Chapo Trap House listeners—of which there are, by magnitudes, more than nearly any podcast that has ever existed—know host Will Menaker as progenitor of Movie Mindset, with which Film Stage readers could hardly be more simpatico. His Twitter is as likely to sound off about something recently watched as it is the latest antics and horrors of contemporary America—two things sometimes inseparable, of course, but Menaker’s enthusiasms are well-stated and direct enough to take wholesale. Peep his Letterboxd and it’s a whole other ballgame: a clear statement on Movie Mindset as the finest way to live.

As a longtime Chapo listener I could hardly have been happier to talk with Menaker about his favorite films of 2022, the lines between political thought and pure enjoyment, and his fascinating, Philip K. Dick-like theory on how art shapes the world around us.

So said Menaker as we got underway:

“Keep in mind that this is a little bit incomplete because there are some movies from this year that I have yet to see. I haven’t seen The Fabelmans yet; I haven’t seen Decision to Leave. There could be some spots open to add to my best-of-the-year list as I check off more of those boxes. These aren’t ranked, either. You can take these all, basically, as equal—this is just in the conversation for me as my favorite movies of the year.”

His rundown, with the occasional comment from me, follows.

Mad God (Phil Tippett)

This is a movie that I think deserves to be championed, to be seen and heralded more widely. It is a stunning, stunning work of art. It is Phil Tippett’s—the God of stop-motion animation—30-year labor of love to produce what is, basically, a trip to Hell. It is a stunning vision of Hell. It’s self-contained, two separate odysseys deep into the bowels of the inferno, but—at the same time—contained in the movie is a metaphor for the creative process and art in general: going through Hell to produce and find your soul. To find something transcendent. I was really moved by this movie.

There is so much goop in this movie. One of my favorite tweets of all-time is JucheMane’s “goop on ya grinch recontextualizes bodies in spaces”; Phil Tippett’s Mad God is Goop on Ya Grinch: The Motion Picture. Shout-out to the great director Alex Cox, who is in the movie as one of the only human figures. I loved seeing him show up. I loved the World War I-era gas masks. This elevator trip into the absolute bowels of damnation; these tortured, miserable wretches and this canvas of suffering and humanity. But—like I said—contained within is a really beautiful, transcendent message about boiling away, through the horrors of the world, something transcendent: this grain of beauty that exists amidst the horrors of existence.

You forget a new movie, independent or otherwise, can be this disgusting.

The animation is so beautiful, despite that [Laughs] what it’s depicting is so grotesque and monstrous. I’ve never seen anything like it—the fact that it’s stop-motion and, like you said, all independently made. It took him 30 years to do it.

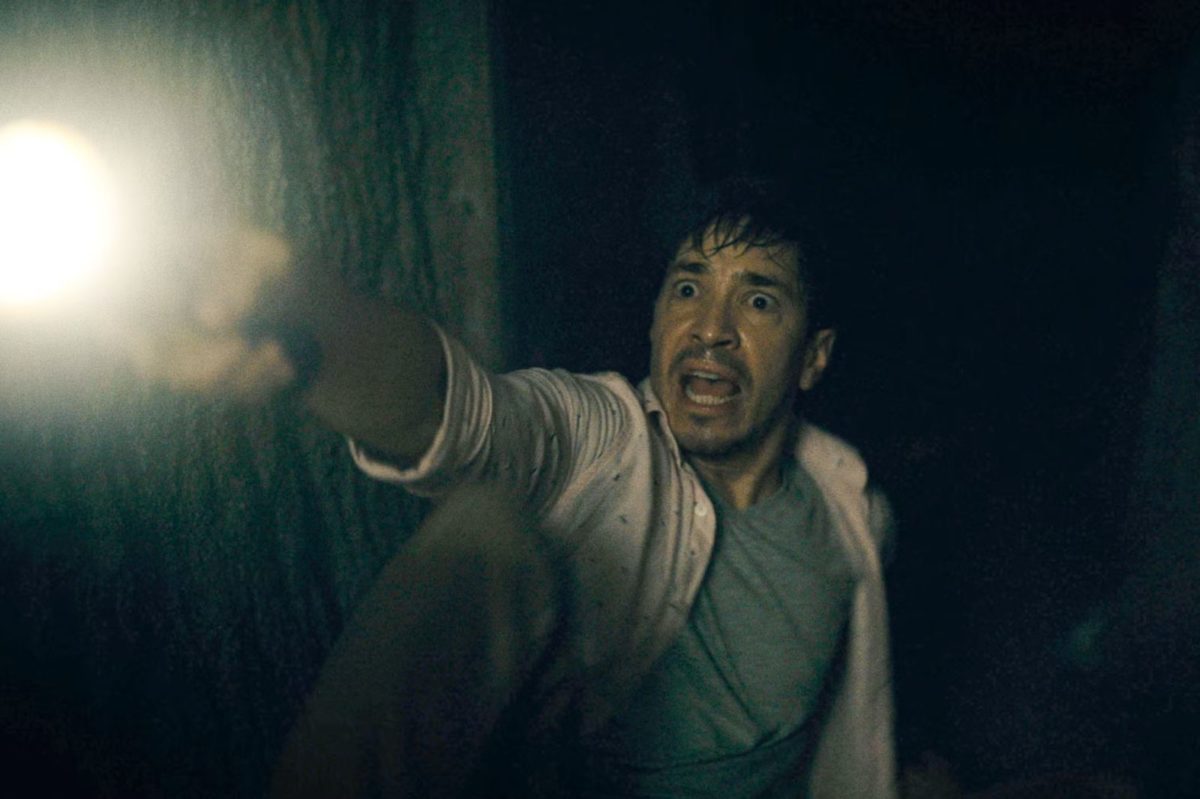

Barbarian (Zach Cregger)

Best horror movie I’ve seen in years; perfect movie-theater experience. Genuinely terrifying, genuinely hilarious. The hard cut to Justin Long and the tape measure scene had me ROLLING. Wears its influences lightly, but Cregger knows what he’s doing. May be the first successful “post-MeToo” movie.

Crimes of the Future (David Cronenberg)

The idea that David Cronenberg could make a movie in 2022 and it wouldn’t be on my best-of-the-year list is simply insane. But he’s still got it. Crimes of the Future I think, strangely, might be his funniest movie—not an adjective I usually use to describe the work of David Cronenberg, but there was something very humorous here. Another movie about making art, about artists. I know he wrote this movie a while ago, but I think how uncannily, when I’m leaving the theater, it’s a movie that really feels like living in 2022.

Not in any describable, simple 1:1 way—“people are changing their bodies in weird ways.” The coldness of it, this uncanny feeling we all can’t quite put our fingers on: that as the borders between our bodies and technology are becoming policed, we begin to question what is and isn’t appropriate. These questions have been present forever, but more than that I think it suggests that we all are becoming something other than human. “Post-human,” or something. I don’t think there’s necessarily a moral judgement contained in that, but it is happening. The ending is almost a hopeful one: we all just eat the plastics. That’s it! We’ve made the plastic; it’s not going anywhere; it’s in our bodies right now. So what if we just eat all the shit we create after technology, and we become technological, biological entities?

It’s so summative. Even though he’s working on a new film, it would function beautifully as a final statement. There’s real privilege in witnessing that as it happens.

What I love about Cronenberg is: the ideas he’s playing with are very similar, and he returns to the same themes, but the variations on them are so satisfying. And like I said: what I love about his movies is you walk out of the theater like, “I don’t quite know what to make of that.” And a day later, a week later, months later you realize—like the microplastics—it’s just worked its way into your body and nervous system and you can’t stop thinking about it.

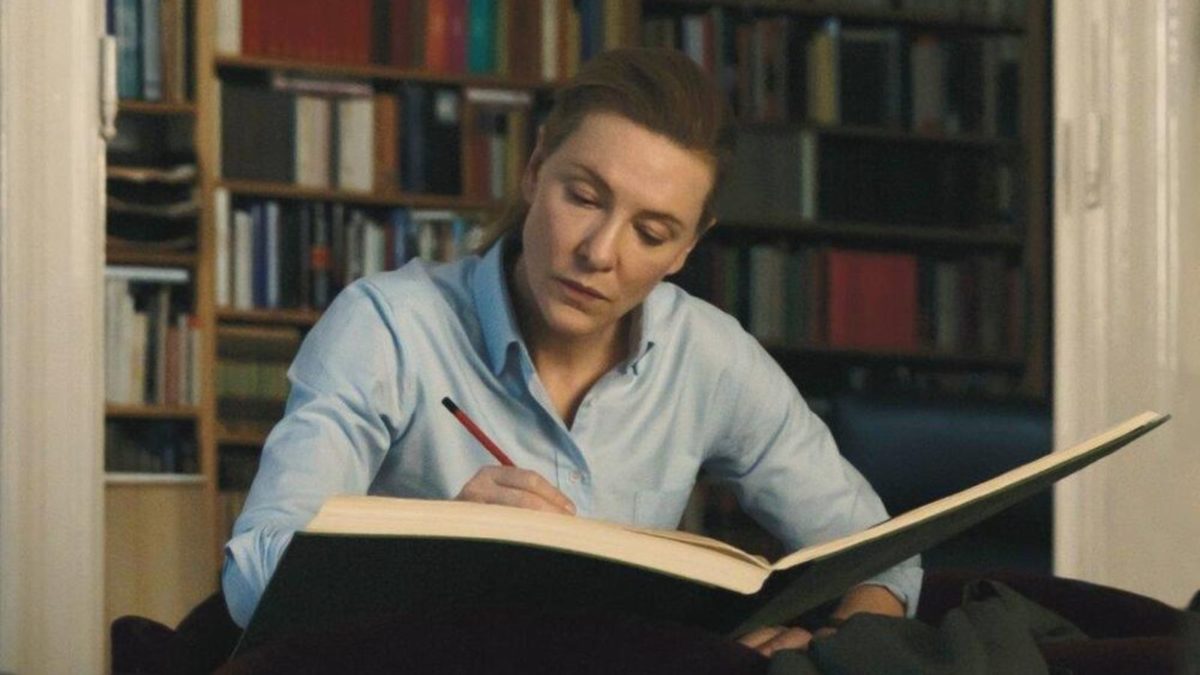

TÁR (Todd Field)

I saw it pretty recently and I tried to avoid reading anything about it; it seems like one of those movies you should see as blindly as possible, which I think helped. But at the same time I couldn’t help being aware of arguments and debates over the movie—just the general contours of the plot—and what I was most impressed with was: I’ve never had a bigger gap between the movie I saw and the movie everyone was apparently talking and arguing about. Going into it I was expecting some cancel-culture, #MeToo morality tale. And it couldn’t not be anything further from that. Our boy Nick Nightingale learned something from Stanley Kubrick: this is a very dry comedy and, some would say, ghost story as well.

I have my own theories about this movie. There are multiple competing and equally valid interpretations of what is really going on. I was watching it for, like, 90 minutes, just asking myself “What is this movie? What am I watching here?” It began to gel as the movie goes along, but I’ve come to the position… you remember when this movie first came out and all these people were upset to find out Lydia Tár wasn’t a real person? Especially with that Adam Gopnik-New Yorker scene; I can’t tell you how on-point that scene was, from my experience in the publishing industry. The first 30 minutes or so of that movie just felt so uncannily real, but in that I think it contains the artifice of what’s really going on here. I was pleased by the whole “Is Lydia Tár Real?” I think that’s exactly the right question to ask about this movie, but not in the literal way.

I don’t think Lydia Tár, in the movie, is a real person; I think Lydia Tár is the fantasy projection of the woman who killed herself in that movie. The woman who killed herself: you only see her hair, from the back, in the Adam Gopnik scene. Even when Lydia is looking at her obituaries her hair obscures her face. You never see the face of the woman who killed herself. Going back to The Shining: this is a movie about the vanity of artists and writers, people in the creative field. What’s contained in the movie is not necessarily reliable, but it’s an artist’s view of themselves.

Like I said: there was something artificial about the first half of the movie, and it struck me how excessively successful Lydia Tár is. She’s an EGOT winner. She’s Leonard Bernstein’s protégé. She’s the most-respected conductor in the world. There’s something of a tell there for me—this is the career of someone fantasizing about being the most-respected, most-loved classical-music conductor of all-time.

I like this. I’ve literally never heard it expressed.

I think the Slate article about it did a good job. From the point she falls down and hits her head is when reality begins to interject itself, and what you see in the last third is Lydia Tár’s fantasy of herself. I’d take it a step further than that. It’s a movie I feel like I shouldn’t even talk about until I see it a second time, because watching it again would unlock. But Cate Blanchett: she’s one of the GOATs. It’s got that very, very dry, subtle dark comedy. I appreciated that.

The Banshees of Inisherin (Martin McDonagh)

The most depressing movie of the year; another movie my appreciation for only grew the more I talked to other people and thought about it. I’ve been hot and cold on Martin McDonagh but this was perfect for him. I didn’t really like Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri because I thought he was straying a little too much into commenting on a Red State America thing and Donald Trump, which I think is a little outside his wheelhouse. But this, going right back to Ireland, this psychological portrait of the Irish mind—he nails it. It was so funny, so sad. Colin Farrell: one of the best performances of his career. He’s kind of playing against-type. Usually his characters are a bit devilish, witty, roguish—just a handsome, cool guy—and in this movie he’s playing, as one of the characters says, “One of God’s good guys.” He’s just not quite smart enough to realize how lonely he is, and when Brendan Gleeson breaks up with him he has to confront the fact that he is lonely; this is his life.

This is two competing visions of male loneliness. Brendan Glesson—once again—the artist character; the vanity of that. “I’m better than just spending every day of my life, like clockwork, showing up at the pub, talking about the same bullshit to the same people until I die.” He’s like, “I need to be remembered. My art needs to live on.” Colin Farrell is happy to go to the pub every day, to talk to his donkey. And also: I have not seen EO yet. People are saying it’s the donkey movie of the year. I’m very interested to see it, but I would like to see if EO gives a better donkey performance than Jenny—sweet, sweet Jenny. One of the most moving performances I’ve seen this year: Jenny the donkey and her relationship with Colin Farrell.

It’s a good study of a perpetual Chapo concern: loneliness.

“Do all my friends hate me?” It’s a fear everyone has. I think this is a psychological portrait of Irish Mindset. I also love, as an American, this fictional portrait of the Aran Islands, which are tiny islands off the coast of another tiny island. An even more distilled version of the stubbornness, the grudges. Just shackled to the Catholic church. Here’s another thing I loved about Banshees: up until about 20, 30 minutes into the movie, until Colin Farrell very clearly looks at a calendar—or they make reference to the Irish Civil War—only then you realize it’s 1923. This movie could’ve taken place in 1823 or 1975. Nothing has changed in rural Ireland. [Laughs] It’s out of time itself.

And what I love is, from the perspective of an American watching this movie—especially American white people who love to romanticize Ireland—a lot of how it’s filmed is this stark beauty and bleakness of the Irish coastline. “Oh, this is the Emerald Isle! Look at how beautiful it is. Stone walls bisecting these rolling green hills.” Yeah: it’s beautiful because you don’t live there! Try spending a year of your life living there and telling me how fucking beautiful it is. You’d be losing your fucking mind.

And I really love the performance of the sister, Kerry Condon. I thought she was wonderful. She can’t even go to the pub unless her brother brings her. That’s how fucking backward it is. You can’t even get a pint without a male companion. Her loneliness is the fact that she doesn’t have nine kids already makes her some sort of threat to the community order. Whereas Colin Farrell or Brendan Gleeson don’t have families that we know of or see—they’re just two lonely guys. It’s this idea of: because the sister is also lonely she’s ostracized from that community and has to make the decision to get the fuck out of there first chance she gets. Just go to a slightly bigger island next door.

Colin Farrell is a nice guy, but the movie does ask who’s being more cruel to who. It’s a movie about cruelty and kindness, because obviously Colin Farrell is this well-meaning doofus and Gleeson is very masochistic to himself. But who’s being cruel to who? Colin Farrell continuing to insist to not get it and asking “what are you doing this Saturday?” is also kind of sadistic, in its own way. Or the first time he tries to be cruel he does [Laughs] the meanest thing ever by telling him his mom is dead.

Top Gun: Maverick (Joseph Kosinski)

I mean: come on. Tom Cruise: Mr. Movies. He’s saving movies. Top Gun: Maverick—what more can I say? Is it as good a movie as the original Top Gun? No, because the original Top Gun is Tony Scott, Jerry Bruckheimer, this beautiful California dreamstate of the orange glow of the sun and this ‘80s, cocaine movie blockbuster perfection. But Top Gun: Maverick is an incredibly solid movie—way better than it has any right to be—and surpasses the original in one way, one crucial way: the quality of the action scenes is like nothing I’ve never seen before. Actually flying those fucking planes. Pulling real Gs. Say it rips off Star Wars—I don’t give a shit. It was absolutely thrilling. Tom Cruise: he’s done it again, folks.

Avatar: The Way of Water (James Cameron)

Virtually no chance this would not end up on my list, but I’ve got to say: I liked it more than the first. A lot of the first was dedicated to explaining the concept of an Avatar—Jake Sully’s real body vs. his Avatar body. We can put that aside and just start the movie. It should be called The Way of the Whale.

Did you like the whales?

The whales are the best part of the movie. The scene where that whale just slams into that fucking boat—just plops on it, just crushes, like, sixteen guys. This is a movie where I don’t even know if you can call it “special effects.” These are no longer special effects. If Tom Cruise is the God of Movies, I don’t know what that makes James Cameron. God Emperor of Movies? He has bridged the uncanny valley. Even when the first one looked incredible, there was still that slight, fingernail-sliver in my mind looking at the Na’vi—a little corny. In this movie it’s completely obliterated. At no point was I like, “This is all digitally generated.” The whole middle-third is a David Attenborough movie about a place that doesn’t exist. Without any explication or exposition, the scene where the whale just starts talking in subtitles: in any other movie it would be eyes rolling in the back of my head. With this one I was just like, “Yes. Perfect. This makes perfect sense.” And by far the most emotionally moving part of the movie was that whale.

And if you talk about a Cameron movie you’ve got to talk about the top-, top-quality ownage. Extreme ownage. Pump-your-fist-in-the-air, audience cheering. Avatar is a movie about the evil of military imperialism and industrial exploitation of the natural world, but because it’s Cameron: goddamn, all those space marines and ships, all the whaling technology—everything just looks so cool. Ever since Aliens, ever since I saw the ship landing on LV-426, this is what takes you back to being a kid loving sci-fi movies. The crab mechs on the whaling ship. The personal submersible. Edie Falco in that quick little mech suit working out, sipping the coffee. It’s just all of his fetishes about being like, “This is evil, imperial future military-industrial technology… but goddamn, if it isn’t cool.”

It’s hard to imagine who else can pull that off.

Any criticism you level at it for being corny, clunky, or offensive in the way it portrays indigenous culture or whatever—for my money you can throw that. Even if you are inclined to credit them, throw it all in the trash because you get to spend three hours on Pandora in a cinematic spectacle by one of the few people who’s taken the ball down the field in a way nobody could have predicted, only he could do. Again: this is a paradigm shift in what movies are capable of accomplishing.

RRR (S. S. Rajamouli)

My de facto movie of the year. I’d put it in the same conversation with James Cameron and Avatar: The Way of Water because this is a movie that announced for me—at a time when people have a very moribund view of movies and the cinema as a major, popular medium—a better action movie, a better superhero movie than anything I have seen come out of America in the last 10 or 20 years. RRR is the closest thing to a live-action anime I’ve ever seen. I was totally unprepared from the first scene—a three-hour movie that felt about five minutes long. There is no scene in cinema that felt as transcendent to me—I was levitating off my scene as I was watching it—than the “Naatu Naatu” dance-off in the middle. A throwback to a different era in moviemaking, of musicals, of spectacle. The joy and music. The dancing. The two lead actors were just… like I said, something that announced movies still have something genuine and special about them, that has an ability to move and affect you in a way no other artform can.

Did you see it in the theater?

I did not, unfortunately. Believe me: I would have loved to have seen that in southern India where people were setting off fireworks inside. That is a movie I would love to see if it comes back in theaters; I would love to see that with an audience of people.

You have a Letterboxd list about Movie Mindset. What about that list embodies the lifestyle? Is it just a collection of favorites, or does it encapsulate something greater?

This is the first clue to what Movie Mindset is all about: Movie Mindset is anything I want it to be at any given moment. There are no rules, really. I didn’t have much of a criteria. I was just trying to put together what I thought were 50 of the greatest movies of all-time—or just movies that mean a lot to me. This is a course in my taste in film, really.

You’ve hosted events, done Q&As. I’ve seen you at screenings and been sure to keep distance because the last thing you need is another listener bothering you. So I’m curious how you prefer to watch: a nice home set-up, or is it more of a theatergoing exercise?

Obviously the Cadillac movie experience is seeing it in the theater with other people. There are certain strains of thought that hold that if you don’t see a movie in the theater it doesn’t really count. I kind of respect that, but at the same time: if a movie is truly great you can be watching it on your phone and the effect is the same. So most movies I watch are in my living room. I don’t have a truly special set-up; I have a nice TV and soundbar and comfortable living room with some cats. There are certain movies that I guess I would feel disappointed if I hadn’t seen them in a theater, or if I’d rented them or seen them on television I think, “Man, I wish I’d gotten to see that in the theater.” For repertory programming there are movies I go back to and see in a theater that have been really great experiences. There is something you can get—that dreamlike state in a theater that can’t be replicated. But I don’t think the power of movies is contained only in the cinema itself.

Have you seen anything in repertory recently that felt sanctified?

I saw Big Trouble in Little China at Metrograph; I saw The Shining last year at IFC. Any Carpenter / Kubrick movies I didn’t get to see projected on the big screen, I think you do get an added layer of effect. I’d never seen The Shining projected on a big screen before and was like “Okay, this is what it’s for.” It was like a religious experience.

Obviously the show’s listener base is huge, its social-media following no less. As a podcast host and active poster—who’s also doing this list for us—is there ever some advocacy goal?

Yeah, absolutely. I guess I consider myself “a movie fan.” I don’t know if I’m a critic. I’ve been paid to give my opinions about movies, I write about movies—I suppose that puts me in “the conversation.” Look: nobody needs me to ring the dinner bell for Avatar: The Way of Water. [Laughs] For less-heralded filmmakers like James Cameron or Tom Cruise. For a movie that I haven’t seen a lot of people talking about, like Mad God, I just want to share my enthusiasm about movies that I like or think are worthwhile. Sometimes those are movies everyone’s going to see regardless. I don’t try to find things I think are less-well-known and use my platform; if that does occur I think it’s very nice. I just like sharing my enthusiasm. I love talking about movies; it’s one of my favorite things to do with my friends.

If I’m going to use my platform to talk about something: the great movie podcast right now is the LexG Movie Podcast. If I can promote anything, it would be the LexG Movie Podcast. I just have an enthusiasm for movies and am not trying to be strategic about it. Back to this idea about Movie Mindset—and I’ve been asked to define Movie Mindset a lot of times—the joke about it is: like Chapo Trap House, it’s a name I created to mean nothing. It’s intentional drivel. Movies as nootropics.

It started as my attempt to be a satirical lifestyle influencer: “Better living through watching movies.” But the more I’ve thought about it, there is a germ of truth there. And I think it comes from this idea I had that movies are more real than reality, in many ways. Movies can’t change reality. I’m very much opposed to this idea of art and movies—especially now—being some morality programming; I very much hate the idea of artists as social workers.

I don’t think you can change the conditions of the present through art or getting people to watch the right art or abide the right messages through art. But I do think art has the ability to, if not change the future, I think… I have this kind of sci-fi concept that art is how we receive messages that are transmitted from either our future selves or future human beings into the past. I think the art made in the present moment can only be really discernible with the benefit of hindsight. The messages that art creates are tapping into a frequency, but messages that are being beamed backwards in time. So there’s a hope, maybe, that you can change the future, but I think you can only understand the present in the future.

Yeah, I see that. My own version is experiencing the “same” art at different stages of life, and from one experience to the next it may as well be a completely different entity.

An artist may have an intention or idea, but that’s only the beginning. Whether you want to call it some universal consciousness or that we are being consciously… it’s like this Philip K. Dick idea of Valis: that we’re receiving this signal from something, from some form of intelligence being beamed into our heads. Through the illusion of light and shadow, the artificial animation of motion and sound and images contain some sort of signal that a different intelligence is communicating to us.

But I think it only goes backward in time. I think the people who create it, at the moment you’re seeing it—you only get part of it. Rather than tell the truth about the present moment… movies made in the present can tell the truth about the past, but movies made in the present are telling the truth about a future that hasn’t happened yet.

It makes me think of your interview with Alan Moore about Eternal Return.

Yeah, absolutely. Alan Moore: my shaman, my wizard. I’m very much influenced by his thoughts and philosophical context, in his novel Jerusalem, about Eternal Recurrence. You can’t change the past or the future—it’s already happened and we’re living it over and over again, probably trillions of times. There’s a very grim fatalism there, but I think is also reassuring in a lot of ways.

I appreciate that you can talk about films from a perspective either political or not.

We did a Top Gun: Maverick episode and people were like, “How can you hail this work of military-industrial, fascist propaganda over an anti-imperialist movie like RRR?” All I would say to caution the audience on that is: yes, I will support any work of fascist military propaganda if it’s cool enough. But also be a little careful with what the politics of RRR really are. Maybe just investigate a little bit [Laughs] who’s being canonized in the last dance scene. It didn’t affect my love for that movie one iota.