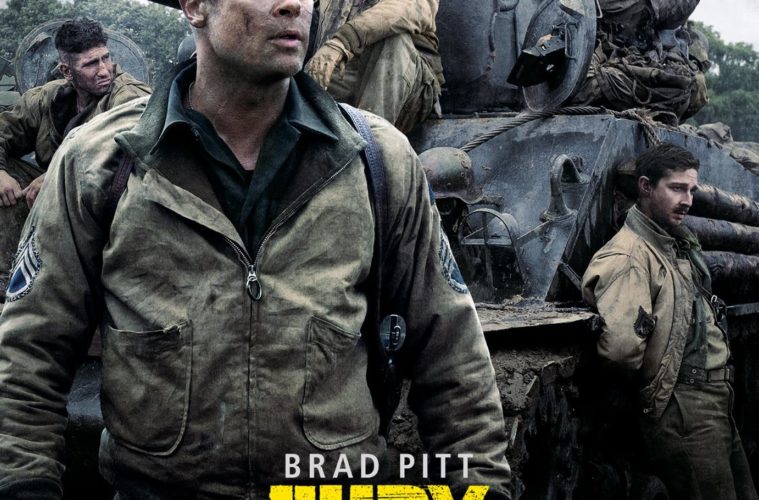

The year is 1945. An opening title card states that “every man, woman and child” have been mobilized to kill the Allies. David Ayer’s latest film, Fury, spends much of its time making a case for why we should care about the members of the five-man tank crew at the center of this film. As led by Wardaddy (Brad Pitt), the tank and its operators are in disarray. In the film’s potent opening, Wardaddy transverses a battlefield of broken tanks and machinery on horseback. It’s here Ayer where finds the film’s most poetic image — the durability of animal over man — and it’s a moment that capitalizes on the presence of its star to imbue Fury with some compelling point of reference.

Harder to pinpoint are the motivations or characterizations of gunner Bible (Shia LaBeouf), loader Grady (Jon Bernthal), and operator Gordo (Michael Peña). It’s clear they’re suffering from PTSD with no outlet. A chunk of face belonging to their fallen brother is the sort of gory reminder that fuels their rage and frequent outbursts of masculinity. “History is violent,” Pitt’s character proselytizes, and Fury wants us to believe these men are complex. Many of Ayer’s characters in urban crime films (e.g. End of Watch and Harsh Times) are characterized by the same struggles, products of a deadly environment. Fury, however, is quick to introduce newbie Norman into the crew. As played with unrelenting earnestness by Logan Lerman, the man is everything his new comrades are not. He’s trained to type sixty words a minute, not gun down Nazis. As Pitt and company offer Norman the often-uttered advice of “do as you’re told and don’t get too close to anyone,” the tank company transitions from damaged underdogs to people that are hard to like.

They utter phrases like “meat per bullet” as they gun down hordes of faceless enemies. My own withdrawal from this behavior isn’t a matter of conservative opinion versus liberal opinion. Fury’s violent decapitations and exploding torsos feel exploitative or, worse, uninteresting, because the film never quite earns the dramatic stakes it strives for. It doesn’t help that, plot-wise, Fury is a series of small missions. There isn’t one objective the tank is striving for. This forces us into the routine and rhythm of the band of brothers. The personalities are on display, and the banter / repeated catchphrase of “best job I ever had” is most interesting when it comes from LaBeouf’s character, Bible. This may be the actor’s most interesting role. Far away from the one-dimensional scripting of the Transformers franchise, LaBeouf gets to mull over questions like whether or not God loves Hitler. It’s a compelling turn in an increasingly ideologically convoluted film.

If Norman is meant to be the eyes of the viewer, our viewpoint into brutality and camaraderie, it’s unfortunate that the character is headed for such a simple apex — the moment where he, too, can gun down the bad guys and yell “fucking Nazis!” Pitt reminds us, though, that “a lot more people got to die,” and a lot certainly do. The final set piece of the film finds the tank in another impossible situation, holding off an entire battalion of Germans. If the scene unfolds with steady and precise tension, the emotional payoffs here are again hindered by the muddy morality that has troubled the rest of this film. While the vehicular fighting is initially impressive on a technical level, it becomes numbing to watch wave after wave of SS extras get gunned down and not revert to some way of thinking about the latest Call of Duty game.

Pitt, who abandons the grandiosity and theatricality of the more interesting Aldo Raine from Inglourious Basterds, gives a stark performance here. The film finds Pitt playing another commanding patriarch like he did in The Tree of Life, stripped of any playfulness or charisma the actor is usually known for. His best scene — and, as it so happens, the best scene in Fury — is a prolonged dinner sequence of moral ambiguity. Norman and Wardaddy have taken refuge in the company of two young and lovely German ladies. This reprieve from violence into consensual sex, good food, and music is interrupted by the other members of the tank. They drunkenly parade around the room, grope the women, and, in the film’s most despicable moment, spit on their food. Wardaddy, despite his name, brings a resolution to every act of aggression his men offer. He swaps his clean food for the woman’s dirty one. He can tolerate the brutality around him (to a certain extent), but never gets to the core of why it has to be that way. Fury shares this plight: it leaves viewers with plenty to mull over — action scenes, a strong core of actors, and visceral moments — but lacks the moral compass to guide us through it all.

Fury hits wide release on Friday, October 17th.