After giving rundowns on various categories when it comes to 2012 in film, it is time to strictly take a look at the best. With well over a thousand films watched across all contributors on The Film Stage, eight of us have picked our personal ten favorites, along with a few honorable mentions. With most films already available to view in theaters or at home, the following should give one a mountain of viewing material well into the New Year. Check out our editor-in-chief’s look back below and continue on for more rundowns from fellow TFS’ers.

Jordan Raup’s Best Films of 2012

After starting off surprisingly strong with Haywire and The Grey, 2012 was yet another good year to be a film fan. Although it may not have included some instant favorites like last year’s The Tree of Life or A Separation, it’s difficult to complain about the selection. The year also saw a handful of talent defy expectations, including Channing Tatum showing off his funny side in the hilarious 21 Jump Street and Matthew McConaughey in a variety of roles, with both teaming up for the summer’s best wide release, Magic Mike. However, none of the aforementioned made the final cut, but one can see what did by checking out my rundown below.

Honorable Mentions

Top 10

10. Girl Walk // All Day (Jacob Krupnick)

It’s always a struggle to find a film for this spot, so I decided to go with a feature that brought a smile to my face from beginning to end. Running just 75 minutes, on the surface this dance film following one woman’s journey through the streets of New York City, motivated by the sounds of Girl Talk‘s All Day, is simply just fun. But look deeper and we have a fascinating experiment, giving us a glimpse at how much better the world would be if we expressed as much joy as break-out star Anne Marsen.

9. Sound of My Voice (Zal Batmanglij)

Discovering new talent is always a delight and the up-and-coming duo that surprised me most this year was director Zal Batmanglij and actress Brit Marling with their small-scale story of a cult infiltration, Sound of My Voice. With a enigmatic structure that keeps one on the edge of their seat, but never lost in the puzzle, this is a knock-out debut that has exceedingly intrigued me for what’s next.

8. Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino)

It’s no surprise that Quentin Tarantino gave us one of the most entertaining films of the year with Django Unchained. Handled under anyone else, we have a concept that would simply not work, but this auteur proves yet again his ability to effectively mash genres, delivering a rollicking good time as we journey through the South for one of his strongest emotional throughlines, following the story of Django and the search for his wife, Broomhilda. It’s simply too early to tell now, but if it’s anything like the vast majority of Tarantino films, it will only get better with age.

7. Samsara (Ron Fricke)

I usually look to the documentary form to deliver some of the most fascinating stories of the year, but rarely do I expect something as jaw-droppingly gorgeous as this. Ron Fricke’s long-in-the-making journey across the world will open your perspective on not only unforeseen locations, but the human experience itself, confronting us with both the unsettling facts and raw natural splendor, all in stunning 70mm.

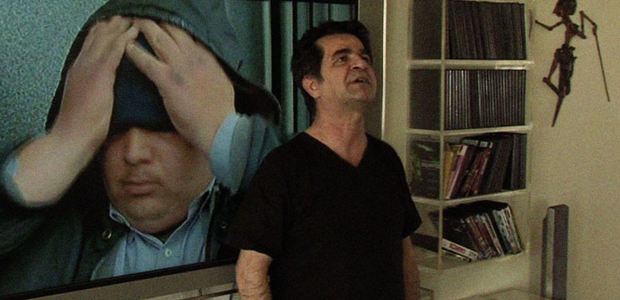

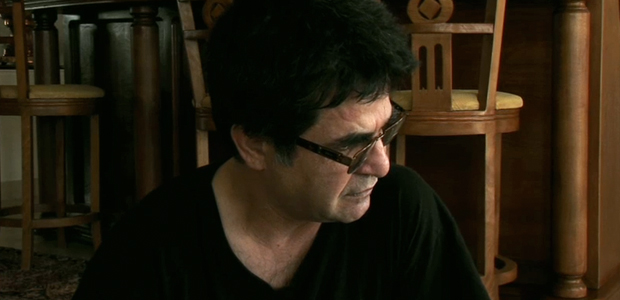

6. This Is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi)

While most of our knowledge regarding an artist’s struggle comes from behind-the-scenes accounts, this personal documentary from Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi brilliantly captures such an internal battle. Forced to stay within the confines of his own home, we witness a transformative look at means of film itself and how the smallest of productions can deliver the most powerful of messages.

5. Goodbye First Love (Mia Hansen-Løve)

The best coming-of-age film of the year is sadly one of the most overlooked. What begins as a fairly standard, but intimately captured, story of young passion quickly blossoms to one of the most mature takes on such an event thanks to Mia Hansen-Løve‘s remarkably natural style (it’s no surprise to learn she’s wife to Olivier Assayas) and a script that’s conscious of time and its effects on love. Praise must also go to Lola Creton and Sebastian Urzendowsky for seemingly organic chemistry from such material.

4. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

While most crime films are all about the hunt for the culprit, few take a look at such a specific time in the process as Once Upon a Time In Anatolia, and even fewer will have you as captivated with every shot. Although this deliberately paced drama may seem to carry out in real-time, this notion comes as a compliment as one will feel the entire breadth of this rich journey. As we sit inside intimate reflections amongst the law and criminals in a small cop car, or hang out on the side of the road as an investigation proceeds offscreen, the images and themes director Nuri Bilge Ceylan conjure up leave an indelible impression.

3. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow)

Special mention this year goes to Megan Ellison‘s Annapurna Pictures, with one of her films already mentioned above and one more to go, but this sprawling, intense story of one woman’s hunt to capture the most wanted man on the planet is one of the most expertedly crafted and acted films of the year. Taking a considerable leap after The Hurt Locker, Kathryn Bigelow‘s drama is the ideal snapshot of this vital time in history and one that will be required viewing for years to come.

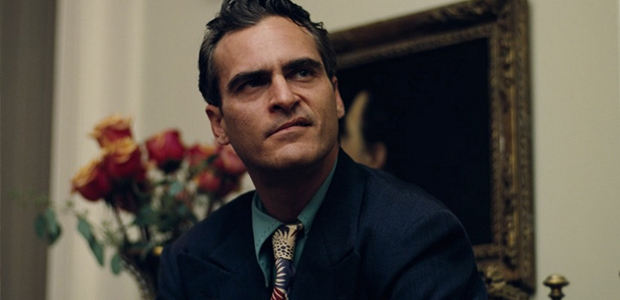

2. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

An enigma of an experience, Paul Thomas Anderson‘s sixth film is his most rigid, while still commanding our attention at every turn. Featuring the best batch of performances of 2012 thanks to Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Amy Adams, this story of a drifting soul and what happens when he sparks a connection is one of the most rich, detailed relationships the year has to offer.

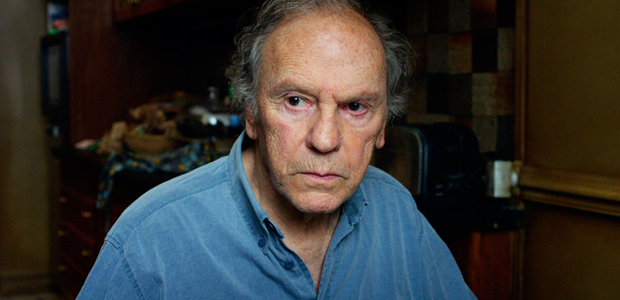

1. Amour (Michael Haneke)

While the phrase “til death do us part” is often featured in many films, and something I proclaimed earlier this year, rarely is it seen carried out. In the hands of Michael Haneke, I would have never expected him to deliver the most emotionally resonant film of the year, but his timid tale of a couple holding on as one is forced to let go of life is the sole masterpiece of 2012. Filled to the brim with specific moments I’ve reflected on for hours, but also working as an overall, life-changing experience, one will never look at death — both their personal struggle and caring for those nearing the end — the same way.

Dan Mecca’s Best Films of 2012

Though the year may not have been the creative juggernaut it could/should have been (with new films from P.T. Anderson, Spike Lee, David Cronenberg, Andrew Stanton and Ridley Scott, my hopes were very high), there were some undeniably bright spots.

And though the best of them are listed below, I’d be remiss not to mention the smart, violent Looper, the daring Anna Karenina and the beautiful The Impossible (perhaps the best shot movie of the year) as strong contenders sadly left off. And let us not forget the top-notch performances that came out of Silver Linings Playbook and Flight.

Now then, to the list:

Honorable Mentions

Top Ten

10. Burning Man (Jonathan Teplitzy)

A quiet, soulful and devastating look at a man who’s lost the love of his life, Jonathan Teplitzy’s film features an incredibly honest performance from Matthew Goode, one of the most underrated performers working today. Goode matches Teplitzy’s flashy camera moves punch for punch, making what could have been a rudimentary melodrama into some that’s so much more.

9. Tchoupitoulas (Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross)

This is the way documentaries should be made. In following three brothers as they journey to a place they’ve never been before, filmmakers Bill and Turner Ross watch young men discover themselves and face some very real fears. All in one night.

8. This is Not A Film (Jafar Panahi)

Jafar Panahi’s personal statement on his state of creativity as it relates to his physical state of house arrest (within his home country of Iran) is cinema at it’s purest and most important. With perhaps as much honesty as a man can offer on the subject of himself, Panahi struggles with the burgeoning narratives in his head as his own narrative becomes something bigger each second the camera continues to roll.

7. Compliance (Craig Zobel)

This affecting, horrifying thriller gets under your skin slowly, decision by decision, exploring the moral evils of persuasion without the weight of responsibility. We watch the characters involved and the choices made and can’t believe something like this could happen. Then we remember it has, and will again. And what makes these people so much different than us?

6. Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie (Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim)

The duo that specializes in absurdist comedy builds their magnum opus here, a feature-length something-or-another that is worried about one thing and one thing only: being as irreverent as possible about any and all subjects. It works 95 percent of the time, and it’s the funniest 95 percent of the year.

5. Seven Psychopaths (Martin McDonagh)

Coming off the much-loved In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths offers many more laughs and just as much violence. The difference, however, is McDonagh’s willingness to eschew the central narrative he builds for something lighter and more peaceful. We watch his characters struggle with the change, the writer fighting with the writer.

4. Oslo, August 31st (Joachim Trier)

This journey into the world of one who is damned is unforgettable. Anders Danielsen Lie offers up one of the best performances of the year, working perfectly against director Joachim Trier’s calm, confident direction. All involved know the importance of simple, concise storytelling, and the result is astonishing.

3. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

Over a decade passed between Holy Motors and French auteur Leos Carax’s last feature, and the director was clearly determined to make up for lost time. In one film we get several strange, bewildering, provocative tales lived by our hero Oscar, played with chameleonic brilliance by Denis Lavant. And yet, the chaos all feels controlled. This may be the ultimate comment on cinema.

2. Les Miserables (Tom Hooper)

Unabashedly grand and on-the-nose, Tom Hooper’s bold imagining of the classic musical features some of the most intricate, inventive production design of the year along with the great Hugh Jackman in the role he was born to play. The timeless themes have never been more affecting, the characters never more heartbreaking.

1. The Deep Blue Sea (Terence Davies)

Romance at it’s most simple and most tragic. Davies has been making elegant, brutal films his whole life, and this might be the best of them all. Rachel Weisz so perfectly captures the feel of unrequited love it hurts to watch. You’re afraid she might break at any moment. The great Tom Hiddleston, the object of her affection, plays the other side perfectly; he watches what he’s doing to this woman, but doesn’t know how to stop the pain.

Nick Newman’s Best Films of 2012

2012: the year many a soft-skulled individual thought cinema made its way toward the exit sign. I don’t know what the fuck these people were even going on about. (Allow yourself to consent to frankness.) It’s not just that our finest living artists are still producing top-tier work — something I can either attest to or, for the time being, have to take the reliable word of others on — but also knowing there are new world talents coming into their own as the decade moves forward. The medium and its “culture” — whatever such a broad, loosely-used term can even signify, thank you very much — are still going strong.

The less humble part of yours truly likes to think this list can exemplify as much. Deciding on numbers 10-6 forced me to edge out films which, up until oh-so-recently, would have landed here without regret, while entries 5-2 could almost be a four-way tie. Although the crown jewel is, really, in a class of its own (hence it being a “crown jewel”), this is like any proper year-end rundown: not so much about ranking films as about commending them.

And there are still multiple entries I hope to encounter in the coming weeks and months. Here are those I, being a schmuck, didn’t have a chance (or the proper time) to see which, otherwise, may have landed here: Alps, Amour, I Wish, Neighboring Sounds, Tabu, This Must Be the Place and The Turin Horse.

Honorable Mentions

Top Ten

10. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Having only seen this once — and with that, too, being a recent viewing — it feels a little unfair that I’d give this film a “last-place” spot on my current top ten. What Nuri Bilge Ceylan is doing here doesn’t completely facilitate some sort of instant reaction — past that of the simple good / bad sort, of course — but one of long-term consideration and parsing. Nevertheless, an initial glance (that’s only about a week fresh) has given incentive to hail Once Upon a Time in Anatolia as a delicate, intimidatingly deliberate rumination on ethics, country, occupation, and social class which, better yet, is built upon a great premise. If you’re looking for the kind of film its plot outline would suggest, you may want to reconsider your options. Jettison those expectations and you’ll be handed a far-flung wonder.

9. The Loneliest Planet (Julia Loktev)

This, like the film discussed right above, is a slow burn of the highest caliber. Trying to pin down what makes such a bizarre film so effective in one tiny capsule is no easy task, except to say (if nothing else) that the temporal rhythm of Julia Loktev’s film is one of the most precise I’ve seen in recent years; that she, Gael García Bernal, and Hani Furstenberg could manipulate it as a point-counterpoint to observant, bruising human drama is the greatest compliment I could pay The Loneliest Planet. Don’t be content to just bother with my praise, though — not that anyone is going to do that, let’s be honest here — but take the plunge and fall under its spell for yourself.

8. Skyfall (Sam Mendes)

This film, on the other hand, does not have the same sort of flavor. Being a longtime fan of James Bond, through thick and Brosnan, there is an admittable (though not at all regrettable) smidge of bias when it comes to the pleasures afforded by Skyfall. Yet so plentiful they are, and so well-laid is the entire film, that it’s sort of for naught. Daniel Craig continues his emotionally fractured journey as what is, now, the world’s most-reluctant secret agent with the best team to ever converge over 23 franchise entries, bringing together a motion picture that’s as enjoyable to watch in the moment as it is to consider in the lens of a greater legacy. Throwing that into the equation, this might be the best instance of 007’s own.

7. The Comedy (Rick Alverson)

In thinking about The Comedy, there’s one central thing which refuses to escape my brain: that Rick Alverson, with whom I had zero prior association, is able to deliver both the funniest and most upsetting sequences I encountered this entire year. It’s because of an unbreakable commitment to performance — speaking both literally and figuratively — which defines the film from first scene to last, and which also makes it hypnotically compelling even as you’re repulsed out of your own skin. This is not everyone’s speed — I doubt it could ever truly be “the speed” of anyone with a good conscience, actually — but those who can go with it ought to come out shaken from and grateful for the experience.

6. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s sixth feature is not nearly as inscrutable as many were wont to proclaim some four months ago; seen from a distance, this is a work ultimately dependent on what someone brings to it themselves. For the purposes of this list, many of the emotional conduits which allowed myself to tap into this story of a wayward veteran — so long as it’s acceptable to be so reductive and call The Master the story of a wayward veteran — are too personal to get into here… so focus on what’s more rigidly applied, shall we? (I swear, none involve an aunt.) While there’s (truly) nothing new to be said about Joaquin Phoenix’s lead performance, the exhaustion to which it’s been covered only speaks to the strength and magnetism supplied in nearly every scene, even as it threatens to consume everything else in The Master along with it. But the “everything else” is of such exemplary caliber — framing, lighting, image & sound editing, that damn Jonny Greenwood score — that Anderson, in the end, pulls off his finest balancing act yet. If things can feel a little, well, wayward at various points, we can blame the drunken sailor at its center.

5. Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino)

The best filmmaker to emerge these past 25 years — a number applied out of kindness for those who might’ve jumped in a bit earlier — rides into his third decade in no short supply of something to proclaim. While Django Unchained is absurdly entertaining in its own right — so much so that it could earn a spot on this list for that much alone — it’s no less invigorating to see Quentin Tarantino take further steps in his role as, if you’ll allow another plaudit, far and away the most crucial voice American cinema currently has at its disposal. What we have here is a deep, dark journey into the helmer’s country, but that doesn’t discount the immeasurable work of his partners in crime — at first glance, the most notable being a triptych of onscreen players who, though invaluable on their own, coalesce as something altogether more special. That Django Unchained can be a genuinely warm, humanist work amidst the explosions of blood and hurls of expletives says more than I could ever hope to.

4. This Is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi)

Technically the only documentary on my list (a gross oversight for which I have no truly reasonable excuse), but throwing one label on it is none-too-wise. I think This Is Not a Film would deserve a place if it was only the most important work of cinema I’d seen all year, though even something about that, as well, feels like a simplification. Taken on its own terms, the picture is a remarkable blur between fact, fiction, and the sort of creative impulse that drives presentations of either; knowing the real-world consequences that may ensue for Jafar Panahi — as well as his co-director, Mojtaba Mirtahmasb — in simply making it happen, Film is embedded with a real-world power that could render nearly everything else on this list moot.

3. Cosmopolis (David Cronenberg)

A young and wealthy man goes to get a haircut, and on the limo ride through Manhattan loses the last remnants of his soul. But does he actually gain something greater along the way?

This is only one of many, many questions which lie at the heart of Cosmopolis, a film that’s been plaguing yours truly as if it were some consuming disease David Cronenberg would’ve made the central focus as a younger man. Now being older and, I think, wiser for it, the horrors have become more real, tangible, and relevant — not that I want to make this out to be a total downer. Seeing Robert Pattinson cavort around town in a limousine, diners, bookstores, and, eventually, even a barber shop — all as he (sometimes intimately) interacts with an incredible ensemble — is, honest-to-God, a hugely thrilling time. And what else can you say about the soundtrack by Howard Shore & Metric? Not much when you only want to bask in a paramount work of modern ennui.

2. Lincoln (Steven Spielberg)

Despite being a minor student of history in my private time, biopics of the big figures have rarely struck a chord. If anything separates Lincoln and elevates it to a work that can feel as monumental as the man himself, it’s the vantage point taken by Steven Spielberg and scribe Tony Kushner. Much more a wounded reflection of feeling than rigid document of fact, here we have a picture about the way men can pivot the strengths of (immense) power and complexities of democratic process to steer the course of history for some greater good. But by no means is this saccharine in its execution; there’s something oddly cynical about the story. At Lincoln’s heart, after all, is a man who could hardly keep his own life in order, nor carry out some great act of humanity without paying for it in the blood of others and, finally, the blood of himself. The idea itself isn’t wholly new, but it’s a delivery that’s so resolute and so moving that I can’t believe a major fall release is able to stick that landing. There isn’t even enough time to dig into the strength of its performances or, in addition, the great formal resilience of its creators — but, at the end of the day, I think this is an accomplishment to be moved by. The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

1. Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson)

I’m sort of amazed to find this standing at the top.

Although there were, prior to 2012, a pair of great films (and some very good ones) to be found in Wes Anderson’s oeuvre, his work has rarely spoken (or sung) to myself. But after a second viewing of Moonrise Kingdom — following a quite positive (albeit somewhat reserved) initial encounter — when I was fully aware of its quirks and turns, did I also find myself surrendering to it like the throes of young love. In telling a cute, seemingly simple story about two 12-year-old kids who, in 1965 New England, run off to get married, the co-writer (alongside Roman Coppola) and director has made something as socially observant as it is internally complex. Let’s not stop short: Moonrise Kingdom may, if you’ll pardon the candor, replicate the feeling of being in love — that at one moment wonderful, at the next moment horrifying sensation which weighs down your entire body — more than any film I’ve ever seen. Personally, the experience of watching Anderson and co. work magic in a tiny, 35mm theater one warm night in June is so perfect that I’m almost afraid to venture with Sam and Suzy once more. Yet, finally, I think Moonrise Kingdom is one for the history books.

Raffi Asdourian’s Best Films of 2012

2012. The year that the world was supposed to end, would have also resulted in the end of cinema (something Godard predicted years ago). Yet no fiery comets, zombie apocalypse or nuclear explosions occurred to disturb the daily routines in our lives. However had it really been the rapture, the world of cinema would have ended on an unusually high note. Despite not seeing a handful of films (Zero Dark Thirty, Cloud Atlas) that could have ended up on my list, there was no shortage of fantastic movie experiences to have this year, making it yet again a memorable time at the cinema.

Honorable Mentions

Top 10

10. Room 237 (Rodney Ascher)

In Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237, the filmmaker assembles a group of obsessed Stanley Kubrick loyalists to carefully examine, frame by frame, some of the hidden messages behind his controversial 1980 film The Shining. Dissecting the various conspiracy theories that have popped up over the years, the deconstruction of Kubrick’s cult hit is akin to obsessing over the Zapruder film of Kennedy’s assassination. More interesting however, is what Room 237 says about film criticism in general while illuminating the idiosyncratic obsessions of one of the greatest American auteurs in the history of moving pictures.

9. Killing Them Softly (Andrew Dominik)

Few crime dramas elicit a sense of foreboding and tension like Andrew Dominik’s neo-noir Killing Them Softly. Based on the novel Cogan’s Trade, the film centers around an inside job gone wrong set amidst the backdrop of the 2008 presidential election. Featuring an all star ensemble cast including Brad Pitt, James Gandolfini, Ben Mendelsohn and Ray Liotta, Killing Them Softly is a fascinating case study of how the corruption of the capitalist American Dream can make people utterly ruthless.

8. Compliance (Craig Zobel)

Rarely do films fill you with a sense of rage to the point of wanting to throw something at the screen because it is impossible to believe what is unfolding before your eyes. Such is the case with Compliance, Craig Zobel’s intense interpretation of a series of real-life events involving a serial hoaxster who prank calls fast food restaurant employees. Deeply unnerving and disturbing, Compliance is a film that will stick with you long after the final frame, despite making you angry and frustrated by the obedience of its unsuspecting victims.

7. Looper (Rian Johnson)

Sci-fi films are hard to take seriously and even harder to make compelling. Yet in the time traveling mind bender Looper, writer/director Rian Johnson makes a case for why he’s one of the most interesting American filmmakers working today. Weaving together narrative threads like a masterful puppet master, Looper is the closet thing to a modern day Blade Runner we might ever get. It also features the best performance to date from rising star Joseph Gordon-Levitt while simultaneously establishing a new amazing genre of film, action sci-fi film noir.

6. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson is arguably the most revered contemporary American filmmaker and rightfully so, with an impressive body of work that pushes the envelope for the art of cinema. With The Master, PTA has crafted his most enigmatic film to date but also perhaps his most provocative. Featuring electrifying dueling performances from Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix, dizzying and wondrous cinematography and an ominous soundtrack from Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, The Master is an exercise in masterful filmmaking.

5. Like Someone In Love (Abbas Kiarostami)

Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love is a daydream set amidst the neon lights of Tokyo.The follow-up to his excellent Certified Copy, it’s the second feature shot outside of his home country of Iran. But shooting in a foreign country doesn’t mean the director is straying from themes that have dominated his body of work since the early 70s and his ability to reflect the natural unexpectedness of reality. Like Someone in Love is a subtle work of genius that will challenge audiences not patient enough to absorb the details, which is clearly the filmmakers intention.

4. The Raid: Redemption (Gareth Evans)

If you are a fan of action movies, you will love The Raid: Redemption. Welsh-born director Gareth Evans’ Indonesian martial arts thriller is a delicate tapestry of gun battles, machete blades and flying fists. In a space surrounded by superfluous excess and mundane hyperbole of Hollywood, the film distinguishes itself for its raw unflinching power. The Raid: Redemption is by no means a masterpiece of high art cinema, nor does it want to be. It’s perfectly content being the most bad-ass action movie of the year.

3. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr)

Prior to seeing The Turin Horse, I was completely unaware of Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr. After seeing it, I devoured his entire body of work and now consider him one of my favorite filmmakers. Shooting always in stark black-and-white and with a style reminiscent to Andrei Tarkovsky, Tarr demonstrates a masterful understanding of composition while forcing you to question his narrative intentions. Deceptively simple in its repetitive nature, The Turin Horse is an illuminating work of philosophical cinema that is both deeply intriguing and affecting.

2. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

In the delightfully surreal Holy Motors, filmmaker Leos Carax seems to be channeling the absurd sensibilities of Luis Buñuel melded with Jean-Luc Goddard. Despite the seemingly endless randomness of each scene, there is a definite undercurrent about how the artifice of filmmaking is morphing into the new digital age. Featuring a series of outlandish vignettes strung together by the chameleon-like performance of lead actor Denis Lavant, Holy Motors is a breathtaking spectacle of cinema to witness and a testament to Carax’s ability to create unforgettable imagery.

1. Amour (Michael Haneke)

There is a certain indescribable manner in which Michael Haneke is able to lure you into his films that leaves you in a state of both shock and awe. Such is the case with Amour, a heart-wrenching and unflinching portrait of an elderly couple confronted with the inevitable demise we all face. In showcasing the intimate pain of watching someone you love slowly suffer, Haneke takes a departure from his usually emotionally detached narrative tropes, offering his most humane film to date. Featuring the two best performances of the year from Jean-Louis Trintingant and Emmanuelle Riva, Amour is an incredible testament to the power of love while forcing us to question our own morality when confronted with the clocks of fate.

Danny King’s Best Films of 2012

2012 was a magnificent year for the movies, a sentiment that has been expressed in a number of year-end lists already. And it was equally magnificent, for me, on a personal moviegoing level — I saw (and reviewed) more new releases this year than I have in any previous 12-month period, and I think the heightened productivity ultimately encouraged more nourished relationships with many of these films. This is certainly the most time and effort I’ve ever put into crafting a Top 10 list — I’ve seen many of these films more than once, for instance, because I wanted fresh, recent indications of the kinds of feelings a given film stirred inside of me. As a result, I am very confident in and proud of the following lineup — though, as always, I would hardly be surprised if, two or three years down the line, I looked back on it and said, “What was I thinking there?”

Honorable Mentions

Top 10

10. Beasts of the Southern Wild (Benh Zeitlin)

I like to think of nearly every frame of this film as being filtered through the child’s-eye point-of-view of the six-year-old Hushpuppy, played with such resilient force by newcomer Quvenzhané Wallis. The dazzling dexterity of cinematographer Ben Richardson is something to behold, his camera always sticking close to the ground, trying to catch Hushpuppy’s bobbing, weaving eye-level. And I think the film’s at its most memorable when director Benh Zeitlin, in his feature debut, plunges himself as intensely as possible within Hushpuppy’s consciousness. The image of Dwight Henry‘s raging Wink lifting Hushpuppy at the moment of her birth, or the sight of Jovan Hathaway’s mother figure exiting her kitchen in a shaft of blinding light, grasping Hushpuppy’s attention like the fireworks that give the film its title card — these are the impressions I’ll remember most, because they show us what it’s like to be a kid in a way that movies rarely do. The heartbreaking father-daughter dynamic, of course, is the other calling card — the core of the film, really — whose emotional remnants make way for that towering final shot that somehow achieves the scope of Terrence Malick.

9. Tabu (Miguel Gomes)

Miguel Gomes’ black-and-white jewel is movie magic at its most ripe and thrilling, doing for me what The Artist did for so many others last year. Split into two distinctly stylized halves, it’s the second one, by design, that still lingers like a bedside photograph. A tender love story marked by refreshingly dialogue-free attraction, the second half of Tabu is also a laborious, intensely accurate depiction of how the process of memory actually works. These sections of the film even brought to mind Malick’s The Tree of Life in the way they substitute choreographed conversation for on-the-spot spontaneity and deliberate, pensive voice-over. And that’s to say nothing of how much of an extravagant mish-mash of elements Tabu is on the whole, shoving together things as disparate and fantastical as symbolic crocodiles and eccentric witchcraft.

8. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow)

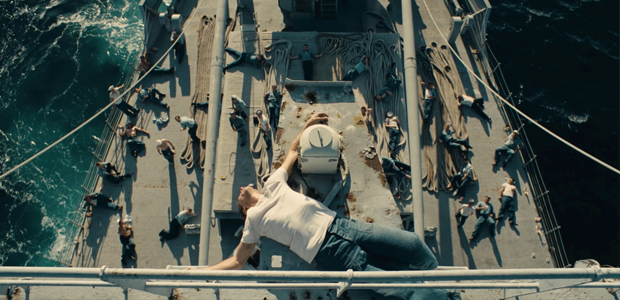

Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal‘s impressive, tenacious follow-up to the Best Picture-winning The Hurt Locker is a hard-as-nails procedural, grilling us with office-place details at breakneck speed, rarely breaking its cover to reveal moments of character and emotion. The result is an important, essential film, at once epic and intimate in scope, painting the decade-long manhunt for Osama bin Laden against a steely, resolute performance from Jessica Chastain, who creates a very precise and memorable character in the job-obsessed Maya. I love the overall ensemble, too: Mark Strong‘s entrance-making monologue is a gruff, raspy triumph; Jennifer Ehle‘s Jessica is admirably driven, and especially likeable as she gets to know Maya better and better with each passing scene; and Jason Clarke, in what may be the film’s best performance, is brutally unforgettable as a chain-smoking torture specialist who somehow molds seamlessly into the home-base world of taking phone calls and selling yellow Lamborghinis for high-priced information. Props to cinematographer Greig Fraser, too, whose work is exciting throughout, and never more so than in the lime-green night-vision used in the climactic raid on Abbottabad.

7. Elena (Andrey Zvyagintsev)

Directed with master-class precision by Andrey Zvyagintsev, this is a chillingly contemporary noir treasure, sketching modern-day Moscow as a city in which the people always have their fangs at the ready, sharp and prepared to chomp. During my first visit with the film, that’s the thing I came away with most — the remorselessness of these people, and the accuracy with which Zvyagintsev captures it through frosty production design and cold-hearted camerawork. But a second viewing — perhaps unsurprisingly, since the film crackles with assurance from its very first frame — revealed greater depths, not only in its cynicism, but also in its profoundly ambiguous commentary on the cost-benefit consequences that familial responsibility can yield. It makes you think about why the titular character — so generously and complexly performed by Nadezhda Markina — is compelled to do such dirty things for such a dirty batch of folks. Oh, and one more thing: Someone needs to give Elena Lyadova her own movie right this instant.

6. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr)

Béla Tarr‘s career-capping film is a monster of formal exertion and thematic punishment. It’s a film that affirms and then reaffirms Tarr’s singular cinematic signature, because it tackles subjects so broad and far-reaching — life, death, mortality, physical labor — that only a filmmaker of a certain caliber could pull them off without outstepping his or her bounds. And Tarr does exactly that, staring these themes directly in the eye like a hunter ready to eliminate his prey. Composer Mihály Vig, turning in a melody of barbaric roughness, and cinematographer Fred Kelemen, whose black-and-white photography is viciously rough-hewn, provide the film with its momentum-keeping lifeblood, giving monotonous, repetitive events an arresting pressure and gravity. (If the film were a comedy, its redundancy would recall Samuel Beckett.) What stings most, then, is how penetratingly Tarr communicates something elemental about the nature of human physicality. It’s a shame that this film left theaters so quickly, because the big-screen environment is really quite necessary to feel the full force on display.

5. Amour (Michael Haneke)

Michael Haneke‘s cinema has long been defined by an interest in meta-textual discourse — think of the self-conscious structuring of Code Unknown, the anonymous cameraperson that haunts Caché, even the horror-genre discussion of Funny Games. These are films that are as much about the director’s process itself as they are about characters and stories. The Palme d’Or-winning Amour, however, does away with all of that stuff, and what results isn’t an easily accessible film by any mainstream standards, but still one that presents Haneke as a man who’s finally let his guard down. Using his customary choices of technique — a rigid, static camera, coupled with takes that are held far past their expected expiration date — Haneke drops the viewer into the Parisian apartment of Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). Not long into the film, Anne gets sick, and for the next two hours, we watch as Georges cares for her, trying to keep her alive and well as long as he can. Amour is a devastating film that does justice to two topics that the movies screw-up all too often — love and old-age. Even as I sit here writing about the film, attempting to convince you to seek it out, I know that this is one of those vintage executions that words can hardly describe.

4. Lincoln (Steven Spielberg)

Here is a great American film that deals in gentle strokes — fireplace conversations, political debates fought about over candlelight, documents signed next to the illumination of a lantern. Shafts of sunshine also come in through the windows, brightening the banter-clogged rooms of the White House with an angelic force. Janusz Kaminski, Steven Spielberg‘s regular cinematographer, sets a remarkable visual tone through these contraptions, and it’s one of many artistic decisions made here that contributes immensely to the film’s profound central conceit: to both humanize and dehumanize Abraham Lincoln at the exact same time. As written by Tony Kushner, directed by Spielberg, and acted by the superhuman Daniel Day-Lewis, this interpretation of the American icon is definitive in every sense of the term, making Lincoln a relatable, earthly figure while simultaneously enhancing his timeless power, the presence he still carries in the lights of our homes. All of this resonance, and I’ve yet to even mention the film’s detailed, enduring portrait of the American political process.

3. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

This is one of those stone-cold achievements in which the structural scars tend to be as revealing and rewarding as the sequences of consummate construction. Not everything in Paul Thomas Anderson‘s searing There Will Be Blood follow-up works for me — the film’s second half is especially problematic — but it’s so boldly accomplished on every level, from Mihai Malaimare Jr.‘s bravura lensing to Jonny Greenwood‘s herky-jerky score to the exquisitely furnished post-WWII production design. And it’s really a savagely emotional film, when you get right down to it — many people have claimed that the film’s most cryptic creations keep them at a distance, but even when I’m not sure if I’m picking up what The Master is putting down, I’m still sucked into the experience, like a moth to a flame.

Joaquin Phoenix‘s full-bodied freak-show of a performance is about as naked as you can get, dismissing common understandings of (method) acting and bulldozing his way into an ostrich-like physical embodiment that defies conventional description. The first time I saw the film, I thought Philip Seymour Hoffman‘s customary theatricality was an intentional foil to Phoenix’s unhinged technique, but the more I observe the film — and the more times I hear Hoffman deliver what is surely one of the most memorable curse-words ever spoken in a film — the more I think that Hoffman is every bit as deranged as Phoenix, completely lost in a character that he himself may not even fully understand. And that’s exactly why these two guys are in love.

2. The Grey (Joe Carnahan)

As much about fending off hungry wolves as Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is about finding a buried body, Joe Carnahan‘s survival story is a miraculously raw and severe construction, slowly stripping away the layers of its male-dominated cast until they have nothing left to do but sit around the fire and talk about the meaning of life. It’s a startlingly existential piece of work, especially when considering how numbingly one-note the trailers made it appear. But to elevate Carnahan’s film solely by comparing it to the so-so expectations — something I’ve seen done countless times — would be to cloud the fact that The Grey, purely on its own terms, is absolutely a first-rate accomplishment, exploring mortality (a theme also dissected in Amour and The Turin Horse, among others named here) with a gutsy, gravel-voiced strength. Liam Neeson gives one of the year’s most under-appreciated performances, as a man who detests his life and tries to kill himself within the film’s first five minutes. And look at the breathing room Carnahan gives to lenser Masanobu Takayanagi, who takes hold of the Alaskan wilderness like a bruised warrior, an approach further amplified by the film’s sound work, which creates an entire character out of the shrieking wind. There’s a beautiful little poem somewhere in there, too.

1. Oslo, August 31st (Joachim Trier)

I thought I appreciated Oslo, August 31st when I saw it back in May — I turned out to be dead wrong. At the time, I found it to be a fine piece of work, a tight, compact character study, but a touch inferior to Reprise, Joachim Trier‘s exciting debut about two young men whose close friendship is tested by literary competition. But as the year went on, something about Oslo kept calling me back, and when I eventually gave in and re-watched the film, it was a transformative experience. I don’t think I understood as much about any other character this year than I did about this film’s drug-addicted protagonist, who is played by Anders Danielsen Lie in a performance of such aching vulnerability that you almost have to turn away from it at times for a gulp of oxygen.

There are moments here — the opening prologue, which hauntingly fills us with the soundscape of a city’s memory; the café scene later on, where Anders can’t help but look around and stuff his head with thoughts about the far more promising lives of the people around him; the agonizing resignation on Anders’s face as he watches his fleeting friends enjoy an early-morning swim — that take my breath away in the depth and economy with which they dictate character and place. (I’m occasionally reminded, structurally, of Alain Resnais‘ masterpiece Hiroshima, mon amour, another film that juxtaposed a very short-lived character study against the backdrop of a city’s history.) Oslo, too, is one of the few addiction-related films I can remember where I can actually explain through tangible evidence why a character has no other choice than to stick a needle into his veins. Though that may sound overly depressing, the refinement of the film — the reason I will continue to come back to it again and again — is that there is something endlessly euphoric about getting to know a human being as well as Trier and Lie allow us to get to know Anders.

Jared Mobarak’s Best Films of 2012

Devoid of many true standouts—only two films garnered four stars from me when the past decade’s average has been around five—2012 has evolved into a pretty solid year nonetheless. And with works such as The Loneliest Planet, Zero Dark Thirty, and Tabu yet to be seen, it may still improve. As of now, however, it has been the myriad examples of devastating dramatic gravitas that has left its impression. Performance has surpassed artifice in a way where calling it simple enhancement would be a disservice. Between fresh breakouts (Beasts), familiar faces hitting their prime (Silver Linings), and some senior gems reminding us how it’s done (Amour), last year’s spotlight on the auteur has moved on to the actor.

Honorable Mentions

Top 10

10. Rust & Bone (Jacques Audiard)

A deeply affecting film inundated with tragedy upon tragedy in the hopes its broken souls will learn their lessons and accept responsibility for their unfortunate lives, Jacques Audiard‘s Rust and Bone is as good or better than his universally-lauded A Prophet. To me it is in fact more accessible through its beautiful depictions of human struggle by Matthias Schoenaerts and Marion Cotillard, selfishly using each other until discovering the cautious love they covet.

9. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

An out-there, sensationalized science fiction fantasy about an actor living between reality and fiction as a hired star inside the lives of each person on Earth, Leos Carax mixes genres in a series of short vignettes connected by our desire for escapism. We love to wear masks and become people we are not if unable to live vicariously through strangers, oftentimes forgetting who exactly it is we are. An exercise in the grotesque, the sensual, the musical, and the beautiful, Holy Motors must be seen to be believed.

8. Sound of My Voice (Zal Batmanglij)

Tautly wound dramatics shown through a filter of sci-fi appear to be writer/actress Brit Marling‘s calling card. Sound of My Voice will have you guessing about its truth from the opening frame, steadily progressing in a sequence of chapters moving towards answers about cult lifestyle, faith, and the power of love. Nothing is quite as it seems whether you believe the words of the prophet Maggie or not.

7. Inch’Allah (Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette)

A powerful look at a war-torn Middle East full of Israeli and Palestinian hostilities, Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette‘s Inch’Allah shows us how naïve idealism can be flipped on its head once a people’s suffering can no longer able to be held at arm’s length. Evelyne Brochu‘s performance as Chloé will shatter you once her juggling of two worlds collapses in on itself and bigoted hatred forces her to make a decision that will reverberate through her soul for perpetuity.

6. Beasts of the Southern Wild (Benh Zeitlin)

Benh Zeitlin‘s Beasts of the Southern Wild has been one of the year’s most talked about films with good reason. A unique vision made more intriguing by the fact it is American, this dark fantasy set in the Louisiana bayou amidst an environmental apocalypse for its citizens uninterested in the outside world will literally transport you there through its stunning visuals, water-logged and mud-streaked sets, and gorgeous score. The discovery of young Quvenzhané Wallis is but one of its highlights, the metaphorical parable seen through her imaginative mind grabbing hold until the final frame.

5. ParaNorman (Chris Butler and Sam Fell)

The fact Hotel Transylvania and Rise of the Guardians—two surprisingly adequate animated films—beat out Laika House’s ParaNorman for a Golden Globe nomination is nothing less than highway robbery. A poignant tale dealing with issues of bullying, being yourself, and familial bonds, there is something to love for children and adults alike. The borderline frightening finale and visually ostentatious conclusion only show the level of creativity and intelligence possessed by a studio fearlessly refusing to pander to its audience.

4. Cloud Atlas (Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer)

Possibly the most ambitious film to hit theatres this year, Wachowski Starship and Tom Tykwer did what many believed impossible with David Mitchell‘s sprawling novel Cloud Atlas. A genre-bending mash-up of stories set against a spiritual backdrop throughout time and dealing in good vs evil/slave vs oppressor, the end result is an emotional hurricane of sumptuous visuals and assured performances from actors tackling up to six different roles. Too blockbuster to be an indie darling and way too cerebral for box office success, it’s still nothing short of spectacular.

3. The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Stephen Chbosky)

Coming out of nowhere and knocking me to the floor with its authentic humor and pathos, Stephen Chbosky‘s adaptation of his own book excels at getting everything right. The Perks of Being a Wallflower may not contain standout moments to be talked about for years to come as unique cinematic achievements, but there isn’t one false note either. Logan Lerman shows us his talent, Emma Watson sheds Hermione Granger, and Ezra Miller entertains in a role far removed from his breakout in We Need to Talk About Kevin. This is adolescent tumult in a nutshell and you’ll be projecting your own past onto it before the end.

2. Looper (Rian Johnson)

The less you know about it the better, Rian Johnson may have outdone his brilliant debut Brick with his science fiction masterpiece Looper. Quite possibly airtight despite its genre’s penchant for easy plotholes, the time travel premise is merely an atmospheric element providing the impetus for its look at the human soul inside a world not so different than ours. In fact, the gangster-fueled looping through the decades isn’t even its most important or exciting tropes. Johnson retains more than a few hidden tricks up his sleeve, only unleashing them when the perfect moment presents itself.

1. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

It may not be plot-heavy or contain an overflowing ensemble cast, but Paul Thomas Anderson‘s The Master is still very much his. Looking to share an intimate portrait of his conflicted leads, this not-so-thinly-veiled interpretation of Scientology is a hotbed of mesmerizing performances. In a perfect world Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman would each receive an Oscar as the poetic story structure floating through an unspecified period of time provides them a playground to be as dangerous, insecure, and powerful as necessary. Definitely not for everyone, you cannot deny it’s gut-punch impact or refusal to let you back on your feet.

Jack Giroux’s Best Films of 2012

If the whole Mayan apocalypse hoopla ended up correct, 2012 wouldn’t have been a bad way to end movie history. There were more than a few great films this year, some of which didn’t even make this top 10 or the honorable mentions. What did crack my favorites of the year were some of today’s finest filmmakers, and new ones, firing on all cylinders. They gave us the best of them, as we expect from pros like Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino and William Friedkin. Let’s all hope 2013 reaches that high bar.

Honorable Mentions

Top 10

10. Silver Linings Playbook (David O. Russell)

Even David O. Russell can make “middle-of-the-road” feel fresh and new. Silver Linings Playbook hits every single beat we expect from a romantic comedy, yet coming from this director, he handles those formulaic moments with grace. A few punches may have been pulled by O. Russell, but, even so, he hits where it matters the most for this kind of film: the heart.

9. Lawless (John Hillcoat)

The only movie of John Hillcoat‘s any sane viewer can label as “fun.” Lawless is about as conventional as a period coming-of-age tale gets, but also as enthralling. Hillcoat makes every gunshot and brawl leave an impression, never forgetting the effect violence can have on people. While the ending of Lawless may toss that philosophy out the window for an all too padded ending, the Nick Cave-penned film is the type of crowd pleaser I hope we see more from Hillcoat in the future.

8. Killer Joe (William Friedkin)

A lovely little nasty piece of work. Tracy Letts‘ Killer Joe, like many of William Friedkin‘s most famous works, isn’t afraid to rub an audience’s face in the uglier side of human nature. Killer Joe does just that, in a sophisticated, grimy B-movie way. Friedkin creates a fully realized world involving characters who seek more in life, and how that misguided desperation will lead to very, very bad things.

7. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow)

For a long time Kathryn Bigelow was a slightly above average B-movie director. With the exception of the fantastic Strange Days, Bigelow’s career came pretty close to workwomanlike. With The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, she’s developed her own voice, and a powerful one at that. Very few filmmakers can make 2+ hours of exposition this exciting, but Bigelow managed to make screenwriter Mark Boal‘s intricate script an excellent procedural.

6. Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (Lorene Scafaria)

Perhaps the most overlooked movie of the year is Lorene Scafaria‘s directorial debut. Seeking a Friend for the End of the World is an incredibly charming piece of work. It never gets too quirky or overly sentimental for its own good. We love the two leads, Dodge (Steve Carell) and Penny (Keira Knightley), and, by the end, the saddest part of the apocalypse is they don’t get to spend any more time together.

5. Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino)

It must be so easy for Quentin Tarantino, as nearly every scene of Django drips in meticulous coolness. How does he do it? If he was being modest, perhaps his answer would be good casting. With Django, he certainly brought something out of both Jamie Foxx and Leonardo DiCaprio; the former always felt like one of those actors who can’t fully immerse himself in a character, but he disappears in Django and while that’s never been a problem for the latter, he is unexpectedly able to crack a smile. DiCaprio relishes every single punctuation with villain Calvin Candie, and the same goes for Tarantino and the rest of his wild spaghetti Western.

4. Seven Psychopaths (Martin McDonagh)

Here’s the funniest and tightest script of the year, which won’t get a single ounce of awards credit. Martin McDonagh instantly became one of today’s most exciting screenwriters with In Bruges, but Seven Psychopaths showed he’s becoming a real visual storyteller. The scenes in the desert are vibrant, providing the action movie aesthetic the film’s hero/villain Billy (Sam Rockwell) wants his life to look exactly like. Seven Psychopaths is how a writer does meta without getting all smug about it.

3. Cloud Atlas (Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer)

By far the most flawed film on this list. We can talk all day about how some of the makeup isn’t always top-notch or how the movie can get too silly, but similar to most projects that aim for the sky, I will greet failures along the way. However, when it does grasp its lofty ambitions, the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer make a grand, mesmerizingly structured, and romantic movie about the power of love, evil, and all things life. What stops it from landing in pretentious danger zone is the fact the Wachowskis and Tykwer aren’t afraid to deliver prime spectacle over heavier thematic questions.

2. Looper (Rian Johnson)

Rian Johnson‘s last movie, the joyfully bittersweet The Brothers Bloom, wasn’t for everyone. With Looper, he’s crafted more of a crowdpleaser, while never forsaking his own voice, a style which he seems to be consistently sharpening. Looper is his most complete and satisfying movie, where everything falls into place just right. While a good amount of science-fiction films never go beyond their nifty set up, Johnson sidesteps that problem with dramatic questions, propulsive character-driven action, and two terrific anti-heroes: young Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and old Joe (Bruce Willis).

1. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson‘s tale of friendship feels five days long — rarely has that ever been a good thing to say, but it is in this case. As technically impressive as The Master and Anderson’s use of 65mm is, it’s Freddie Quell and Lancaster Dodd we’re memorized with, not Anderson’s camera. Anderson’s sixth movie isn’t an indictment of religion or cults, but a tragic friendship between Quell, who has no interest in life’s greatest questions, and a man, Dodd, who knows he has none of those answers.

John Fink’s Best Films of 2012

Observing current trends and the year in film vis-à-vis the current political landscape is something that’s difficult to do – I for one was shocked not much in the news was made, post-Sandy Hook of the opening of Jack Reacher (a film produced well before the horrific events that shook moviegoers internationally in Aurora, CO), yet I fear revisionist film scholars will point to this and draw conclusions. In the broader sense I do think 2012 was a brave and ambitious year for film – seeing Cloud Atlas and Killer Joe (which had a considerable release for an NC-17 rated film), along with films asking very hard questions (Detropia and Mea Maxima Culpa – on my list, and the conservative hit 2016: Obama’s America, which is not).

Another trend I observed fully was the arrival of DSLR filmmaking and its implications, specifically a trend at SXSW this year I dubbed “hipsters in the woods” – a growing number of filmmakers taking to the woods, often using available light to tell stories often about troubled relationships amongst mid-late-20-somethings. The kinds of films that will show up on Netflix instant watch in the next year or so. Cities like Detroit (2 on my list) and Pittsburgh are also in the spotlight more and more, not as surrogates for other cities but actual locations Hollywood is now setting films.

For me, there wasn’t one trend I observed specifically in the indie and doc world, although as blockbuster Hollywood cinema becomes more global, I agree fully with Brian Roan’s sentiment (expressed on The Film Stage Show) that the summer blockbuster is finding ways of being pro-American power without alienating the global market place, and thus instead of fighting an evil super power (well North Korea is always a safe villain) or ourselves, we might “aliens” hell bent on destroying the world. Here’s to a 2013 where we can continue to examine, like Detropia and Mea Maxima Culpa – the enemy within!

Honorable Mentions

Top Ten

10. Killer Joe (William Friedkin)

Here’s what you get when you take top-notch actors, a brilliant filmmaker and sharp source material. William Friedkin and Tracy Letts‘ latest collaboration is an explosive, violent and witty tale of revenge and stupidity deep in the heart of Texas.

9. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

Perhaps an arrogant title for reasons I will not give up, Holy Motors is certainly a wild ride, one you are best prepared for without any spoilers. Exposing the motor of “artifact,” here’s an entertaining, yet challenging film that offers one of the most refreshing experiences at the cinema this year.

8. Detropia (Heidi Ewing & Rachel Grady)

Detroit can be any town — the high tech industry could pull out of Austin, Buffalo could fall deeper into a depression, Hartford could loose its insurance companies. Detropia takes this approach: showing rather matter-of-factly what Detroit was, and what it is now: it’s a minor triumph as hipster artists move in to take advantage of cheap loft space and grow Detroit roots (what Nicolas Bourriaud called Radicant aesthetics) – but what makes this such an authentic portrait is the story of Black middle class life.

7. Searching for the Sugarman (Malik Bendjelloul)

The search for Rodriguez, a Detroit-based musician who finds little fame in the US, yet explodes as the soundtrack to the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. The film is a joy, telling the story of a man who lives, despite the odds a rather happy life in Detroit working in construction while his music lives on in South Africa.

6. The Kid with a Bike (Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne)

A touching and manic film starring by Thomas Doret as an orphan and Cecile De France as a hair dresser that takes him in, in a brilliantly acted and haunting drama by cinematic masters, the Dardenne brothers.

5. Argo (Ben Affleck)

Top-notch, white knuckle entertainment, Argo never lets up, retching the tension until its conclusion. Based on declassified CIA documents, Affleck does double duty as he stars as Tony Mendenz, a legendary CIA operative who extracts (via Hollywood movie magic) six American diplomats at the height of the Iran hostage crisis.

4. Samsara (Ron Fricke)

A beautiful 70MM epic from Ron Fricke (Baraka), chronicling the modern world in all its rituals from hollowed ground, disaster zones and industry.

3. Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino)

An epic ballet of violence, carnage and sharp dialogue. Tarantino takes dead aim combining witty shots evoking D.W. Griffith and John Ford, with sharp performances, making for one of the year’s most entertaining films.

2. Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God (Alex Gibney)

Gibney has been known to take on the establishment in the past, here he solidifies his place as the bravest documentarian working today – exposing the horrifying multi-century cover-up of pedophilia in the Catholic Church, giving voice to a group of deaf men who attempted to expose this matter in the 70’s. The conspiracy and cover-up goes all the way to the Vatican and Pope Benedict, in this explosive and important documentary.

1. Cloud Atlas (The Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer)

One of the most ambitious and skillfully executed movies ever made, Cloud Atlas is a carefully composed ballet defying space, time and genre (think The Matrix crossed with The French Connection crossed with The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel). It often draws non-linear emotional connections across multiple universes and running three hours, it wastes not a frame.

The Film Stage’s Best Films of 2012

[Jordan Raup] [Dan Mecca] [Nick Newman] [Raffi Asdourian]

[Danny King] [Jared Mobarak] [Jack Giroux] [John Fink]

Follow our look back at 2012: The Year In Film

What were your favorite films of the year?