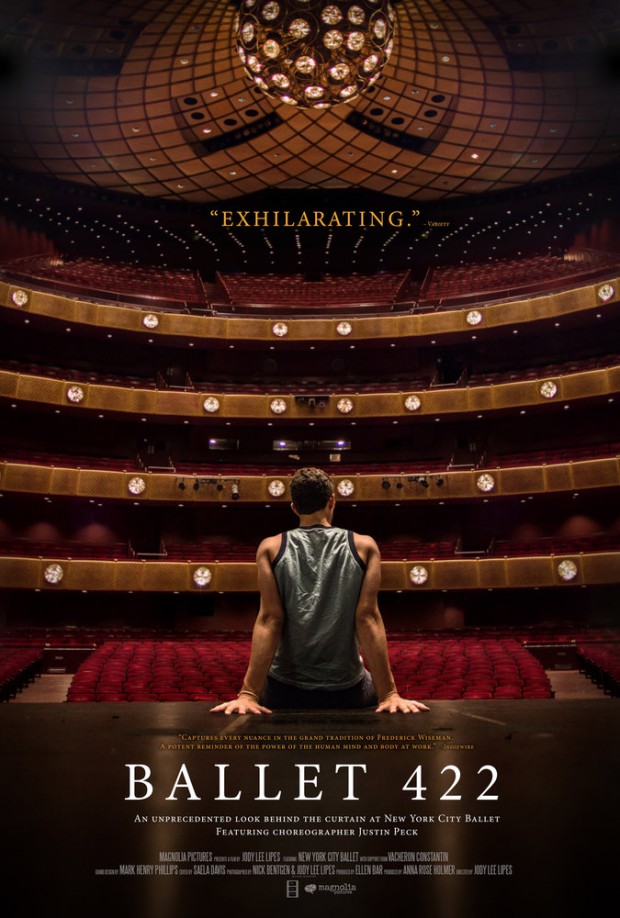

There is a unique creative purity that filmmaker Jody Lee Lipes is able to capture in his enthralling documentary Ballet 422. The cinematographer/director is no stranger to filming bodies in motion, having lensed the magnificent dance film NY Export: Opus Jazz which showcased talented dancers performing through New York City.

In his latest effort, the Martha Marcy May Marlene cinematographer takes a more intimate approach by following around ballet prodigy Justin Peck as he prepares, conceives and choreographs an original concept for the prestigious New York City Ballet. It’s a truly fascinating film for both the artist in front of the camera and the one behind it, as they both examine the concept of artistic inception. I was fortunate enough to sit down with Jody and discuss his blossoming career, his verité style and his advice for future filmmakers.

The Film Stage: How did you find Justin and become involved in this project and did it have anything to do with your previous film NY Export: Opus Jazz?

Jody Lee Lipes: It did. I got involved with Justin because Ellen Bar, who’s one of the producers on this film, was moderating a panel at the Guggenheim that Justin was on. Part of that panel was Justin having one of the dancers go through a ballet that he was working on at the time. Just watching that process and how we he worked with the dancer after she went through it once and he corrected her, it was so fascinating to me. He just seemed like he would be a great subject. One of the things that really interests me is focus, like extreme focus and I saw that on stage that day. As soon as that was over I was like huh, maybe we could do a film about this. Ellen Bar knows Justin really well, they were in the same company for a long time. So she helped us find the opportunity to get in there and to put the whole film together and make it happen.

What did it take to earn Justin’s trust and how did you get him to be so earnest and candid in front of the camera?

Justin was really open about this whole process and enthusiastic. He never said no. I don’t think he even totally realized that it was going to be what it was going to be. It’s not like we hid that from him but I think he just sort of thought like, ok they’re going to shoot some stuff, that’s cool, I’m happy to have them document this. But at first we didn’t know it was going to be a feature like at the very beginning. So he was very, very open about it.

So it was kind of amorphous at the beginning?

Initially we thought it was going to be a short. We didn’t know that it would sustain. But once we were shooting for a little while, we thought actually this could hold up. So at first it wasn’t as a big of a deal. It was just kind of like, yeah we’re going to shoot for a couple weeks and see what happens and it just worked out.

Was there any resistance from him to be candid and be himself?

It really genuinely feels to me like he forgets the camera is there. I’ve heard him say a few times since we shot the film that he literally was shocked when he saw the movie. He was like “You guys made a movie? I don’t even remember you even being there.”

There is that sense of detachment with Justin not noticing the presence of the camera at all and it creates that fly on the wall experience.

Yeah and again, like at the Guggenheim when for the first time we had the idea for this film, this twenty four year old kid gets up on stage in front of a packed theater and just starts talking to Tyler Peck, who was the dancer that he was working with. It was literally like he didn’t even know anybody was there. And I was just thinking to myself, wow that’s perfect because he’s not going to be bothered by a camera. He’s just so zoned in on her and helping her and making the work better and that’s all he’s thinking about. For me, the first like kernel of making a film like this came from when I was working on Palindromes when I was in college. I was an intern working in the camera department initially and it was my job to move Todd Solondz’s monitor. And I just remember him staring at that box and he would be so into it that he would be lip syncing the lines as the actors were saying them. I just remember thinking, what if there was a camera on top of the monitor with a shot of his face, and doing a split screen of the take and the director’s face next to each other. So I just started thinking about that and in this case it’s ballet, but any film like that or creative endeavor. When someone gets that absorbed by what they are doing, that’s just fascinating to me. So a lot of the film is Justin watching and absorbing what’s happening.

It’s interesting you mention that, because I see a parallel between the way you crafted this film and the way he crafted his ballet. It’s an interesting correlation.

I think anytime you can make a film a bit more personal, even if it’s like a documentary or verité, I think that ends up helping the film. There are some things where I feel like I’ve gone through similar experiences in my career and getting to the next level, having these opportunities. Learning how to figure that out as your doing it and just stuff like that, so I have an emotional response to some of that stuff in the film that probably a lot of people don’t but I think it helped me stay engaged and interested and made the film better at the end of the day.

What was the biggest challenge you faced with shooting this project?

Unfortunately there weren’t really any (laughs).

So it was a cake walk? It was just you and one other person shooting right?

Yeah Nick Bentgen whose an amazing DP and director. We’ve been working for like 10 years or something, he’s great. I think at the time, I was spending a lot of time writing a script and was just staring at a computer screen by myself in my apartment all day. So then when we had a shoot day for this it was like so freeing to get out of the apartment. And also the last few projects I have done have had a crew and there’s a lot of people there, it’s a whole machine. To literally just go to Lincoln Center which is like 10 blocks away from my apartment and there’s a camera there, and I just pick it up and walk into a room and shoot. It was very kind of relaxing in a way.

And also very pure, because it’s you and him in a space doing your thing.

Exactly, so it was really nice. And the editorial process was also really great. Saela Davis who is an amazing editor, this is the first thing that we did together though we’ve done one other thing since then. She really wrote the film in a lot of ways. She’s just really smart and I think it’s the first time that I worked with an editor where I felt they made the film more the way I wanted it to be than I thought it was. So that process was really great too and just being able to walk into the room and feel like someone who really understands the story, understands you and really understands the aesthetic and everything and they crafted this thing and then you can talk about it and make it a little bit better, that was great too. And working with Ellen and Anna, our great producers, so fortunately there was no drama.

Sounds like an awesome experience. In regards to the editing there was an interesting choice you made at the end. [SPOILER ALERT] We see Justin, after having choreographed his original ballet, has also been part of another dance projection that undoubtedly must have been equally taxing.

Well, every dancer at New York City Ballet is usually doing a lot of things at once. They have a huge repertory so there are parts that people do for ten years. For me, it’s my favorite part of the film. It’s sort of like him going back to square one after such a huge triumph especially for someone his age to be working at this level in one of the most important ballet companies in the world. Just to go through that and then go right back and get on stage and dance in a position that is sort of like the lowest rank in the company and just be totally focused on that and totally ready to do it and not have any reservations about it and being totally humble about it. To me that’s great and I think it’s really inspiring how he behaves and chooses to work.

Talk about your cinema verité influence which is apparent in not just this film but others, even ones where you were just shooting.

Yeah I don’t know. I don’t think about it, it’s not a choice for me. I don’t see it as different than the way anybody does anything else. It’s just sort of what is interesting to me. Like this shot is interesting, or this conversation is interesting. This is telling the story, I don’t really think about it aesthetically really and the idea of something feeling real, well it is real. It’s happening and it’s there. So I really don’t think about it, I’m just trying to tell a story and react to what’s happening and that’s what happens. When it comes to narrative film, it’s obviously more planned out but I think it’s the same thing. What is the scene about and it’s not always a process that I’m thinking about it, what do I need to show. It’s more like, this feels right, this doesn’t. And then after the fact I can justify it or if I need to argue for or against something. I think it’s just more like a feeling, like an improvisational feeling especially with verité.

You’ve had a great amount of success coming out of film school. What kind of advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers and cinematographers?

I think something that is really important is doing what you want to do. I think the more that you do things that you don’t want to do, the more you get pigeonholed into that. Obviously you don’t always have the luxury of picking and choosing exactly what you want to do or don’t do, but I think there are a lot of things you can do to get where you want to be. Like if you can not have an expensive apartment or don’t smoke and save fifteen bucks a week and then you can choose what you want to do more. Also a lot of it is luck. The fact that the first movie I was lucky enough to be able to do was with Antonio Campos which was Afterschool, was in Cannes. It’s like well that’s a good start but it’s so lucky. I really feel honored to have been part of that, especially so early. And then it was like I think I can keep doing this if I work really hard instead of doing instead of just any script that comes to you that’s what you take. To me, I don’t think I would be happy doing projects that I don’t like or care about, I don’t think I would do a good job. So if you want to do a good job you have to be doing stuff you want to do then that’s what you have to do. It’s less of a choice I guess than it is me not wanting to fuck stuff up. Because I know myself well enough to know that I’m going to shut off at a certain point if I’m not feeling fulfilled or if the people I’m working with are on the same page.

Is one of your hopes with this film for more people to go ballet more?

Of course. My wife, Ellen Bar who produced this film with Anna, really grew up in that institution. I think my favorite place in New York is Lincoln Center. I want that institution to survive and to grow and to have a new audience. For both of the dance films I’ve made, I tried to make them for people who don’t give a shit about dance and I tried to make them movies. We tried really hard to make it something that people could follow if they didn’t know a single ballet term or know anything about the institution itself. Because to me, it’s not really about ballet, it’s about the creative process in general. So I want people who don’t care about ballet to enjoy this film and hopefully in that process they will become curious about ballet and maybe they’ll want to go see something. Definitely I think they’re going to want to see more of Justin’s work. He’s definitely going to be around for awhile.

Ballet 422 hits theaters on February 6th. Check out Lipes’ Instagram for updates from the filmmaker.