In 1970, David and Albert Maysles unleashed their seminal documentary Gimme Shelter. The brothers captured the violent events at the 1969 Altamont Speedway Festival with the Rolling Stones playing out an era of “peace and love.” Gimme Shelter is molded into a masterful set of images and moments that are explosive, dangerous, and alluring — much like the music of rock ‘n’ roll. Throughout their celebrated and prolific career, the Maysles siblings explored vast worlds, a portrait of American salesmen or the reclusive world of society’s elite in East Hampton making for some of their most iconic works.

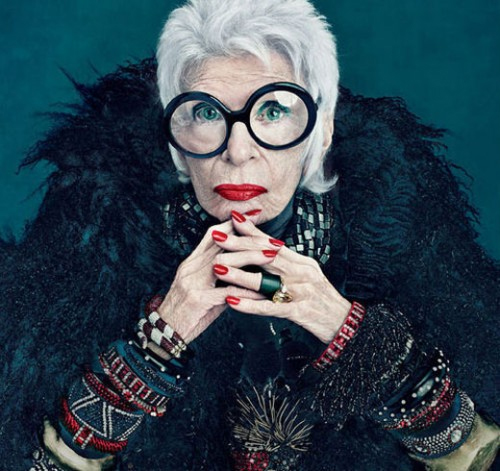

Forty-four years later, without his brother David, Albert Maysles is still an expert at showcasing the world of the iconoclast. Iris is proper evidence. As a subject, Iris Apfel is a magnetic presence: revered in the fashion industry, immortalized by museum curators, and even impressing Kanye West. Thick glasses take up most of her face. The rattling produced by her jewels, necklaces, and gaudy wristbands provide a metronome for the soundtrack. Maysles pairs sensory images of fabrics and trinkets with Iris’ youthful ideology. “Individuality,” she says, “is not intellectual. It’s all gut.”

The film is interspersed with quick interviews from an ensemble of notable fashion figures. Everyone from Dries Van Noten to Bruce Weber are eager to praise Apfel’s style, but Maysles’ visual infatuation with these creations best explain why she’s a fashion legend. Iris spends her days thrifting for unusual “pieces,” designing window displays for upscale retail stores, and managing her interior design company. Patterns and colors have dominated her and her husband’s daily life. The film’s introduction of Carl, Iris’ 99-year-old husband, is another compelling thread.

Carl, eager to play sidekick to Iris eccentricities, is equally fascinating, though more reserved than his wife. He admits his wife bought his pants on a live morning show program, suggesting to viewers that he’s never quite escaped the influence his wife has. His defining features are flippancy and candidness. Iris sometimes has to be gently coerced into exploring the darker territory of her life — broken hips, along with the sadness and inevitability of age — while Carl is eager to recount their struggles. He is quickly silenced by Iris when he begins describing what they faced when decorating for the White House, a job they started when “Truman was there.” Maysles is adept at finding the strange rhythms this longstanding marriage has adopted.

Iris offers an entertaining view into the artistic process, encroaching mortality, and societal trends. The “Rare Bird of Fashion,” Iris, would be quick to argue that’s too much credit. The film builds and adds to the myth of a figure many outside the niche world are unfamiliar with. My favorite moments in Iris are the moments that are usually removed from other documentaries. Iris is eager to break the fourth wall and talk to Albert Maysles as he films her. She talks about the ladies that hit on him at fancy Upper East Side parties and offers him food. Maysles, powerless to respond, lets the camera roll and validates Iris’ wise word: “if you hang around long enough, everything comes back.” The time Maysles has spent with this compelling figure results in the return of a great filmmaker.

Iris premiered at NYFF and is seeking distribution.