Few filmmakers capture people hanging out quite like Richard Linklater, who has so many features revolving around convivial moments that it would be easier to list the films without them. As early as the rambling chance encounters of his breakthrough, Slacker to the recent drug-and-booze-fueled amateur philosophizing in Everybody Wants Some!!, Linklater has remarkable eyes and ears for elevating digressions that many other artists would treat as trivial into invaluable character- and world-building moments without sacrificing their inherently relaxed mood. It is appropriate, then, that the best parts of Last Flag Flying, a loose sequel to Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail, are those centering on casual conversation organically unfolding between the leads, chatter that often intensifies into poignant drama or devolves into genuine hilarity, photographed in simple-yet-striking shot-reverse-shot and two-shot configurations. What’s troublesome is that Linklater relies too heavily on these setups as his primary source of connection to the main trio, while the storyline and themes (many of them trite) from he and co-writer Darryl Ponicsan, who have adapted the latter’s 2004 novel, thus suffer.

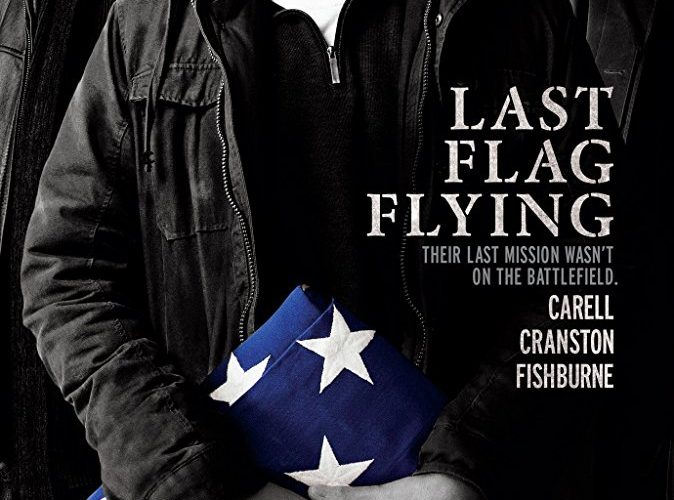

The film begins with Larry “Doc” Shepherd (Steve Carell) as he seeks out his old military pals — the rambunctious, insubordinate reprobate with a heart of gold Sal Nealon (Bryan Cranston), and the reformed miscreant-turned-reverend Richard Mueller (Laurence Fishburne) — in hopes that they will accompany him to bury his son, Larry Jr., who was killed in action during the onset of the Iraq War in 2003. In their travels from New York to Arlington to Delaware to Boston, back in New York again, and ultimately to Doc’s native New Hampshire, this trifecta of aging Vietnam War veterans face numerous roadblocks, whether it’s as simple as misunderstanding the convoluted mandates of the United States military’s funerary process or as severe as learning the devastating truth about Larry’s demise.

Viewed primarily from Doc’s perspective — the first shot being a bird’s eye view that cranes downward to follow Doc as he enters Sal’s bar, positioning him as Flag‘s main POV — the ensuing journey provokes many questions and beliefs that arise in the wake of tragic loss, Sal and Mueller representing differing viewpoints of the grieving process. Sal is the well-intentioned devil on one shoulder, a non-believer with no conception of an afterlife, let alone spiritual salvation, proclaiming that loss must be dealt with directly (“Pain is pain,” he attests); Mueller is the faithful, moralizing angel on the other, believing that God will save Larry Jr.’s soul and give Doc the strength to carry on and praying Larry will experience a “God moment” akin to what turned Mueller away from his old ways.

Cranston brings a boisterousness to his role (originally played by Jack Nicholson) that is often charming, but at times excessive, at worst coming off as a pale imitator of the legendary actor. Fishburne is a more quiet tempest who erupts only after Sal pushes his buttons to the point that his theological armor is pierced and “Mueller the Mauler” of yore returns, at least temperamentally. Carell delivers the most fascinating performance of the bunch, going from timid gregariousness to grief-stricken despair, all of it cloaked by his outwardly affable demeanor. And this reveals one of the film’s biggest problems: Doc is too often forced to the periphery by the histrionics of Sal and Mueller, yet the proceedings are so rigidly rooted in his pathos that character-defining moments come across as contrived, leaving little room for much examination of Sal or Mueller beyond, respectively, their barely touched-upon alcoholism and dark past.

What brings the trio together, aside from Doc’s request, is a shared trauma involving one Jimmy Hightower, a former corpsman who was fatally wounded during their time in Vietnam — an occurrence about which they continue to feel deeply guilty, for their platoon were so addicted to morphine that they exhausted their supply and left Hightower to die in extreme agony. Toward journey’s end, they stop at the home of Hightower’s mother (Cicely Tyson), and their prior ruminating on the woes of aging is at the forefront as they confront the living legacy of their past trauma. This sequence should be compelling. But all of its gravitas is lost with the objectification of Hightower’s mother, who is given so little screen time that she essentially serves to function as a morality pet for the troubled men. It ends as quickly as it began, carelessly tossing aside what could have been a touching moment for all involved.

Similarly ineffectual are Last Flag‘s repetitious, maladroit political commentary that squanders nuance via sheer redundancy. When Doc observes the capture of Saddam Hussein and subsequent deaths of his sons on a bar TV, he wonders aloud if their sacrifice was worthwhile — a question he’s also posed about the death of his own son. It’s a naturally affecting moment, yet Sal quickly adds levity to the situation with a cheeky aside that significantly neuters emotional heft. Other politically charged scenes do manage to land, such as when the trio must enter a concealed Air Force hangar to see the body of Larry Jr. and each notes how the government isn’t allowing pictures of caskets to be released so as to avoid fueling opposition to conflict in the Middle East. This occurs near the start and seems an appropriate observation for these characters, as are later parallels they draw between their FUBAR experiences in Vietnam and those in Baghdad expressed by Larry Jr.’s best friend, Corporal Washington (J. Quinton Johnson). Nonetheless, these sentiments start to appear more frequently, each becoming less incisive as they ultimately reiterate ideas that have already been expressed.

Last Flag Flying aims to be a somber meditation on friendship, war, and loss, and is held back by its devotion to a rote three-act structure and political critiques that might’ve seemed forward-thinking when Ponicsan’s novel was released in 2004 but are simply self-evident in 2017. It doesn’t ruin the legacy of The Last Detail, nor does it necessarily expand upon it — perhaps a challenge of following-up an already excellent film with a trenchant script by the great Robert Towne — and no amount of alterations to characters’ names and backstories can truly set it apart from the earlier movie. When playing into Linklater’s significant strengths as a director of actors, the film is able to entertain and evoke sincere feelings from its audience. Last Flag Flying manages to end on a high note in concluding with Larry Jr.’s final known words and end credits underscored by Bob Dylan’s wise and weary “Not Dark Yet.” Would that what came before shined as brightly as its resolution.

Last Flag Flying premiered at New York Film Festival and opens on November 3.