In its 49th year, the New York Film Festival boasts a wide-array of striking and rightfully heralded cinema, including several foreign-language Oscar hopefuls. Among this exclusive few is A Separation, the awe-inspiring drama from internationally acclaimed Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi that has already won the prestigious Golden Bear for Best Film at the 2011 Berlin International Film Festival, as well as acting awards for its four adult leads. I rarely list accolades in reviews, but out of fear the film’s deceptively simple premise may not entice, I want you to understand the incredible poignancy and power of this truly remarkable film.

In its 49th year, the New York Film Festival boasts a wide-array of striking and rightfully heralded cinema, including several foreign-language Oscar hopefuls. Among this exclusive few is A Separation, the awe-inspiring drama from internationally acclaimed Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi that has already won the prestigious Golden Bear for Best Film at the 2011 Berlin International Film Festival, as well as acting awards for its four adult leads. I rarely list accolades in reviews, but out of fear the film’s deceptively simple premise may not entice, I want you to understand the incredible poignancy and power of this truly remarkable film.

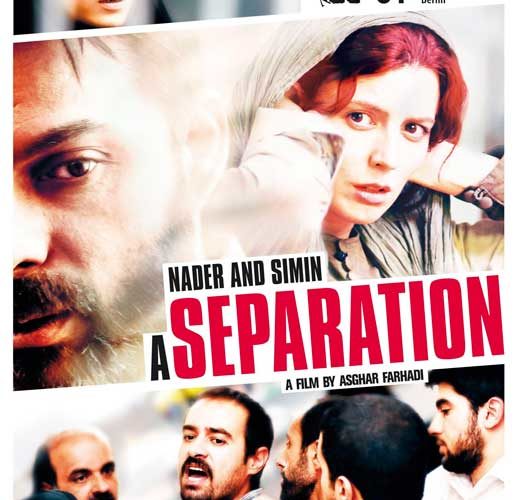

The story centers on two married couples: Hodjat and Razieh (Shahab Hosseini and Sareh Bayat) who are blue-collared and devout Muslims, and Nader and Simin (Peyman Moaadi and Leila Hatami) who are wealthier and far more secular. Their differences are immediately apparent from from the wives’ chosen attire. While Razieh religiously wears the full body-concealing veil called a chador, Simin wears a stylish headscarf and dyes her hair a bold red. Yet despite their class and religious differences, their paths fatefully cross when Nader hires Razieh to care for his Alzheimer’s afflicted father while he is at work.

This was once the duty of Simin, but she and Nader are now on the verge of divorce. After much work, Simin has finally secured visas that would allow them and their 11-year-old daughter Termeh (Sarina Farhadi, daughter of the director) to leave Iran for the United States, a place Simin feels will offer more opportunities for her bright child. But if they emigrate, Nader would have to leave his senile father behind, which he cannot bring himself to do. All of this is quickly established in the first scene, where Simin lobbies unsuccessfully for a judge to grant her a divorce. Shortly thereafter, she prepares to move back with her parents and pleads with her daughter to go with her. But Termeh is a devoted Daddy’s girl, and will not leave her father. And so Razieh becomes a new facet in their home, coming a long way by bus with her young and precocious daughter Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini) to clean the house and look after Nader’s father. Before long a conflict arises over Razieh’s caretaking techniques resulting in an incident that irrevocably changes the course of both family’s lives forever.

From here the drama hinges on a he-said/she-said device. But rather than this becoming a spiteful narrative where one character (and thereby class) is painted as the good or bad, Farhadi is careful to never provide an easy out. His actors expertly craft complex and compelling characters that may do bad things but can never be easily written off as bad people, much less villains. Shahab Hosseini embodies recession-era rage as an out-of-work cobbler who feels helpless without the ability to provide for his family. Bayat is heartbreaking as a woman who struggles to live a life according to strict religious principles even if it puts her family’s well-being at risk. Hatami is mesmerizing as a mother willing to abandon her best friend/husband in sacrifice to her daughter’s future. And Moaadi is unforgettable in his portrayal of Nader as a devoted son and father, pressed to his breaking point when these loyalties threaten his marriage.

From here the drama hinges on a he-said/she-said device. But rather than this becoming a spiteful narrative where one character (and thereby class) is painted as the good or bad, Farhadi is careful to never provide an easy out. His actors expertly craft complex and compelling characters that may do bad things but can never be easily written off as bad people, much less villains. Shahab Hosseini embodies recession-era rage as an out-of-work cobbler who feels helpless without the ability to provide for his family. Bayat is heartbreaking as a woman who struggles to live a life according to strict religious principles even if it puts her family’s well-being at risk. Hatami is mesmerizing as a mother willing to abandon her best friend/husband in sacrifice to her daughter’s future. And Moaadi is unforgettable in his portrayal of Nader as a devoted son and father, pressed to his breaking point when these loyalties threaten his marriage.

When these four are thrown before the Iranian justice system and coaxed to testify and blame each other, each is forced to make impossible choices. All around the acting is superb. And while Farhadi is rightly praised for being a talented actor’s director, his filmmaking mastery is most evident in the film’s restraint. Scenes crucial to the characters’ testimony are shot abstrusely or not at all, leaving the audience to play detective and decide for themselves what really happened. It’s a device that pulls you in and doesn’t let you off the hook. As characters enter murky moral territory it becomes impossible to snidely judge their choices. There are no easy answers to be found in this morally ambiguous drama, and the questions linger beyond the credits that roll over the wounded characters awaiting resolution.

I was awe-struck by A Separation on every front but want to draw special attention to one of the film’s most powerful dynamics: the father/daughter relationship between Nader and Termeh. Through Moaadi and Sarina Farhadi’s magnetizing onscreen chemistry their bond is instantly clear and key; the push and pull of it quickly becomes the film’s most engaging element. Termeh is a child who is soon to be a woman, but her emotional maturity is unfairly rushed when her family is threatened. She is forced to see Nader as not only her loving father but also as a man who is capable of grave mistakes. It’s a cruel awakening crucial to growing up, but seeing this realization cross her countenance as she stands before a judge is absolutely devastating. Like her filmmaking father, ingénue Sarina Farhadi deserves wild praise for her work here. She is brilliant in every moment of her portrayal of Termeh, down to her final critical close-up. A Separation can understandably be classified a detective story, a thriller, a divorce drama and an Iranian Rashamon, but I will always remember it as one of the most compelling coming-of-age films I’ve ever had the pleasure to see.

While A Separation is slated to open in the U.S. in limited release on December 30, 2011, I fully encourage those of you in the New York area to see it at NYFF this weekend. You won’t regret it.