If the found-footage concept relies on the belief that hand-held images will instantly signal reality, then it’s refreshing that The Dirties has the intelligence to directly pit verisimilitude against fantasy and subjectivity’s place within it.

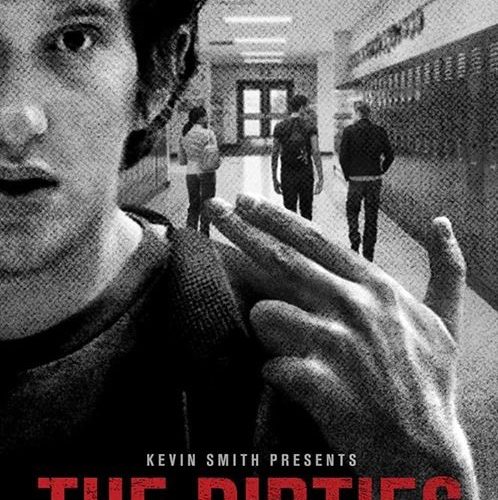

But as for the subject of the found-footage, we find two best friends, but more definitively. high-school outcasts and film buffs, Matt and Owen (the former played by the director Matt Johnson). They decide to document (with the help of an unseen cameraman) the making of their magnum opus, The Dirties, which sees them getting revenge against the school bullies. Their cast and crew consist virtually of themselves and a few accidental participants from their school and outside; itself mirroring the actual film’s use of real people. Though after their disastrous in-class screening, only making them the objects of even further scorn, it’s back to the drawing board as a far more real and deadly project is devised by Matt.

The overall tone of The Dirties truly evidences the intersection of comedy and tragedy; one-liners and movie references hiding pained loneliness and distant realization of one’s own identity. And it’s to the film’s credit that even as its lead mentally unravels, it manages to avoid a certain determinism of darkness; keeping the comedy coming even past the realization of the final plan, though to the point that some in the audience might be realizing that it’s not appropriate to actually laugh any more.

Though the source of much of the laughter seems to be summoned from their own pronounced youth; themselves engaging in the kind of young cinephilia in which of course the main reference points are The Usual Suspects, The Dark Knight and Irreversible and not yet the humanist works of Roberto Rossellini or Yasujiro Ozu. Their natural attraction is to an over-emphasized violence and swagger; one of the biggest laughs from the Fantasia audience being when Matt points out how he managed to copy the exact same movements of Heath Ledger’s The Joker; their own art born purely out of imitation.

Yet in the process of moving from one to the other, playback plays a large part; Final Cut Pro screens seen throughout the film of their cobbled footage in which they’re continually constructing their own visual identities; including much clichéd “cool” imagery of slow-motion bike rides set to pop songs. Matt mentions he wants to set a montage to a Best Coast song, cut to it being watched in the “editing room”; maybe an easy joke, but also at least somewhat earnestly documenting a creative process.

But the further intent of the film lies in their walled-off world; their movie-nerd dungeon adorned with movie posters, DVD’s and VHS tapes, and also an indication of a comfortable middle-class position, and arousing wonder as to what the actual economic situation is within their hometown and school. Though a scene in which they’re humiliated by a bully in the lunchroom because of spilling food on his expensive shirt alludes further to this, it isn’t explored to a greater degree.

As smartly depicted in last year’s 21 Jump Street, high school has gravitated far from the assumed jock/geek social hierarchies, yet to bring the comparison to something a little more similar (another recent Canadian teen film), Blackbird, showed bullying and the aforementioned cliques as still very evident within small-town high schools. It seems in the case of both of these films, all the “culture” belongs to the outcasts, thus they being more naturally alienated by their surroundings and having no choice other than to excessively film and watch.

But that brings up a greater question about The Dirties and potentially its biggest flaws; in trying to notice what’s specifically missing because of its conceit; the parents of Matt and Owen being a prime example (though the former’s real-life mother makes an appearance near the end discussing the definition of insanity), it gives the easy assumption that they were raised by movies and not them; almost asserting a regressive “media makes you violent” quasi-sermonizing. In being able to further understand the world of in and outside the high school, it would also make Matt and Owen’s eventual split over a girl less facile, as well as creating more distance between the former’s ugly misogyny.

Potential for greater social commentary is also seen in a scene near the beginning in which a likely real teacher is being asked of how kids should deal with bullying, to which he gives a predictably glib and unhelpful solution. If to quote 90’s faux-punk nihilists The Offspring riffing on The Who, “the kids aren’t all right,” then will they ever be? Shooting down the “It gets better” mantra only goes so far when the system itself is as well established as their factory-churned catchphrases.

Yet still, to deny the overall accomplishments of The Dirties would be an injustice; Johnson’s debut promises great things to come, being that as he gets older (he convincingly played a high-school student after all) he’ll be even more steps ahead of his young, tortured dreamers.

The Dirties opens on October 4th and one can see the first trailer below.