Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2022, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

2022 was a year where lists were discussed a lot. Sight and Sound released their once-in-a-decade poll, which I unexpectedly and luckily got to participate in. Is the act of list-making frivolous? Some might think so. Others may consider it is absolutely necessary to canon-forming and an indispensable part of the discovery of new cinema. One thing is certain however: the idea of lists to the general public seem to be seen as valuable only in their ability to justify or reinforce already-held opinions. In the internet age of exposure to unsolicited opinions about the arts, the culture has retracted back to needing opinions validated over and over again rather than open to being challenged in the aim of discovering something new. In my lists of recent, very purposefully, I have taken the approach to choose movies I feel haven’t been mentioned enough, but also are good enough that I will carry them in memory into the future. So I’ll keep my naïve optimism that my list will get people to seek these movies out.

10. Wet Sand (Elene Naveriani)

After the death of her father, the estranged Moe starts to immediately feel the hostility of locals to her progressive, city-born lifestyle. She delivers the same hostility right back. Naveriani’s Wet Sand is a quiet fish-out-of-water story, but one that rumbles with a fury underneath that the movie is in no hurry to unearth. It understands that prejudices and hatred stem from insecurity and a stubborn attachment to fake rules that are being threatened by fake enemies.

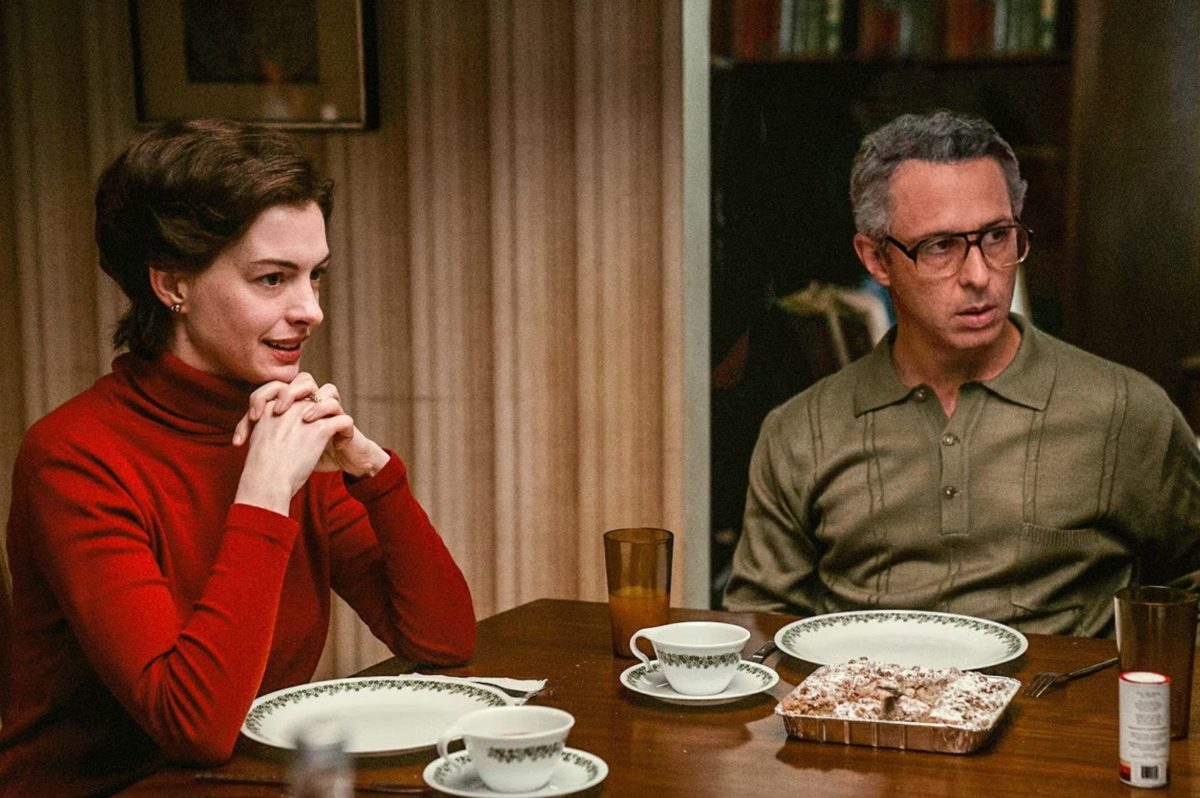

9. Armageddon Time (James Gray)

In a year of many self-reflective films from filmmakers, I’m not sure any hit quite as poignantly as Armageddon Time. It paints such a vivid picture of a group of people, both adults and kids, thoroughly confused by the world they inhabit. They all balance and dodge multiple obstacles, but the adults constantly showcase a phony grasp of the reality of things. It is Paul, at the end, who walks a resolute path away from the hamster wheel his family tries to get him on. It’s a path that turns his back on the country he feels failed him. More and more people are feeling the same.

8. Captain Ahab: The Story of Dave Stieb (Jon Bois)

Bois’ cinematic landscapes attempt to stir emotions through the layering of graphical data. In no video film of his does he do this better than the “Perfect Game Towers” he employs in Captain Ahab. Dave Stieb’s quest to pitch a perfect game becomes a collection of obelisks left unfinished, open sores in the cyberspace of Bois’s 2-dimensional frame. The Moby Dick metaphor that runs throughout the movie is one that builds organically, almost unnoticed until the big “moment” that takes your breath away.

7. Jackass Forever (Jeff Tremaine)

After years of getting hit in the nuts, the new edition to the Jackass franchise has introduced newly innovative and creative ways for its cast to… keep getting hit in the nuts. This is a movie and series that refreshingly and defiantly understands its own formula and aside from higher budgets and the knocking of father time changing a few things around, keeps the same energy it had at the turn of the millennium. Any fears of the culture around comedy having changed over this still-young century is washed away as you watch Steve-O cover his genitals in bees and Johnny Knoxville used as canon fodder into a lake.

6. The Banshees of Inisherin (Martin McDonagh)

I was surprised by McDonagh’s ability to commit to the depravity of this film while also maintaining its nervous comedic premise. Friendship is a strange thing and for Padraic and Colm it becomes an existentialist battle about the purpose of life, the imminent reality of death, and the struggle to leave anything of value behind. Its quaint but tragic setting is like a sinkhole, sucking its residents in deeper and deeper into a sense of meaninglessness and daring anyone to leave. By the end of the movie, you feel like you need to seize on every comedic moment, laugh twice as loud, and take advantage of the opportunities to be happy, because an unavoidable dark void is staring you right in the face.

5. Lingui, The Sacred Bonds (Mahamat-Saleh Haroun)

State oppression in Haroun’s films is not explicit, but committed in shadows, at night, and through stories and rumors. They are also nearly wordless. The operators of the state take their victims quickly and then they disappear into the dark. The peripheral threats are what turns Lingui into a sort of heist movie about abortion. The characters go through secret alleyways, having meetings in hushed tones, find themselves preparing to get raided by police at any point. Haroun’s depiction of Chad is equal parts affectionate and sinister.

4. Ariyippu (The Declaration) (Mahesh Narayanan)

An unexpected tech-thriller from India, Ariyippu is a devious and winding slow-burn in the mold of Cristian Mungiu. Narayanan weaves technological voyeurism and corporate corruption to excavate the subtle threats within the worker-employer relationship as well as the ways they seep into disrupting domestic life. This is a movie with many ideas on its mind and its formal structures are aimed at every nook and cranny of the “workplace” as a place of unrelenting tension and has the feel of a guillotine hanging by a thread over your head.

3. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (Laura Poitras)

The past and present moment, as captured through the visions of two artists. On one hand, Nan Goldin’s photography in 1980s New York shines with the vibrancy of a particular moment in time, a slideshow of people’s lives, characters to some, mirror reflections to others, but alive in the still images that she so keenly captured with the camera. Then, the artist herself is captured on camera by documentarian Laura Poitras, in a present struggle of protest against the Sackler family and their dark involvement with the opioid crisis. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed seamlessly ties two eras of Nan Goldin’s life together to create a portrait of an artist who is always awake and aware of the time she’s in

2. Mad God (Phil Tippett)

Phil Tippett’s Mad God strips away intention, forgoes puzzles, and decides to do things the hard way––for the art. His lifelong passion project drops us, along with the titular “assassin” character, into a hell world beyond our wildest nightmares. With the studio mandates that everything has to tie into something else, it’s refreshing to witness a stark vision where the narrative map literally disintegrates and we’re left fending for ourselves. We don’t where we’re going; we don’t know where the film is going. All we can do is hang on and witness in wonder and terror.

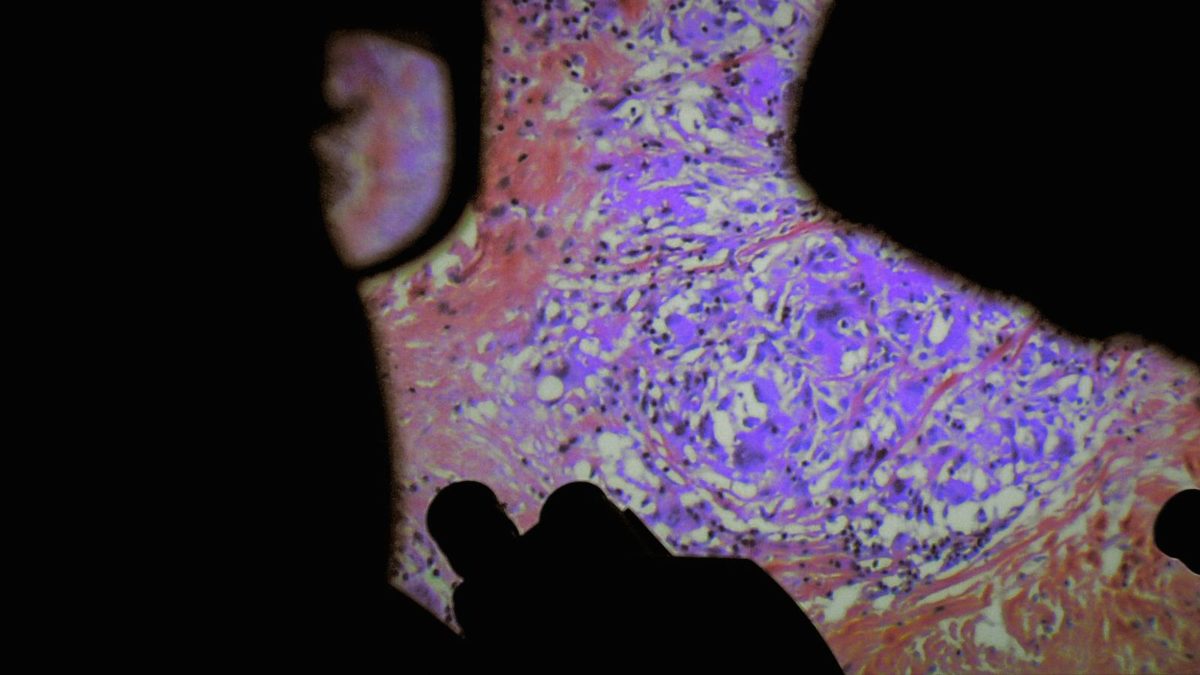

1. De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Verena Paravel & Lucien Castaing-Taylor)

A surgeon has a pleasant conversation with his patient. The camera pans up and we see the surgeon drilling screws into the man’s skull. Instruments are cutting and cleaning some internal organ. We then see it’s a man’s penis, which squirts out blood. If you’re not used to Verena Pavarel and Lucian Castaing-Taylor’s uniquely visceral style of documentary, this would be a bold first watch. De Humani Corporis Fabrica continues the duo’s masterful partnership in putting cameras where no one else has, yielding imagery no else has found, and turning it into a symphony of the human experience.