In a nation of repressed emotions, three young teens find themselves confronting their feelings at what might be their last opportunity to do so. Shy Norimichi (Masaki Suda) can’t stop himself from starring at Nazuna (Suzu Hirose) while his more confident best friend Yûsuke (Mamoru Miyano) admits to wanting to declare his love for her. The boys seek to deflect their obvious infatuations, falling over each other in embarrassment so that the other can win his prize regardless of how the object of their affection feels about either. So when the trio find themselves in the midst of a swimming race, fate decides for them. Norimichi hurts his foot, Yûsuke keeps his stride, and Nazuna’s victor impulsively asks the latter on a date simply because he surfaced first.

This ordeal sets the stage for directors Akiyuki Shimbô and Nobuyuki Takeuchi’s Fireworks, adapted by Hitoshi Ône from Shunji Iwai’s 1993 teleplay. Where a synopsis of the original seems to stop at the romantic drama that inevitably follows, the film takes things through a refracted lens of infinite possibilities all stemming from a bet between Norimichi, Yûsuke, and chums about whether fireworks are round or flat. In order to collectively confirm a winner, the group decides to watch that night’s show from a lighthouse positioned directly next to the explosives’ launch site. Unfortunately for Yûsuke, this celebration was also the target of Nazuna’s invitation. Either to escape peer ridicule or bow out of a nonexistent competition with his friend, he tells Norimichi to take his place.

Here’s where things get interesting. Nazuna has only decided to create this date because she has learned her mother is remarrying and moving them out-of-town. She therefore seeks an escape — packing a suitcase while hoping to cajole a lustful boy into helping. Or is she simply hoping to capture one last memory of a home she may never see again? Or perhaps … it could be anything. This is kind of the point because nobody knows anything but his/her circumstances. Nobody knows what he/she will do in response until faced with that choice. What will Norimichi do when Yûsuke runs away from his plans with Nazuna? What will the two of them do if her parents show up to ruin any chance for connection to occur?

As we soon discover: it doesn’t matter. Because if the wrong choices are made, Norimichi can throw a tiny crystal marble Nazuna found at the beach that morning and make a wish. Time will suddenly start playing in reverse until landing on the spot he wants to change. But it isn’t just a matter of time travel. For some reason characters have completely different motivations too. Whereas the first Yûsuke was awkwardly eager to let Norimichi’s crush succeed, the second Yûsuke is jealous beyond compare. You want to think it’s merely a result of their changing circumstances, but we didn’t go back to the very beginning. Everything that occurred prior to their swimming race theoretically remains intact. So everything Yûsuke does afterwards makes zero sense by comparison.

The one thing that does remain consistent is a creepy, lecherous tone. Not only is Norimichi shown to be a voyeur in relationship to Nazuna’s weirdly sexualized depiction considering the ages involved, but the boys are also constantly talking about sexually harassing their teacher Ms. Miura (Kana Hanazawa). What’s so bad about the latter is the fact that her character is completely meaningless to the work as a whole except for these off-color jokes. She exists to be abused much like Nazuna does to be coveted. While you assume this young girl will be drawn with equal importance and agency as Norimichi since their journey forward is together, the truth proves the opposite. This is Norimichi’s fantasy and she’s sadly just his prize. Actual romance is therefore non-existent.

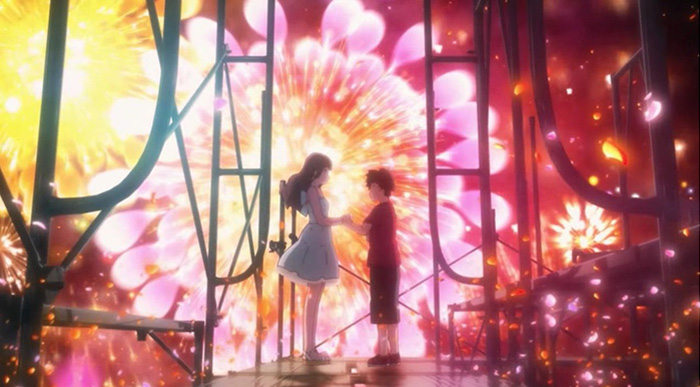

It’s a real shame because the filmmakers have some interesting ideas about parallel timelines being distinguished by the shape of their fireworks. More than that, the marble serving as the catalyst to the film’s high concept scrubbing through time has a dual role mimicking both the appearance of a firework shell and the glass bulb of the lighthouse. Its aesthetic composition becomes the trigger that shifts reality under these kids’ feet until we end up in a world that could very well be taking place within it. And the level of artistic detail in the texture of light, glass, and any object for that matter (trains, home decorating, etc.) is spectacular. Besides the very anime look of the characters themselves, the rest possesses an unparalleled and uncanny photorealism.

So here’s this gorgeous-looking work steeped inside a mythology that literally rips apart the fabric of space and time to deliver a thought-provoking final-frame mystery and I couldn’t enjoy it. Between the salacious vantage Shimbô and company creates by presenting everything through a hormonal teenage boy’s eyes and the stark contrast between realities one and two despite two, three, four, and beyond being identical outside of preplanned actions, it all feels wrong. What should be tender and whimsical feels repetitive and off-putting. And without clear rules to what’s happening, we never get a handle on whether anything exists beyond delusions manufactured from Norimichi’s regrets. There’s a major problem when your message seems to be “Love doesn’t need reciprocation when you can just pretend you have it anyway.”

Fireworks is now playing the Fantasia International Film Festival.