In an era where the aesthetics of animation uphold the crafting of a stunning amount of detail into the image, one of the most genuine pleasures to be found in The Tale of Princess Kaguya — the first film by Studio Ghibli auteur Isao Takahata in fourteen years, and likely his last — is not that each frame bursts with multitudes of details, but with barely the minimum. It is often as if the colors of the background are unfinished, every shot like a brief sketch than something meticulously worked over. In an era where anime films seem to blend into each other aesthetically, Takahata’s impressions seems marvelously alive — its modesty in images makes them feel as if they’re being created before our very eyes.

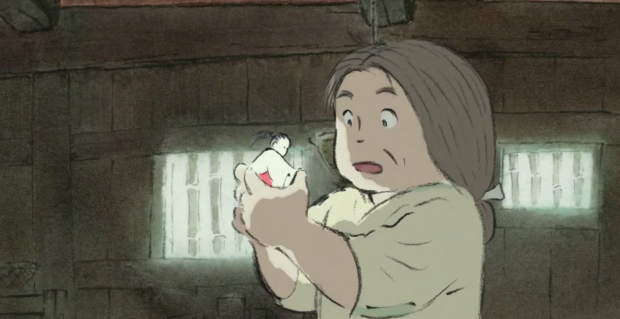

It’s a shame, then, that a film created with such passion can also feel so impenetrable. Kaguya is based on a 10th-century folk story best known as “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” and it’s very much still a folktale. The film opens on a woodcutter who, one day, finds a tiny princess hidden inside a bamboo stalk. He takes it home to his wife, the tiny sleeping princess suddenly grows into a baby, and the wife’s breasts are suddenly ready for milking (the film can be surprisingly frank in its sexuality). Soon, they find gorgeous golden robes, realizing that this young child is destined to become a princess.

This is fascinating material for a director who has been labeled “the neo-realist of Anime” — a very peculiar phrase, if you think about it — with films like Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday to his name. It’s also very tricky in a way common to many folktales: the character of the princess — who goes from her young adventures in the forest to the rigorous world of the feudal city — remains psychologically cryptic. Her motivations appear to violently shift from scene to scene in many way. She hates the rigidity, but she’s excellent at it; she misses nature, but rejects it as soon as she return to it.

As a folktale, it’s easy to imagine “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter” being a fantastically orated story. But, as a psychological medium, The Tale of Princess Kaguya has a narrative that moves without logical motivations, making it somewhat tough to find an entry point. The final third, which suddenly re-inserts the film’s more fantastical elements without any preparation, seems so divorced from the action which preceded it that I can only compare this film’s narrative to poetry, though not in a way resembling the Japanese Golden Age masters. (Some have compared Kaguya to the works of Mikio Naruse, however.)

Yet this is a picture with a style so rapturous that it’s hard to find the images pleasurable in and of themselves — even when depicting the faces of two characters, a quiet temple, or a forrest of bamboo, Takahata chooses images that are striking for their simplicity, not density. This can be as simple as the movement of a body; seeing them dance through the forest, jump up and down the beautiful mansions of the city, and, by the end, fly through the air can be a magical experience.

It’s hard to know what to make of The Tale of Princess Kaguya — just in terms of distribution, it seems even more inaccessible to the American market than The Wind Rises. It’s a film that creates a hypnotic power with each individual image, be it the popping of cherry blossoms or a parade of magical creatures raining down to the Earth on a cloud. But those images seem to richoet off each other instead of build into something a magnificent climax. Is it, at the end, a tragedy? A tale of homecomings and homegoings? To the distant observer, it is hard to grasp.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya screened at Cannes Film Festival and will be released by GKIDS. See a new trailer above.