There are many images throughout Inherent Vice that even the most perceptive eyes couldn’t describe with total confidence. I speak as much for the specific (color, shape, interactions between certain elements) as I do of the broad (why we’re seeing something from a particular angle, or what significance it might even hold — if there is any), and it’s to the film’s credit that this guessing game, for all its coinciding frustrations, never lapses into the boring. Perhaps more impressive is what mileage this conceit earns: it’s early enough that one realizes this, more than anything, is a visual translation of author Thomas Pynchon’s notoriously difficult prose stylings. If familiar words take on new meaning with little more than slight adjustments of syntax, discomfiting even the best-read minds by jutting out from seemingly ordinary sentences, there’s no reason a responsible visual stylist shouldn’t follow suit.

The seventh feature of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career introduces itself with an ostensible key — not only to what we’ll see, but how we should see it. The first scene’s classic detective-yarn set-up — I’ve no doubt you know it well: a detective (Joaquin Phoenix’s Larry “Doc” Sportello) is approached by someone (Katherine Waterston’s Shasta Fay Hepworth) looking for help — is futzed with at first glance and every opportunity. Standard expository dialogue is jettisoned, mostly in favor of short, half-clipped sentences that the stoner PI, toking on “the new package,” is sometimes mumbled and mixed to the point of inaudibility, and what should be specifics of the case emerge from people’s mouths as broad generalizations entirely concerning people we don’t know — far too many names for this stoner PI to sort through, at least.

“Don’t burden yourself with what we’re about to see” is the basic message here. He’s played this early trick plenty times before: it’s not so different from Magnolia‘s early embracing of coincidence, how The Master preceded its slate of ambiguous qualities with a Rorschach test, or in the way Punch-Drunk Love introduced unexpected, violent-chaotic incidents with a sudden, context-free car crash. (Anderson would corroborate the idea, lest you think I’m just surrendering right away.) That Anderson would construct his most visually muddy film when making the first big-screen adaptation of a notoriously difficult author is admirable. His fidelity to the written word is just as understandable, given the esteem of who’s being translated; less certain is the strength of this choice.

Alas, Inherent Vice’s key folly is an inability to reconcile piece and whole: hit the mark as a drug comedy (sometimes screamingly so) and work wonders with its seemingly untenable ensemble though the picture certainly does — I never thought I’d see a Joaquin Phoenix-portrayed, dopey PI snort coke courtesy of a Martin Short-embodied, manic dental-industry magnate; it works wonderfully, regardless — the picture is so often and so violently oscillating between extremely dense narrative trappings and shaggy-dog set pieces that its form, no doubt to be called “loose-limbed” by many, runs the risk of becoming (and sometimes succumbs to being) bled-out.

While a film so big and (for better and worse) complex need not be pegged to single components, it is still with zero reservation that I lay much blame at the feet of voiceover provided by Joanna Newsom’s Sortilège. It’s not so much a question of whether this device complicates an already-knotty narrative by piling more of Thomas Pynchon’s sticky language onto the adaptation’s hazy images, but what value is gained from turning this ancillary figure into what is essentially Thomas Pynchon himself. The reams of text she’s reading to us bear a disconnection from much else that’s happening onscreen, floating over and explaining events instead of, a few unreliable-narrator intrusions with the images excepted, truly digging into them.

What aggravates more is that the images are a true inter-medium translation of complicated text, more frequently than not able to speak for themselves so profoundly and so lucidly on their own terms. Roiling under the drugged-out surfaces is a strangely regret-laced ode to the California that almost was and apologia for what it was becoming in 1970. Fiction be damned, Gordita Beach’s places and people stand as some of (if not the) most personal expressions of Anderson’s own background: constant superimpositions melt images into each other, a wild stream / smear of confusion, and his more-or-less trademark tracking shots — especially one involving Doc, his old flame, and a California street — imbue scenes (that, in most hands, would merely be connective tissue) with a sense of time forever lost. “It’s our future that got fucked,” Vice tells us, not spinning the same hippie sob story that’s long failed to carry any more water; the small tragedies of passing time, the valuable things forever lost, can’t be anything but collective.

It’d be fine if things didn’t go much deeper than a subdued mourning of cultural loss or bizarre coherence of formal elements geared toward earning a hearty laugh. (What results from the framing, delivery, and bit of dialogue revolving around Lt. Detective Christian F. Bigfoot Bjornsen’s [a staggeringly perfect Josh Brolin] preference for eating pancakes at a certain restaurant should be hung in museums.) Perhaps that categorization-resistant combination of generational swan song and an endearing dumb-smart mindset redeems the lulls, particularly during its draggy expository sequences — more a fault of too much narrative material and intrusive voiceover than specifics of the plot itself. Perhaps these flaws can be taken as an opportunity to surrender only further to various gags and the tempo of Jonny Greenwood’s light, rock-influenced score, which bleeds into the various soundscapes so well it becomes difficult to notice. There are simply too many instances where it’s hard to care about more than an image, a line, or the curious ways in which its ensemble cast will intersect.

Not that this problem is so outstanding when witness to Anderson’s greatest display of formal elasticity. What’s been hyped as a return to earlier Altman stylings, as well as something of a veer into Coen country — comparisons that have followed the source material since its publication in 2009 — isn’t necessarily inaccurate, albeit something of an insufficient way to assess the property. Unfortunate as it is that the notice of extensive visual gags have been fairly exaggerated, a spare production design — mostly empty rooms, kitchens, offices, and restaurants; it’s only boisterous when boisterousness could be logically applied — frequent use of the much-missed two-shot, and, in the spirit of The Master, extensive use of close-up (often taking a bottom-up perspective) evince a mutual confidence in performers and visual rhythm.

This late into his career, the conversation about Anderson as a formalist is fairly unified: both a towering example of the current American cinema and, more importantly, one who embeds insinuations into these gestures that extend past sensory satisfaction. That’s not to say he’s grown complacent. These slow-burn, extended-take conversation sequences, the wide-shot pratfalls, the willingness to create ugly images — I do believe it is intentional; too much of this film looks beautiful to make sense of a strange mistake, and what some will take as “mistakes” are clearly dictated by a drug-hazed text — and various forms of narrative-questioning trickery (notice the Punch-Drunk Love-esque lens flares during a post-gassing conversation: not everything can be clear-cut to a druggie’s brain) evince something all the more exciting: a well-established artist opting to dig their way through new forms of filmic manipulation. Fewer words from the people onscreen would bring this film toward the sublime.

Inherent Vice is too bewitching a film with too many small corners of pleasure — all from a director and author who are too ambitious in their respective fields not to earn the benefit of a little doubt — for yours truly to disregard. How unfortunate that some of the curiosity it engenders is a result of landing in that fascinating “worst film from a great director” category. Yes, Paul Thomas Anderson’s continued output enriches the medium, and we should be thankful when, such as here, he extends past the boundaries of what a healthy, much-studied career might lead most to expect. If only the final result had a little more stability.

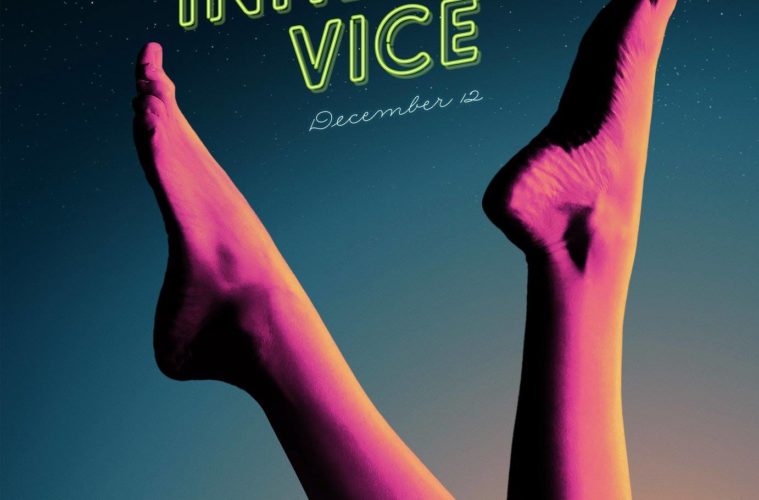

Inherent Vice premiered at NYFF and will enter limited release on December 12, followed by a wide release on January 9.