Distinct from musicals, music biopics, and documentaries, fiction films about the challenges faced by musicians in practicing their craft have been around since the earliest days of cinema. From The Jazz Singer and A Star Is Born to recent releases such as Not Fade Away and Inside Llewyn Davis, the tribulations of musicianship have long fascinated filmmakers and audiences alike. Although these struggles are typically emphasized for dramatic purposes, rarely is the viewer subjected to the downward spiral of one of these artists for the overwhelming majority of the runtime, let alone with such intoxicating lucidity; a feat that Alex Ross Perry’s Her Smell accomplishes with flying colors.

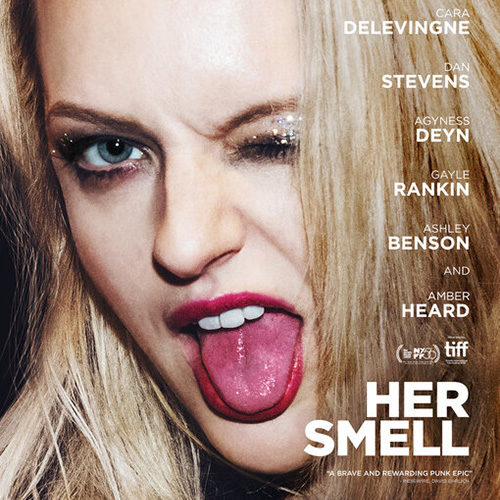

Becky Something (Elisabeth Moss) is the frontwoman of Something She, a famous indie rock trio in the vein of iconic riot grrrl groups like Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney. It becomes immediately apparent that Becky has almost completely lost her grip on reality, strung-out on drugs, wielding her fame and success like a flail, alienating those close to her: bandmates Ali van der Wolff (Gayle Rankin) and Marielle Hell (Agyness Deyn) as well as her estranged ex-husband, Danny (Dan Stevens) and her caring but concerned mother (Virginia Madsen). Her Smell follows her decline into egomaniacal psychosis over the course of five protracted scenes, bookended by performances at a New York venue owned by her begrudging manager, Howard Goodman (Eric Stoltz). While the film primarily focuses on Moss’ character, Perry has assembled a veritable ensemble cast of actors, veterans and newcomers alike; each thoroughly characterized regardless of their importance to the film’s central character study. While contained location-wise, it’s the largest production yet for the writer-director, with four out of the five acts featuring no less than six performers on-screen at once, each expertly blocked and delivering their frequently florid lines with surprising deftness.

Moss is the obvious standout here, portraying Becky’s self-destructive dirge as if it were a Shakespearean tragedy, spouting idiosyncratic, nearly incoherent monologues and wandering off to partake in ludicrous new age rituals led by a spiritual guide she keeps on retainer, much to everyone’s chagrin. Perry himself has corroborated this comparison, saying in an interview that he wrote the film as a cross-section between Shakespeare and Guns N’ Roses. Glimmers of Becky’s authentic personality and backstory shine through sporadically, each chapter being preceded by a 4:3 digital home video showing Becky and her bandmates toward the start of their illustrious careers—simpler, happier times where the rock and roll took precedence over the vices inherent to the lifestyle. Longtime collaborator Sean Price Williams returns as Perry’s cinematographer, wringing every weathered visage and grungy backstage mise-en-scène of all their energy, his camera dizzily drifting from room to room as if in a drug-fueled haze accompanied by eerily discordant ambience up until the show-stopping fourth act.

Oddly enough, for a film ostensibly about a musician and her band, there’s a noticeable lack of music in the proceedings, saved for moments when the interpersonal drama reaches its zenith such as the aforementioned bookended intro and outro as well as a deeply moving scene in which Becky plays Bryan Adams’ “Heaven” on piano for her daughter. This melancholic performance comes during the previously mentioned fourth act, after Becky has hit rock bottom and confines herself to a small rural estate to rehabilitate for a significant amount of time. By this point, Something She have been broken up for a while with Becky having gone clean and her bandmates moving onto other projects—all except Becky herself. “Who is Becky Something? A way to hide from Rebecca Adamchek,” she proclaims with mournful clarity, demonstrating the drastic difference between the person she is and the persona she was. The music and raucous droning having finally ceased, and the film becomes exceptionally quiet. Williams’ camera, having been initially roaming through a series of long takes, is now locked into place by a tripod and the erratic editing has adopted a far more tranquil structure. Becky has left her rock and roll life behind for a calmer one where she can dedicate more time to her own well-being as well as that of her daughter, having grown considerably in the interim. Here is where the film’s ideas truly click into place and the story of Becky’s nervous breakdown transforms into a one of sacrifice and redemption.

The film builds to a final sequence that’s beset with suspense as Becky skirts by the temptation to use again, punctuated by the sudden return of the assailing ambient score, suggesting that a relapse could be just around the corner. Her Smell goes beyond the expected trappings of your usual rock drama and successfully manages to capture the convulsive core of musical artistry while suggesting, in a major departure for the usually cynical Alex Ross Perry, that it’s possible for the individual to break free of its corrosive bonds.

Her Smell screens at the New York Film Festival and opens on April 12.