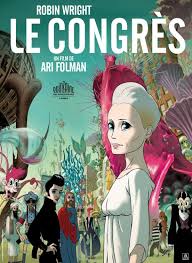

Trippy, bizarre, surreal and hallucinatory are all excellent adjectives with which to describe Ari Folman‘s The Congress. Adapted from a novel by legendary sci-fi author Stanislaw Lem (Solaris), the film is a hybrid of live-action and mind-bending psychedelic animation; as this is the filmmaker’s follow-up to Waltz with Bashir, those familiar with that title know that Folman is far from a traditional filmmaker. Utilizing the animated format in unexpected ways, his rotoscoping technique — otherwise best known to those who’ve seen Richard Linklater‘s Waking Life or A Scanner Darkly — breathes a level of organic movement into otherworldly 2D animations. With The Congress, Folman has attempted to bridge two realities into a single ambitious and highly stylized window into the future of filmmaking.

The film features Robin Wright as herself, albeit an exaggerated version living with two children in a repurposed air hanger that has been transformed into a home. In The Congress‘ first, entirely live-action half, we can sense at play meta-theatrics that are oddly reminiscent of films such as Being John Malkovich and last years Cannes entry, Holy Motors. Wright, who has not had a major film role in several years, becomes persuaded by her agent (played with sly charm by Harvey Keitel) to have her physical body and emotional states digitized into a computer. The reason being that a movie studio, cleverly titled Miramount, has developed a technique that allows them to make films using these digital archives of famous actors — but it also robs them of their identity.

This self awareness and critique of the current state of cinema is compounded about halfway thru when the film veers into a Roger Rabbit-esque animated zone wherein people hallucinate their painful realities away into an ether of dreams and fantasy. (A truly magical sequence involves Robin Wright driving her car down a highway as the real world slowly transforms into an animated sequence that feels to be taken straight out of an acid trip.) The justification for the world becoming a cartoon is a bit confusing, but it’s difficult not to be immersed and overjoyed at the details contained in each frame. Be it caricatures of famous people (Tom Cruise and Michael Jackson) or works of art that come to life (the Venus de Milo and Magritte‘s Son of Man), Folman cleverly hides an entire meta-universe of artistic references in the backgrounds of his colorful tableaus as Robin Wright desperately tries to make sense of it all.

While not without its issues across some aspects (some of the live-action scenes feel a bit stilted), one can overlook these faults in favor of the grand scope and ambition of Folman’s larger oeuvre. This is a man pushing the boundaries of what’s possible within the realms of cinema, proving that, if you have the imagination to dream big, you can execute some remarkable feats. Reception to the film has been generally divisive among critics — similar, again, to last year’s Holy Motors — but it feels primed to be embraced by the larger public audience whenever it arrives stateside, even if only for its purely original spirit.

Delightfully surreal and spectacular in its scope, The Congress is a strong testament to the originality and talent behind Folman’s vision of where cinema can take us in the years to come.