Being the same age as Xavier Dolan (25), I can say that it is quite an impressive feat to already have four highly acclaimed features under your belt. And while the ego exuded in interviews has perhaps been a smidge unbecoming, that’s not an issue, per se; many of our great film artists often are complete assholes in interviews — Mike Leigh and Spike Lee are but only two prominent, contemporary examples — instead letting their work speak for itself. Mommy, Dolan’s first film to bow in Competition at Cannes, certainly speaks loud and clear for the director’s ego from its initial frame — which is to say that Dolan has decided to frame his action in a 1:1 aspect ratio, best described (already ad nauseum) as similar to an Instagram photo. A bold move, but also a loud formal conceit that limits the creativity of a director who’s found interesting framing and performance in the past with Heartbeats and Laurence Anyways. In Mommy, Dolan has essentially stunted his work, speaking both figuratively and literally.

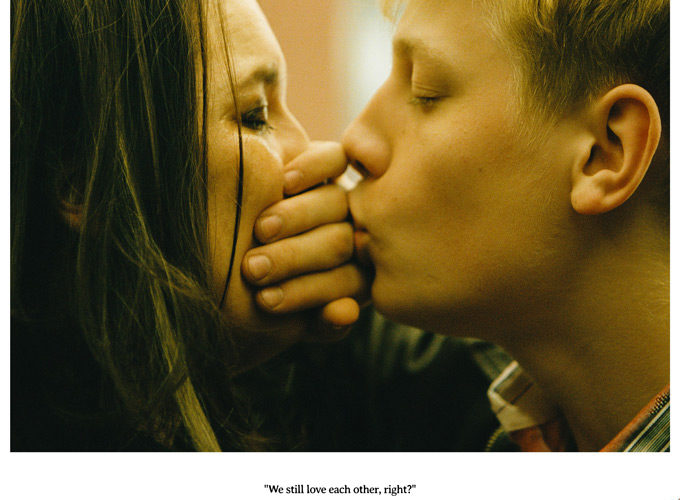

Opening with title cards that speak of a “fictional Canada in 2015,” where a new law allows parents to place their children in institutions without any legal proceedings (Chekov’s Mental Ward), Mommy follows, what else, a titular mother, Diana (Anne Dorval, wearing a gold chain bearing the word “mommy”), preparing to once again unite with her son after his time at a boarding school has gone awry. Diana, who goes by “Die” (irony!), is hardly fit to take care of him, who, we are told, is on the edge of poverty — though money never turns out to be an issue in terms of their worldly possessions and home. The boy, Steve (Antoine Olivier Pilon), is probably not ready for some real-world experience; he’s wildly erratic, physically combative, and runs a motor mouth like no other. But Diana loves her son, and Steve loves his mother, so the two decide to run around their house and neighborhood like lunatics who make Edward Albee and Tennessee Williams plays seem restrained.

But that’s not all: Dolan has made a three-person tale, with Kyla — played by the wondrously subtle Suzanne Clément from Laurence Anyways — complicating their fights. Kyla is a depressed housewife next door who’s gained a speech impediment, taking an interest in the mother-son duo after they seem to take notice of her. (Why her husband takes zero interest in her visits with these psychopaths is a total mystery.) It’s doubtful how much Kyla’s own recovery narrative actually fits within Dolan’s narrative — it becomes obvious that she’s simply a lynchpin for the drama to have an observer — but Clément makes the character feel vividly alive, counter to the way Dorval and Pilon’s constant screaming lacks anything resembling subtlety or psychological realism. She brings an emotional pull to the speech impediment device, making it feel authentic instead of like a tic and allowing her quiet moments to sink with authenticity; the first time she threatens Steve is an intimately tense moment that actually feels like a breakthrough for the character.

But this acting is all in favor of something totally and tonally bizarre — a complete lack of narrative structure. A tender moment, often accompanied by something from a ‘90s mix tape (Counting Crows, Eiffel 65, Dido, Oasis), is interrupted by a sudden moment of anger and yelling, only to calm down a few minutes later, only to start back up with a sudden cut to a new scene. It’s not that Dolan has no sense of melodrama — it’s that he has no sense for using it as a structural device to carry us anywhere. Individual scenes may wield their power, but there’s zero sense that they build on one another, or even that we are gaining psychological insight through any single fight. His music-video “freedom” sequences are nice little tidbits, edited with rhythmic cutting, but they don’t push the characters forward, simply acting as reprises for the paltry drama.

More egregious than the poorly planned drama is how Dolan has limited himself, formally. Shooting in 4:3 (e.g. Laurence Anyways) still gives one plenty of space to compose each shot with a psychological insight. The 1:1 aspect ratio gives Mommy a palpable sense of claustrophobia, but this effect wears off minutes into the film. Because of the limited amount of space, the compositions are often one shots of the characters or two shots crammed into the frame. Without negative space to work with, Dolan’s work simply sits on the screen without much internal meaning; he’s limited to the necessary space without much room to consider exactly how his characters should be framed to psychologically engage them. There is some formal play with foreground and background in a few moments — and, occasionally, Dolan steps his frame back far enough to find something that actually speaks to the character’s emotional status (especially with Kyla, who has the most room to change within the drama) — but too often do the frames seem somewhat limiting. They capture the faces in the only way the camera allows them to, and the film’s two changes in aspect ratio are, frankly, a bit silly as well — a clever metaphor for the so-called “opening-up” of the characters.

Dolan is an impressive director who’s made a career out of his musical interludes and some tremendous performances. However, Mommy shows he has little tenacity for the actual materials that make up a narrative film, as the elements which made his previous pictures exciting get trapped in a mess without anything palpable to grasp. Its emotions are so convolutedly constructed that there’s no breathing room to really investigate the relationship at its core. Dolan drags us to the picture’s only inevitable conclusion — that opening title card has to figure somehow, or there is no reason to include it — which finally plays as a sigh of relief when the exhaustion mercifully comes to a close.

Mommy premiered at Cannes Film Festival and is currently seeking U.S. distribution.