Roger Corman is an interesting character. He’s a provocateur, a goof, a “schlockmaster,” a great assembler of talent, an independent film legend, an international film buff, an under-appreciated master of concepts and execution. All of these sides are shown in Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel, director Alex Stapleton‘s new documentary that attempts to reconcile all of these disparate character traits and titles into one cohesive piece. And, happily, he mostly succeeds.

The film is a combination of Hollywood luminaries relating to the audience what makes Corman so unique through talking head interviews mixed with a mostly-chronological telling of his story to inform us of what exactly we should be admiring about him. The crux of the story seems to be that he is under-appreciated not only amongst the film elite but also from an entire new generation of film fans that grew up without drive-thrus or grindhouses (alas, the closest thing we’re likely to see are three-hour-long homages to his work courtesy of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez).

In keeping with the title, we meet Corman in his rightful environment: on a movie set in Mexico, shooting the new movie Dinoshark for the SyFy Network (that name will always be regrettable…and I don’t mean Dinoshark). He’s producing that film with the same energy that he likely expended on the 394 other films he’s produced, not to mention the 56 he also directed over a career that has spanned more than fifty years.

Corman’s World is a healthy mix of interviews in stock footage, clips from his films, and a wide array of talking heads from former employees Ron Howard, Martin Scorsese, Peter Bogdonavich, John Sayles, Robert DeNiro, Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, and the man who steals the show, Jack Nicholson. All of the interviews have a fun vibrancy to them that match the goofy and loose nature of a Corman film. Ron Howard is walking around almost aimlessly as trees fly by in frame, Jonathan Demme seems trapped in the back of a car, dogs are running in and out of one interview as the bells on their collars going off mid-answer, and, well, just having Jack Nicholson on camera.

Most of their participation is centered around annecdotes and strange lessons learned on a Corman set (Bogdonavich’s directorial debut is an especially odd and hilarious experience). Nicholson was arguably his longest employee amongst the collected, acting in, writing, and directing movies with Corman for nearly a decade. This gives the audience the wonderful gift of relying on someone so entertaining to dole out a good deal of the story. To hear him relate the experience of working on The Terror is worth the price of admission alone.

With all my praise thrown on Jack, I’d be remiss to not give some to the film’s subject. Corman, an affable man with a warm smile and a great wit about him, built up an empire through all kinds of violent, bizarre, and otherworldly films. To track his career of micro-budget independents is a lesson of popular film culture for the better part of three decades.

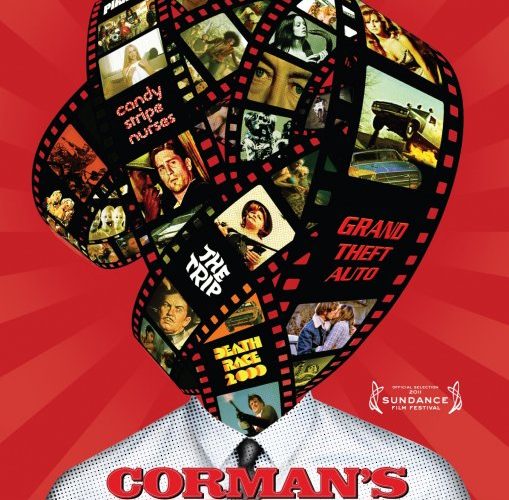

Getting his start with black-and-white science fiction films in the late 1950s (Attack of the Crab Monsters), he moved on to a series of middlebrow adaptations of Edgar Allen Poe films (House of Usher) that gained some critical success (which, to be frank, probably means “any”). He went with the teen culture in the ’60s before any of the big studios understood that there was an audience there (The Cry Baby Killer) and moved swiftly with those kids into the counter culture of the mid-to-late sixties, with films like The Wild Angels (with real Hell’s Angels!) and The Trip (written on real LSD!). Then he was off to grindhouse exploitation, both black (The Big Doll House) and otherwise (Caged Heat), finding the new “R” rating as liberating rather than limiting; the more breasts and blood, the happier his audience.

And that is pretty much where the good times, and the story, ends. We get a nice introduction to Roger’s wife, Julie, another capable producer, and the two set off on a partnership on set and off. There isn’t a lot of time spent on what happened to both Corman’s life and his work (by now he had been running his own production company, New World Pictures, for a dozen or so years) from when the Corman-esque blockbusters hit until the present. It is disappointing on an emotional level, as we only see him when things are generally doing well and avoid his direct-to-video days, but that doesn’t seem to be the point. There is also a nice section where he gets rightly awarded which is rather sweet indeed.

The film is completely and wholeheartedly an appreciation for the work of Roger Corman and, in that way, is something both needed and essential. He’s made an unfathomable amount of films at a time when, even with digital technology, there are people who call themselves “film makers” who have yet to make a movie at all (like this writer) when he would crank out a shoot in two days. It’s his fearlessness, his dedication, and his ability to trust young filmmakers and actors that is unheard of in a century of film work in America. In one of my best experiences so far at the New York Film Festival, the screening got a lot of hearty laughs and a well-deserved round of applause from the hardened NYC critics as the credits rolled. Roger Cormon deserves a document in his name, and luckily it’s as fun and irreverent as one of his own creations.

…And the gratuitous nudity and blood in the clips didn’t hurt, either.