Some context might help. Between 1988 and 1997 the Baltimore-based filmmaker Rob Tregenza directed three features that amassed a small, enviable group of admirers. If it’s one thing to secure bookings at arthouses and galleries, it’s quite another for your debut film to be anointed some groundbreaking moment in American movies by Jonathan Rosenbaum and Dave Kehr. It is simply beyond precedent to attract the interest of Jean-Luc Godard: the two met during distribution of 1996’s For Ever Mozart and amassed enough kinship for Godard to extend favors to Tregenza’s 1997 feature Inside/Out, the sole feature he produced without directing. (Godard has always been uncredited, about which more below.)

What almost anyone sees of Tregenza’s work are cinematographer duties for Alex Cox (Three Businessmen) and Béla Tarr (Werckmeister Harmonies). His own films, meanwhile, struggled to endure: in all my travels he only came to attention with Godard’s passing and word of that producing credit, and earlier this year I downloaded his four films from a private torrent network that, whatever its much-appreciated level of access, only hosted horrid-looking copies of the first three. (2016’s Gavagai, by benefit of recent release, proved the exception.)

It was manna from heaven that the Museum of Modern Art would host a retrospective of Tregenza’s films, which I immediately asked for restored copies of, received, and watched in delighted short order. If not with lingering question about their obscurity: 1988’s Talking to Strangers is a “long-take” film boosted by its mordant sense of humor; 1991’s The Arc is a sharp vision of the American road with regional-cinema appeal; Inside/Out is rather obviously a formal astonishment; and Gavagai has the makings of arthouse staple. If I can’t speak to the choices, circumstances, or matters of taste that stopped these films dead, I can lament their long-held obscurity (and maybe begrudge in light of what American markets have prioritized).

I was given the opportunity to speak with Tregenza before his retrospective begins tomorrow, April 12, and in realizing this would be more or less the only extended interview with him available online––my sole reference was a single piece from 1998 that has probably avoided deletion by virtue of being in a newspaper’s archive––I was both starting at sea and using his generosity to get as much on-record as possible about an unsung American master.

Little did I know he did some background research before we met.

The Film Stage: It’s funny that you Googled me––that’s what I’m supposed to do. And when I tried with you I got just about nothing. I’ve never interviewed somebody who has fewer available interviews than you: all I could find online was a Baltimore Sun article from 25 years ago, and on my shelf I have Richard Brody’s Godard book, where I figured you were at least mentioned, so I pulled it off the shelf and found a three-page section. Otherwise nil. So where do I even begin? Maybe with the fact that Talking to Strangers was a year before sex, lies, and videotape, which is that era’s watershed independent American movie.

Rob Tregenza: That was also, strangely, the Sundance phenomenon––right before Geoffrey Gilmore got there. But it was still coming out of the beginning of that. So that’s where, sort of, the corporation––or incorporation––of independence as a brand… Sundance sort of did that. I didn’t make that transition. Talking to Strangers, I think, was offered to the predecessor, and they turned down. Then New Directors/New Films turned it down. The San Francisco Film Festival turned it down. So out of a wild lark we said, “Aim for the top! Berlin!” After all the misfortune of trying––not really fitting as “an American independent,” and certainly not fitting the business model or the brand––we ended up in Europe.

In terms of the historical consciousness of our work and where we’ve gone, we’ve always had more of a European entrée than a North American. That’s a part of it. There were not a lot of people running around wanting to interview me about anything. [Laughs] It’s part of the movement into the industrialization––or shall we say commercialization––of independent cinema. We missed the boat. Part of it was by choice; in part it was by fate. That’s one of the paradoxes of life.

Where did your filmmaking background emerge, and how did it turn to features?

My background started off just being a cinephile. I saw movies. In 1968 I saw La Jetée. I was a senior in high school. 16mm print. My mother rented the film. A 16mm projector we put in our living room, and looked at it, and it was that imprinting thing. At that point I was in still photography. What I wanted to do, I thought, is shoot stills. And all of a sudden there’s this thing called motion, right? And that iconic still where she looks up. It’s like [puts hand to chest] an epiphany, photogenie––all of a sudden it’s all there. I would say that’s the first one that hit me, and that’s in ’68. And then: poor college student freshman year, no car, no money, no date, wandering through a rainy night. “Free Movies!” on this sign stuck up.

So I go in, I sit down. It’s all these funny-looking people––to my mind they were funny-looking people. Berets. You can smoke in the theater at that point. Everyone’s smoking. I look up: there’s a low-hanging cloud over the screen. I sat back and they put it up on the screen––it was Through a Glass Darkly. I went, “Hmm! This is a world I know nothing about. This is a world I had no conception of.” So of course, being a sort of pseudo-intellectual, I went and read everything I could read about Bergman in one week. So then the next week I’m doing the same thing Friday night––no date, no money, no car––walking through the campus. “Free Movie.” Same funny people there: the berets, the cigarettes. It comes up––L’avventura. It was like… [Laughs] “This is a world I’d never known!” So I stumble back out into the night. And the next film that hit me real hard was Night and Fog, and that was in 1970. Those were the first imprinting films. So I really don’t think, Nick, I’ve honestly escaped them. And I’m not sure I want to.

You see those films. You leave college. What’s the period from there to Talking to Strangers, in a filmmaking practice?

I became a technician. I basically did anything I could to put my hands on technology. I had learned enough that if I could get my hands on the tools, they would teach me. But I had to get my hands on professional tools. I had learned enough in college that there’s a huge difference between a 16mm camera and a 35; and I learned there’s a huge difference between a Super 8 wind-up editing system and a Moviola. So I think what I got out of the early, technical part of my film education was that we were kind of denied the means of production in the process of being in a cheap film school––which is what my family could afford––so I said, “Okay, now I have to get around the technology.” So I took jobs, and at that point this was ‘69, ‘70. If I could work for somebody who was an assistant editor I’d go and do it––just to touch 35mm. If I could work as a first AC I would do it.

So I made no distinction. If I could get a job as a grip I’d take it. So that continued until about 1976, when I got into UCLA––Ph.D. program in cinema. I got into that because I’d been teaching at colleges and state schools, and accumulated a little bit of a reel and some academic standing. Then things changed: I’m not just trying to acquire the means of production. I’m now looking back through theater, philosophy, radical changes. And I was so fortunate I had two teachers who made a big difference to me: Raymond Durgnat, who was an English critic, and Brian Henderson. Those are the two most impressive intellectual forces––pre-Godard, because at that point I knew nothing about Godard. I mean, vaguely I knew Breathless, but nothing about Godard. So I took a left-hand turn away from technology into theory, history, and criticism. Henderson taught me to be suspicious of semiology. At that point that was the whole driving force and there was this attempt to take film theory in California down the French road. For me, I felt enlisted. So Durgnat helped that and Brian Henderson really assisted that. He showed us Weekend. I’m sitting in a supposed Ph.D. seminar and they go “Okay, now watch this.”

Then he went on about his two different systems of film theory, the radical use of the long take––that’s where that started––but the other thing that was important was that he asked us to read Godard on Godard. That was, I think, the most important intellectual part. Durgnat, important; Henderson, important; but Godard on Godard, most important. So that was all around ‘76, ‘77. That hooked me that way. So then I got married and all of a sudden you have to pay for diapers. [Laughs] All of a sudden you wonder, “How do we survive?” And that’s when I got into commercial filmmaking. Largely, at that point, I was shooting as a DP and operator: corporate films, 16mm so-called “documentaries,” and did pretty well.

Then we made a decision: my wife said, “Are you happy doing what you’re doing,” and I said, “No.” She asked, “What do you want to do?” I said, “I want to make features.” She said, “Why aren’t you doing it?” I said, “Well, we don’t have the money––obviously.” She said, “How do you get there?” I said, “I have to shoot 35. I can’t shoot 16. I’ve got to get out of 16.” So that was around ‘85. So from that point it was like: anything on 35mm I will shoot. I need my hands on the technology. From ‘85 to ‘87 was the “commercial period,” but what that was all about was––again––technology. But it was stepping from 16 to 35. Once I hit that, Talking to Strangers was a strange combination of Godard and his theories of reality, and also his theories of “the definitive by chance.” That’s the main concept I took out of Godard on Godard––which is what he used in Vivre Sa Vie. That’s why I did the long takes, no cuts. I didn’t start off with Godard; he found me, more or less, in the ‘80s.

Talking to Strangers doesn’t look easy to do, but if you know how to do it, it’s maybe a perfect concept for a first film: you can gather your movie in a kind of landspeed record, this literal 1:1 shooting ratio. So there’s theory, but does necessity become part of the equation?

Always. Always necessity. But what people don’t really understand––and I think part of it is just not understanding the means of production––is that a lot of it was shot with cranes. 27-foot cranes with remote cameras on the end. This, even in that period of time, was cost-prohibitive. It’s true: the scene in the bus is handheld. You put a camera on a wheelchair for eight minutes, just muscling through, but a lot of it is also a decision that the poetics of the structure force you into. You say, “Okay, I’m going to make a standard plan-séquence. How do I do it?” The thought comes, like the confession [scene], “How do you get all the way up, do it from one side of the booth to the other? How do you follow that through?”

So if you’re following the limitations of technology––the poetics of it––you’ve got to come up with “Okay, I need a crane.” Not just any crane––a 27-foot camera system, a Tulip Crane with the extension on. A remote control. A video assist. And all of a sudden your budget’s shot. Compared to the idea “let’s grab a camera,” like the scene in the bus––relatively cheap. So a lot of people think it’s just easy to pick up a camera and do a 10-minute take, but behind it is the poetics of it: once you adopt the structure of the poem, you live and die within it. Blessings come––if you are patient. You need the rhyme scheme, the confinement, of the structure.

Talking to Strangers

That film came out in 1988, a time I wasn’t alive for but always hear––and see evidence––of as a heavily consumerist, close-minded period, and this film clearly exists so far outside what, from that era, endures in the present. Was working in commercial environments an influence for a kind of pushing-away?

Yeah. I think, Nick, that’s part of it, but the other thing that goes back into it is that I did my dissertation on Martin Heidegger. Most of it’s written on Being in Time, but there’s also later Heidegerrean stuff, so I was fully conscious of his critique of technology, of consumerism––also some of the negative things we know were part of Heidegger. I think that was part of recognizing the beast in the system and saying, “Okay, there can be a turn. There can be an opportunity within the art. The danger is there, but in the danger there’s possibility to turn it.” So I think I was trying to say, “How do we turn it, yet at the same level do it at the same level as the discourse?” Because I think it’s very easy to rail against the machine, the system, and if you’re doing it at a lower level of communication or praxis that can be demeaned or trivialized––“Oh, it’s not a film”––they undercut the content, the politics, the ethics, and you’re marginalized because you’re not at a level of discourse.

So that was part of what I was doing in wanting to go back to 35: you look at our films and they’re in-focus, sharp, up at the level of discourse that was part of traditional standards, but the content––as in: the ethics––are completely different. I’m turning; I’m trying to find a way to use the art against the idea of what inflames or constrains thinking, the ability to be free, the poetics of art. I always thought: “I have to hit that level to not be marginalized, to not be trivialized, and if I can make that even approximately…” I can’t spend millions of dollars on a movie, but it’s in focus, it’s sharp, it’s in Dolby Stereo.

Do you still feel connected to the ideas in the films? Do they remind you of a younger self––what you then felt and believed in––or are you still connected to them?

Another good question! I don’t know. I haven’t thought about that. I believe there’s something called historical consciousness. Right? It goes through time and art. I don’t believe I am an artist in the sense of an auteur. I believe I’m the passageway, and that through the passageway I, in my existence, comes the art. That doesn’t mean I don’t have the ability to shape it, in some sense, but to some extent I don’t believe intentionality matters. I believe I am the passageway the art goes through. I think there’s going to be a relationship between a unity of opposites, in some cases, where diametric oppositions are not what we’re looking for. We’re looking for the unity of our position within the process of change. That is part of historical consciousness this is going through, and I am just the passageway with some degree of control.

But not an auteur. Because when I pick up the camera I pick up the tool. I didn’t create the tool; I didn’t create the lens; I didn’t create the aspect ratio. When I start editing––fortunately or unfortunately, I didn’t have a system; I’m still on an upright Moviola as far as my head goes––basically it’s an ongoing dialogue, part of the conversation. I’m going to make a decision; I’m going to make a choice. That could be like Derrida said, “There’s a signature in the art.” I think Roland Barthes and Derrida wrote about that: the intentionality of the filmmaker is not the causal explanation of the understanding. Nevertheless I think I’ve participated in it, but I’m using tools and language I didn’t create.

That’s remarkably humble. Looking at the credits for your films is like a one-man show: written, directed, produced, edited by Rob Tregenza.

[Laughs] It’s a little embarrassing.

You think so?

Yeah. Honestly, the reason, Nick, it’s that way is because I didn’t have any money, so I had to do it myself. It’s not an attempt to claim authorship. I mean, yes: I did the director function. But I couldn’t hire an editor, a camera operator, a DP; I couldn’t hire a screenwriter, a producer. So all those functions roll into my job description. I don’t think it increases my “ownership” of the intentionality of the art. In fact, it makes it go the other way.

There’s three years between Talking to Strangers and The Arc. Where was your head at, after a debut feature, about wanting to continue filmmaking practice? It wouldn’t take much to determine they were made by the same person, but The Arc starts on a shocking note––this music-laden montage so far removed from Talking to Strangers that I almost checked the link to make sure I was watching the right movie.

[Laughs] That was desired. Back to Godard: one of the things Godard had in Godard on Godard was this rejection of Bazin’s idea of the plan-séquence––the long take––being inherently more “real.” Godard has an article called “Montage, My Fine Care.” That was a key part of my development. So I didn’t want to get caught in the trap of plan-séquence. I thought, “How can I prove that?” We can always do that, did it––one shot, one time, virtually a shooting ratio of 1:1. But Godard says you can’t have the long take without the cut. That takes an opposition to Bazin’s idea of realism, which I think is at the core of a lot of misunderstandings about cinema. He says “No, no, we still have a cut. The cut’s going to occur. Whether it’s ten minutes––because 1,000 foot of film is the duration of a long shot on 35––or whether it’s five seconds with Eisenstein, there’s a cut, and a cut is where montage occurs.” He also says whenever there’s a point-of-view shot the cut occurs.

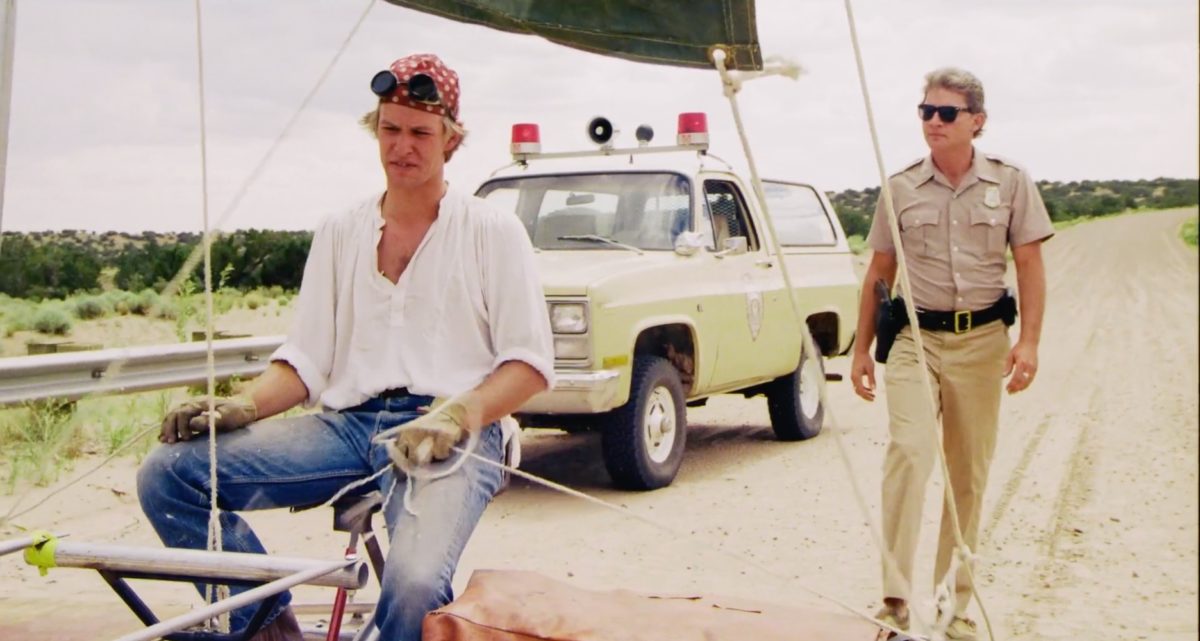

So I was determined not to make the same film twice. I was determined to say “Okay, I’ve got a limited number of films.” And I knew that. So I’m not going to do the same film. I could’ve done Talking to Strangers for ten films straight and that would’ve proved nothing. In fact––I won’t say who she was––when I showed The Arc to some distribution people back before it went to Berlin, I’m standing out in the lobby waiting for them to come out. She walks out after 10 minutes and is surprised to see me standing there. She said, “Ugh. Well, basically, you sold out.” And I said, “How do you know that? You’ve just seen the first 10 minutes.” She said, “It’s commercial! It’s so commercial! It’s so many edits.” And I said “Well, maybe I was doing something different. Maybe you should go back in.” She didn’t want to go back. Then she sort of turned, in this big fur coat, on her heel and looked back and said “You know, with the money you wasted on that film you could’ve fed a village of Indigenous Indians in Guatemala for a year.”

Now: I was shocked. I’m saying in my mind, “She’s a distribution maven. Maybe she’s going to distribute my film.” But that was a huge reaction to The Arc: “Why, if you do the ultimate plan-séquence, are you doing montage?” Because I don’t think the long take is inherently any more realistic than the cut. And I think it’s the juxtaposition––the opposition––between them, the unity of opposites, which is essential to take cinema further. Just fixating on one style, one performance element––as people want me to do––is probably a recipe for the end of the art. The Arc was in Berlin. Did well. Opening night in Berlin. People forget that, don’t know that. Once again New Directors/New Films said no. Sundance said no. All the so-called “independent” people passed on it. I think it played in Chicago at the film festival and Toronto. Thank heavens that was a co-production with Film Four International, who did pre-sales on it. So it played everywhere around the world and on TV; never in the U.S.

The Arc

There’s kind of… not that justice has to enter the equation, but at least something poetic in having this retro at MoMA, the home of New Directors/New Films.

One week, Nick, after New Directors. Isn’t that strange?

Vindicated by time.

Did you read Vincent Canby’s review of Talking to Strangers?

I found it.

He has this little barb. Of course he had to be the great man; he had to be “witty.” Richard Peña booked that as part of the opening of the Walter Reade. He said, “It’s part of a Great Films/Great Filmmaker thing playing down at the Walter Reade. Maybe that’s putting too much weight on this filmmaker. We’ll have to wait and see.” Damning with faint praise. [Laughs] The connoisseur film critics of that day had to always keep their powder dry––praise and take back. There was a negotiation with young filmmakers: they didn’t want to go crazy, out on the edge, and at the same time maintain their objectivity.

I’m very curious about your working relationship with Jean-Luc Godard. Information is vague. Jonathan Rosenbaum published some letters exchanged around the time of Inside/Out.

Right.

And Inside/Out is often seen as significant for being the one feature Godard produced without directing. But the three or four pages about you in Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema suggest he didn’t have that strong a producing hand, or perhaps curtailed involvement after growing uncomfortable over… something. Again: vague. Really, I’d just like to know straight from the source what that was all about.

To get into that we have to go back to distribution. Which people don’t understand but you understand, having been in the middle of it. Talking to Strangers, basically, did well. I got phone calls from people saying, “We’d like to show it.” The majority of those people were art galleries. The Chicago Film Center. Boston. Eventually, New York with Peña. They were calling us based on Jonathan’s review and Dave Kehr’s review––we were just sitting there, getting phone calls. That was fine. Building a rolodex of contacts. So then we go off and do The Arc. We had two distributors we talked to for Talking to Strangers; one wanted to reduce it to 16mm and put it out on a 16mm print. I said, “Excuse me: it’s shot on 35mm with a stereo mix. Why would we put it out on 16mm?” “Well, it’s the best market to distribute it…” It was the economics of it. They didn’t have the visionary thing to go, “Maybe if we put this out on 35mm we wouldn’t have to change this.” But basically that was their level. No distribution? We self-distribute it.

Arc comes along; Channel Four International picks it up. They get the sole world-sales rights and we kept North America. We think, “Maybe somebody’s going to come back.” Nothing. We’re sitting there going, “Hmm. We’ve got these distribution contacts from Talking. Maybe we should go into distribution.” So we created a thing called Cinema Parallel. Not competition, not setting ourselves as the antithesis of Hollywood; strictly a parallel. So I talked to Piers Handling. I said, “What are the films that you feel have been overlooked that really should be distributed in North America?” This was, I think, 1992. He said Diably, diably by Dorota Kędzierzawska––Polish woman, fantastic film. And Seventh Continent. So we said, “Okay.” My wife and I acquired them in 1992––that was right at the point Europeans were desperate to get any product to North America. We sent signed contracts for a term of 12 years. So we had Devils Devils by Kędzierzawska Seventh Continent. We picked up the phone and called all the people we talked to for Talking to Strangers. Some were willing to book it; some weren’t. The usual suspects did. Trying to get Seventh Continent booked anywhere in North America [Laughs] in ‘92––I mean, they ran from that movie.

So then we went back to Toronto in ‘93 and are looking at Hélas pour moi, which I fell in love with. I said, “We’ve got these two. Let’s see what they want for it.” They couldn’t quite blow me away because I had two films, so for a ridiculous––which I cannot disclose––amount of money, ridiculous meaning “small,” I got the rights for Hélas pour moi. I knew nothing about it other than that I loved it. I didn’t know the problems with Godard and Depardieu; I didn’t know about all the backbiting. I just said, “I like this film.” So from 1993 until 1996 we distributed it in North America; every place we could book it we booked it. And it was hard. People did not care about Godard in ‘93. Thankfully, Amy Taubin saw it and gave it a good review––you could eke out bookings off that. So every time it plays I’m sending Godard the box office and I’m sending him the reviews. He doesn’t respond. Nothing comes back. It’s like putting the bottle in the ocean. But two years, three years we do that. So back to Museum of Modern Art: somehow they’re involved with JLG/JLG. We go up to New York; after the screening we nod at Jean-Luc, Jean-Luc nods at us, Larry Kardish says “This is Rob Tregenza from Cinema Parallel.” [Mimes smoking, nods] He has his cigar; very polite. No conversation. Then I get a phone call in late ‘95, ‘96––he’d done For Ever Mozart and wanted us to distribute that in North America.

First time I talked to him was on the phone: I was doing a retrospective for Béla Tarr. In the meantime I’d picked up Sátántangó, another undistributed film, and Damnation and Up, Down, Fragile, a good film by Rivette. So I’m talking to Godard, who said––to make a long story short––”Come to Paris and we’ll show the film.” So it took a distribution company to get into the confidence, I think, of Jean-Luc. And what happened in ‘96: I told him, “I’m tapped out. There’s no way I can distribute the film.” He said, “Will you be the sales agent?” I said, “Yes.” At that point he was trying to get into NYFF; I’m sort of his agent, dealing with Peña and trying to work that, and Piers Handling in Toronto was much more receptive than New York was. I said to Jean-Luc, “Let’s go to Toronto.” He said okay under a couple conditions and he ended up in Toronto. They asked him to pick a film for the director’s spotlight; lo and behold he picked Talking to Strangers. He had only ever seen a VHS copy; never saw it projected until Toronto. So that is the long, meandering answer to your question. Without Cinema Parallel I would’ve never had a relationship with Béla Tarr, Jean-Luc, Rivette––all of that.

So to what extent did he help Inside/Out’s production? Giving input? And was there a point he recused himself?

Yes. I think there was a lot of interesting things happening in that period of time. One was the fact that he was initially interested in acting in the film––he was going to play the part played by the French actor, Frédéric Pierrot, and then decided not to. Part of that, I think––and I sort of intimated this to Brody, and Brody sort of picked up on some of it––Jean-Luc wanted to use Bérangère Allaux in the film that he was planning on making, that was part of his vision of going from For Ever Mozart to this film. And the film was never made because it would require incredible amounts of special effects, and it was prohibitive. He was talking to Tom Luddy and other people on the west coast about how to make it, this story about a woman who turns into a pig––physically a pig. That’s bubbling in the background, too, this other project. And this desire to work with Bérangère Allaux again after For Ever Mozart.

I didn’t know––I was not close enough––to know what was going on there, but I could hear and know to cast Bérangère for Inside/Out, but Jean-Luc was also interested in doing this other film. I think it was part of this continuity: yes, he wanted to help Cinema Parallel; yes, he did; but he’s also biding time to see if he could get this other film off the ground. It didn’t and I don’t know why. Gill Holland, my American producer on the film, has a set of opinions you can talk to him about. But all of a sudden it came down to: Jean-Luc doesn’t want to be in the film but he wants to produce it, so that’s how we picked up Frédéric Pierrot. And there was this sort of thaw. But he was still involved; I mixed it in the studio in Rolle. And he was the most cooperative producer I’ve ever worked with. [Laughs] I mean, absolutely a dream. He’d come in every day after the mix––just sit there and smoke––then we’d go out, have dinner, drink. At the end of the next day he’d come in and smoke, make a comment. Absolutely no, “Do this. Do that.” No.

He had one comment like… there’s a scene where it tilts towards the light in the sanitarium––it’s hard to see; it’s black-and-white––Jean-Luc says, “They didn’t have fluorescent tubes back then.” That was the only negative comment. Otherwise he sat there and enjoyed it and we went out to dinner. It came to Cannes. At that point he decided he didn’t want to be a co-producer and be inconvenienced, so we sort of just stopped that whole PR train as part of the abruptness of it. If he did not want to be listed as the co-producer, which he was, then how do you handle that PR nightmare? So we shut it down. When people asked about it we just, not to be purposely evasive, didn’t deal with it.

Inside/Out

That’s sort of what I gathered, but in Brody’s book it ends abruptly. I didn’t know if there was bad blood.

There wasn’t. Basically he called me up later to shoot a film for him, and unfortunately I was working on my boat. I had a sailboat I lived on and off for 13 years up and down the east coast. I’m working on the boat, and by the time I’m back in Maryland, to my answering machine––much to my chagrin and pain––I didn’t answer him back in time. Brody mentions that. There’s a scene in JLG/JLG where Jean-Luc’s sitting in a room with multiple television sets and he’s got a remote control and he’s sort of going around, changing channels. That’s the feeling I had with him: that while you’re the channel he wants to be on, you’re on, and when he’s doing something else, he’s doing something else.

You have to understand it’s not a reflection on your relationship with him when he changes the channel. It doesn’t change the affection or professionalism. It’s just, “Boom. I’m somewhere else.” That was part of realizing things had changed. With Godard, everything changes. He was one of the kindest people I’ve ever met but one of the most mercurial. He was his films. Brody got that right. All those changes, that shifting.

Did you maintain contact in the 25 years between Inside/Out and his passing?

No. Other than when he called me to do that film. I think that’s part of why I was distraught when he died: I kept thinking, “Maybe he’ll change the channel. Maybe he’ll come back around.” The finality of that; the finitude of that. It was great for us to later be quoted in Histoire(s) du cinéma: he has this long shot from Talking to Strangers in the end of one of the sections of the woman on the water taxi at the end of Seul le cinéma––Only Cinema. So I look back and think, “He didn’t have to put that in 20 years later.” It’s some vindication. He was, from my experience, interestingly remote, yet could switch a button and be tremendously conscious and present.

He wanted me to go to Paris to see Mozart. I said, “Jean-Luc, I don’t think I can do it. We don’t have the money.” So he said, “I want you to come. Come.” My wife looked up the cheapest fares from New York to Paris. We found one and are in the process of buying the ticket. He calls back and says, “Go to Dulles. There’s a ticket waiting for you at Dulles.” So I go to Dulles: business-class ticket on Air France. I had never been business class on Air France; I mean, I hadn’t been first-class on many flights anywhere. So I’m sitting there. “Wow, this is wild.” Drink too much champagne on the way over. I get to the airport and take a bus to the hotel. Fall into bed. And then I wake up in the morning––I have to go to Gaumont to look at For Ever Mozart. I wake up, turn the TV set on, and I’m looking at water and suitcases floating on the water, and I’m going, “This is weird.” It says, “Flight 800.” And I almost fall off the bed because the flight we were going to book––before Godard gave us the ticket––was flight 800.

Oh my God.

So then I go to Gaumont. He’s sitting there, smoking, and I said “You know, Jean-Luc, if you hadn’t sent me that ticket I’d be dead.” And he just smokes, looks up––this typical Godard look––to the ceiling. No facial expression. No great change. Just, “Oh.” And we go about talking about the film. But that’s the sort of substantiation he had: he could be totally there and he could be remote, and he could be totally aware of what the “there” is when he’s not there. That, to me, was the interesting thing. So Piers Handling was there after the screening: he came to a café, and Piers is inviting him to Toronto, and I have this suspicion New York doesn’t want it.

I said––the only time I ever asked him about this––“What was it like doing Hélas pour moi with Depardieu?” He always had nice sports jackets. He stood up, took his sport jacket off, turned it inside-out, put it back on, and sat back at the table and kept smoking. That was his response. So at that point… I had lawyer problems because the original name for Inside/Out was Springfield, and we were going to shoot at Springfield Hospital and they wouldn’t let us use the name because it was some violation. So I just said, “Okay. Fine. We’ll call the film Inside/Out.” So it was an interesting situation. Very, very important, obviously, in my life. We would not have made Inside/Out without him.

What accounted for the nearly 20-year gap from Inside/Out and Gavagai?

Well, it’s really hard, Nick, when you’re not a “young” filmmaker. You ride the wave of being, in a sense, the next big thing––potentially the next big thing––so you make three films and you’re not the big thing. They don’t get distribution; they may be well-received. So you have to sort of retreat and say “Okay, I’m still a filmmaker, but how do I pay the bills? How do I regroup?” Basically that’s what happened: I said, “I’m going to find a way to survive because I don’t want to try to make meaningless stuff.” So basically it took that long for the wheel to come around, and when it did I was fortunate enough to be able to say “Okay, the wheel’s coming around. Let’s grab it and do it.”

When you’re not a “young” filmmaker anymore and don’t have the upside of being able to hook your wagon to the next XYZ, you have to wait your turn. So basically what I did was spend a lot of time thinking about cinema, and that’s led to my new book that’s out now––which is called Tregenza Mise-En-Scène. It’s being published in Poland by the Polish National Film School in Łódź; it’s coming out this month and it’s all my theoretical work of the last 10, 15 years. You don’t make the films, so you think about them.

Is your book also in English?

No. I find that ironic and interesting.

Gavagai

Does Gavagai have pent-up energy driving it?

Yeah. Yeah, it does. And the one I’m writing now, I’m hopefully going to do this year, is even more so. I’m not comparing myself to Tarkovsky at all––two different kinds of filmmakers, two different kinds of films––but he only made seven films. You have somebody who was massively––I think we all agree––talented. Seven feature films; with Steamroller, seven-and–a-half. That amazes me, someone who had that quality. Again, because of the economic systems, the politics, whatever… I would’ve loved to see what he would’ve done with 20 films. But maybe they would’ve not been as good. You read Sculpting in Time and see––as you were alluding to––this pent-up denial of praxis which leads to philosophy and to aesthetics and to theology, which is quite amazing.

What is this new film?

I want to go back to Norway and shoot the next film in Norway. It’s set in Norway in 1945, a small industrial town right at the cusp when the Germans are pulling out and the resistance is taking over. A woman is put into this position, as a spy, to spy on the locals for the Germans. Right in the middle of it she’s caught between the Germans and the nationals. How does she function? It’s kind of a place where we are today, in our society: we’re right at the cusp between two different cultures. We’re in the middle of it and are perceived, somehow, as being part of it or betraying it. What happens morally, ethically when you’re sort of put in a position where you have to become a spy in a culture that’s rapidly changing? Can you maintain some sort of ethical position, or is that all relative? I want to do it and shoot it in November, December of this year. Under $300,000, 35mm. We are still in the process of finding investors.

Are there hopes for these restorations and this retrospective? Is it just that they can be restored and seen? Or is there something deeper?

That’s a large amount of it: they have been restored. Right now, three of those four prints are brand-new 35mm prints. But the irony is that they’re going to go into storage somewhere. And the probability, outside of this week, that those prints are going to be projected again are… unless it’s another situation that requires somebody taking the chance. Just to make a 35 print now of a black-and-white film is around $17,000. Just to make a print. The economics come back in. Am I going to give the new Inside/Out print to a local school or cinematheque? It’s just cost-prohibitive. So what will happen then is the 4K masters will go out. As much as I prefer the analog experience, the financial reality is that there is this sea change in distribution. I like the analog image.

I also like the historical fact that when you walk in a room and see a pristine 35mm print, in a magical way you are back in time. Godard talks about that in Histoire(s) du cinéma––that’s part of the historicity of cinema, its capacity as a mechanical, chemical medium to time-travel. And I don’t get that feeling, Nick, when I look at a 4K digital projection of the same film. This is part of the photogenie, to go to [Jean] Epstein. Does it have to be mechanical? Does it have to be chemical? [Walter] Benjamin’s thing: is the aura of art lost when it goes digital? I don’t have the answer to that. Your generation’s going to figure that out. The cinematic event requires widescreen projection, now-digital audio, and human beings in anonymous proximity. When that changes, the event––as a cinematic event––changes. There’s no denying that. The question becomes what’s lost or gained to the art in the process.

“Rob Tregenza: Thinking with Cinema” runs at the Museum of Modern Art from April 12 to 16.