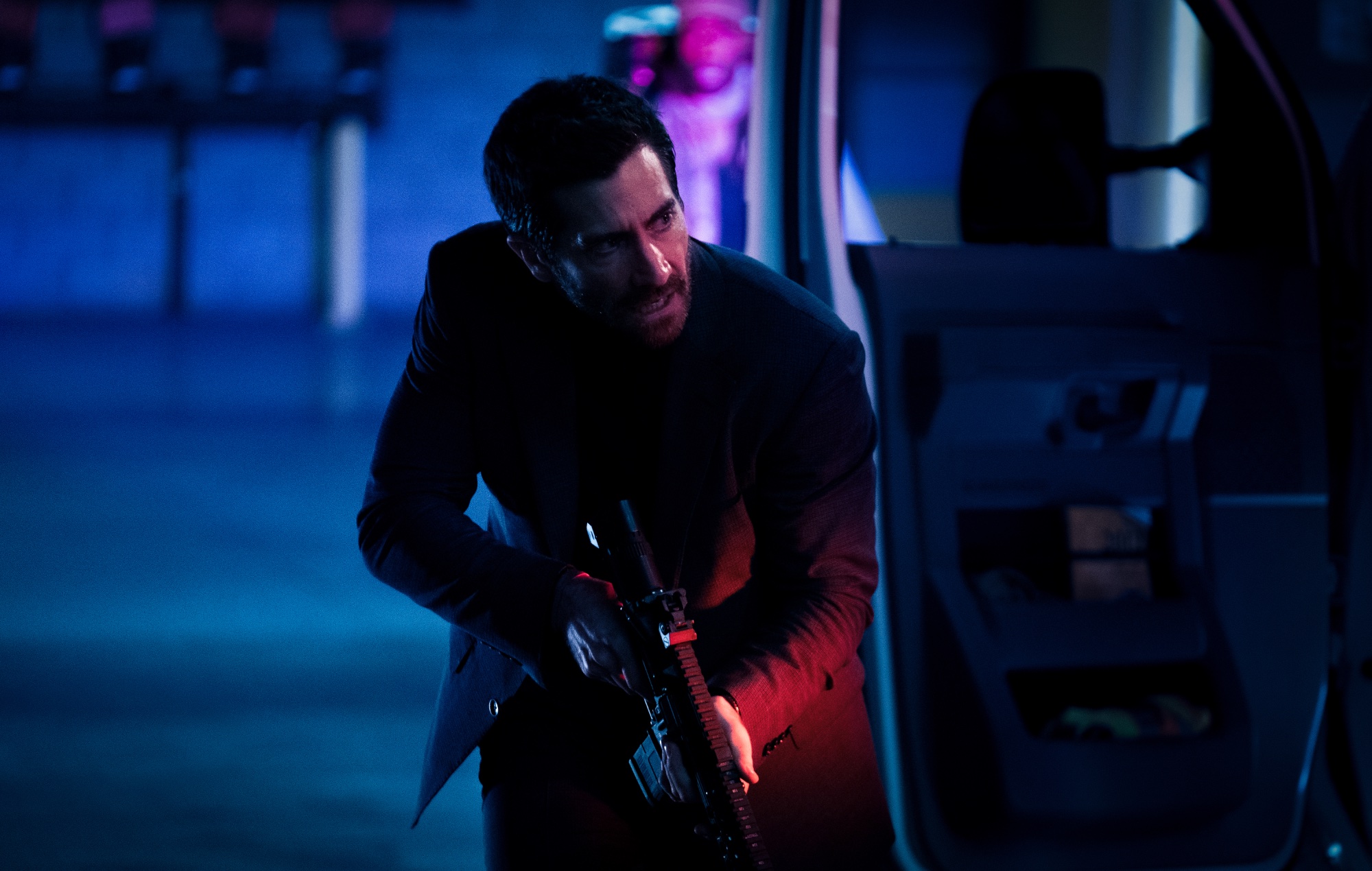

23. Ambulance (Michael Bay)

The best Michael Bay film? Hard to make a case against it. This Jake Gyllenhaal-starrer plays like the culmination of a vulgar auteurist career that started with so much promise (Bad Boys, The Rock), then so much ridicule (Pearl Harbor, etc.), and now so much… begrudging respect? In an age of screens made green and ghosts in the machine, Bay’s work is nearly revolutionary. There are practical effects in his pictures. Actual jokes! Things explode in real life and his actors give performances that often do two things at once. Co-lead Eiza González is better here than she’s ever been. Ambulance was the shock of the year for this writer––an early 2022 cinematic gift that keeps on giving. – Dan M.

22. Jackass Forever (Jeff Tremaine)

In the same vein of cruelty that this bunch of Jackasses inflict on each other, there is a loving, bittersweet feeling to seeing the return of this group of misfits. Still proving to be the best at getting belly laughs from the grossest, most sinister but silliest ways possible, Johnny Knoxville and company pass the torch to a new generation of pranksters. While simultaneously projecting their past and future onto each other with ongoing gags, shaved testicles, and vomit-inducing pranks, Jackass: Forever is one of the best documentaries we have of male camaraderie and the ever-evolving friendship that has lasted through the pain. Though the ghost of the fallen Ryan Dunn looms large, the boys prove that if you’re going to be dumb, you have to be tough. – Erik N.

21. The Novelist’s Film (Hong Sangsoo)

Your mileage may vary on what constitutes the best of Hong Sangsoo’s recent work, but The Novelist’s Film (basically) confirmed my suspicion he’s (more or less) our greatest director. At least it’s 92 minutes as they should be spent: a handful of perfectly measured scenes, an amazingly honest window into the artist’s process, a couple good gags, and while most movies can’t manage one good ending, this boasts two perfect finales. “I love you” has hardly ever sounded so sincere. – Nick N.

20. Elvis (Baz Luhrmann)

What is it about a Baz Luhrmann film? The word that comes to mind is “most.” Whether you like it or not, the Australian auteur is going to put EVERY. SINGLE. THING on the screen. Many love it, many hate it. With Elvis, he’s at his most maximalist. And boy does it work. Austin Butler is pitch-perfect as the titular star, an eternal tragedy constantly thrusting towards something bigger though not necessarily better. Behind him, whispering in his ear, is Tom Hanks as Colonel Tom Parker, offering up a performance that plays like Mephisto by way of South Transylvania. It’s a truly insane turn that’s earned equal parts jeers and cheers. Major studios find themselves in a moment of flux. May they hear this humble suggestion: look to Baz. – Dan M.

19. Pacifiction (Albert Serra)

Every Albert Serra film doubles as an invitation to perceive the world anew, and Pacifiction—in my book, the best film of 2022—is no different. The director’s most narratively driven work to date is a treasure trove of images so entrancing and otherworldly they may as well be telegraphed from a different solar system. Apocalypse Now meets Almayer’s Folly via The Quiet American and Saint Jack, yet the increasingly disquieting visual language is very much Serra’s. For a tale of nuclear annihilation, spies, and international conspiracies, nothing is more heart-shaking and terrifying than the sight of Benoît Magimel riding 20-foot waves off the coast of Tahiti. Now that is cinema. – Leonardo G.

18. RRR (S. S. Rajamouli)

The motorcycle. The dance-off. The tiger. (No, not that one; the other one.) S.S. Rajamouli’s maximalist epic is a three-hour string of adrenaline shots: if you think for even a moment that its well of brio has run dry, it immediately swerves back twice as loud and thrice as imaginative. But for all the ink that has been spilled over this film’s action, it’s the two leads––Ram Charan and N. T. Rama Rao Jr., playing fictionalized versions of real-life revolutionaries Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem, respectively––who give it weight. With their mutual affection and boundless charisma reverberating through RRR‘s every beat, spectacle and sentiment quickly become one, a white-hot bullet rocketing the film toward its explosive climax. Load, aim, shoot. – Cole K.

17. One Fine Morning (Mia Hansen-Løve)

Mia Hansen-Løve’s run of semi-autobiographical work is the nearest thing modern cinema has to a great ongoing novel. And though it’s easy to take for granted films that suggest just a part, not the whole, One Fine Morning marks as complete a vision of a worldview—life’s alternation of pleasure and indignity, triumphs betwixt despondencies—as the filmmaker’s yet managed. Few contemporary oeuvres are such a gift. – Nick N.

16. The Eternal Daughter (Joanna Hogg)

Both of Joanna Hogg’s Souvenir films are haunted by the past, but those ghosts become literal in this stealth third entry in her series of semi-autobiographical works. Despite an artifice of gothic horror, this is the filmmaker’s simplest, most emotionally direct work to date, powerfully re-examining the mother-daughter relationship from those earlier companion pieces via two wonderfully understated Tilda Swinton turns. The revelation as to why Hogg has used a shot-reverse method to keep them out of the same frame might be obvious; it’s no less powerful for it. – Alistair R.

15. After Yang (kogonada)

I had the pleasure to speak with filmmaker kogonada about his stirring treatise on mortality, After Yang, and the moment from that conversation I return to most is him saying that “what makes art so invigorating is that you’re pursuing the ineffable.” This is a notion seeded throughout his gentle, transcendent sophomore feature. We can never truly know another person. In some ways, we will never fully know ourselves or our relationship with the world. But the search for it, the mystery, the endless pursuit—that’s the beauty of life. – Mitchell B.

14. Armageddon Time (James Gray)

Reductively, if somewhat justifiably, pegged as a “white guilt” film, Armageddon Time risked rejection and misreading by nakedly “laying it all out there,” hewing closely to James Gray’s nuanced yet inevitably one-sided perspective on his early life. To paraphrase a recent interview quote of his, spurred by the studio tampering his work has often faced: “if people want to criticism me for the content of my movies, at least I want them to be mine.” This film is his, and while he’s cognizant he and his family look like “jerks”—or much worse you could accuse them of—that honesty, expressed as lyrically as anyone working in modern cinema, is a dear commodity. – David K.

13. Women Talking (Sarah Polley)

Sarah Polley’s adaptation of Miriam Toews’s novel is one of the most powerful, gut-wrenching, genuinely haunting films of recent years. Its story of repeated, years-spanning sexual abuse in a religious colony—and the life-altering decision faced by its women—is deeply upsetting and absolutely unforgettable. Polley has had an amazing career as an actor, writer, and director, and Women Talking is her most resonant and haunting narrative film to date. Between it and her deeply personal essay collection, Run Towards the Danger: Confrontations With a Body of Memory, Polley is operating at a level of artistic innovation that is downright remarkable. And, of course, when considering Women Talking one must mention its stellar lineup of actors, most notably Rooney Mara, Jessie Buckley, Claire Foy, Michelle McLeod, Judith Ivey, and Ben Whishaw. – Chris S.

12. The Banshees of Inisherin (Martin McDonagh)

Set in an Irish coastal town circa 1923, Martin McDonagh’s film exults in the clichés of Gaelic storytelling, reinvigorating trite churches and pubs, gossip and ballads with crisp dialogue and exceptional performances from four leads. An artist, two siblings, and the local halfwit may be trapped in a cruel and isolated village, but their alternatives—terrorist warfare, brute British imperialism, pitiless capitalism—aren’t any better. As dark as McDonagh gets, his insight and empathy are never in doubt. – Daniel E.

11. Saint Omer (Alice Diop)

Great cinema reveals mysteries of the human condition as no court of law could. This infanticide drama examines two women through a prosecutor’s sharp, mistrusting eyes, only to conclude on a note of mercy and motherly understanding. It’s a piercingly insightful investigation of the female experience that exposes justice as an oft-simplified notion. Both lead actresses are sensational. Diop blends the observational focus and authenticity of documentaries with the fanciful touch of fiction to hypnotic effect, marking her as the year’s single most exciting newcomer in narrative filmmaking. – Zhuo-Ning Su

10. Nope (Jordan Peele)

With a flair for the iconic and a knack for remixing familiar tropes, Jordan Peele has been a major filmmaker since his directorial debut. But while Get Out and Us ruled the zeitgeist, their staying power can fade when examined strictly through their central metaphors. Peele’s third film, Nope, isn’t a departure but a bridge between his intuitive filmmaking skills and his puzzle-box structures. A step up in every respect, it affirms Peele as a classical blockbuster craftsman. A director who can wrangle audacious projects with charismatic stars, electric set pieces, and dense mythos without overshadowing his ability to create a great theater spectacle. We need more like him. – Michael S.

9. Decision to Leave (Park Chan-wook)

An insomniac cop becomes obsessed with a possible murderer in Park Chan-wook’s elegant Decision to Leave. Though often known for his violent, sexualized opuses, Park restrains himself here. Only teasing at a possible relationship between Park Hae-il’s cop and Tang Wei’s lovelorn widower, Decision dwells within the quiet moments that stem from their isolation. Technically brilliant and thematically rich, Decision to Leave is not only further proof of Park’s mastery, but also an exciting new direction for the filmmaker. – Christian G.

8. The Fabelmans (Steven Spielberg)

It is, frankly, crazy that Steven Spielberg would completely ape the feel for rising action, tension, and terrible revelation of Minority Report‘s red ball sequence in his autobiography’s dramatic peak, as if he put something of himself into a blockbuster 40 years from that incident and 20 years onward reclaimed the experience he’d given others. Is it even the weirdest thing about this movie? (Christ, I just remembered making-out with the Jesus freak!) The man’s best since Munich only required diving deep into stuff most wouldn’t take outside a psychoanalysis session, resulting in images of unremarkable suburban homes that bear more Spielbergian Wow Factor than his virtual-reality action epic, lavish musical, or Cold War thriller. Never count a genius when they’re in a slight slump. Now good luck to you, and get the fuck out of my office. – Nick N.

7. Benediction (Terence Davies)

Despite its rigorous self-investigation of the desires, truths, and regrets of its main subject, it feels narrow to call Terence Davies’ latest masterwork, Benediction, a biopic. This illuminatingly selective, pointedly distorted recounting of closeted 20th-century poet Siegfried Sassoon isn’t only about his body of work but the act of living with a visible mask and impossible emptiness. Brilliantly played in dual-era roles by Jack Lowden and Peter Capaldi, Davies’ film examines Sassoon as a living symbol against a country that refuses to acknowledge its own moral hollowness. – Michael S.

6. Top Gun: Maverick (Joseph Kosinski)

The legacy sequel’s stock has rapidly plummeted over the last several years—thankfully, Tom Cruise continues to bail out Hollywood’s pervasive lack of creativity, reviving an ‘80s action staple (and character, Pete “Maverick” Mitchell) with the year’s best moviegoing experience. Under Joseph Kosinski’s visceral direction, Cruise returns to the cockpit with a stable of fearless young stars—most notably Miles Teller and Glen Powell—willing to strap into F-18s and commit themselves to unthinkable G-forces. It’s all a testament to Cruise’s unrelenting need to dazzle and inspire a new wave of cinematic daredevils. In his own words, “See you at the movies.” – Jake K-S.

5. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (Laura Poitras)

It is a fascinating thing to watch someone’s history of protest and addiction collide and conspire to hold a pharmaceutical company accountable and expose its parent family as reprehensible. Academy Award-winning filmmaker Laura Poitras profiles the renowned photographer and activist Nan Goldin and her fight through the AIDS and opioid crisis, but this is bigger than a biographical documentary. Through slideshows, interviews, and family videos, Poitras weaves a riveting, heartbreaking interconnected story of generational pain, its influence over the blurry boundaries between life and art. – Jake K-S.

4. EO (Jerzy Skolimowski)

If you’ve ever glanced into your pets’ eyes, something this late-career masterpiece from the great Jerzy Skolimowski does on numerous occasions, you’re likely to love EO. A visually (those drone shots!) and structurally (Isabelle Huppert randomly showing up to smash plates over her fail-son!) audacious work, it excitingly bears the mark of a film that doesn’t set out to be perfect, but actually do something innovative with the medium—even if technically being a “remake.” – Ethan V.

3. Crimes of the Future (David Cronenberg)

Supported by some dozen financial entities and blocks of co-producers but looks very cheap. Largely linear plot that remains vaguely inscrutable, its strands generating dislocated intrigue by running parallel lest they intersect for sake of cohesion. Super-precise lens choices and anemic palette on every off-center close-up. Gross, sensitive; tactile, phony; antiseptic, erection-inducing. What can we say? The old man’s still got it. – Nick N.

2. TÁR (Todd Field)

Although she’d never mention it, we know Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett) endured plenty of toxic male BS on her way to becoming a living legend among composers/conductors. To prove that she could also command the wind. So instead of her struggle to the top, a plot that fiction has shown us before, Todd Field makes us witness her tragic descent. Shot with the clinical precision of a nature documentary and powered by Blanchett’s symphony of a performance, TÁR neither condemns nor celebrates ways in which the powerful achieve and remain in power. Instead it simply observes, capturing a refreshing portrait of female genius, a study of the ravenous affair between art and capitalism, and making us question our belief that the art we love can ever truly be separated from an artist we hate. – Jose S.

1. Aftersun (Charlotte Wells)

What is there left to say about Aftersun? Ever since its unheralded Critics’ Week debut at Cannes, Charlotte Wells’ gut-wrenching debut has been carried on a wave of acclaim so effusive, so gnawingly protective, it’s surprising we’ve yet to see a significant backlash. No other film this year struck a chord with so many. This has been remarkable yet ultimately unsurprising, so acutely attuned is Wells’ beautiful film to the queasy, ecstatic throes of adolescence, the uncertain sands of memory, and terrible finality of a great loss. With pitch-perfect turns from Frankie Corio and Paul Mescal, gorgeous cinematography by Gregory Oke, and the thrilling discovery of a new cinematic voice (dare we say shades of a young Claire Denis?), Aftersun introduced the world to a host of dazzling talents while leaving an emotional mark so indelible that many are still struggling to shake it off. The quietest of triumphs. – Rory O.