Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2021, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

Music docs, Memoria, and more music docs: welcome to my top ten. There are some non-music-docs, but only seven. It was almost six. And in a rare moment of clarity I exercised restraint. I’ll probably regret it. Themes are disparate between the rest. From unseen masterwork to global phenomenon, Chile to Romania, nautical myth to coming of age in the ’70s––they run the gamut.

To the point of showing there’s no such thing as a “bad year” in cinema, my list of honorable mentions is insufferable. Barely edging out the top ten is The Power of the Dog, The Worst Person in the World, The Velvet Underground, and Drive My Car, any of them a likely 9 or 10 spot were I writing this on a different day.

In the next tier is The Souvenir Part II, The French Dispatch, Titane, The Tragedy of Macbeth, The Disciple, Benedetta, Faya Dayi, C’mon C’mon, Red Rocket, All Light, Everywhere, and Parallel Mothers. I’ll stop listing, but you can find the full top 25 here and find the honorable mentions here. And, of course, there’s always missed connections, The Inheritance, Il Buco, and The Tale of King Crab, to name a few for me this year. Alright, without further ado: the first music doc.

10. The Sparks Brothers (Edgar Wright)

Watching The Sparks Brothers is kind of like taking the Limitless drug. An endless pool of inspiration that’s plug-and-play ready for your next deadening creative roadblock, this documentary rips and reels through the historic musical career of the brothers known as Sparks. Or should I say not known? That’s the premise of Edgar Wright’s passion project: “The Greatest Band You’ve Never Heard Of.” The other tagline––“Your Favorite Band’s Favorite Band”––gets the point across in a different way. They’re not just a great band; they’re a source of creativity, one of the bands that makes the best bands great. Why? They constantly redefined themselves.

Ron and Russel Mael––a pair of eternally fascinating subjects minted for Wright’s colorful, kinetic filmmaking style––are those rare artists who do it all and, perhaps more importantly, never look back. Sparks’ 50-year career is a gobsmacking loop of innovation, imagination, and reinvention that infuses a confidence to create, an assuredness that the potential for great artistry lies within everyone, and a security in knowing that failures are not fatal wounds or inhibitors of future creation. The brothers take us album-by-album through their discography, each addition seemingly written by a different band. Seeing them do everything makes you feel like you can do anything. It’s intoxicating.

9. Days (Tsai Ming-liang)

There’s no way I can measure what Days has meant to me over the course of the pandemic. It would be in the top few in that regard. I saw it at the virtual New York Film Festival (in my living room), a dour way to experience an innately social event, but it was one of the few that might’ve played better in that environment. It came at a time when I (like everyone else) desperately needed some form of respite. All my normal tricks were wearing thin, and it burst in like a freight train of transcendent calm in my life.

Tsai Ming-liang and Lee Kang-sheng, one of the most prolific director-actor duos of all-time, are reaching uninhabited levels of familiarity with their work. The way the lives of the two have bled over time into Lee’s character has led them to remarkably transparent places. Here, Lee’s real-world pain takes center stage, and we watch him drift silently through treatments and physical encounters. He sits or lays unflinchingly for minutes at a time while the compositions and sound design work wonders and busy the mind.

As there is almost no dialogue, so much of it becomes reflective. I can’t imagine we’re intended to watch Lee’s statue every second. Days is a cavernous story. The mind naturally wanders in a film like that. It’s an aspect of Eastern cinema / entertainment that doesn’t always translate to Western audiences. But it’s basically film therapy. One minute he’s washing vegetables; the next you’ve accidentally mentally worked your way through an internal conflict you were dreading giving your emotional attention. It feels great and it’s still the same shot. Who knows what else you’ll get up to.

On the flip side, some scenes are so carnal and wonderful you won’t forget them for a long time. You’ll feel them long after they’ve played. They can create a parallel urge for peaceable solitude and erotic connection, a therapy of touch that nourishes the spirit like the one Lee finds unexpectedly in a male sex worker. It’s a pure, human experience—simple, essential, and delicious in the same way one might describe water.

8. Licorice Pizza (Paul Thomas Anderson)

I can’t name a favorite film, but I can name a favorite filmmaker. I’ll give you a hint: it’s Paul Thomas Anderson. The prospect of a new PTA film is always debilitatingly exciting, and Licorice Pizza was no exception. At the same time, I’ve only ever loved one PTA film on first watch, so I always try to keep my expectations at bay. Of course it doesn’t work and the cycle repeats. But Licorice Pizza was different. Two watches deep, I’ve loved it both times––the gorgeously degraded characteristic of the imagery, the lovable (first-time-actor) leads, the commentary on being lost in your 20s, the hangout vibe that runs through it all, that spotlight in front of the store, nearly every conversation. PTA knows exactly what he’s doing and he gives his fellow creatives space and creative motivation to do their best work.

There’s a strongly felt ease and a particular magic to the connection between Gary (Cooper Hoffman) and Alana (Alana Haim), the kind that exists both innocently and deeply in the strangest of flirtatious friendships. Someday I think I’ll be knocked off my feet by it, but that was the only glowing aspect I experienced at a distance. The movie arrived when I was, frankly, embarrassed at how much I saw aspects of my own life in the boyish excitement of a romantically enthralled teenage entrepreneur. But I know this PTA will transform for me like the rest of them. And regardless, it’s still one of the best movies of the year. Here’s my conversation with DP Michael Bauman.

7. Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (Radu Jude)

There isn’t much I can tell you about Radu Jude’s boundary-breaking spectacle that won’t surprise you. To start, it’s about a Romanian grade school teacher (an amazing, often masked Katia Pascariu) put on trial by her students’ angriest parents after a raunchy sex tape with her husband leaks and the students see it. Second, it begins with that sex tape that is long and graphic enough to weed out a third of any audience before the story actually gets going. Third, it has multiple endings. None are the actual ending. Fourth, one of the three acts is composed entirely of out-of-context visual metaphors that range from angry to darkly comedic to heartbreaking to visually stimulating.

The two acts surrounding the visual metaphors follow the teacher, Emi. The first act traces her voyeuristically as she goes about her day. There’s nothing much to report narratively but the camerawork is so good, drifting from monument to building to sign to whatever else surrounds Emi, always making a point to move steadily, incrementally, curiously, capturing the bustling wake of life between her and the camera. The third act is an explosive finale. As the parents express their concerns and Emi defends her right to innocently film herself having sex with her husband, the bigotted nature of the parents begins to spill over, leading to a chaotic, at times satirical, bout that means to make a point about the traditions that keep society from evolving for the better.

6. Ema (Pablo Larraín)

It’s frustrating, but it’s true that every year sees at least a handful of films get lost in distribution limbo, eventually released but largely disregarded, buzz from a distant festival having faded into obscurity long ago. As a result, it gets left off year-end lists it could theoretically be eligible for two years in a row, one year because it technically hasn’t been released, the next year because, by the time it comes, it’s been around too long. Critics find it disingenuous or simply strange to include. Pablo Larraín’s Ema––the only remarkable Larraín film released this year, despite the other showing greater initial promise––got it even worse.

Stretched across three years (2019-2021), the spicy experimental dance thriller about adoption, domestication, and carnal desire premiered back-to-back with Joker at Venice in August 2019. There was a ten-minute break between screenings. Joker would go on to be the most popular picture of 2019 globally. Ema left the festival still on the market, the pandemic took hold, and the film wouldn’t see American theaters until its brief, limited release in August 2021. But botched distribution isn’t the reason to see the movie. Everything about Ema is worth your while: the winding maze of a story, the seductive philosophizing, the choreographed reggaeton flamethrowing, the fiery Mariana Di Girólamo and Gael García Bernal performances, the hypnotizing Nicolas Jaar score, the Chilean mountainside, et al. It’s rarified air.

5. Dune (Denis Villeneuve)

Dune is more philosophy than anything. From a pop-culture-radicalizing book to a monumental theological sci-fi worldbuilding series to an unrealized bizarro epic in Jodorowsky’s phantom version to a Lynch disasterpiece and now to Denis Villeneuve. He took on a tormented history in the form of a supposedly untellable story and just plainly knocked it out of the park. There’s no way you can fit all of Frank Herbert’s world into the frame, and Villeneuve and co. understand that. Being in Villeneuve’s Dune is like walking among future giants in inexplicably ancient civilizations that are also 8,000 years in the future. Everything is too big to see and the effect is immersive.

The Hans Zimmer score, Greig Fraser cinematography, and Patrice Vermette production design are collectively entrancing. At the center is the fascinating complexity of what’s unfolding––a resource-rich desert planet at the crux of intergalactic warfare, a scheming political witch coven, planted religions, and a faux-Messiah that painfully embraces a new way of life. Ferguson is terrific as Lady Jessica. Chalamet gives an expected yet perfect Paul. (It will never not be funny that all of this is about a guy named Paul.) Stephen McKinley Henderson stands out in a strong, stacked supporting cast.

There’s so much about experiencing a movie that comes down to an untraceable flow and feel, something great filmmakers just have a sense for. It’s one of Villeneueve’s strongest qualities. There are so many technical elements to point out (e.g. the way they paint with iridescent flares on a canvas of monochromatic sand, or use sound design to make us feel the fear being expressed in a scene), but it all boils down to the filmmakers’ ability to make two and a half hours feel like ninety minutes. The experience is like witnessing the flow of reality in real time and somehow, in the process, becoming newly aware of its wavelike patterns in your own life.

4. Undine (Christian Petzold)

Tied with the Dune for the movie I watched the most this year at six, Undine is an absolute treasure to me. Writer-director Christian Petzold is a veteran of his craft, one with an impeccable sense for weaving together loosely connected motifs and the motion of the camera and the natural progression of the narrative to make something that feels so whole, so unified. As if that isn’t enough, he always adds the perfect touch of humor (here in the form of “Staying Alive”), keeps us guessing about ten things at once, and ends with a bang. Not to mention he tells new stories—which makes Undine, a popular Germanic myth, an interesting move.

But Petzold finds a way to make a version of this story so different it’s almost unrecognizable. He creates an ideological whirlpool of political history, architectural philosophy, and romantic myth, and drops a modern love story in the center to see what happens. It’s one of those movies that plays over and over in my head like a daydream. It’s beautiful, joyous, earnest, but there’s also something off that I can’t quite put my finger on. I see flashes of the leads––Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski, who are immaculate in their respective roles, but even more so in their chemistry––craning their necks into each other at the train station, rolling around in a fit of romance over slaughtered sheets, wrapped in a comforter on the balcony. Then, I remember the deep blue of the water, the feelings of loneliness and loss, the reality of the myth. And it makes it that much better. I interviewed Petzold and Beer earlier last year.

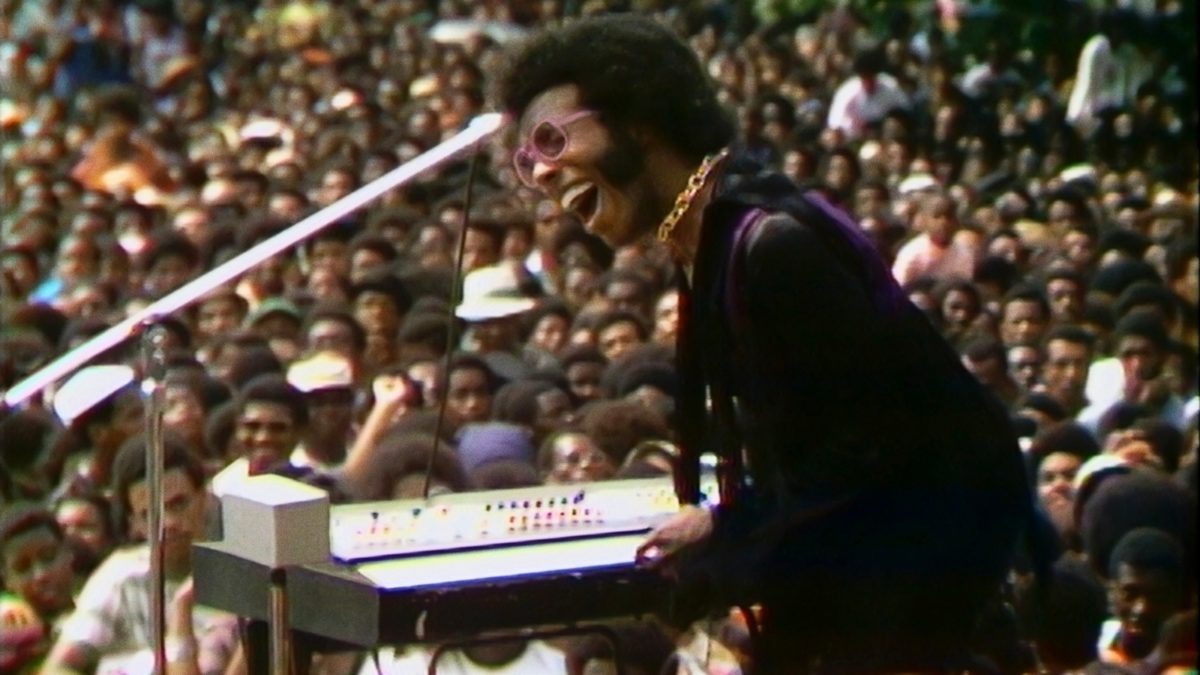

3. Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson)

Questlove’s first jawn is as easy a sell as The Beatles: Get Back. The question is virtually the same: do you want to watch unseen footage of an iconic moment in music history in 1969? Even more so: from some of the best musicians on the planet in their prime? Nina Simone, B.B. King, Sly and the Family Stone, Mahalia Jackson, 19-year-old Stevie Wonder—just a handful of the acts who headlined the Harlem Cultural Festival that year, and it’s all on glorious film, shelved in a basement somewhere because networks were afraid to televise it at the time. When you see the revolutionary energy Simone inspires in the crowd, you see why it scared powerful people. The event would be coined “Black Woodstock” and live on in rare photographs and oral history until Questlove turned it into an electric concert-film experience via Summer of Soul.

With all the firsthand talking heads, it’s so much more than that, too. Among many things, the documentary is a re-canonization of Black memory, a defiant film that refuses to let Black history remain unseen or unheard. The artists involved add layers of nuance to the moment, going into detail about how the performances affected their lives or how their music played into pop culture at the time. The film blends the concert footage and the interviews with other archival footage to always be better building out the wild moment in history that 1969 was. If you can make it through the opening five minutes without cheering / crying / passing out, you should check your pulse. The blend of socio-cultural musings, setting the historical stage, and a show-stopping Wonder makes for probably the best sequence in a movie all year. Read my essay on it over at The Quietus.

1. Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Tied for #1, Memoria and The Beatles: Get Back are both landmark achievements in their own right. Utterly dissimilar, they are testaments to the way different expressions within a medium can be equally profound. Where Get Back delivers unseen footage of an essential moment in history, Memoria delivers the sonic history of an unseen essence. That essence is twofold. On one hand, it’s the mysterious interior boom in Jessica (Tilda Swinton), a Scottish botanist in the Colombian jungle who spends the film trying to find out where the sound is coming from and why no one else hears it. On the other hand, that essence is the subtle socio-political ripple at the film’s core, a thematic throughline that points to the historical oppression faced by the Colombian people and evokes the pain in their trauma in a singular fashion.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s first film outside of Thailand is a deeply felt existential experience, a still, humming meditation on aural and visual disease, a movie where it seems like nothing is happening until you realize what’s been happening the whole time. It’s restful, exquisitely framed, and grounded in one of Swinton’s best performances. It is as rare a gift as unseen historical footage. I’ll leave it there, but if your interest is piqued, there’s more detail in my conversation with Apichatpong.

Unfortunately for casual moviegoers, Memoria won’t be available anytime soon. But there’s a fun (trying to be positive, I guess?) challenge in trying to see it, as it marks the first film to go on eternal tour, or so they say. According to the Memoria team, the film will never get a wide release, come to streaming, or be available to purchase. Instead, it will tour the world, only ever playing on one screen in one movie theater in one city at a time. Only a matter of minutes before I drop everything to be a traveling groupie.

1. The Beatles: Get Back (Peter Jackson)

I’m still pinching myself. I have been since Thanksgiving. Watch, pinch, cry, rewatch, pick up jaw, cry, pinch harder, repeat tomorrow. It still hurts, thank God. But I still can’t believe it: eight hours unfiltered with the Beatles. Moreover, in 1969, while writing and recording Let It Be. Every second is absolute magic, a clear window into one of the most significant moments in history. It’s the music equivalent of watching Picasso, Dali, and Rivera paint and talk about it in 1920s Paris. But better because it’s the Beatles, who are, after all, the only entity in any creative medium that can definitively be named Most Beloved.

When Peter Jackson said his 3-part documentary would shift the way we see the Beatles at the end of their career, he made a grave understatement. It’s changed the way we understand them entirely – as songwriters, best friends, artists, and people struggling through life like us. It’s remarkable. For one, the music of it all: watching them jam, witnessing Paul come up with “Get Back” in a moment of frustration, hearing all the covers they play, or noticing the way they instinctually, almost flippantly, write lyrics. To see the balance they strike between discussing the direction of a song and feeling it out in sessions. And the fact that it’s these songs makes it even wilder. But there’s so much outside of the music, too.

We hear bugged conversations between John and Paul about the most intimate of topics––who’s the bossiest among them, why George wants to leave, where Paul’s ambitions are headed, how the Beatles should or shouldn’t continue. It’s inane to see how clearly they understood themselves in the context of their fame, yet how impossible it is for them to communicate at times. They predict all the things that will be said about their break up, and, even more impressively, shrug it all off to focus on each other, showing how deeply they still care. We see how playful they were about everything. They’re always having a drink or smoking a joint. They crack jokes religiously, often about themselves. We see them in the banal, too, which is just as fascinating. We have breakfast with them as they talk about what they watched last night and chill with them in the studio with their families. We understand anew that great art can come from anyone because we see the ways they’re like us: George feels dejected by his friends; John is always complaining about not getting enough sleep for reasons totally up to him; Paul is in a perpetual state of work-induced anxiety; Ringo just loves watching the other three play. We see them in new ways, and they’re impossible to look away from.