The last decade has seen dozens of cinematic stories directly and indirectly affected by the 2007-08 financial crisis, but with the exception of Inside Job, none of them have as much gushing, guttural anger about the housing crisis as Adam McKay’s The Big Short.

The Big Short is keen early and often on demonizing the excesses of capitalism. Accompanied by Shaft-style funk flourishes, the film begins with a montage of nebbish market men beginning their descent into morally dubious traders. This is a film that’s not only on the right side of history, but deeply proud and angry about it.

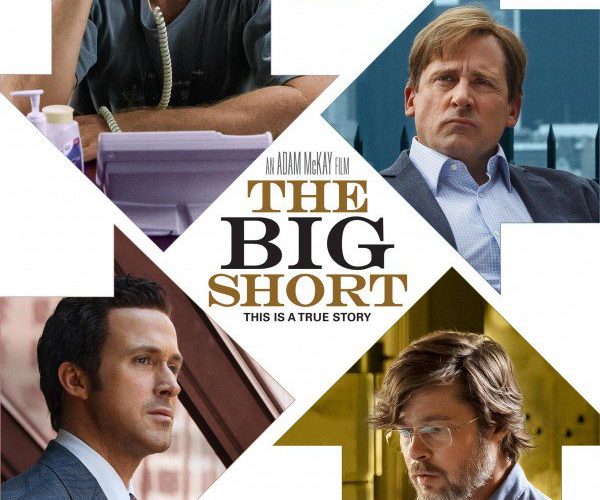

There’s easily a dozen characters in the periphery, but The Big Short brings together six seemingly unconnected players who all cash in off the implosion of the financial market. There’s Michael Burry (Christian Bale), a half-blind, neurotic loner who would be both disgusted and right at home with Bale’s own Patrick Bateman. He’s bad with people, deploying a deadpan honesty, sunken delivery and a clear misunderstanding of proper human etiquette. But he’s also an absolute wiz with numbers, and manages his own massive West Coast-based hedge fund, Scion Capital. Bale brings an animalistic single-mindedness as he sacrifices sleep, work and his sanity on a gamble that seems astronomically implausible to his employers.

Mark Baum (Steve Carell), another hedge fund manager, is the moral center. He’s an obnoxious loudmouth who’s slowly oozed into a depression after seeing decades of mistreatment of the average person by Wall Street. He’s a crusader for the common man, and also more explicitly, a mouthpiece for the script’s abject frustration with the system. There’s at least a dozen of his lines that are nothing more than stylized exposition. Even as Carell extends more and more skin into the trade, he wants so badly to be wrong about how mucked up the system has become.

Elsewhere, there’s Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling), a venal bottom feeder who comes across Burry’s projections for a teetering economy, and immediately schemes how to make the highest amount of cash off this revelation. Vennett’s character works as a protagonist though because as Baum states after he meets him, “He’s so transparent in his self-interest I kind of trust him.” He’s a very punchable windbag, but he delivers his noxious insights with such blistering confidence that he almost becomes infectious.

Finally, the remaining three can be grouped together although only two of them truly work in tandem. Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Whitrock), are two small pond garage traders who become involved in the most cinematically un-engaging way possible: by finding Burry’s report on the table (or, maybe not, thanks to the sly narration). By virtue of both their small stature and their lesser involvement, they’re less individually compelling than the other leads. They’re mostly just anxious all the time about the outcome of their trades. Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt at his maximum drowsiness) is their in, a resentful former trader who’s abandoned the market for less ethically malleable work after decades of unhappiness.

The Big Short makes no qualms about its political leanings. It’s mad as hell, and it’s not going to take it anymore. Moreover, it’s not afraid to be overwhelmingly smug and self-congratulatory. After all, we’re in the aftermath of a financial crisis that almost universally disgusts the American public. This is the time to kick them when they’re down.

It presents itself as aggressive and mean, but it’s so nobly committed to the truth and honesty that it might as well be an Oliver Stone film. That brazen self-confidence is potentially going to bother many people, but this is the rare film that actually wields that glibness in a way that doesn’t feel forced.

For better or for worse, the people involved in this crisis are slimy. And while maybe business school dropouts who shimmied their way into real estate positions only to place all bets on the system not failing, don’t deserve to be diminished to caricatures (i.e. Max Greenfield’s hilariously clueless real estate opportunist), it’s certainly immensely satisfying.

McKay’s even braver in how transparently he dumbs down the overall material. Not only does he ask caustic rhetorical questions of the audience like “does it make you feel bored or stupid” moments after prefacing the spark notes of the financial crisis, he also continually relies on celebrity-led tangents that explain key jargon like CDOs, bespoke tranche opportunity, etc. And it mostly works.

There is a certain breaking point where some of the explanation starts to feel as redundant as seeing a “previously on” segment moments after binging ten episodes of a show. But when it comes time to fly through the labyrinthian discussions about CDOs and the methods of playing the market, it’s startling coherent in a way that even something expressly academic like Inside Job couldn’t accomplish.

It’s not altogether that surprising that McKay chose this project. His incensed worldview of Wall Street and the banks has been on full display since The Other Guys, which notoriously featured a powerpoint call-out of Wall Street’s worst offenses. But he really throws his all into this film, pulling out every stop, from manipulative insert shots of families piling into a car with all of their worldly possessions (their landlord filled out the loan contract with their dogs name) to adding in laugh tracks in scenes of particularly egregious behavior. And that’s not even delving into the interspersed slideshow stills, fourth wall breaking didactics, and talking head sight gags.

McKay’s comedic background proves invaluable here in bringing a real thump to the dialogue. He understands how vocal dynamics can make a scene comedic and knows when to lean into comedy and when to keep things sober. But even with his cynical viewpoint, McKay steps in when things get out of hand as well. In one scene with Vennett, the character hurls racial slurs at an assistant, only for that actor to turn toward the screen and correct every one of his generalizations.

He’s equally adept at more subtle observations though. An earlier scene has Baum angrily monologuing about corporations screwing over the American public as he walks past CVS, one of the worst-rated employers in the country. He’s not above a sight gag, even with a story that’s this tragic.

The filmmaking here is everything but the kitchen sink with Paul Greengrass’ regular cinematographer Barry Ackroyd bringing a controlled chaos to the shot choice. The camera is as much an active participant in the carnage as it observes and reacts to each mounting absurdity about the impending crash. It even reaches a point where the frame flickers during an extreme close-up, as if it’s blinking in full realization of what’s being said.

The Big Short does well by most of its main players, but there is a wish that it would give any of the female characters something to do. Marisa Tomei is relegated to the two worst scenes in the film as the buffer to Baum in the wake of a tragedy, while Karen Gillan is undermined on sight as a babbling ditz whose sole purpose is to illustrate the lack of conflict of interest within Wall Street. Melissa Leo is treated better, playing a representative of Standard & Poor’s, but this film almost entirely views women as eye candy or victims.

It is slightly frustrating as well to see all of the people involved on a lower level generalized as products of bro bravado, but it’s easier to paint them as the villain, even as it mistakes greed as the only motivation for why people do the wrong thing. There’s another far more ethically fluid film to be made about those subprime loan sellers that doesn’t simply make them feral greed hounds. This isn’t that film, but it’s nonetheless an immensely entertaining and worthwhile document of America’s modern horror story.

The Big Short is now in limited release and expands wide on December 23rd.