Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2022, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

It was a year of unforeseen 180s. When I saw Elvis at Cannes, I thought it was awful, but I couldn’t get it out of my head. Two curiously voluntary watches later, I craved its glam-camp radiance. When 2022 began, Blonde was one of my most anticipated movies. When it ended, I’d watched 363 films, nearly 200 new ones, and only three-fourths of Blonde, a slog to end all slogs (if only). In the first three weeks of December, I watched 2-3 movies a day. In the last week, I didn’t watch anything, the longest stretch of cinemalessness I’ve endured since 2015.

Statistically, I watched ~25 more movies (~50 hours) than I did in 2021. Elvis, EO, and JFK were my most rewatched at three times each, thwarting my yearly habit of obsessing over one or two movies with 5+ watches. Am I maturing, spreading my taste more widely, or simply falling out of touch with obsession? I watched more Cronenberg than any other director, more Pitt than any actor, but the latter started to sour on me by year’s end. I think of myself as someone who mostly explores films, new or old, that are new to me. But those are two of my all-time most-watched, begging the question: did the pandemic-wrought rise of comfort food ever fall?

On January 7th, I met someone while out dancing. I’d end up at her place half of the year. That same month, she’d introduce me to the ballet. Enamored, I’d end up there five more times. We’d live what, for the better, felt like four-years-in-one together, countless nights spent intertwined on a couch under the glow of movies.

At the stroke of midnight on October 21, listening to “Let Me Roll It,” I turned 30. The decade I’d waited so impatiently to enter greeted me with a viral hope––the strangely felt promise of creative and communal fertility. The next night, I had my first birthday party since my 7th-grade soirée, when Pat Walthall slapped Lexi Hall while she was frozen, absolutely obliterating the mutual trust required to play a game of freeze tag and sending the party spiraling into an exodus of parent pickups. This party was better: no parents.

On behalf of a fresh decade––one I already felt more accustomed to than the last––I tried something new: a screen playing a favorite film in every room. In total, across five screens, 12 movies played, including Eyes Wide Shut, Short Cuts, Breaking the Waves, and Irma Vep to highlight the 90s contingent. Few things this year were as memorable as turning into my kitchen to see a pixie-cut Nicole Kidman naked in the bathtub with a young Cameron Bright next to a delightfully oblivious group of five. Little did they know she was not his mother. You can find the full list of what played on what screen in what order here.

Precious time spent with my international film fest family at Cannes, Venice, and NYFF was as invigorating as the films we went to see. (Rankings from the fests linked above). I felt, as I have every time I’ve left Cannes, that things had tectonically shifted in the world. Whether placebo or not, that collective global anticipation of film is a fantastic contagion, a gift of a new imagination, an intercultural communion, an unimpeachable fuel to live fully. Conversely, virtual Sundance faded from memory in days.

Albert Serra’s Pacifiction, a Cannes competition debut, was my true number one watch (twice) in the calendar year. It races through my mind daily. But it won’t arrive stateside until 2023, so it gets an extra year of stewing before tempting listicle fate, as do many others worth mentioning: Rewind & Play, R.M.N., Showing Up, The Kiev Trial, Master Gardener, Other People’s Children, Paris Memories, Monica, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Personality Crisis: One Night Only, Scarlet, Will-‘o-the-Wisp, and Unrest. Keep your eyes peeled, folks.

As I love to say: there are no bad years in cinema. It’s just a matter of what you choose to watch. Top ten at the box office? That’s a no from me, dawg. Top ten at the Amy Taubin’s year-end Artforum list? Now we’re opening some doors. In the 21st century, a year in cinema is so vast you couldn’t cover it all if you tried. So, don’t settle for mediocrity. Don’t settle for what’s most loudly marketed, especially if it’s shit.

Explore the world of film. Dip into more interesting streamers, like MUBI, Kanopy, and The Criterion Channel. Cut out distractions while you watch. Open yourself up to the film in front of you. Mentally and emotionally engage with it. Find critics you appreciate (not necessarily agree with) and follow their coverage for recs. Look up directors of your past favorites to see what they have cooking or which directors they love. Search for films that magnetize you, films you fall for, films that affect how you live your life or challenge the way you think about the people around you. They’re there, waiting, hoping to be found.

To spotlight all the genuinely worthwhile films I saw this year (think: 3½-5 star range), I’ve gone the Top 50 route on Letterboxd, complete with fifteen unranked honorable mentions (#51-65) and one (1) obligatory auteur TV series I defiantly (read: sarcastically) claim “a film.” The top ten, like the full list, is all over the place, from a fictional gastro-intestinal sound collective in Hungary to an investigation into the vile, systemic militarization of US police in the 1960s to an Iranian family mysteriously on the road to the real-time reclamation of Black history. I made separate lists for the top 25 documentaries, top 25 international films, and my favorite new-to-me non-2022 watches of the year. (Bonus: an obligatory mock top ten of all-time for the Sight & Sound poll.)

For the sake of this top ten list, the imminent list of honorable mentions (#11-30) includes: Great Freedom, A Night of Knowing Nothing, Navalny, Till, Athena, Decision to Leave, Lux Æterna, Nope, The Eternal Daughter, Murina, The Fabelmans, No Bears, Beba, Saloum, Sundown, Return to Seoul, Moonage Daydream, The Cathedral, Both Sides of the Blade, and Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood.

Finally, the five worst movies I saw this year––without any justifying commentary, because they aren’t worth the breath or phalangeal stress it would take to detail their cinematic crimes––were: Call of God, Moonfall, Selena Gomez: My Mind & Me, Dreamin’ Wild, and Thor: Love and Thunder.

Now, without further ado, the top ten.

10. Flux Gourmet (Peter Strickland)

Believe it or not, somebody found out how to use Asa Butterfield. Continuing Petey Strick’s (as he’s affectionately known by me and my friends) career-trend of previously unimagined what-the-fuckery, Flux Gourmet––perhaps the most bizarre character Venn diagram you’ll ever encounter––feels more like something you’d find on “The Eric Andre Show” than in the Berlin lineup. The commonalities? Sonic experimentalism, culinary performance (this does not mean cooking), messiness, obstinance, frustration, and farting. Strickland is an international treasure, a writer-director who refuses to turn in a stale assignment, much less a film that in any way resembles the thousands that came before it. Within, you’ll find the new cinematic height for the morning ritual (soundtracked so well in slo-mo to the same song that it brings the In the Mood for Love theme to mind), salacious after-party orgies shot in extreme closeup, obnoxious terrorist phone calls, “epicurean toxicity,” sad turtle stuff, an alt ten commandments, a new finger game, long lenses, low f-stops, celiac catharsis, and the most absurdly sincere characters. Their unflinching commitment to the gravity and absurdity of it all gives the film a nonstop comedic edge, making it the funniest movie of the year. (Strickland never underestimates the power of laughing at one’s self.) They set up pads and wires between blenders and mics and pedals and pots and pans and other non-instrumental instruments to work out their communal and sonic dissonance via alimentary play. And though it just causes more bitterness between them, they press on in misery. When you break it down, it’s a funny, fucked up, feuding band movie about people who kind of hate each other (but need each other more) and the gassy Hungarian writer stuck torturously in their midst.

9. Aftersun (Charlotte Wells)

Every shot is essential. Every feeling lasts. It’s been seven months since I unassumingly saw Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun at an unspeakable morning hour in the Director’s Fortnight sidebar at Cannes, and I still can’t stop thinking about that polaroid shot. Just after a photo is taken, the camera cuts to a long-held still of the polaroid image slowly apparating. It’s the shot I’ve dwelt on most this year and not just because of its clever take on duration. In narrative context, it delivers a seminal moment, but in its assured simplicity and affecting achievability, it’s the most refreshing kind of reminder that anyone––even debut writer-directors working on a microbudget––can find inventive visual forms and shoot a striking film if they’re thoughtful and willing to embrace creative limitations. DP Gregory Oke has only shot two features, but you’d think he’s shot a thousand. The imagery in Aftersun is as bare and economical as the best cinematography can be. There’s a bold, unerring confidence in Oke’s chaste shot design: compositions are sumptuous and spare; yet the frame always feels full, the colors affecting. The phantom-like emphasis on loose thematic connections across shots sets a contemplative tone and draws the viewer into a depth of feeling that can only be evoked by work this brilliant. It features Internet boyfriend Paul Mescal alongside the most charming newcomer this side of the Rio Grande, 12-year-old Frankie Corio. The two have an unbeatable father-daughter chemistry––one that’s already landed them co-nominations for some awards––that lends the tender, quiet story the emotional weight of the world to play with. When it’s sweet, the connective tissue felt between them is an all-encompassing bliss. But when it hurts…goddammit it hurts.

8. Hit the Road (Panah Panahi)

“Where are you taking my child?” The unnerving mystery at the heart of Iranian writer-director Panah Panahi’s (son of legend Jafar Panahi) debut hovers beneath the surface of an otherwise quirky, chaotic, gut-busting family road trip drama. The crew: a tender, worried mom, a loveable oaf of an injured dad, the most adorable 6-year-old little brother, and a near-silent older brother behind the wheel. Exactly what is on everyone’s mind remains hidden in the fog-choked mountainside abyss of their endpoint until the final moments. But it comes out along the way in a steep range of emotion, as our most pressure-cooked feelings often do: a comical, life-ruining conversation about Lance Armstrong, plants nurturing people in the midst of mourning, deep existential uncertainty. Balancing cocaine-quick family dialogue with long, pregnant pauses of anticipatory stillness with unforgettable needle drops (as road trip movies are contractually obligated to have) and everything in between, Panahi oscillates between devastation and glee with poise, proving himself a filmmaker worth looking out for. Sometimes nepotism is a good thing.

7. Descendant (Margaret Brown)

A rich, awe-inspiring archival tapestry woven with buried history, neglected memory, incredible cinematography, Zora Neale Hurston, and generational communal resistance, Margaret Brown’s Descendant is a clear look at how Black stories have been and are still slyly and systematically suffocated in the US. We follow the Alabama-based descendants of the Clotilde––the last ship known to have successfully brought (110) kidnapped African slaves back to the US in 1860––as they continue their 160-year effort to get their known oral history affirmed and recognized in an official historical capacity. It’s a powerful depiction of unwavering reclamation in modern times, the way capitalism adapts to allow the same kind of power mongers to exploit it, the many attitudes that surround shameful historical revelation, and the complexity in mass reparations no matter how deserved they are. Few films will ever uncover history before your eyes so literally and with such captivating and compelling consequences.

6. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (Laura Poitras)

I went long on Laura Poitras and Nan Goldin’s collaborative documentary once this year. I’d already seen it once at Venice, where it ranked among my favorites yet fell a bit short of my unfounded but bolstered expectation for a bomb of an investigative reveal into the Sacklers. Alas, it’s much richer than a takedown. The Sacklers are satisfingly slammed and devastatingly still off the hook, sure, but in Goldin’s sage, candid reflections on her life, work, community, and activism, it’s actually an existential upper––the kind of the film that offers strength to persevere through the worst of life and significant evidence that things will get better. So, I send you to my NYFF review above for more detail on what makes it so great. I wrote on it after my second viewing. I brought a group of my closest friends with me and hit like a ton of bricks I still haven’t worn off. It’s a film that can both whop you on first visit and require a full second watch’s worth of attention to start to swallow what it’s all about beyond the photographer’s fascinating, painful art life.

5. Elvis (Baz Luhrmann)

Looking in the rearview mirror, if I could change one review I wrote this year––though it was honest when I wrote it––it would be Elvis. In short, it was a movie I needed to sit with before I could appreciate. So, I want to do a fun thing and recontextualize the C+ Cannes review I wrote via an abridged and redacted version. Once a C+, now an A, let’s say.

“Elvis is kind of like if you gave a thousand people disparate creative projects with a vaguely similar subject and thematic throughline—let’s say Elvis and excess—and instead of trying to direct them into a legible whole throughout, you haphazardly stitched them together at the end unedited with the goal of achieving only three things: a breakneck pace capable of inducing nausea, spectacular design, and an infinite, impenetrable sense of stardom. Whether you love it or hate it (both factions will be loud), there’s no denying the originality.

Costume designer, production designer, and producer Catherine Martin deserves just as much credit for the past 26 years of her husband’s films—defined by her inventive baroque stylings—and Elvis is her most phenomenal work yet. The only person to collect Production Design and Costume Design Oscars for the same movie in the same year, Martin is absolutely essential. In earnest, Luhrmann’s screenwriting is the main problem, and that’s exacerbated here.

It comes across as a joke—the movie called Elvis about Elvis follows… Elvis’s manager? It seems especially silly when you have Austin Butler playing Elvis. Butler—who got the role after Denzel Washington cold-called Luhrmann and insisted Butler (who’d he’d just worked with on a play) was the best guy for the part—is an absolute knockout, an Elvis to end all Elvis’s, and the biggest reason, tied with Martin’s design, to watch. Otherwise there’s a black hole of fluff where profound storytelling could be, a giant, blinking marquee arrow pointing to Butler and Martin’s work.

Last but certainly not least: the music. There’s plenty of Elvis and non-Elvis, though not much, if any, traditional Elvis. The closest thing to that is a relatively true (and brief) Kacey Musgraves cover of “Can’t Help Falling in Love” that plays for no more than a minute. Otherwise Elliott Wheeler’s music is gaudy and contemporary—incorporating rap, hip-hop, house beats, and pop sounds, as in The Great Gatsby. But it’s so damn inventive and widespread across Elvis’s catalog that you can’t help but admire it.

If Elvis ultimately isn’t about the music or the story, the former outshines the latter. Luhrmann films (or should we call them Luhrmann-Martin films?) are about aesthetics. Elvis is a jerky, crick-in-the-nick rollercoaster ride that apparently wants us to know how bad it felt to be on one of his legendary benders. But Stylistically it’s impeccable––the cinematic Elvisification of everything, from 1950s Memphis to trippy cinematography to B.B. King to Kodi Smit-McPhee’s character from The Power of the Dog.

It’s tough to watch a movie like Elvis and totally dismiss it, no matter how much of a trainwreck it might seem. Name a department that isn’t the Tom Hanks department and there’s plenty of creative work worth praising.”

There, see…the review was glowing…

4. Riotsville, U.S.A. (Sierra Pettengill)

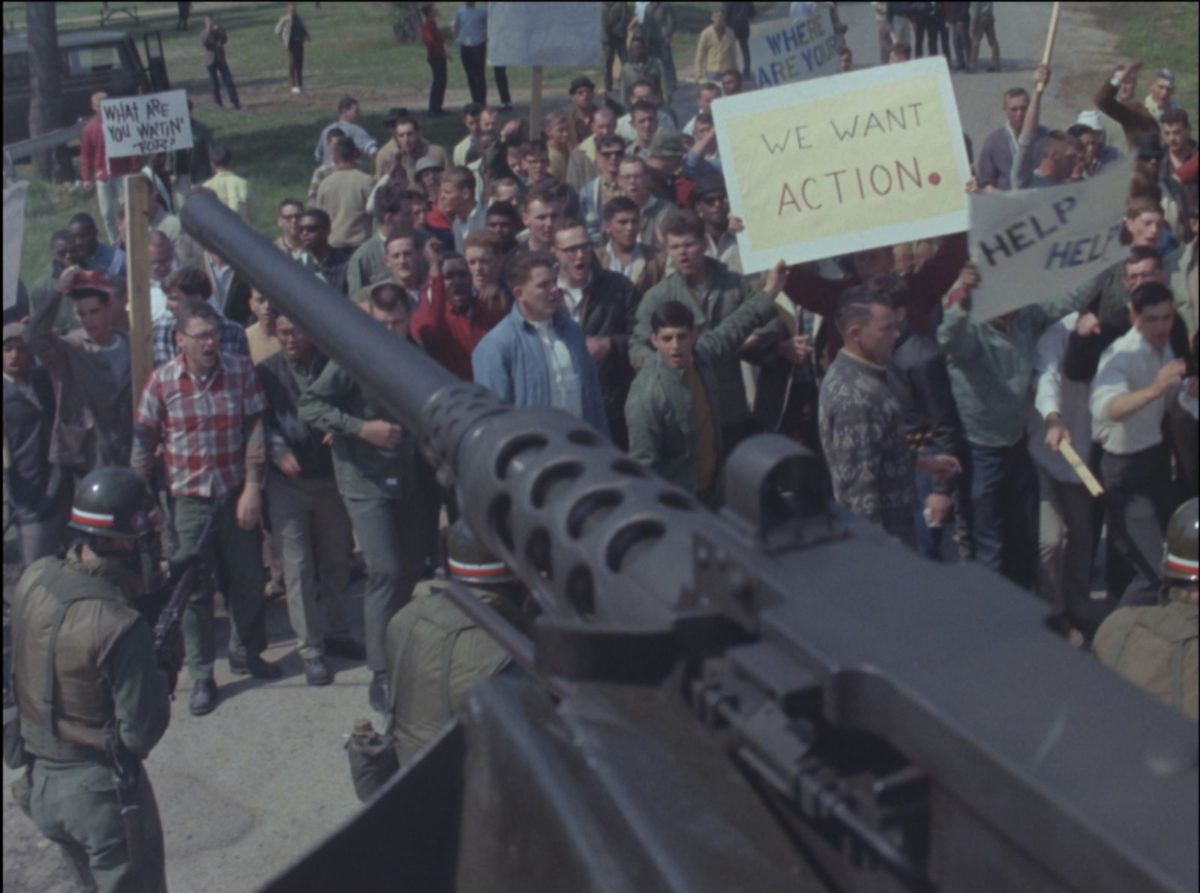

As we get further from the 60s, more previously classified stories come to light, more insight into the mechanics of our country becomes available, and history becomes a bit clearer. In this case, as in many, it’s an ugly history to have to stare down, the norm when it comes to protest or Black life in America. How were US police forces so equipped to crush protest with an iron fist? How did they all know the same methods? When did they train? Where? Why were military and political officials so concerned about the rise of the civil rights movement in the first place? How was something this inhumane, this blatantly anti-equality ever funded, much less at a multi-billion pricepoint and with the signatures of our nation’s leaders? The answers are found in Riotsville, U.S.A.

Pettengill’s abrasion of the military’s response to organic civil disorder rescucitates stories lost in the fog of collective memory. Details about the non-partisan Kerner Comission and its once-famous Riot Report – which found that “vast efforts [were] needed at once” to achieve a great leveling of society in the name of quality and “national unity” – are woven throughout, as is the ghost of the PBL, the PBS that was too liberal for state-sanctioned operations and thus defunded and taken off the air. Pettengill makes sure to capture the historical KKK connections behind so much of the military’s personnel, facilities, and philosophies as they come into play. She treats peripheral and adjacent stories like threads of essential side quests that form the final complex tapestry (a la Theo Anthony, who was thanked in the credits), leading us into riveting subplots about the national fear stoked over snipers when the only real threat was cops killing innocent people they misidentified in windows, or the nasty event that unfolded in a Miami Beach suburb during the 1969 RNC that we never hear about, in which an innocent Black community was swarmed, infested, and terrorized by the National Guard under the entirely unveiled guise (e.g. tanks firing tear gas into houses on main) of national security.

Riotsville, U.S.A. is my yearly “damn the American Military Industrial Complex” pick. I always think I’ll go a year without one. But it seems the sheer number of secrets to share has landed us in a perpetual waterfall of shameful revelation about American history behind closed doors that will continue to churn out shocking behind-the-scenes docs. And Pettengill’s is one for the books, an impeccably scored, oft-avant-garde investigation (e.g., extreme closeups on the slow-motion morphing of jerky pixels with a blocky, sharply pitched, arpeggiating soundscape to portray the 1969 Chicago DNC opposed to plain footage) into a buried element of an infamous chapter in American history.

3. Ahed’s Knee (Nadav Lapid)

It happens every year. A handful of impeccable, seemingly unforgettable films that debuted at festivals over a year ago get lost in the arbitrary discrepancies of year-end list chaos. Some have brief, meager theatrical runs at best. Others are deemed too challenging, slow, inaccessible, or button-pushing and meet the terrible fate of being quietly jettisoned into the Bad Movie Beyond of a streamer’s search results. This year, it happened to one of the year’s best: writer and director Nadav Lapid’s Ahed’s Knee, an Israeli film that goes straight for the Israeli people’s jugular, right after it’s done ripping out the Israeli government’s rib cage. Lapid’s visceral, vitriolic firecracker about an Israeli director returning to a small desert town in his home country for a screening is as incendiary as it gets. You can hear the brilliantly long-winded dialogue coming from Lapid’s mouth as much Avshalom Pollak’s, the explosive lead tortured by what he considers a debased collective morality and total disregard for truth and ontological ethics. But it’s Lapid’s direction that deserves the most praise––an electrifying feast of style, technique, and imagination that draws out the unspokens (of which there are few) of the textured metanarrative and immerses you in every moment with an earned imminence. Everyone has their pet favorites of the year, but don’t confuse Ahed’s Knee for niche pet praise. If it had had a more public distribution journey, it might be one of the most talked about films of the year. Don’t miss it. And for commentary, here’s my conversation with Lapid from earlier in the year.

2. Fire of Love (Sara Dosa)

I briefly reached nirvana in 2018 watching Morgan Neville’s Won’t You Be My Neighbor? For reasons not worth getting into, I wouldn’t call it one of my favorite recent films, but I’d call what it imbues me with one of my favorite feelings. It also confirmed for me, like it did for many, that Mr. Rogers was one of my favorite people. And it taught me that it had very little to do with his actual creative output and everything to do with his philosophy. To capture that lived philosophy––the purity and goodness of Mr. Rogers, the mechanics of his mind, the essence of his soul, the contagious love, compassion, and openness in him––almost tangibly is nothing short of directorial genius. I tell you this because Fire of Love is the only film that’s made me feel the same way since, courtesy of director Sara Dosa. It’s more like a drug than a movie, presenting the viewer with trippy, gorgeous, and unbelievably captured visuals of molten, grainy volcanic film footage while intoxicating them with a delightfully overwhelming sense of hope, love, quirk, vigor, ambition, confidence, and self-worth. The source, however, isn’t the volcanoes. It’s the Kraffts. Katia and Maurice Krafft are, like Mr. Rogers, among the most strange, strong, open, wonderful, generous, creative, intelligent, diligent, and explosively positive forces in human history (so much so that we can’t rule out extraterrestrials in disguise). The late French volcanologists are like eccentric lovers ripped out of a Wes Anderson movie, too silly to seem believable if it were fiction. And like with Rogers, it’s their philosophy that finds its way into your bones: their unwavering, field-leading passion to chase, study, document, film, and educate the public on (the dangers of) volcanoes at constant career risk of death by fresh neon lava, a risk they unquestionably embraced in the name of fully lived lives as much as scientific discovery. They ultimately, tragically died from a volcano eruption in Japan in 1991 in their mid-to-late 40s but not without leaving behind a vital, invaluable contagion of spirit, a raison d’etre, a world-changing legacy in cinematic perpetuity. Life isn’t worth living without the risk of experiencing it.

1. EO (Jerzy Skolimowski)

Descending into a thick, blood red forest cast in pitch-black shadow, the camera races along the surface of a creek winding through the woods for a long while before it finds itself in the open sky facing down a wind turbine. Still charging ahead, the camera suddenly begins to barrel roll at the same speed of the turbine, flipping us over and over again like we’ve been tossed into a washing machine. It’s only one of the seemingly endless number of visual aesthetics and expressive techniques employed in Michael Dymek’s prismatic work on EO, Jerzy Skolimowski’s Polish Au Hasard Balthazar remake for the modern existential state, the 21st-century human condition. A film that arrests your empathy through the erratic journey of a wandering donkey, EO is a spectacle of impressionist cinematography that says more about being human than perhaps any 2022 movie with a human at the center, in large part due to Dymek’s range, a rollercoaster of lenses, movements, and styles as breakneck and unpredictable as life itself. From a crisp black and white music video to a hazy, Lubezki-esque dream state with bleary edges to a lens seemingly dropped into a warped glass of water, the style characterizes and emotes on behalf of the mute protagonist better than most dialogue, reminding us what the most thoughtful cinematography can achieve in character and theme. Leave it to an octogenarian legend to inspire a burgeoning 32-year-old’s best work.

Stepping out into the sunlight of the French Riviera in mid-may Cannes after an EO afternoon was a delight, a mini awakening of sorts. Emotionally, I’d fallen so far over the brisk 86 minutes of enveloping experimental jackassery that I needed a breath like I needed to remember what it was to have autonomy. But it was the best kind of overwhelming, the kind born from total immersion. And it was no less radiant in New York the second time around (where I wrote much more on it). Or, by that point, at my house the third time. I was EO-pilled, savoring every frame like it could be the last time I see it. As a relatively dialogue-free film that follows a Polish donkey, it might seem like unapproachable arthouse, but EO is as engaging and galvanizing as the next masterpiece.