In the opening scene of Olivier Assayas’ 5 and a half hour epic Carlos, a man we don’t know wakes up in a bedroom, kisses a naked woman goodbye, walks outside to his car, checks the car for any attached explosives and steps in inside. The car explodes.

It is a cold, calculated and brutal opening to a film that, in many ways, is just that: a cold, calculated and brutal look at the life of a terrorist. In combining the verite style of Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers with Steven Soderbergh’s stubborn first-person telling of one man’s story in Che (our antihero is in nearly every shot), Assayas offers his viewers little space to breath, or hide, from the primary subject.

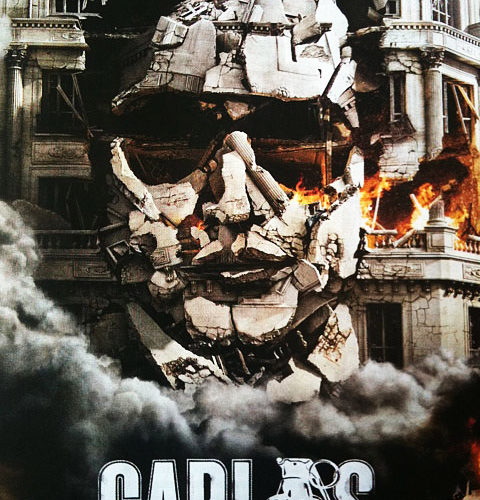

That subject is Ilich Martinez Sanchez, a.k.a. Carlos the Jackal (played by Edgar Ramirez), the infamous Venezulan terrorist who fought for several “anti-imperialist” causes over two decades before being captured in Africa and sent to prison for life. I put anti-imperialist in quotes because the film clearly does, Assayas determined to mark the evolution and eventual devolution of a freedom fighter who runs out of freedoms to fight for.

We meet Carlos as he joins the PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), keen on making good impressions. He’s young, handsome and strong; a charmer with women and revolutionaries alike. He’s also vicious. Seconds after a lunch with a fellow PFLP member, Carlos walks down the street with a bomb in his hand. He opens the front door of a packed bank and tosses the bomb inside, walking away with only a slight pep in his step as it explodes.

This is a ruthless man, and one who very much believes that revolutions are won not with words but with actions. He says as much, more than once, in the film. He quickly makes friends, then uses them for the good of the PFLP. He quickly beds women, then uses them for the good of the PFLP.

Soon, the PFLP notices, and Carlos moves up the ranks. And, unabashedly, Assayas follows Carlos, into the depths of this business. A colleague, detained in a French airport, gives Carlos up. The traitor proceeds to bring the French cops to Carlos’ hide out. What happens next is violent and unflinching. Assayas is wise to hold-fast to his well-groomed style of long, moving takes. His viewers are in the room with Carlos and the innocent people he has tried to blend with. But, unlike these bystanders, we move with the camera, which is everywhere, capturing everything from Carlos’ bullets ripping through the cops to his cigarette burning quickly into his lips. For a brief moment after Carlos has fled and the cops have fallen, the camera stays with the bystanders, pseudo-intellectuals sporting their French culture while condemning their French government. We know how Carlos feels about these people: dreamers, not doers. Fakers, consumed by the ideals he bleeds for but not ready or willing to bleed themselves.

It’s a romantic notion and one that has survived millenniums, justifying one revolt after the other. The more important question, it would appear, is how does Assayas feel about these people?

Unlike Che, Carlos wades into the idealistic psyche of its title character. This is less an account of events, more of an exploration of them. Nowhere is this more clear than in the middle hour of the film, in which Carlos and his PFLP crew kidnap a room full of OPEC representatives and boards them on a plane. On this plane we watch Carlos turn from idealistic freedom fighter to mercenary. By now he’s been dubbed “Carlos The Jackal” by the international press and the recognition has clearly gone to his head. He speaks of his childishly simply hopes for an anti-imperialist world the way vain actors speak of their influences during an Oscar speech.

He voices these opinions to the Saudi Arabian OPEC representative – the very man the PFLP has hired him to kill. After days on board, flying to Algiers to Tripoli and back, Carlos, strung out and without sleep, makes a deal. Taking $20 million U.S., he agrees to release the hostages, including the Saudi Arabian he was sent to execute. His crew members fight against it, but the decision is made. To being called a traitor he scoffs and reasons the money is for the PFLP, and causes need money like that to survive. While history has never proved that this transaction occurred, it’s key to the film and a well-crafted turning point for an extremely dynamic antihero.

Driving away from the incident, with flash bulbs bursting to capture a photo of The Jackal, Assayas makes sure we see Carlos pose.

Ramirez is in complete control of his character and the long chronicle of his life. His physical transformation impressively matches his emotional one, as Carlos goes from young and ambitious to tired and lazy. After completing a mission early on, Carlos is sent to hide out for a couple of weeks. The next scene sees him 20 pounds overweight with an unkempt beard and the hair of a cave man. He explains that he doesn’t handle inactivity well. No kidding.

Apparently Ramirez is the same way. There’s nothing inactive about the man’s performance. Every cigarette he lights up (and there are a lot over the 5 and a half hours) has something behind it. Weight loss/gain has always been a “sign” of a great performance for many – proof that this particular thespian tried really hard. In this case, the assumptions are more than true.

The last hour and a half of the film finds Carlos traveling from port to port in order to escape extradition for his past crimes. As fewer and fewer European countries agree to take him in, Carlos finally flees to Sudan where he is captured by the French government. It is this final act that lingers on to the point of insanity. We fly with Carlos and his broken family from place to place, watch him yell at them for his own transgressions and drink himself into a stupor. He still has sex, but not as well as he used to. And he’s not that handsome anymore. He’s more of a punchline than anything else.

We’ve traveled with this man to the bitter end. His frustration is our frustration. It’s a bold move by a bold filmmaker, and Ramirez is more than willing to take the trip. Hopefully this is the beginning of a beautiful princess.

8 out of 10