Whether it’s a matter of strong narrative direction and attractive aesthetic dressings bringing a film to life or, quite possibly, attractive aesthetic dressings doing a great deal to support lackadaisical narrative direction, Hungry Hearts scales its greatest heights when playing to the inconceivable and unsolvable. This is, after all, a film featuring a scene in which the protagonist, Jude (Adam Driver), presents a credible case to child services about the abuse his wife is inflicting upon their child, but is left essentially empty-handed for lacking direct evidence — except for when the social worker goes against protocol and suggests he kidnap the child to save its life.

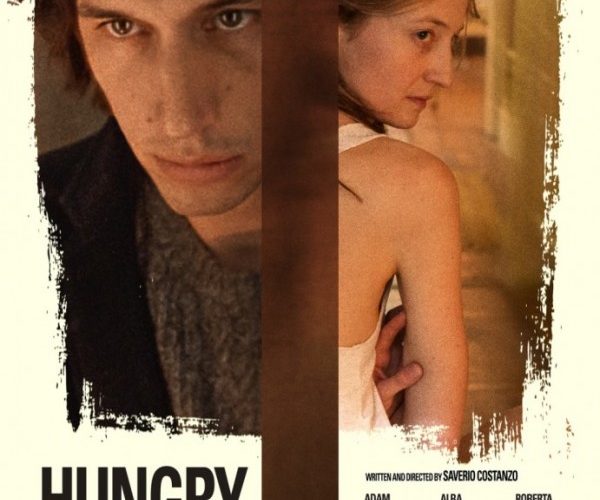

In most scenarios, this would be an eyebrow-conjoining, “what?”-inducing incident. In this particular instance, though, what we’re given is photographed with a strong eye for the paranoia and horror its central figure is enduring; the central figure is himself brought to life by a committed, consistently true-to-life performance; and, in its establishment of desperate stakes, is more or less (it can sometimes be hard to tell which) of a piece with the more effective passages — thanks to internal logic more than real-world logic, sure, but that’s not nothing. There’s much to credit in Saverio Costanzo’s adaptation of a Marco Franzoso novel, a film that’s earned attention almost exclusively due to the fact that its two leads, Driver and Alba Rohrwacher, made a rare one-film, two-person win of Venice’s Volpi Cup (the festival’s equivalent to Best Actor and Best Actress). For often being a single-location two-hander that is almost solely centered on their conflict — Mina, wife to Jude and mother of his child, refuses to feed the baby due to the belief that toxins in almost any food will stunt his growth — such an allocation of notice is understood.

But Costanzo and cinematographer Fabio Cianchetti are as interested in tone and state of mind as the work of the performers. Certainly not content to let words and verbalizations carry the picture entire, they paint a compelling portrait of New York — as dirty (the grain of 16mm cinematography leaves a significant imprint), massive (on-location street shooting is always done from a distance, shrinking main characters into figures within a sea of people), and yet, through its 1.66 aspect ratio and frequent alternation of lenses (fish-eye included), claustrophobic. Consider the opening sequence — in which Jude and Mina, trapped in a Chinese restaurant’s bathroom overwhelmed with the smell of the former’s shit — have the grossest meet-cute in any remotely mainstream film this side of the Farrelly brothers. What many would’ve played solely for gags or foreboding is instead a clever mixture; just that they’re getting along so well during this should be a sign that something isn’t quite right. The fact that it’s captured in a six-minute static shot is less a noxious declaration of formal principles than the careful establishment of tone, mood, and psychological reality.

As notes of discontent begin to arise — Mina’s parents are gone, Jude is sexually selfish, there’s a fair deal of hesitation about their (sudden) marriage — the film suggests inescapability by jumping forward in time through simple crossfades, and these notes only grow louder until, finally, it establishes a long-term sense of chronology. It’s by this point — when Mina and Jude are married, with a newborn child, in an Upper West Side apartment — that Costanzo lets sequences play out for more than a few minutes at a time, often as small games of tug of war that offer neither an upper hand nor true points of vilification. Mina may be crazy, yes, but her actions are clearly laced with good intentions, and Rorhwacher’s fragile performance — defined by trembles of the body and pitch changes in her voice — suggests a damaged person, not a malicious force, and the justified anger in Jude’s reaction — represented by Driver’s natural intensity as a performer, something perhaps never harnessed more effectively — creates a dichotomy in which no pleasantries can be sustained.

This is a strong recipe for domestic drama, and as is sometimes the case with closed-off films of this sort, attempting to balance an insular existence — and, in the case of half its leads, an intensely insular worldview — with the perspective of the outside world is when Hungry Hearts most clearly falters. Another matter of reactions: is the notable deflation during these segments — from doctor visits to interjections by Jude’s concerned mother — a negative effect of the strong center even being toyed with, or is it, more simply and more damningly, that these moments are often conveyed with less sense for human behavior and dramatic current? The deeply troubled third act — which travels to an entirely different location and boils down the struggle to something more schematic, even physical — would suggest that it’s the latter. It’s especially a shame that the picture’s flirtations with being something truly special are cut into by histrionics, some that even cast a shadow on its sexual politics — in effect, coming closer to a portrait of “hysteria” than genuine psychological dread.

Ultimately, though, it’s a credit to Costanzo, Cianchetti, Driver, and Rohrwacher that what precedes and, in the case of a very brief denouement, follows a miscalculated segment can stand strongly enough in the memory to retrospectively render these blemishes less significant. The film that’s left in my mind is still one of intelligence, force, and an acute sense of dread — enough to shock a good deal of audience members willing to bend to its peculiar rhythms.

Hungry Hearts is now in limited release and available to stream.