After highlighting the most overlooked films of 2021, today we put our spotlight on those that need a home in the first place: movies we loved on the festival circuit—from Berlinale, SXSW, Sundance, TIFF, NYFF, Rotterdam, and beyond—still seeking U.S. distribution.

For acting also as a 2021 retrospective, we hope that highlighting these titles spurs some distributor interests and a release in the next twelve months. Make sure to follow us on Twitter for the latest distribution updates. As we move into 2022, one can also track our upcoming festival coverage here.

We should note that The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet, Taming the Garden, and Liborio nearly made the cut, but they’ll get a digital premiere on MUBI this month.

Ali & Ava (Clio Barnard)

It’s so rare to find a romance between two middle-aged characters in which the main conflict is just baggage of past relationships and past hurt. Ali & Ava is surprisingly sweet, given Clio Barnard’s three previous bleak features. She sticks with her usual Yorkshire setting, but there’s so much love in how she depicts the Bradford community in which Ali and Ava live. Claire Rushbrook and Adeel Akhtar’s chemistry is wonderful. – Orla S.

All These Sons (Bing Liu and Joshua Altman)

All These Sons, documentarian Bing Liu’s follow-up to the 2018’s acclaimed Minding the Gap, finds the Chinese-American director again focusing on empathy. Co-directed by Joshua Altman, the film concentrates on the violence, specifically gun violence, plaguing young men in the South and West sides of Chicago. Like Liu’s previous feature, the doc looks at cycles of destruction, the blurred lines between the mentors and the mentored, and how constant trauma can consume entire communities. Liu remains committed to telling the stories of those overlooked, even if the format isn’t groundbreaking, nor does it need to be. – Michael F. (full review)

As in Heaven (Tea Lindeburg)

Lise (Flora Ofelia Hofmann Lindahl) couldn’t be happier now that she knows her mother’s (Ida Cæcilie Rasmussen’s Anna) determination has successfully overcome her father’s (Thure Lindhardt’s Anders) objections about sending her to school. It’s the late 1800s after all. A big reason why a farming family such as theirs has so many children is to work the land. Sending off the eldest at fourteen isn’t therefore conducive to their home’s machinery—especially since Anders has no qualms with leaving the daily chores to his sister, mother, daughters, and servants while leaving for hours on end. If Lise had anyone else to thank besides her mother for the miracle that is her impending emancipation, it would therefore have to be God. Unfortunately, God’s will has never been purely optimistic. – Jared M. (full review)

The Ballad of a White Cow (Behtash Sanaeeha and Maryam Moghaddam)

The cruelty of the Iranian justice system is in the spotlight again in Ballad of a White Cow, the compelling debut of directing team Behtash Sanaeeha and Maryam Moghaddam that unfurled in competition at Berlin. Just last year, Mohamad Rasoulof won the festival’s top prize for his anti-capital punishment polemic There Is No Evil, a masterful weaving of four storylines that showed how a morally bankrupt state corrodes those forced to carry out its functions, a searing portrait of the banality of evil. – Ed F. (full review)

Come Here (Anocha Suwichakornpong)

In 1953, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais released Statues Also Die, a key work in their fledgling early careers that focused on traditional African art and its exploitation by wider French culture. For the two intrepid modernists, sculptures, masks and other remnants of traditional Sub-Saharan African life had lost their meaning when seen through Western eyes, becoming a mere, hollow commodity. Come Here, a short, potent, and experimental feature by Anocha Suwichakornpong, asks a similar question of the historical memorials that dot our war-ravaged planet. – David K. (full review)

Costa Brava, Lebanon (Mounia Akl)

What can you do when your homeland’s falling apart? The easy answer is stay or leave, but both options carry too much complexity to simply choose and be done. For starters, not everyone has that choice—whether due to finances, family, or myriad other reasons. And those who are able must dig deep within themselves to rationalize why. Do you leave because of greater opportunity? Do you stay because you want to be part of the solution? Or do you find yourself in a sort of purgatory—one foot planted on each side, only to discover your fear of losing out on the benefits of one for the potential of the other has you locked in stasis? That’s where Walid (Saleh Bakri) currently exists. – Jared M. (full review)

Deception (Arnaud Desplechin)

Knowing Philip Roth’s “novel” about an extramarital affair was a barely fictional plaything, Deception starts as story and becomes biography: we witness Roth’s processes, entanglements, nightmares—a literal trial for the crime of misogyny, a copy of My Life as a Man emblazoned with his name being exhibit A—and their ruinous effects on his marriage (no mistake the actress so resembles then-wife Claire Bloom). It’s one of the strangest, most enveloping acts of literary-cinematic matrimony I’ve ever seen, in certain keys akin to Paul Schrader’s Mishima but played through Desplechin’s relentless appetite for set-ups, optical effects, production-design eccentricity, and at its beating heart an unlikely union between Denis Podalydès and Léa Seydoux formed by vivid chemistry. With something like luck the one-two punch of quiet Cannes premiere and misguided reviews won’t render this perpetually unseen. – Nick N.

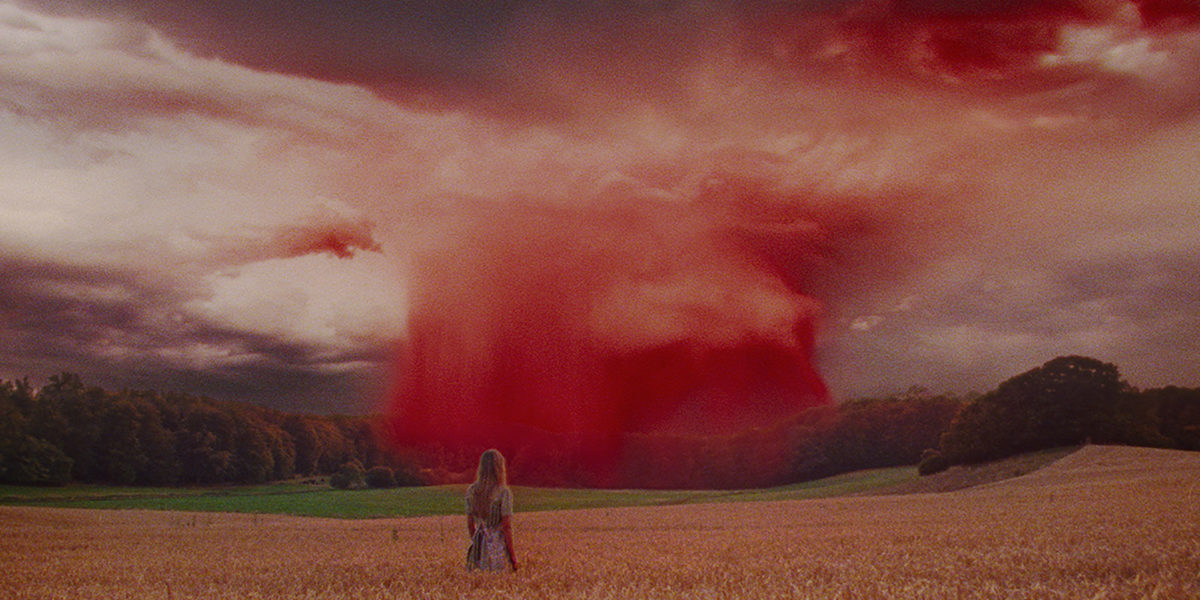

Destello Bravio (Ainhoa Rodríguez)

In the arid, lunar landscape of Ainhoa Rodríguez’s Destello Bravío, a whole village waits for things to fall apart. We’re in the rural outskirts of Spain’s Extremadura region, a few miles from the border with Portugal, but the hamlet remains unnamed—it juts into being from a fable, a land of almost biblical desolation and solitude. The old folks marooned here are the last surviving members of an old species, but the film is so committed to its oneiric and sepulchral fabric that they may as well be dead already. Ghosts in a ghost town. In a tale that draws so much of its perturbing allure from its relationship with the supernatural, it’s fitting that watching Destello Bravío should carry a kind of cosmic quality—like watching a dead star flicker, knowing the source of the light you see died a long, long time ago. – Leonardo G. (full review)

The Fam (Fred Baillif)

The big draw to Fred Baillif’s fictional look inside a residential care facility housing teenage girls is the fact that he refuses to pretend his setting is anything more than a “safe space.” It’s a place to find separation from whatever heinous environment they’ve left and begin the healing process. Some will inevitably be sent back to the place they sought to escape. Some will remain until their eighteenth birthday and suddenly have to figure out what it means to live alone. And no matter how much they all—residents and staff alike—say that they’ve created a new family to replace the ones that failed them, everyone here is too busy trying to survive their own pain to truly be the rock the others need. – Jared M. (full review)

Farewell, My Hometown (Wang Erzhuo)

Chinese cinema is at a weird place. On the one hand, three of 2021’s top five worldwide grossers are, as of writing, Chinese, so it’s doing more than okay on the money front. But not one Chinese film made the competition lineups of Berlin, Cannes, or Venice, which could be a first in decades. The pandemic might have something to do with it, but ever-tightening censorship is more likely the main reason. One has the sense that, for a country / industry teeming with resources and talents, less and less room is allowed for artistic expression. As such, it is lovely to see a film like Farewell, My Hometown, director Wang Erzhuo’s narrative feature debut which premiered at the Busan International Film Festival, and be reminded of the potential of the Middle Kingdom’s cultural output beyond war epics and populist comedies. – Zhuo-Ning Su (full review)

Feast (Tim Leyendekker)

In the mid-2000s several men committed a heinous crime in the Netherlands: they would bring men to their home for sex parties, drug them, and then inject them with their own HIV-infected blood before dumping them on the street. Filmmaker Tim Leyendekker tackles this notorious story in his first feature Feast with a unique approach, splitting his film into seven parts that deal with the crime in different ways—real documentary interviews, faux documentary interviews, dramatic recreations among them. The specificity and horror of what happened would be enough for a director to create something more conventional from this true-crime story, but Leyendekker refuses to make a single minute of his film go down easy. Each vignette reframes the incident in a new light, challenges assumptions, and at some points comes close to sympathizing with the perpetrators’ romantic view of what they did. One of 2021’s most provocative films, Feast bucks the current inclination to make up viewers’ minds—perhaps why it’s unlikely to release in North America. – C.J. P.

FIRST TIME [The Time for All but Sunset – VIOLET] (Nicolaas Schmidt)

Romance is front and center in Nicolaas Schmidt’s FIRST TIME, even if it’s not obvious. The opening plays Robin Beck’s power ballad over footage of ’80s Coca Cola ads of people showing outward expressions of love and affection before it transitions to the main event: a 40-minute single take of two young men sitting across from each other on the subway, total strangers who sit in silence on their commute while throwing quick, stealthy glances at each other every now and then. Schmidt sets the scene but leaves plenty room for interpretation, given the setup of the shot itself. You can admire views of Hamburg during golden hour; you can hone in on the soundtrack of post-rock tunes combined with the hustle and bustle of passengers; you can see a tale of unspoken queer romance building before your eyes; or you can just get bored senseless by two guys sitting on a train. FIRST TIME is a film made up of possibilities, and by laying them all out so plainly it makes a strong case for acting upon one’s own desire rather than letting the moment pass. – C.J. P.

House Arrest (Alexei German Jr.)

Alexei German Jr.’s latest takes place entirely in and around the apartment of David (Merab Ninidze), a middle-aged professor who finds himself charged with embezzlement not long after making a social-media post mocking his town’s mayor. He refuses to accept the charges and confess, standing his ground against false claims from authorities to keep him quiet. Once set up, House Arrest unfolds as a series of interactions between David and others (neighbors, a policeman, his lawyer, his ex-wife, thugs sent to intimidate him) as the screws tighten and the world closes in—he loses his job, friends, and loved ones while waiting for trial. German Jr. takes a straightforward direction in his script (co-written with Maria Ogneva), which could easily be seen as commentary on present-day Russia but can be applied almost anywhere (German Jr. refuses to call House Arrest a political film). Through its limited setting, gradual plot developments, and strong performance by Ninidze, House Arrest shows how those in power can abstract and trivialize one’s principles to make people bend to their will. The conclusion provides a clear resolution to David’s case, but remains ambiguous about whether or not David’s protests were worth the effort. – C.J. P.

Ludi (Edson Jean)

Arriving on the festival circuit just as a group of Ivy League-educated millionaires in Congress punted on raising the minimum wage, Edson Jean’s Ludi is an often riveting work of social realism following its title character, a health care aide played by Shein Mompremier as the chases her American Dream. A Haitian immigrant living in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, she engages in spirited debates throughout her daily life, asking her bus driver why he left a dictator in Haiti while embracing Trump’s MAGA politics. For Ludi, anything is possible in the US even if she often feels as if she’s working to survive. In one passage we learn her job at a nursing home has taken away her vacation days because she didn’t use them. – John F. (full review)

Madalena (Madiano Marcheti)

Madalena is never just a name in Madalena, Madiano Marcheti’s haunting debut film about the murder of a trans woman set in rural Brazil. For some she’s a source of income and friendship, and for others panic and loss. The film follows a trio of characters whose disparate lives all somehow overlapped with the lifeless person now lying in a vast field of green soy crops. In doing so, Marcheti’s film presents varying reactions to trauma that ripple outward, revealing the subtle nuances of societal intolerance and personal grief. – Glenn H. (full review)

Miguel’s War (Eliane Raheb)

Eliane Raheb’s latest sprawling documentary is Miguel’s War, a character study of a gay Lebanese man named Miguel who now lives in Spain but is still dealing with the trauma of the Lebanese Civil War and grappling with his part in it. Raheb, who appears onscreen, is an uncompromising documentarian. Her affection for Miguel is so evident in this witty, passionate film, which incorporates animation to express Miguel’s vibrant inner world. But she cuts no corners interrogating Miguel about his difficult past. – Orla S.

Mr. Bachmann and His Class (Maria Speth)

I have no doubt that, when released, Mr. Bachmann and His Class will make many want to become teachers. This three-and-a-half-hour German documentary about a retiring educator genuinely flies by: we follow Bachmann over a year teaching his final class of young kids. It’ll remind you of how life-changing a good teacher can be—the power they have to teach a young mind empathy, respect, and the ability to listen. – Orla S.

Natural Light (Dénes Nagy)

For his first narrative feature Natural Light, Hungarian filmmaker Dénes Nagy (who has worked in documentary since as far back as 2008) follows in the footsteps of a fellow countryman. In 2015, László Nemes debuted Son of Saul at the Cannes film festival. A deeply serious film, Saul sought to plunge viewers into the horrors of Auschwitz. Nagy’s film takes place a little earlier, and a good bit further to the East, following a squadron of Hungarian soldiers on the Eastern front. The men are there to serve on the side of the Nazis-––although hunger, mud, and sanity seem to be the more pressing concerns. – Rory O. (full review)

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (Arthur Harari)

Arthur Harari’s Onoda (subtitled 10,000 Nights in the Jungle) tells the true story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier stationed on the island of Lubang in the Philippines circa 1944. When news came of Japan’s surrender he refused to believe it and spent the next three decades in seclusion, refusing to leave his post (he finally left in 1974, when his former commanding officer was flown in to relieve him of duties). It’s an extraordinary tale that poses the challenge of conveying its central character’s superhuman levels of devotion and denial, which Harari takes on by going long. With a runtime of more than 160 minutes, Harari takes time to establish and develop the story, opting for a total immersion in the jungle environment and a dedication to realism that makes it hard not to eventually give yourself over to the film with a full level of commitment. Onoda’s ability to sweep viewers up into its detail and realism makes its final act come as a sort of shock, as the inevitable ending to this long chapter of Onoda’s life reveals a strong emotional undercurrent that comes seemingly out of nowhere in its moving finale. – C.J. P.

Pebbles (Vinothraj P.S.)

The striking Pebbles is set in Arittapatti, a village in southern India terrorized by draught so persistent it has turned fields of green into yellowish dust and forced grandparents and grandchildren alike to spend their days trying to catch the mice that escape from their burning holes in the ground. Father Ganapathy should be out there with them but prefers to day-drink and chain-smoke instead. Perhaps he has been like this ever since his wife left him. Or maybe he’s always been that way, and that’s why she left him. – Tim B. (full review)

Petite Solange (Axelle Ropert)

A mood of heightened melodrama gives way to something strangely enchanting in Petite Solange, the story of a 13-year-old girl coming to terms with the shattering notion that her parents’ love (and for that matter anyone’s) might not last. The director is Axelle Ropert, a French critic, actor, writer, and filmmaker whose career has pivoted between the genre films she and her partner, Serge Bozon, have collaborated on (La France, Madame Hyde) and her own body of work behind the camera. That personal side to her oeuvre has always tended more toward the familial and the bittersweet (The Wolberg Family, The Apple of My Eye), just as it has proven Ropert a keen proponent of the Tolstoyan idea that happy families are only intriguing when torn apart. – Rory O. (full review)

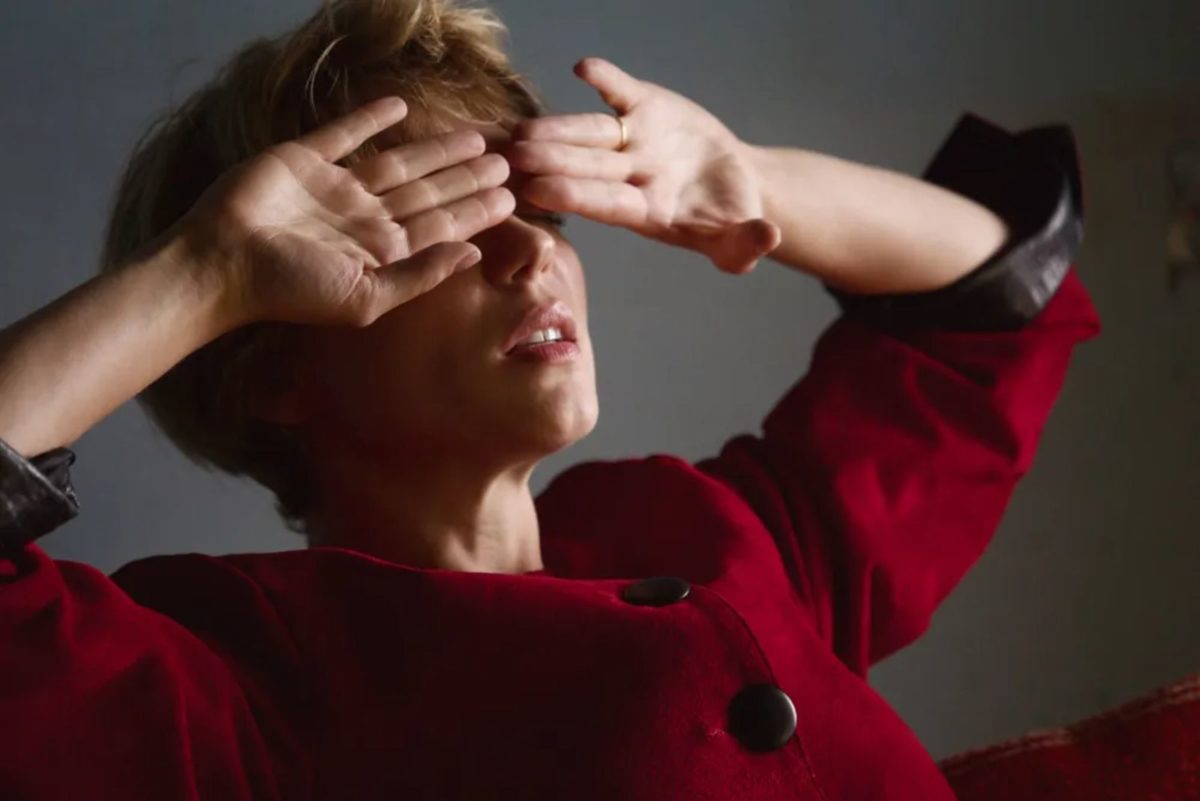

Petrov’s Flu (Kirill Serebrennikov)

Petrov’s Flu opens on a stuffy commute—a Moscow bus in the early years of post-Soviet Russia. The eponymous protagonist is already bent over a handrail, stricken with his affliction. The mood is fevered, almost circus-like, the lighting like pea soup. In a moment of madness, Petrov (played by Semyon Serzin) is dragged from the bus by militiamen in Mexican wrestling masks. Hard rock plays. He takes a gun and joins their firing squad, mowing down some nameless humans. The mind briefly wanders to Brazil, and somehow Songs from the Second Floor. – Rory O. (full review)

Public Toilet Africa (Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah)

Impeccably dressed, eyes shielded by sunglasses and arms dangling from the windows of their Nissan pickup, Ama (Briggitte Appiah) and Sadiq (David Klu) breeze through Ghana like twenty-first century cousins of Anta and Mory, the Bonnie and Clyde couple in Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki. They’re the two young people at the heart of Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah’s Public Toilet Africa, a picaresque, irreverent journey where a model seeks revenge for her childhood traumas. Or at least that’s one of the many films tucked inside writer-director Ofosu-Yeboah’s feature debut. Public Toilet Africa is several things—a revenge tale, a road trip, a tale of a city and a remote village; a courtroom drama—and if the ride isn’t always smooth, the end result is a rebellious and oneiric portrait of a country wrestling with the specters of colonialism. – Leonardo G. (full review)

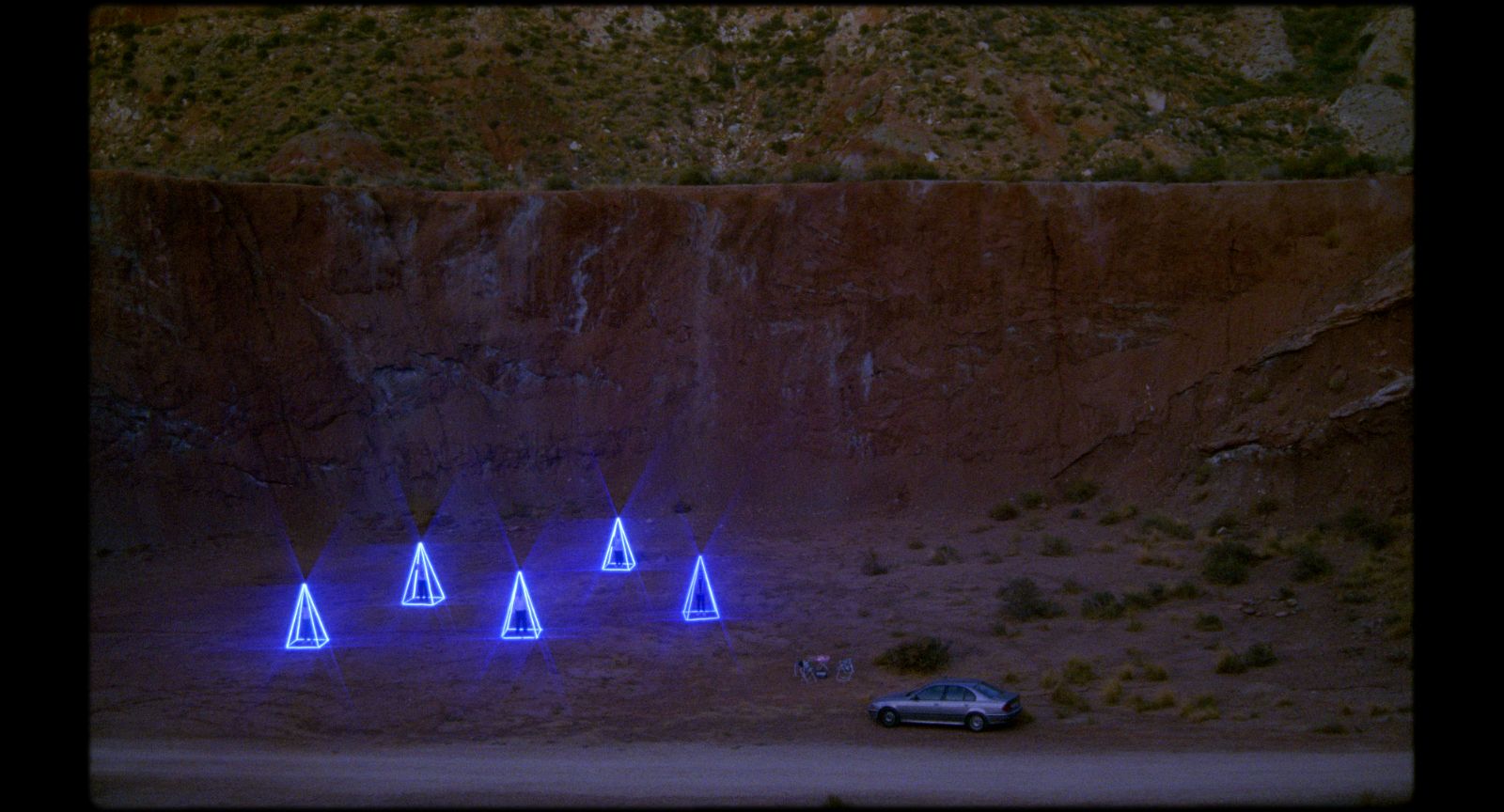

The Sacred Spirit (Chema García Ibarra)

Welcome to the OVNI-Levante Ufology Association, please take a seat. It’s the 37th meeting for this band of alien-obsessed misfits from Elche, Spain, and the last to be chaired by president Julio before he’ll pass away and leave the helm to his second in command, “Cosmic Pharaoh” José Manuel (Nacho Fernández). Not exactly the best time for a cabinet reshuffling, considering the six-strong OVNI-Levante has spent the past few months (years?) gearing up for a cosmic event which, the President has promised, will change the world as we know it. The date is looming; there’s no time to lose. Is it an extraterrestrial sighting these drifters are bracing for? An invasion? And how, if at all, is the mystery related with the disappearance of José Manuel’s 10-year-old niece Vanessa, gone missing 25 days ago? – Leonardo G. (full review)

Saloum (Jean Luc Herbulot)

The infamous “Hyenas”—three mercenaries running amok throughout Africa—are caught in the air with gold bars, the drug lord (Renaud Farah’s Felix) they’ve been hired to extract, and a failed fuel tank leaving them with bad and worse options for an emergency landing. The Guinea-Bissau authorities won’t let them leave without a fight on the ground and they’ve surely alerted their Senegalese counterparts already, but Chaka (Yann Gael) knows of a secret beach from his past where they might be able to lay low and find the materials to repair their plane’s damage. Rafa (Roger Sallah), the muscle to Chaka’s brains, doesn’t like the idea while Minuit’s (Mentor Ba) mysticism has him believing their leader is hiding come crucial details, but they follow him just the same. – Jared M. (full review)

Searchers (Pacho Velez)

Searchers was one of the most delightful films I saw at Sundance. It’s a simple, sweet, romantic documentary that presents a series of vignettes of New Yorkers attempting to navigate online dating. Director Pacho Velez presents these talking heads in single, unbroken takes, with dating apps superimposed on the screen. What’s most impressive is the editing, which structures these segments so they go from making you laugh out-loud to unexpectedly earning tears. – Orla S.

Scarborough (Shasha Nakhai and Rich Williamson)

Taking place in the shadows of the Greater Toronto area and a liminal space of poverty, Scarborough isn’t an easy film to shake. A local, low-budget indie premiering in TIFF’s Discovery section, written by Catherine Hernandez (based on her novel) and directed by Shasha Nakhai and Rich Williamson, the film traces three turbulent childhoods of three families grappling with a system that has set them up to fail and fall through the cracks. Opening with late-night escapes from abusive situations and into housing insecurity, it bursts with a raw immediacy. Shot and edited by co-director Rich Williamson, he brings a Frederick Wiseman-esque sensibility to certain moments within formal institutions—doctors’ offices and a daycare that become a sanctuary beyond their intention. – John F. (full review)

Social Hygiene (Denis Côté)

An aura of pure eccentricity billows off the new film by Québécois provocateur Denis Côté, like a fug of stale-smelling nitrous oxide. Akin to his prior work only in its magpie-like experimental sensibility, Social Hygiene finds the festival mainstay delving into the static visuals of filmed-theatre presentations, but with a postmodern streak that collapses historical eras and cinematic conventions at will. All through its compact but still satisfying 75-minute runtime, the viewer is liable to ask, “What on earth is this?”, and by its finale, this unanswered query feels rewarding as opposed to exasperating. But you can still feel Côté chuckling behind our backs. – David K. (full review)

Taste (Lê Bảo)

Lê Bảo’s Taste is set in Saigon, but for the best part of its 97 minutes, all action is confined to a bunker-like abode where five people meet and hide. The place is dark, unfurnished, and dank; so spectral in its emptiness you’d wonder if the quiet tenants are alive or ghosts. In the stunning chiaroscuro of their unlikely home all motion slows into choreography, characters freeze in a state of protracted wait, and there seems to be only a very blurred distinction between the dreaming and the dead. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Teenage Emotions (Frederic Da)

Watching Frederic Da’s Teenage Emotions can feel like a bit of a shock at first. Shot entirely on iPhones in extreme close-ups, Da films teenagers around a Los Angeles high school in what looks like raw, point-and-shoot footage. In its opening minutes, the shoddy and garish nature of the visuals makes the film look like it could be mistaken for an assignment made by one of its characters. But in no time these perceived flaws turn out to be the film’s greatest assets. On a surface level, Teenage Emotions is an ugly film, but that ugliness helps give it a vitality that makes it one of the most authentic and entertaining portraits of high school in ages. – C.J. P. (full review)

A Thousand Fires (Saeed Taji Farouky)

The first time we hear music in Saeed Taji Farouky’s mesmeric A Thousand Fires is also the first time we’re offered a glimpse of the viscous substance around which the whole documentary orbits. Set in the Magway region of Myanmar, it concerns a family struggling to make ends meet by drilling oil in an unregulated field—a Heart of Darkness-like landscape dotted with derricks, huts, and countless fires. We open with a man cranking a manual well, but it takes a few moments for Farouky to show the fruits of his work; when it happens, the oil splashes through the frame in a kaleidoscope of colors, an impossibly gorgeous vision of shapeshifting hues, accompanied by a synths-heavy melody, a murmur of the Earth. It’s a marriage of sounds and visuals that turns oil into a magic potion, an amniotic liquid, less a resource to be exploited than an ancestral lattice tying humans and land together. – Leonardo G. (full review)

You Resemble Me (Dina Amer)

The worlds of contemporary geopolitics and narrative independent filmmaking collide in You Resemble Me, a movie that shape-shifts from a first act coming-of-age tale into something searing and provocative, and ripped straight from the headlines. Bold and scattered, it marks a formidable debut for Dina Amer, a first time director who emerges with no shortage of credentials: an award-winning journalist of Egyptian and American extraction (her work has featured in CNN and the New York Times) and associate producer of the Oscar nominated The Square, Amer is perhaps best known for her role as a political correspondent for Vice (also producer here), a job that that took her to the front lines of human-trafficking in Syria, among other precarious situations. (As it becomes apparent, her’s is a film that demands such lofty qualifications.) – Rory O. (full review)

Yuni (Kamila Andini)

Kamila Andini further proves herself of Indonesian cinema’s most vital voices with her third solo feature Yuni. Partly inspired by Sapardi Djoko Damono’s love poem “Rain in June,” the movie paints a candid portrait of what it’s like for a teenage girl in Indonesia, where expectations and dated traditional values often prevent one from fully having the freedom to pursue their dreams. – Reyzando N. (full review)

Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash (Edwin)

Back in the ‘80s, martial arts B-movies from Hong Kong made their way into Indonesian cinema. People were obsessed with them because they were fun and entertaining, and most of all reflected the hyper-machismo culture that bloomed in the country during the regime of Soeharto from the late ‘60s to the end of the ‘90s. Most Indonesian men, influenced by how the country was ruled, were all about virility. If they didn’t know how to fight, they weren’t manly enough. However, in Edwin’s brilliant and offbeat sixth feature, the Golden Leopard-winning Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash, this toxic trait of the country gets knocked down in a story about erectile dysfunction. – Reyzando N. (full review)

We Burn Like This (Alana Waksman)

Making its rounds on the regional festival circuit, Alana Waksman’s We Burn Like This is an impressive debut feature about cultural, historic, and personal trauma set in Billings, Montana. Rae (Madeleine Coghlan), a wayward young woman, seems to live a typical country life at first glance, hanging with best friend Chrissy (Devery Jacobs) at the local pubs to perhaps suppress an impending emotional storm. The descendent of Holocaust survivors, Rae navigates what becomes a personal persecution set against the backdrop of a deeply divided, angry country in all respects, from anti-Semitic flyers to a boy she picks up at a local watering hole. Coghlan is the commanding presence in a film full of mysteries and myths, becoming a road movie as Rae sets out on a path to understand the past and her place in the world. We Burn Like This is a powerfully moving drama of self-discovery, full of haunting emotional ambiguity with a strong sense of place, and one deserving of a wider audience in 2022. – John F.