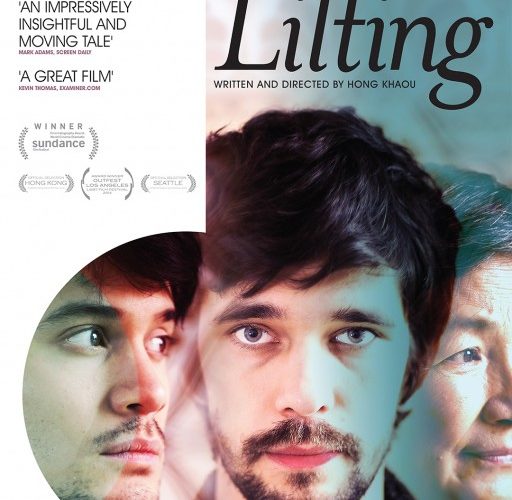

There’s no better title for Hong Khaou‘s feature debut than the one given: Lilting. It describes the pacing and aesthetic as guilt and grief intertwine with memory and reality fading together within a single camera pan for a joltingly emotive effect. It also illustrates each character’s cautious trepidation amidst tragedy and their desire to find acceptance in a powerfully calm rhythm. We’re ushered into the life of a Cambodian Chinese mother (Pei-pei Cheng‘s Junn) living in London with no one but a kindly British gentleman down the hall buying her flowers. They’re separated by language, but her words are translated for us to unearth a longing for family and the struggle against isolation harbored. Only when her recently deceased son’s lover Richard (Ben Whishaw)—whom she believed was simply his roommate—arrives does she learn she isn’t alone.

Far from an overnight discovery, though, his arrival causes more trouble than not initially due to a tumultuous relationship bred from Kai’s (Andrew Leung) inability to tell her the truth. Junn therefore saw Richard as the man who took her son’s spare room, forcing her to live in a retirement community. He needed the car and made Kai take the bus; he was why she’s locked out of sight and away from the love received when mother and son resided under the same roof. Conversely, her constant neediness was what Richard believed kept Kai on edge and uncomfortable in his own skin. Her overbearing nature drove a wedge between them until Kai felt he must explain it to her alone. And as a result, both Richard and Junn blamed the other for their love’s death.

Dealing with their language barrier, cultural preconceptions, and the want to fill an impossibly big hole seemingly growing larger, Lilting shows humanity, warts and all. We watch as Richard and Junn are constantly reminded of a time when Kai was theirs—the day before his death replaying and contextually changing as new details about their respective unions with him are exposed. There’s a lot of misplaced anger and assumed pity as the two balance the reason they face each other now and the knowledge of how different things might have been if they’d done so months before. They truly are the only other person in the world who’s able to understand what’s happening. He’s willing to take the time to hear her and no one loved Kai as much as he did except she.

So Richard’s introduction into her world with a translator in Vann (Naomi Christie) can be seen as nothing more than a way to enter and ensure she’s doing okay without Kai as he too has struggled mightily since his death. He brings the girl under the auspices that she could help Junn communicate with her new “boyfriend” Alan (Peter Bowles), the two as of yet merely walking around the grounds hearing only cadence and tone while indecipherable words are spoken. These sessions are sweetly adorable as nerves replace the confidence of ambiguity’s even footing—forcing them to learn about the other and deal with the pain such revelations bring. It’s almost as though Richard is preparing her, showing that life is messy and that we must deal with surprises and know love can trump all.

As tensions between Junn and Alan arise, however, Richard’s true motivations—albeit not pre-meditated—bubble to the surface. His resentment towards her comes out because he sees her doing exactly what he believed she’d do if Kai told the truth. Those assumptions were fueled by Kai’s trepidation, his cautious outlook making Richard think something about Junn that may not have been true. And with this resentment comes her anger in seeing his attitude reveal the person she thought he was. To her he’s come to try and make amends as though he’s acknowledging his fault in Kai’s death. Junn will not be pitied or manipulated, though, so she raises her defenses and holds tight to the “mother card” she doesn’t know can be matched by this man who is a mere stranger after all.

And this ebb and flow is excruciatingly beautiful and brutal to watch thanks to Whishaw’s portrayal of the still broken Richard. He’s a bundle of nerves doing his best to take Junn’s coldness in stride and toe the line of truth so as not to taint her view of Kai in case his homosexuality would. The moments where he cannot control his emotions are heartbreaking; his want to choke back tears involuntarily usurping the desire for a hug he can’t steal and risk making things worse. He is raw and exposed while Cheng’s Junn has adapted a stern stoicism, knowing she must grip her memories of Kai tight so as not to lose them in her old age. She guards herself from Richard’s actions unaware that he could actually bring her son closer to her than ever before.

Their anger, compassion, and longing are on full display thanks to Khaou’s decision let his story breathe. He allows their conversations to occur in their differing languages with arguments breaking out and empathy pushing in. Lines of dialogue conjure memories of Kai’s final day, both Richard and Junn’s love overlapping for us like it never can them. It’s a stunningly crafted series of events that works its way towards the characters’ inevitable collision of rage, blame, and emptiness. Khaou carefully constructs each scene for maximum impact from the first’s conversation between Junn and Kai to the last—intentional repetition expressing the experience’s ever-changing evolution. We may not know whether Richard and Junn will forgive themselves, but we know they never can until they relieve their pain and acknowledge the other’s claim to the man they loved.

Lilting opens at NYC’s Village East Cinemas on Friday, September 26th and LA’s Sundance Sunset Cinema and Laemmle’s Playhouse on October 3rd.