“I can’t stop crying,” Sandra tells herself as she walks through her home. Her phone is ringing, and she needs her pills to calm down. Her fault is not that she is weak; it is that she fears her own weakness.

This might sound like a familiar set up for those who know the work of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the writers and directors of La Promesse, The Son, and now Two Days, One Night. But, once again, the most exciting filmmakers in world cinema have crafted a staggeringly transcendent Parable of the Poor — a view into the dichotomy of work and grace, along with the emergence of self-worth. If one must necessarily ask what is “new” here, it’s that the Dardennes are becoming filmmakers who are abandoning some of their rough-and-tumble style for a cleaner, more elegant form of storytelling, aesthetics, and performance, most notably as this latest masterwork stars The Immigrant’s Marion Cotillard.

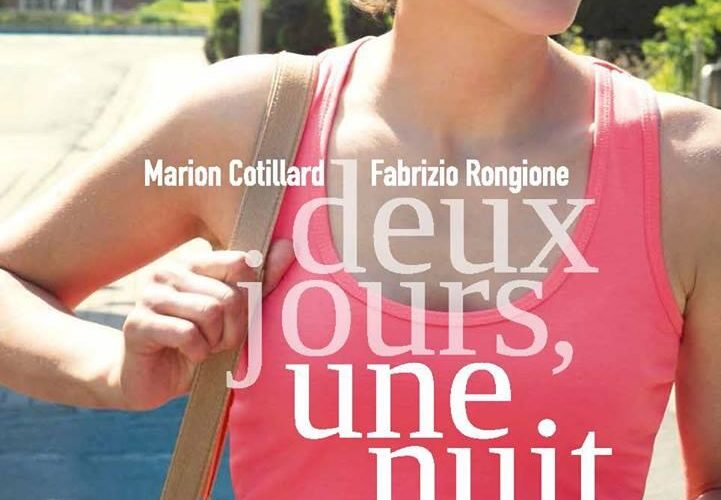

In many ways, Cotillard’s Sandra could be the young girl from Rosetta many years on (her husband, Manu, is played no less by Fabrizio Rongione). Sandra, fighting off the last leg of her depression, has learned that her co-workers at the factory have been forced to vote to receive their bonuses (a sum of €1,000) instead of allowing Sandra to return to her job. Though weak-willed and helpless, Manu and her friend, Juliette, convince her to plead to her boss to allow a second vote after the weekend (this one without the threatening menace of the foreman, enlivened in a brief role by Dardennes regular Olivier Gourmet) to make a final decision. While Sandra is willing to let whatever judgment pass, Manu is determined to force her to fight for her job. When she initially meets her boss, she seems to be cowering from the camera, hiding form its presence.

What separates Two Days, One Night from just another tale of a poor woman in desperate need is that the Dardennes have also, rather subtly, rendered a stunning portrait of marriage on the brink. The film’s structural conceit is simple, as Sandra goes from home to home of each co-worker, trying to fight against every will in her body to be perceived as a beggar while knowing that it is what she must do. These conversations almost take place exclusively in doorways, with Sandra presenting a physical body in order to turn the abstract stakes into manifested reality. The varied moral circumstances of the co-workers weighs heavily Sandra, who pleads to Manu to allow her to simply rot away, reaching the point of making her physically ill — notably in one car-set long take where the woman struggles to simply breathe.

These physical realities — the pushes, pulsating, intensely alive bodies — are what make the Dardennes so thrilling to observe as they craft this superbly calculated melodrama. Cotillard is the intense opposite of Rosetta’s sporadic movements — contained and always shrinking into herself, her voice barely registers more than a whisper. Equaling her is the performance here by Rogione: underplayed but in a way that’s filled with manipulation, embodied with a deep love that often manifests itself through the reach of his hands. He uses them to push and pull her into the world, and the application of these physical gestures to define their relationship (though never sexual) is an astonishing portrayal, unlike any other film about marriage I’ve seen. When Sandra reaches for Manu’s hand while driving a car, it carries the simple but intensely felt construction of her offering the love she’s otherwise rejected.

On the surface, Two Days, One Night is a cleaner film: it’s inhabited with less of the aesthetic immediacy from their earlier works, perhaps reflective of a small move up the social strata. More than that, the push toward classicism creates an environment that opens each shot to the purity of the gestures. The takes are more broken-up — more shot-reverse shot, but the Dardennes still use their moving camera to find compositions which place these conversations on the planes that articulate the great physical (and often spiritual) divides between individuals. The stakes of the film ever so slowly add up, not just as Sandra gets closer and closer to the necessary number of votes, but as she slowly sees the various consequences (not all who vote against her are monsters), which leads her deeper into fear — but simply the fear of pity, of not seeing that lowering herself to begging means her whole being must be lowered as well. Those consequences, however, also mean something for Sandra — she is worth something to each of these people, for better or for worse.

Two Days, One Night premiered at Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Sundance Selects.