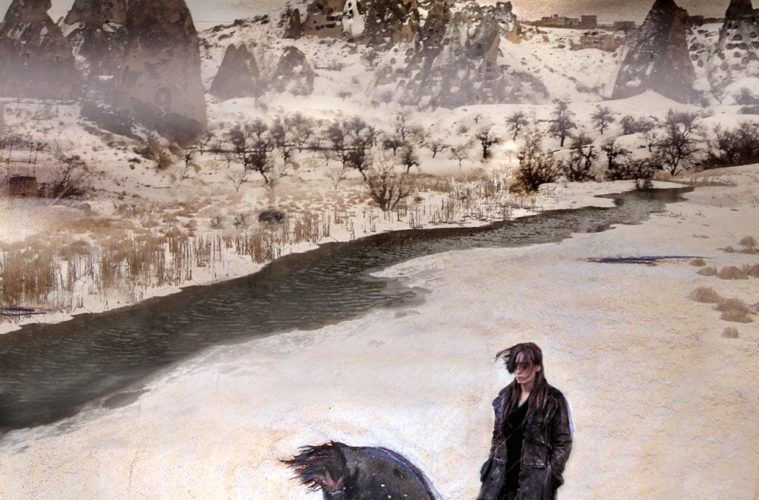

The hotel at the center of the drama in Winter Sleep — both the newest film from Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan and sure to be one of the most-beloved titles at this year’s Cannes Film Festival — sits high above the villages in the remotest part of the Anatolian plateau. The film’s protagonist, Mr. Aydin, lives in a paradise: a majestic collection of small houses for his pile of books, the guests he forms friendly relationships with for brief periods of time, and numerous warm fires that protect him from the harsh oncoming winter. He has also unknowingly built a prison for his sister, his wife, and himself, remaining so closed-off from the world that his thoughts have become deluded.

A brutal portrait of a man, Winter Sleep, for three hours and seventeen minutes, plunges us into Aydin’s thoughts, logic, and feelings as he slowly comes to understand the personality he’s developed over the years. It’s an interesting step for Ceylan, who, after becoming the primary arbiter of Turkish cinema around the globe, seems to be entertaining his own version of Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. He has not lost a focus on the elemental beauty of environment that made both Climates and Once Upon a Time in Anatolia so thrilling, but while Anatolia felt content to be more of a philosophical rumination that only approached the essential nature of its characters when nearing a conclusion, Winter Sleep finds a way to weave these threads simultaneously.

The film begins on a seemingly normal day as Mr. Aydin (the majestic Haluk Bilginer), who has inherited both the hotel and many homes on the plateau, travels with his right-hand man down into the village. A young boy throws a stone right at their car; he is caught, and the stone-throwing turns out to be revenge on Mr. Aydin for the embarrassment put upon his father, who has lost their TV and refrigerator due to unpaid rent on the home that the man owns. (This fact is oblivious to him, along with that both the home and the tenant exist.) Mr. Aydin prefers to stay out of this business, anyway, occupying time by writing a weekly column about things that randomly annoy him (unkempt gardens, imams with dirty feet), and contemplating starting his book on Turkish theater. What makes up most of Winter Sleep, however, are the long conversations with his practically estranged wife Nihal (Melisa Sozen) and his divorced sister Necla (Demet Akbağ).

Anatolia made great use of gorgeous darkened landscapes as a backdrop for seemingly tangential, philosophical conversations. Winter Sleep instead emphasizes its relationships first, using these dialogues to reveal the interior being of its characters. When Aydin and Necla discuss the latter’s idea that, to rid the world of evil, one must simply allow it to happen, it relates directly to the offenses that Aydin feels he is owed by the young boy’s family. Ceylan only doubles this meaning with a later confession by Necla to Nihal about her own relationship with her ex-husband. While the rooms that populate these debates are perhaps less showy than the Anatolian plain, they are carefully art-directed, giving the sense of how these characters have built up their personalities, such as Aydin’s multiple piles of books working as a shield against human interaction. And Ceylan’s shot-reverse-shot dynamic takes on a Rohmer-like quality in their ping pongs; one particular shot that closes out a debate — a long shot that now placed both characters on an equal plain, as opposed to the diagonal one which began the scene — left me somewhat breathless.

Each debate, conversation, and rumination brings us closer to Ceylan’s investigation of the marriage between Nihal and Aydin, details about whom are parsed so carefully over the long running time (their marriage isn’t even referred to until an hour in) due to both the emotional and literal distance between them (they live in different apartments within the hotel complex). Aydin, with his countless thoughts about “morality,” “judgment,” and “ethics,” never realizes the hypocrisy he utilizes in this internal logic to fool himself of the errors of his ways — Nical, at one point, describes him as olive oil that slides through logic to get out of a problem. Bilginer’s eyes often face away from both the camera and the person he is talking to, Aydin preferring to justify himself, as if talking to an unknown audience. Even when Nihal, after being truly tormented by the man (the film is very much a comedy of cringing), explains to him exactly how and why their marriage has fallen apart, Aydin still, in some way, seems outside of the space, jumping right back into his awful condescension.

It is then the film’s majestic third act that brings this two-hour rumination back out into the wild, and each character ends up seeing both of their lives intensely changed as their internal processes are exposed to the outside world. It brings most of the film’s arc to a touching and dramatic close, though the film’s final two minutes include an almost-damning voiceover and one final plot development that threatens to damn near kill the film’s beautiful ambiguity, making everything all too neat and tidy for a film that never truly calls for resolution.

But 195 minutes out of 197 isn’t a bad batting average, and Winter Sleep progresses Ceylan’s ever-evolving narrative and aesthetic strategy into what proves his most emotional and dramatic work, one that makes numerous references to, as well as rivaling, Shakespeare. At one moment, Aydin speaks with a fellow traveler who prefers to live one day at a time instead of through the planned life Aydin has constructed for him and others. As the man speeds off in his motorcycle along the barren plains, our protagonist sits there, wondering what else could possibly exist beyond those hills. But as one of the first shots suggests, what Aydin fears are not the things in front of him; it’s what’s within him.

Winter Sleep premiered at Cannes Film Festival and is currently without a U.S. distributor.