It’s a particularly amazing experience watching a film from the 1930s and feeling as though it’s doing things you haven’t seen before. Such is the case with Fernando de Fuentes and his acclaimed Mexican Revolution Trilogy, which will screen in succession at this year’s New York Film Festival, from Sept. 29th through 30th.

De Fuentes, now regarded by all cinephiles as a pioneer in his own right, was born in Veracruz, Mexico, studied Philosophy at Tulane University and returned to Mexico as a poet/journalist. He was nearly 40 years old when he made his first film El Anónimo. Of course, his worldliness paid off in spades. Especially when it came to putting the Mexican Revolution to celluloid. De Fuentes’ second film, El Prisionero 13, would be the first of his revolution trilogy.

And while Prisionero appears to be a giant leap in ambition from the romantic triangle melodrama that is El Anónimo (de Fuentes’ second film is a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions) it lacks just as much subtlety and provides just as much melodrama. Where it excels, however, is in the subject. During the revolution, de Fuentes was an assistant to Venustiano Carranza de la Garza, who would become the Mexican President after the regime was overthrown. This close proximity to the action clearly informs both the tone and the characters of El prisionero 13 and the two films that followed.

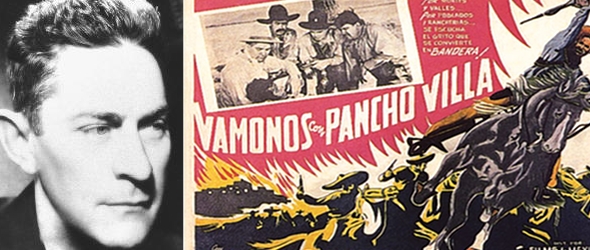

Yet, despite the director’s rebel roots, there is a universal, comic cynicism that ultimately survives in his trilogy. In El prisionero, a corrupt general unknowingly sentences his estranged son, now a revolutionary, to death. In the final film in the trilogy, Vámonos con Pancho Villa!, six villagers join with Pancho Villa’s famous band of soldiers, earn a reputation as the fiercest warriors in the bunch, gain the nickname “the lions” and subsequently die, one by one, tragic, silly completely avoidable deaths, leaving the leader Don Tiburcio Maya alone: a man with no friends and nothing left to fight for.

But where de Fuentes’ well-rounded musings come through most poignantly and most successfully is in the second (and best) film in the trilogy, El compadre Mendoza. Fuentes tells the story of a man, Rosalio Mendoza (Alfredo del Diestro), who, during the Mexican Revolution, plays both sides, alternatively praising legendary rebel Zapata and Victoriano Huerta, commander of the military. Upon the arrival of either group of soldiers to his estate, Mendoza’s servant replaces photographs of each side’s leader in the study. He proceeds to throw parties for either side, providing them with

Of course, this continuous lie catches up with Mendoza, who is forced to chose a side by film’s end. Like all three films in Fuentes’ revolution trilogy, El compadre Mendoza starts, more or less, as a comedy. The duel life the land owner lives is played for laughs, and the parties he throws are raucous and full of life. As the laughs fade so to does our hero’s demeanor. He forms a relationship with a revolutionary, who, in turn, falls for Mendoza’s wife, the daughter of a government supporter.

This comedy, slowly but surely, devolves into the dramatic, playing out like the best ending Flannery O’Connor short story ever could – politically aware, yet completely aware of the contradictions of both sides of the line.

On a technical level, Fuentes did some revolutionary things. Time lapses occur in their crudest form, usually while focused on objects in Mendoza’s house – in one instance, a painting of Zapata dissolves into Huerta. Fuentes’ camera moves with a fluid grace few other filmmakers of the time could match. Consider the opening shot of the second film: it begins in the dirt, tracking the footsteps of soldier’s boots. First one pair, then two, then the we see the entire regiment stumbling up to Mendoza’s estate. There’s nothing special about the acting or the location of the estate. It’s the way Fuentes unflinchingly finds the focus of the scene, without splicing the film. The 180 degree rule (one wonders if it was even a “rule” back then) is broken purposefully and to great effect, forcing the viewer to wake up and reassess the frame in front of them.

By the time Vámonos con Pancho Villa! starts rolling, you’ll have seen enough of Fuentes to be convinced of his cinematic importance. Unfortunately, Pancho Villa isn’t cause for much more evidence. Over-long and unforgivably heavy-handed, the film’s rag-tag group of brave peasants are never developed enough to care about while its climactic scene, as even-handed as any of Fuentes’ three films, is far too convoluted to take seriously. That said, the battle scenes on display here are breathtaking, the camera literally riding with our men as they take on the government baddies. Nothing in El compadre Mendoza touches this kind of visual ambition. If only the narrative execution of the third film could compete with the second.

All three films screen next week at NYFF.

Have you seen the films of Fernando de Fuentes? Are you a fan of his Mexican Revolution Trilogy?