In a medium founded on expanding one’s imagination and perception of reality, no genre does it better than science fiction. We’ve come a long way from the days when Georges Méliès took us to the moon, for today’s filmmakers look far beyond our universe and into the deepest corners of our soul to reflect the current society.

With the latest entry in the Star Trek franchise arriving in theaters this week, we’ve set out to reflect on the millennium’s sci-fi films that have most excelled. To note: we only stuck with feature-length works of 60 minutes or longer and, to make room for a few more titles, our definition of “the 21st century” stretched to include 2000.

Check out our top 50 below and let us know your favorites in the comments. We’ve also put the list on Letterboxd so you may keep track of how many you’ve seen.

50. The Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions (Lilly and Lana Wachowski)

I’ll ignore the wealth of received wisdom that’s surrounded these films for thirteen years and instead offer what’s earned: praise. Following The Matrix‘s lightning-in-a-bottle success, the Wachowskis crafted a two-part sequel expanding their original film’s strengths (aesthetic and action sensibilities, superb pacing, easily digestible philosophy) into the realm of be-all, end-all conflict. No matter the intensity and portent at its core, this duology makes great effort to balance in-the-moment pleasure with overarching narrative and theme. Where to start? The infamous rave sequence is a tactile, all-colors celebration of humanity intercut with a sex scene more attuned to sensory experience and emotional connection than almost anything else this century. There’s the extended, Lambert Wilson-delivered monologue on causality sandwiched between a) a plot-advancing exchange wherein Keanu Reeves must make-out with Monica Bellucci and b) a Cornel West cameo. There’s an understanding how words (“the Prophecy”) and voices speaking them wield a mantra-like power that dominates any other effect; but of course there are numerous CG images that either retain their awe or now charm in their somewhat-dated form. (Visible seams and all, the final Neo-Smith battle remains the greatest superhero-villain encounter ever put to screen.) Grand in every sense of the word, particularly side-by-side. Hence this pairing: treated as one entity (with a sanity-preserving intermission included), Reloaded / Revolutions is an epic of the highest order. – Nick N.

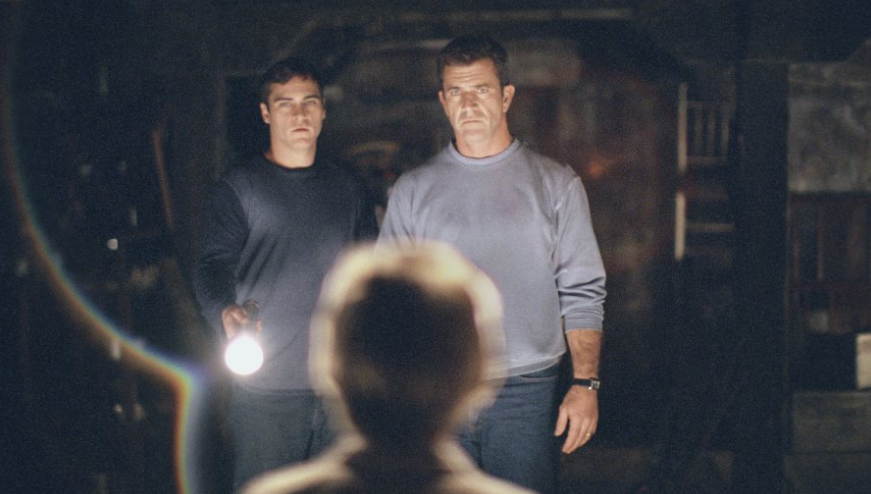

49. Signs (M. Night Shyamalan)

Signs represents a curious moment in the career of M. Night Shyamalan, as despite being a massive success, on display were some of the earliest examples of his future faults: the bizarre, darkly comic moments that seem tonally out of place; the forced twist at the end that exists solely because he’s M. Night Shyamalan; the hokey dialogue. And yet within the bubble of Signs, which exists mostly as a stylistic exercise in Hitchcockian thrills by way of an episode of The Twilight Zone, these future blunders mostly work. Part of it comes down to the performances: Mel Gibson and Joaquin Phoenix know how to handle the black humor in a way that Mark Wahlberg didn’t, for example. The idiocy of its twist ending is kind of irrelevant to the crux of this picture’s story, so it’s somewhat more excusable than people running away from trees. The score by James Newton Howard is eerie and striking, paying homage to Psycho with its assaulting theme. It’s Shyamalan’s last truly good movie, representing a strong balance of his eccentricities and stylistic quirks, and an unfortunate example of fine work being cheapened by all that came afterward: his subsequent films were so bad that it only caused people to reflect upon Signs with a harsher outlook. – John U.

48. Southland Tales (Richard Kelly)

Somehow more audacious than his feature debut, Southland Tales finds Richard Kelly spinning a thick yarn of post-apocalyptic sci-fi madness. At once extremely dense yet still thoroughly engaging on a level of pure simplistic entertainment, Kelly achieves a rare combination that makes for a special success. While certainly not for everyone, it stands as a testament to a modern director not satisfied with traditional narrative trappings, instead swinging — often wildly, sometimes flailing — at the far reaches of post-modernist storytelling as he tries to turn a mirror on society. Complete with unorthodox musical sequences, the world’s first car-on-car sex scene, and a cathartic, beautifully mad ending, Southland Tales is the realized vision of a true auteur. – Mike M.

47. Predestination (Peter and Michael Spierig)

The fraternal filmmaking duo Michael and Peter Spierig combine neo-noir style and labyrinthine storytelling for the tale of a time-traveling special agent (Ethan Hawke) who, while on the hunt for a terrorist, poses as a bartender in 1970s New York. Hawke might lead this mind-bending, Robert Heinlein-inspired thriller, but it’s his co-star, Sarah Snook, who steals the show as a brooding bar patron with a very complicated past. As the two protagonists talk over a long night of drinks, flashbacks and voice-over deliver one surprise after another, all of which culminate in an unbelievable twist ending. – Amanda W.

46. Midnight Special (Jeff Nichols)

Writer-director Jeff Nichols‘ thrillingly oblique tale of a father and his mysterious son leading the federal government on a cross-country chase, feels like old fashioned sci-fi storytelling at its most eerily engrossing. Beautifully capturing the spirit of the finest examples of the genre with its haunting sense of mystery and wonder, the film is anchored by David Wingo‘s marvelous score, and a handful of emotionally engaging performances from Michael Shannon, Kirsten Dunst, Joel Edgerton and Jaeden Lieberher. Nichols’ dryly taut screenplay bountifully rewards multiple viewings as the seemingly jargon-heavy dialogue often slyly supplies the audience with answers before we’re even posed the cryptic questions. Heart-wrenching in emotional impact, it masterfully weaves a grounded narrative around fantastic and extraordinary sci-fi concepts to tell an achingly tender story about a very special little boy. – Tony H.

45. The Road (John Hillcoat)

When most people think of science fiction, they picture futuristic cityscapes and bold adventures into the yawning abyss of space. The Road looks closer to home and asks one of the most depressing questions one can encounter when thinking of the future and the fate of our planet: what happens when it all dies? Entropy occurs when no new energy enters a system, and The Road – in washed out shades of grey and brown – posits a world in which entropy has taken hold. Nothing is growing, the sun is blocked out by dust, and the system of human kindness is winding down. Into this dead world the only new energy is the love of a father for his son. Whether that is enough to re-energize the system remains to be seen, but the idea remains and the visceral impact of the film and this world and its attendant horrors cannot be understated. – Brian R.

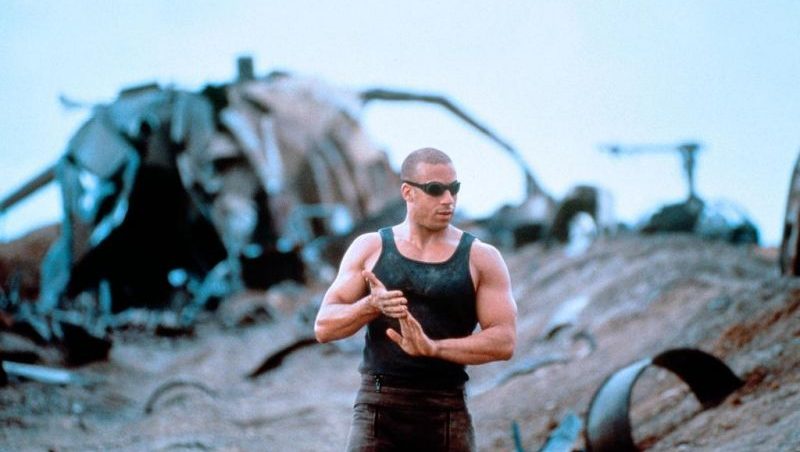

44. Pitch Black (David Twohy)

The movie that successfully pitched Vin Diesel as action star. As directed by B-movie auteur David Twohy, Pitch Black is a tight, scary creature feature with a head on its shoulders. Radha Mitchell works against Diesel’s antihero admirably, both leads immersed in some, impressive (if a bit dated) production design. Over 15 years later, the Riddick Trilogy (Pitch Black, Chronicles of Riddick, Riddick) exists as a somewhat underrated piece of sci-fi/fantasy storytelling. – Dan M.

43. Coherence (James Ward Byrkit)

The concept of a multi-verse has intrigued people since it first entered the scene. The idea that every choice on a quantum level results in a split universe being created means that there exist an infinite number of worlds in which things are either the same, similar, or wildly different. Coherence entertains this idea not through the eyes of scientists seeking it out, but through the eyes of dinner party guests grappling with its unknown consequences. A passing comment merges multiple realities onto a single street, and the guests at a supremely awkward dinner party have to decide how to keep themselves safe. known where they are, and to decide whether or not they even want to remain in the same place. It’s a devilishly clever film that starts as a taut thriller and turns into an existential horror film. – Brian R.

42. Contagion (Steven Soderbergh)

It’s hard to deny the haunting power of Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion. It’s a cold hard look at the bare facts of how efficiently a fatal disease can spread and instantly change the dynamics of our world while taking out half the population in the process. Featuring an ensemble cast who all deliver understated and subtle performances and a fantastic score by Cliff Martinez, Contagion’s real power comes from it’s raw fear of the unknown. Hats off to Soderbergh for not over-dramatizing his direction; the result is a hard-edged and profoundly frightening sci-fi (thanks to the invention of a fake disease) horror film that will leave you scramming for the hand sanitizer and a hazmat mask. – Raffi A.

41. The Lobster (Yorgos Lanthimos)

The Lobster is a bizarre film, which shouldn’t surprise anyone familiar with Yorgos Lanthimos’ previous work. To attempt to explain the story is futile, as it just sounds deeply silly: a man who has not yet found a life partner checks into a resort where, if he doesn’t find a mate within a short period of time, he will be turned into an animal of his choosing. The fact that he chooses to become a lobster is just one in a series of darkly funny moments that are played pitch-perfectly by a pot-bellied Colin Farrell, who gives his best performance here since In Bruges. Farrell has repeatedly been shoehorned into mainstream Leading Man Roles like Total Recall, where he consistently falters and is charmless, but it’s in these smaller and quirkier affairs where his strengths shine through and he tends to remind me of why he’s a great actor. The movie is alternately tragic and subversive, and humorous; it would be false to compare it directly to Dogtooth, except to say that the after-effect is similar: you’re left a little moved, a little bewildered, a little disturbed, a little buzzed off the laughs – and craving a second viewing. – John U.

40. Cloud Atlas (Lilly and Lana Wachowski)

Even a cursory glance at the book’s description will offer a good indication of how difficult a task it would be to adapt David Mitchell‘s Cloud Atlas. Consisting of six nested stories that unfurl across a span of thousands of years with a top-notch ensemble cast each playing several different roles, it’s a story blending mystery, comedy, sci-fi, and action filmmaking into one towering tale. Directed by Tom Tykwer, Lana Wachowski, and Lilly Wachowski, it’s a project that sounds as if it should be the basis for a Jowdorowsky’s Dune-like documentary about a failure to attain funding. Thankfully, Cloud Atlas was made into a rip-roaring adventure story of the highest caliber, keeping us thrilled and engaged with each plot strand, no matter how bizarre. Tykwer and the Wachowskis may be painting with broad strokes, but they’re immaculately placed, enveloping their audience in the sweeping scope of this grand tale. – Tony H.

39. The World’s End (Edgar Wright)

A long awaited pub-crawl slowly morphs into a fight against a robot-imposed Armageddon as Simon Pegg and Nick Frost re-team with Shaun of the Dead/Hot Fuzz director Edgar Wright for the conclusion to their beloved Cornetto Trilogy. The protagonists, adult males who attempt to recreate a nostalgic high-point from their adolescence, are all quietly miserable with their adult lives. Their fearless leader, Gary King (Pegg, who collaborated on the screenplay with Wright) is the least happy because in the passing years, he realized that his unfortunate life peaked while he was intoxicated in his teens. Gary has spent the last two decades re-telling the story of that fateful night, transforming it into the stuff of legends. However, until the violent hand of cosmic fate steps in, Gary King is merely a legend in his own mind. – Tony H.

38. Vanilla Sky (Cameron Crowe)

An ambitious remake of Alejandro Amenábar’s Abre Los Ojos and certainly Cameron Crowe’s strangest film, Vanilla Sky was released at a time when Tom Cruise was so popular that he could open a romance film about a murder in a chemically-induced dream-world and people would show up. The star leans into his good looks and charm here like never before, offering a performance that’s surprisingly self-aware. – Dan M.

37. Ex Machina (Alex Garland)

Between Siri and Cortana and Watson, the idea of artificial intelligence in our daily lives has gone from a creepy possibility to a banal and often frustrating reality. Likewise, humanoid robots are slowly becoming an accepted reality in all manner of fields. Ex Machina does the seemingly impossible by taking both of these well-trod ideas and extrapolating from their slowly evolving reality-based counterparts and making it terrifying again. It does this by asking a simple yet deeply unsettling question: what if you spend all of this time and energy just to create something that hates you? The answer gives us insights into how humanity influences its technological advancements, both for good and for ill. The worst part of what we make won’t be something we can’t predict, it will be the pieces of ourselves we give it. – Brian R.

36. The Man From Earth (Richard Schenkman)

Produced on a budget of $200,000, The Man From Earth quietly premiered at San Diego Comic-Con Film Festival in July 2007, where it went on to have a minuscule theatrical release a few months later. Soon after, an illegal copy of the film hit the internet, where it went on to explode, becoming a cult hit around the world. Scripted by the late Jerome Bixby before he passed in 1998, the small-scale film follows John Oldman (David Lee Smith), a university professor saying goodbye to his friends during a farewell party. They gather together and what follows is a fascinating discussion revealing that Oldman is a Cro-Magnon that has been alive for 14,000 years. If at its very core, the foundation of science-fiction is imaginative storytelling, The Man From Earth may be the genre’s purest example. – Jordan R.

35. Lucy (Luc Besson)

He may have found financial success with his screenwriting involvement in franchises like Taken and Transporter, but Luc Besson had hit a directorial rut. Enter Lucy, an unapologetically insane thrill ride that no summer blockbuster could quite match back in 2014. While some squandered their time with assertions over the lack of scientific accuracy, many of us enjoyed the director’s take on a superhero film — easily surpassing anything in Marvel’s output in the process — with a dash of The Tree of Life thrown in. Add a worldwide gross of nearly half a billion dollars, and it looks like I wasn’t alone in my unadulterated enjoyment. – Jordan R.

34. The Host (Bong Joon-ho)

Before he took on class warfare with his dystopian thriller Snowpiercer, South Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho may have singlehandedly reinvigorated interest in the monster movie with The Host. The 2006 film successfully melds human drama with rampant destruction in its depiction of a dysfunctional family forced to contend with a blood-thirsty monster inhabiting Seoul’s Han River. Though time has not been kind to the CGI beast, it’s worth overlooking this less convincing aspect in order to enjoy Bong’s expertly constructed, dazzlingly kinetic action set pieces. – Amanda W.

33. Star Trek (J.J. Abrams)

I don’t think I would necessarily dislike it, or what it represents in the realm of science fiction, but I’ve never really had the opportunity to delve into Star Trek. And that’s an important disclaimer, because for many viewers such as myself, J.J. Abrams‘ Star Trek was one of the few times that the series really managed to spread beyond the cult fanbase into a full-fledged blockbuster, and capture the imaginations of a wider audience. It’s completely understandable why that riled some long-time fans, but it also makes sense why Disney saw this and immediately pegged Abrams for Episode VII. It’s simply a damn fun movie, with great action, humor, special effects, and thrills (how’s that for a commercial soundbyte?). At the end of the day, even the biggest Star Trek fans have to admit that entries like Nemesis weren’t exactly keeping the series afloat at the box office or with the long-time fans, and the Star Trek reboot managed to slickly reinvigorate the series as a whole and bring new fans aboard. – John U.

32. Mr. Nobody (Jaco Van Dormael)

Why do we remember the past, and not the future? This is a question posed by director Jaco Van Dormael in his wildly ambitious existentialist journey, one of many that he isn’t afraid to face head-on. Mr. Nobody starts with an exhilaratingly disorienting and unforgettable opening sequence before shaping into a profound exploration of choices and regrets, forcing viewers to consider the path walked upon, and the one parallel, or forgotten that could have just as easily been taken. Stripping away its missteps, and taking it for all its ambitiously bold ideas and approach, it is hard to understate the simple beauty and tragedy of the film. It is peculiar, funny, sexy, and full of life. Perhaps most importantly, Mr. Nobody is like the human memory itself: a sometimes flawed, beautifully idyllic, and inevitably heartbreaking summation of our experience as human beings. – Mike M.

31. Attack the Block (Joe Cornish)

A hybrid, rated R mix of The Sandlot and Tremors, this British sci-fi horror comedy by newcomer Joe Cornish was a mild success that should have led to bigger and better things for the creatives involved as well as the actors. By now you’ve likely heard of John Boyega, but Cornish remains criminally unheralded for his work that has plenty of charm and fun, but isn’t afraid of getting violent and dangerous. The creature effects are also a huge reason why this adventure works and are perfectly nightmarish and cool at the same time, a crucial element combined with the thumping soundtrack. – Bill G.

30. Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Liman)

While Tom Cruise is no stranger to being a sci-fi spectacle star (as evidenced by other entries on this list), Edge of Tomorrow gave the spotlight to Emily Blunt as a new-age heroine who owns the role. The Groundhog Day-style of repeating the same day over and over is also played to its full effect, boosted by immersive action that does a wonderful job of selling the alien invasion as a legitimate threat. Edge of Tomorrow (or, rather, Live Die Repeat) may not have gotten its due in its initial theatrical run, but this is a high-concept sci-fi that legitimately soars during endless rewatches. – Bill G.

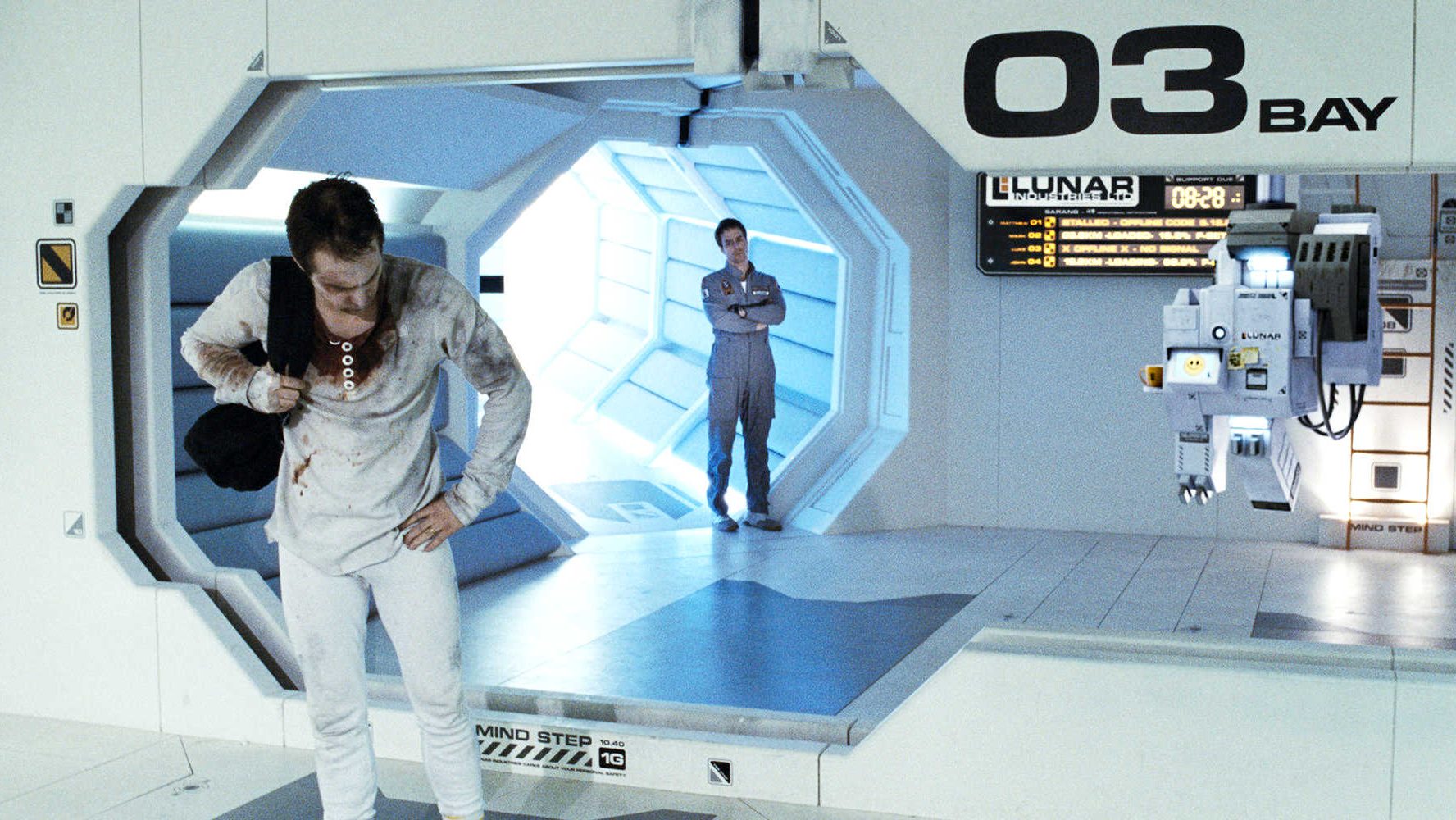

29. Moon (Duncan Jones)

Raised by one of Clint Mansell’s most memorably melodic scores – short of the inescapable “Lux Aeterna,” the legato piano trills of the main theme might be the biggest ear worm of his formidable career – Duncan Jones’ ambitious debut, Moon, is an impressive piece of production design and character economy. Propelled by an anxious, shadow mirrored performance from Sam Rockwell, and a structure that peels back reveals without aggravating the carefully cultivated atmosphere, Moon is a tricky balancing act – and a calling card for one of this century’s most slippery, developing filmmakers. – Michael S.

28. The Prestige (Christopher Nolan)

The Prestige is relatively light work by Christopher Nolan, a thematic downgrade from the serial killer cat-and-mouse game of Insomnia; the wonderfully intoxicating and heavy Memento; the unnerving Following; and yes, even the psychological exploration of Bruce Wayne’s demons in Batman Begins. I think when looking back at his career thus far, it stands out as the least substantial in many ways – and yet it is also one of his most memorable films, as one can sense a bit of freedom afforded him by the success of Batman. This is Nolan unshackled from the studio constraints of a comic book tentpole, having fun and delivering a clever and crafty yarn. The performances from all involved are wonderful (I still rank it as one of Hugh Jackman’s best), and the tonal shift towards earnest sci-fi as the picture progresses – the kind of tricky balancing act that could derail a lesser filmmaker – results in a surprisingly moving ending, one where everything we think we know is turned on its head and a bit of tragedy seeps through the picture. The Prestige is Nolan pulling a trick over on his audience just as expertly as Michael Caine’s character explains in the film itself, and yet never once do we feel cheated. – John U.

27. Primer (Shane Carruth)

In delivering the undeniably pleasing (if eerie) experience of seeing history realign itself despite human characters’ attempts to change it, time travel films typically gloss over the logistics of navigating space-time. Primer, on the other hand, obsesses over the technicalities. Drawing on the math and engineering background of Shane Carruth — who served as director, producer, writer, editor, composer, and lead actor—the film leads us to imagine what, exactly, the most rational among us would do if we accidentally discovered how to invent a time machine. Miraculous for a $7,000 film filled with jargony dialogue exchanged in nondescript rooms, Primer is enormously suspenseful, because it’s one thing to see a thinly sketched action hero get duped by the immutability of time, and quite another to see sensible, exactingly meticulous planning meet the same end. – Jonah J.

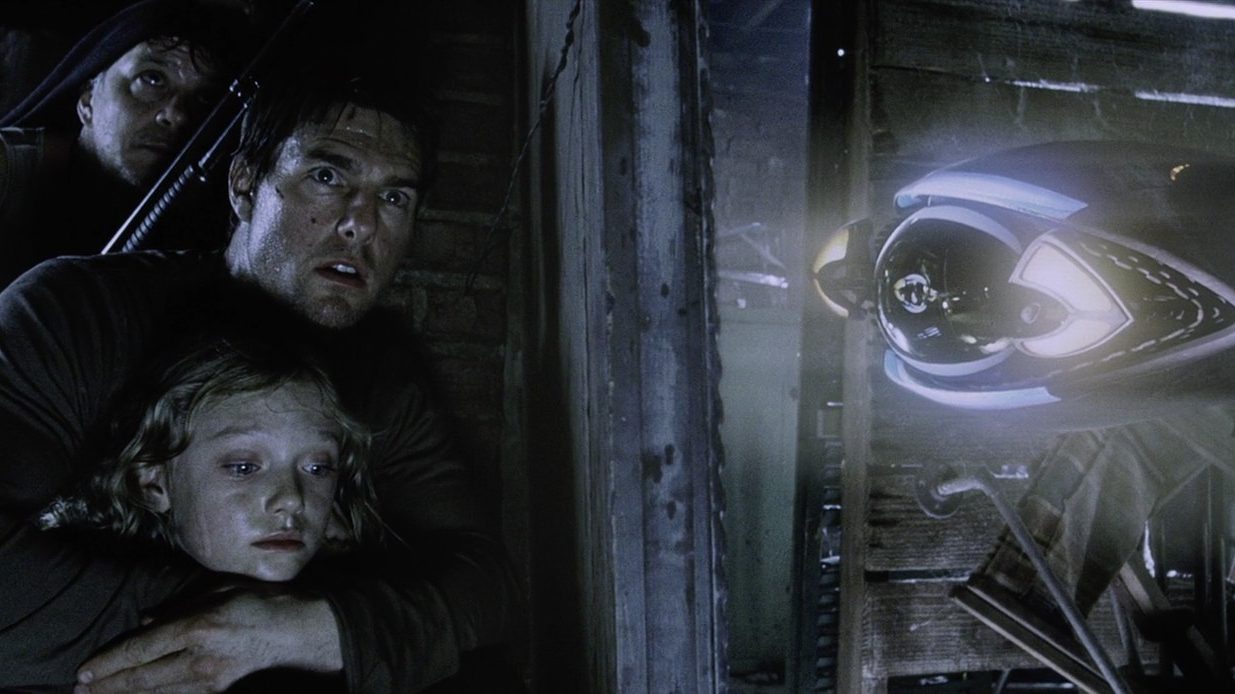

26. War of the Worlds (Steven Spielberg)

It’s one of the very best films Steven Spielberg ever made — razor-sharp in its build-up, bold in its elision of details, terrifying in its plausibility (or reliability, if nothing else), admirably bleak in its vision of humanity teetering right on the edge of its extinction — until a Tim Robbins-dominated third act that compacts a film of endless possibilities. Yet even War of the Worlds’ more slippery directions evince a creative boldness, a vitality that’s still put into effect more often than not — e.g. the extended take inside the basement, the brutality of man-on-man violence, the sequence that casts the world’s most recognizable actor as a suicide-bomber — for me to already start backpedaling on my qualification. And, yes, the happy ending is just fine. After everything else that’s happened in the preceding 105 minutes, you’re going to start qualifying something as impossible now? – Nick N.

25. District 9 (Neill Blomkamp)

A problem often brought up by critics of science-fiction — especially many recent works — is that story and character get lost in an array of dazzling spectacle and simplified expository bouts of the science. While still retaining textured, wonderful sci-fi imagery, District 9 is a through-and-through character piece. Charting the transformation of a government employee from coward to meekly heroic (a wonderful turn from Sharlto Copley), while simultaneously serving as a satire on the state of affairs in South Africa, Neill Blomkamp‘s debut is a thoughtful, visually stunning work that never forgets the humanity amongst the aliens and explosions. – Mike M.

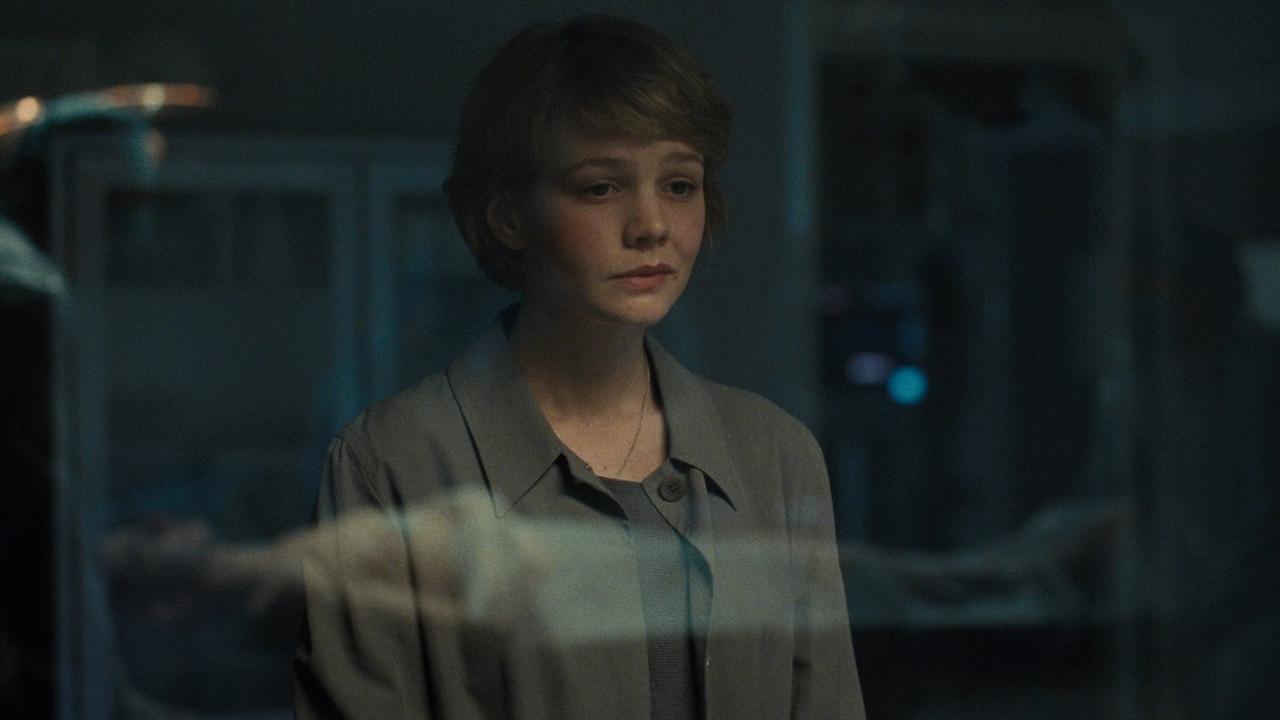

24. Never Let Me Go (Mark Romanek)

There’s a case to be made that Mark Romanek’s 2010 film, Never Let Me Go, isn’t science-fiction. An adaptation of Kazuo Ishugiro’s 2005 novel, Romanek does very little to tip the film’s hand toward its genre leanings, focusing on the burgeoning love triangle between three students at the gentile, buttoned-up school of Hailsham. There’s only glimpses of the horror of the future outside the gates. But underneath the mannered, layered performances by Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield, and Keira Knightley, there’s a prevailing interest in the genre’s themes of pre-determination, the nature of dignity, and a world where an idealized future is just out of reach. – Michael S.

23. Cloverfield (Matt Reeves)

Science-fiction films don’t get much more immersive than Cloverfield, Matt Reeves‘ thrilling feature debut, putting us directly into the shoes of an alien invasion. One of the rare cases in which intriguing, tight-lipped marketing actually delivered on its promise, this sci-fi found-footage thriller has memorable setpieces at every turn, complete with a sense of genuine panic, a feeling that other post-9/11 films often render as exploitative. Little did we know at the time of its debut (or even last year), it also serves as the ideal franchise starter as it’s able to splinter its stories in countless directions and forms. – Jordan R.

22. Solaris (Steven Soderbergh)

The idea of following in the footsteps of Andrei Tarkovsky would be an inconceivable feat for most filmmakers, but in Steven Soderbergh‘s case, he had his own reasons for providing a new take on Stanisław Lem‘s sci-fi novel Solaris. While the 2002 George Clooney-led film received a divisive critical response, audiences were less than enthused, as it received the infamous “F’ CinemaScore — although, one can hardly be surprised, considering its marketing sold an action-suspense thriller from its executive producer James Cameron, the man that brought you Aliens and the Terminator series. As it recently passed its 10-year-anniversary, I still find a great deal to love in Soderbergh’s take, which delivers a striking, emotionally resonant romance, a distinct, worthy deviation from Tarkovsky’s meditative masterpiece. – Jordan R.

21. Inception (Christopher Nolan)

Inception is one of the most ambitious blockbusters of all-time, and surely never would have been made if not for Warner Bros. trying to keep their Dark Knight director happy by throwing money at him to bring a passion project to life. Its subsequently enormous success just goes to show that sometimes the concept of dumbing down material in order to appeal to wide audiences isn’t necessary, because on paper this would be much easier to sell as a low-budget, arthouse movie, and if Christopher Nolan had shopped this around as a $200 million picture after making Insomnia he would have been laughed out of town. By this point, everyone knows the twisting, labyrinthine storytelling mechanisms that Nolan employs here; there’s no point in repeating them. What I found upon a recent viewing is how well it all holds up, even that trailer with the braam noise that ended up becoming the blueprint for almost every single Epic Blockbuster in the last few years. At the end of the day, considering its status as a summer blockbuster, Inception stands tall as a cerebral experience that doesn’t talk down to its audience. It just happens to have car chases and explosions, and a finale that at times feels like Nolan auditioning for a Bond movie, which we’d welcome. – John U.

20. Beyond the Black Rainbow (Panos Cosmatos)

Well, I might be wrong. I haven’t seen Beyond the Black Rainbow since its “international premiere” at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival, and my perceptions and tastes have, I think, changed a fair amount in that time — which isn’t even to account for the fact that it’s been more than five years. But that doesn’t mean I’ve forgotten much of the movie in that time, be it in the form of individual shots or jump scares, a distinct cinematographic palette, the fantastic score by Sinoia Caves, or the fact that its sci-fi qualities are best underlined by how little of its concepts are laid-out and how little that lack hurts the experience at hand. I’ll say this much: if giving Beyond the Black Rainbow another look meant Panos Cosmatos could start shooting a new movie, I’d be ordering a copy right now. – Nick N.

19. Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly)

One of the most audacious, dizzying feature debuts in recent memory, Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko has garnered a strong cult following for a damn good reason. A favorite of mine as a teenager, it is only upon a recent revisit that the sheer achievement of Kelly’s mesmerizing, unnerving calling card has become clear. It is a masterclass in atmosphere, lulling viewers into its clutches with oozing cinematography, spectrally seductive sound design, and a young Jake Gyllenhaal’s stupefied, haunted performance. Its unhinged, metaphysical plotting is coupled with some truly unforgettable imagery — namely in a movie theater — and genuine levity amongst the disheartening ruminations of its protagonist that every living creature on Earth dies alone. – Mike M.

18. Looper (Rian Johnson)

Cultures that have no tenses to delineate variable points in the past of the future make better choices. If someone only thinks in the present tense, they cannot dissociate themselves in the now from themselves in the future. Smoking, bad eating habits, destructive behavior – we like to imagine the effects of these poor choices impacting some shadow self who doesn’t exist yet and is not us. Looper, by writer/director Rian Johnson, takes this idea and envisions it magnificently. A young hitman must hunt down and kill his future self in order to save his own life in the present day. It’s a twisted, brain-bending narrative trick that uses science fiction technology to tell us something about ourselves and our relationships to both time and… ourselves. – Brian R.

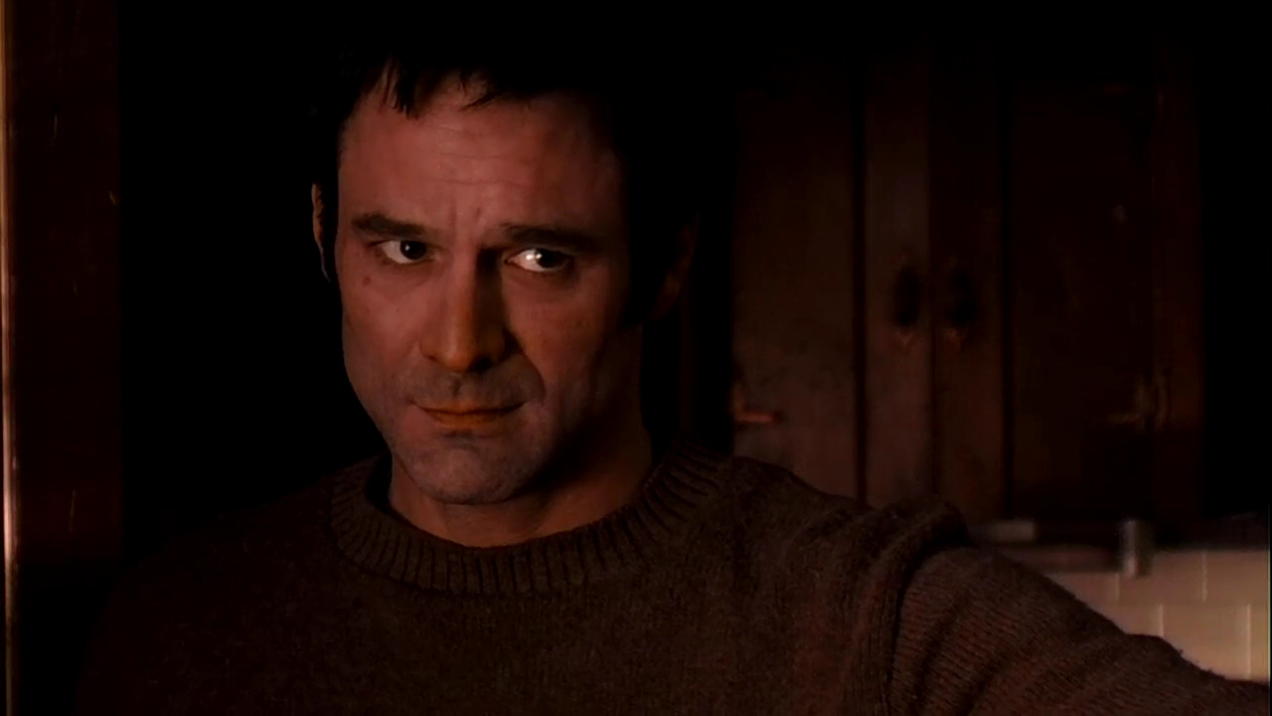

17. The Mist (Frank Darabont)

One of the great pleasures of any speculative or science fiction story is how they can put people in strange, unforeseeable circumstances and observing how they act. A weird device can be conjured up to alter reality, and through this device an artist can tell a tale that reveals something about mankind, using science fiction trappings to tell a very moral tale. The Mist, another Stephen King adaptation from Frank Darabont, flirts with the idea of portals to other worlds, but only for long enough to explain why a small New England town has been overrun by horrible monsters. Once those monsters are in place, The Mist turns its eyes from science fiction to existential fact. People confronted with the unknown and robbed of agency will grow fearful, and authoritarian regimes based on rigid dogma will fill that vacuum. Like any good science-fiction film, you can look at The Mist, and nine years later draw a direct parallel to our own uncertain present. Let’s just hope real life has a more optimistic ending. – Brian R.

16. Her (Spike Jonze)

Our computers and our phones are pretty much one nowadays. Our friends in the virtual and physical spheres are both equally as important to us. The more we create and invent the less we find ourselves beholden to our old concepts of rigidity of utility. A phone can be our primary computing device; a person we’ve never met can be our best friend. Merge those two concepts and add in a dose of our nascent interest in artificial intelligence, and you have Her, from writer/director Spike Jonze. After Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) installs a new AI operating system on his networked devices, he finds himself slowly falling in love with a personality who is as real to him as the writers of this list may be to you. Its a far out idea grounded in our very real, very new reality. – Brian R.

15. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg)

Steven Spielberg‘s profoundly emotional adaptation of Brian Aldiss’ Supertoys Last All Summer Long was a project originally developed by Stanley Kubrick. Abandoned due to the technological restraints of the early ’90s, Spielberg began working on the project shortly after Kubrick’s death in 1998. At the time of it’s release, some critics were left unmoved by the way the film twisted tones, mixing Spielberg’s inherently warm sentimentality with Kubrick’s detached intellectual coldness, as if either of these master filmmakers were thematic one-trick ponies. Far from it. What begins as a chillingly cerebral cautionary warning becomes a haunting fairy tale-esque meditation on the nature of existence. Wondrously imaginative and often disturbingly prescient, A.I. Artificial Intelligence is a intensely moving examination of the enduring strength of love, played out against an increasingly gorgeous dystopian backdrop. – Tony H.

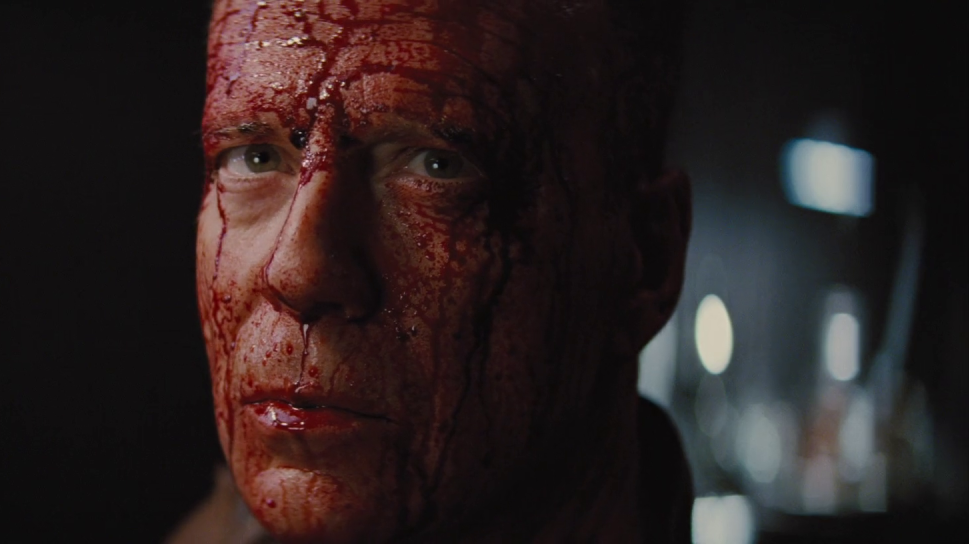

14. Hard to Be a God (Aleksei German)

A scientist from Earth, Don Rumata, travels to an alien planet where the population has become mired in the middle ages, the majority are seemingly happy to exist in chaotic slime-coated ignorance. They’ve even begun the purging of intellectuals, hideously burning scholars alive and drowning professors in overflowing latrines. Among these deranged citizens, Don Rumata lives like a god while the surrounding society slowly inches toward a hellishly inevitable collapse. Filmmaker Aleksei German shot this sprawling and twisted sci-fi masterpiece over the course of seven years, before passing away prior to the completion of the six-year editing process. Eventually completed by German’s wife, screenwriter Svetlana Karmalita and his son Aleksei Jr, the film is one of the most divisive and challenging labors of love in cinema history. Based on a novel by the Brothers Strugatsky, who also authored Roadside Picnic, which inspired Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Hard to be a God is a hypnotically visceral assault on the senses, placing the audience at ground zero to witness the ensuing madness as the landscape spirals out of control. – Tony H.

13. Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-ho)

Bong Joon-ho’s English-language debut unfolds around a none-too-subtle central metaphor — a post-apocalyptic train whose compartments are physical analogues of society’s socioeconomic strata — but this plot device is central to the film’s effectiveness. The train’s structural linearity proves the perfect platform for a similarly streamlined narrative that observes as revolution sweeps from the impoverished caboose to the engine room that powers the entire structure. As action cinema, Snowpiercer finds poetry in the simplicity of this tale of means and ends; as political allegory, the film’s narrative linearity conveys the social subject’s inability to see outside the system they inhabit, as the YouTube reviewer Nerd Writer pointed this out in his excellent video analysis. Lastly, the plot’s straightforwardness often guides our attention away from plot altogether — we grasp the uncomplicated narrative in an instant and henceforth acknowledge its existence almost solely in an unconscious fashion. Instead, our focus is redirected to the film’s Kubrick- and Gilliam-inspired art direction, which transforms the train’s interiors into a mobile museum of wonders at once bizarre, horrifying, and beautiful. – Jonah J.

12. Timecrimes (Nacho Vigalondo)

Some of the best, most twisted minds come from outside the United States and this film announced the break-out of Spanish filmmaker Nacho Vigalondo as someone to watch for years to come. Smartly written sci-fi is difficult to pull off, but make that science-fiction into a murder thriller with legitimate time-travel aspects and you have a real head-trip. Thankfully, Vigalondo manages to juggle all of this with a mature, fun sense of humor that will draw one in from its opening moments and never have one lose focus. – Bill G.

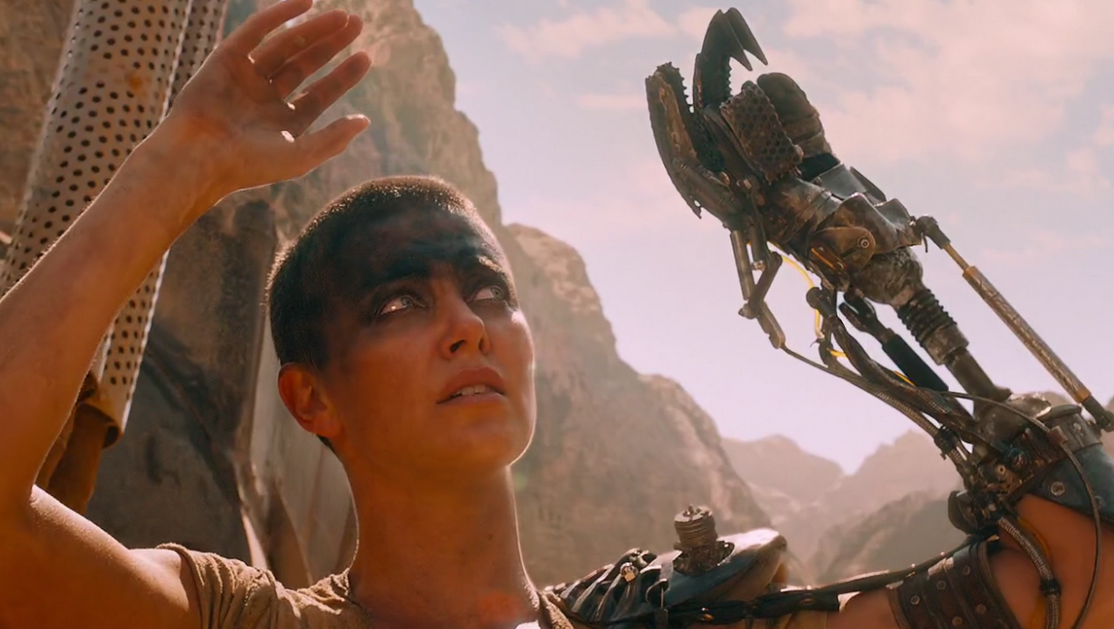

11. Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller)

The fourth entry in George Miller‘s Mad Max series is sci-fi tossed back into the stone age, where arcane technology fuses with blood and sand on the Fury Road in a fiendish struggle for survival. Humanity withers without available water in this post-apocalyptic wasteland, forcing thousands under the patriarchal command of Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne), who controls the aqua life-source of the entire Citadel. In their attempt to carry on, these men and women created a poisonous new Frankenstein world out of the previous one’s rubble. It’s the unlikely pairing of Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy) and Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) that revives a feeling long thought extinct: hope. While admittedly light on stereotypical science fiction accoutrement, the densely layered world and eye-popping kinetic propulsion of narrative found in Mad Max: Fury Road makes for an iconic and essential addition to any discussion of this millennium’s greatest sci-fi films. – Tony H.

10. 2046 (Wong Kar-wai)

So large is In the Mood for Love‘s place within contemporary cinephilia that it can be somewhat easy, even among Wong Kar-wai devotees, to forget its rather remarkable, in-many-respects-just-as-fine sequel, 2046, which simultaneously resembles its predecessor in rather exact ways and uses said predecessor’s emotional fallout to create an ultra-futuristic landscape. This is perhaps the closest we’ll ever got to Wong’s sci-fi movie, and its rather thorough display of colors, particular placements of the camera to wring maximum emotional resonance, step-printed photography, and oblique narrative (both the future segment itself and within the surrounding film) make it a perfect entry – so perfect, in fact, that I can’t help but wait for a full-fledged version. – Nick N.

9. Minority Report (Steven Spielberg)

Steven Spielberg was in top form when he helmed Minority Report, a high-concept, high-wire neo-noir that remains one of the new millennium’s snazziest blockbusters. Playing yet another version of his improbably athletic onscreen self, Tom Cruise is a police chief on the run after his “Pre-Crime” law enforcement program implicates him in the future murder of someone he’s never met. This doozy of a premise asks us to ponder the ethicality of jailing would-be criminals based on not-yet-perpetrated crimes and, by extension, the question of fate itself. Is this system flawless or irreparably flawed? Can Cruise’s hero not kill his supposed victim? Minority Report is popcorn cinema bold enough to wax philosophical in these ways even as it pushes ever-forward through visual virtuosity and a pleasingly twisty storyline. – Jonah J.

8. The Fountain (Darren Aronofsky)

Death is the ultimate villain. It has no conscience, it has no compassion, and it has no sense of justice. It comes for all and takes all with nary a care for time or place or circumstance. The story of The Fountain, from writer-director Darren Aronofsky, follows a man who grows tired with the tyranny of death and seeks to destroy it. Told through literal fantasy, cutting-edge medical science, and fantastical science fiction, his journey takes him to the edges of the earth and cosmos. What is amazing is how this film walks up to the edge of medical and astronomical science and then uses them as a means of creating a very internal revolution for a single man. Death is not the end; it is the road to awe. – Brian R.

7. Melancholia (Lars von Trier)

The end of the world is here, but the characters in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia can’t help but make it about themselves. In the second of his “Depression Trilogy,” and one of the most potent portrayals of mental illness’ daily effects from the past few decades, von Trier honors and judges these characters in their final fits of narcissism. For Justine (a career-best Kristen Dunst), the end is a sweet, caressing lullaby — a confirmation of her most inalienable beliefs. Meanwhile, Claire’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg) panic attacks ebb and flow with the accuracy of her husband’s scientific calculations, and in a mordant touch — her personal estimations with a coil of wire. Doom rarely feels so inevitably poetic. – Michael S.

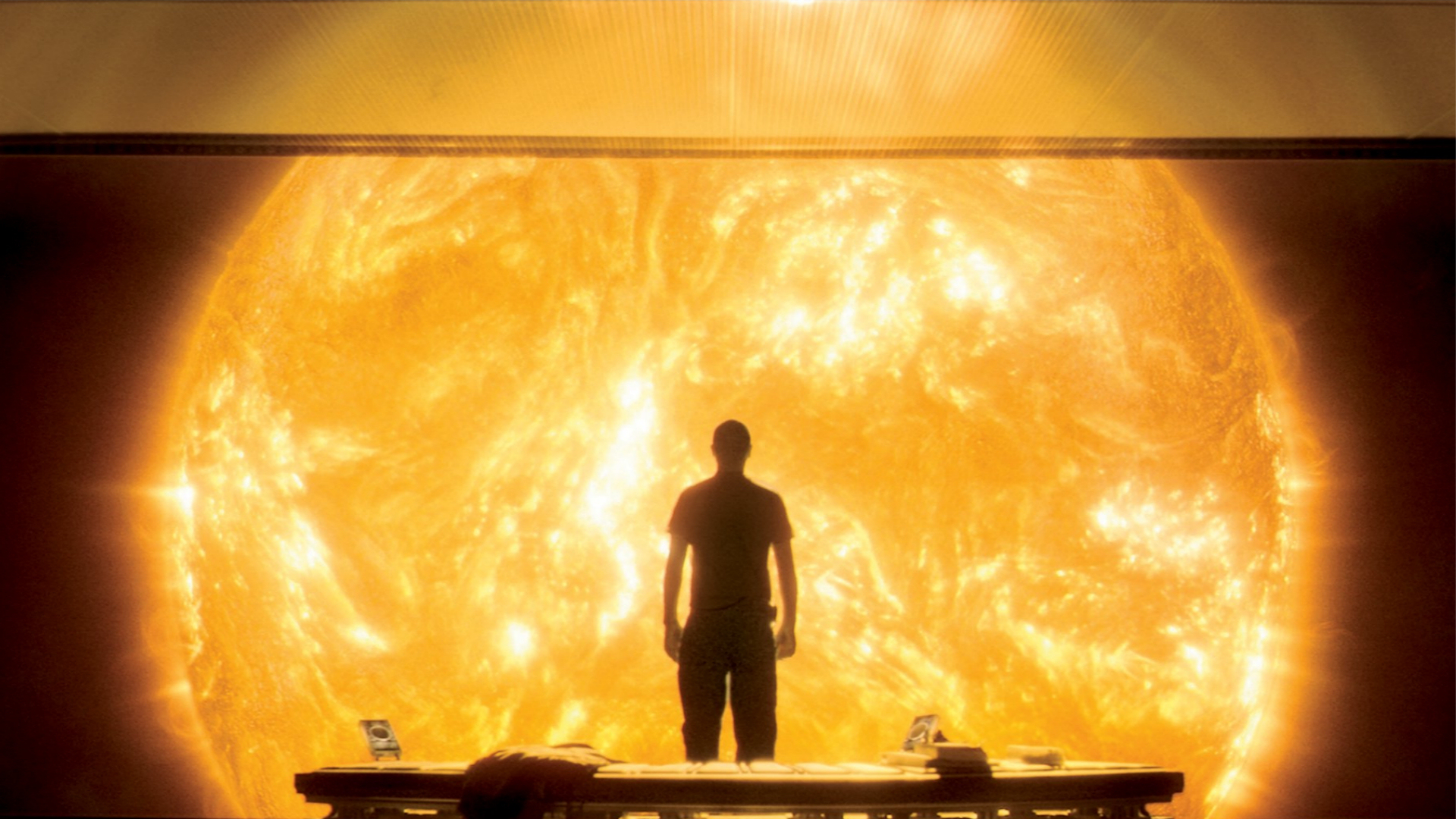

6. Sunshine (Danny Boyle)

A lot of science fiction films are so caught up in ideas that they don’t really have time to focus on details of the science they are exploring from a purely theoretical or concrete way. Sunshine (written by Alex Garland, who would go on to direct another entry here, Ex Machina) is a story of global cataclysm told almost entirely through the eyes of people who are not on earth. The death of the planet is an abstract concern as we, the audience, are shown the effect of extended space travel, the importance of our nearest star, and the almost incomprehensible scale of that same star. Every fact regarding the sun is so mind-blowing that it makes even the more banal parts of our days a source of awe and mystery. Space action and slasher trappings aside, Sunshine is a true celebration of the scientific method and the truth of our physical reality. – Brian R.

5. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer)

There was a mystique that was hard to escape when Under the Skin finally made its way to screens. The modestly budgeted sci-fi thriller, which garnered much anticipation in certain circles, has little expositional dialogue and focused on an alien that was preying on men using the body of Scarlett Johansson. Even the production was pulled off in a rogue way by filming with unsuspecting locals in Scotland. The end result is a truly eerie and stunning work of boundless imagination and flawless execution that shows, when given creative freedom, the closest thing we’ll get to the realm of Stanley Kubrick. – Bill G.

4. Upstream Color (Shane Carruth)

Nature. Technology. Humanity. The intersection of these elements is where we find the best science fiction, the stories that truly wrap in the totality of human experience and social understanding to create something special. To explain how Upstream Color, from writer-director Shane Carruth, manages to weave these things together would rob its audience of one of this film’s great joys. Suffice it to say, Upstream Color paints a tapestry of experience and life and the cycles that bind us together that will alter the way one looks at the world and their place within it. – Brian R.

3. Holy Motors (Leos Carax)

It’s a bit eye-rolling, this “cinema is like the most amazing sci-fi creation of all” idea, and Holy Motors is more than willing to poke fun at this while embracing its medium’s incredible possibilities. Leos Carax‘s goodbye to (physical) film is only a true genre entry at the most necessary moments, utilizing the bizarre, inconceivable, and their many possibilities when necessary — which doesn’t at all discount its place, mind — until the final sequence, talking cars and all. And, as it goes without saying, Denis Lavant is more thrilling than any alien creature or computer-generated sight. – Nick N.

2. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry)

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind plays out a fantasy many people have of erasing past regrets and then makes us witness the loss we would have experienced had our wish actually been granted. The film’s premise is one for the ages: a man in an unhappy relationship discovers that his girlfriend has had all memories of him wiped from her mind, so he decides to undergo the same operation himself. As his past with her grows foggier and foggier, however, he starts remembering the joyful moments in addition to the painful ones and realizes that all will be lost with the operation’s completion. Perfectly acted by an uncharacteristically mellow Jim Carrey as the amnesiac protagonist and Kate Winslet as his girlfriend, Eternal Sunshine is a beautiful treatise on love, and possibly one of the saddest films ever made. – Jonah J.

1. Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón)

Some of the best sci-fi stories ask one simple question and then imagine a world in which that question becomes a real concern. What happens when the sun dies? What happens when AI becomes indistinguishable from a person? Children of Men, flawlessly directed by Alfonso Cuarón, asks a question that is painful to consider and even more painful to observe: what happens when people can’t reproduce? The world that is created in the wake of this question is one in which hope and progress have died together, the last vestiges of society and technology crumbling simultaneously. But, as with all science fiction that truly endures, Children of Men finds salvation within the only place it could remain, even in the worst of times: the heart and soul of humanity. – Brian R.

Honorable Mentions: There was much division amongst us over Christopher Nolan‘s Interstellar and James Cameron‘s Avatar, while Duncan Jones‘ Moon follow-up Source Code nearly made the cut as did Splice, 10 Cloverfield Lane, Guardians of the Galaxy, Frequency,The Adjustment Bureau, CJ7, The Hitchhiker’s Guide the Galaxy, Serenity, Trollhunter, and About Time. Smaller-scale sci-fi like The One I Love, Ink, Monsters, and Another Earth left us equally impressed.

We also considered entries such as Skin I Live In, Gravity, Enemy, Idiocracy, and Battle Royale, but they either fell more into other genres, or had none of “fiction” to go with the “science.” The same goes for more fantasy and/or horror films such as Pan’s Labyrinth, Godzilla, Lord of the Rings, The Cabin in the Woods, etc.

Lastly, in order to mention more films here, we stuck to strictly live-action, so see below for out thoughts on Wall-E, A Scanner Darkly, Titan A.E, Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, Spirited Away, Monsters, Inc., and more great sci-fi animations.

The 50 Best Animated Films of the 21st Century Thus Far