If there is a very loose thread connecting contemporary Russian cinema to its artistic heritage, it is that its best filmmakers still exude a desire to produce art on the grandest of scales. The great Czarist-then-Soviet-then-Thaw State has amalgamated a collection of artists known, in some circles, solely for their grand scale: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Bulgakov, with their intense emotional overtures that turn simple stories into mass-size tragedies; the overtures of Tchaikovsky, with their use of bellowing brass and percussion; and Kadinsky’s extreme use of space in his abstractness. Of course, there is its cinema: Eisenstein’s lightning-like editing, Tarkovsky’s profound stillness, Sokurov’s investigation of power — and, now, Andrey Zvyagintsev‘s intensely operatic examination of a land dispute escalated to epic proportions in Leviathan.

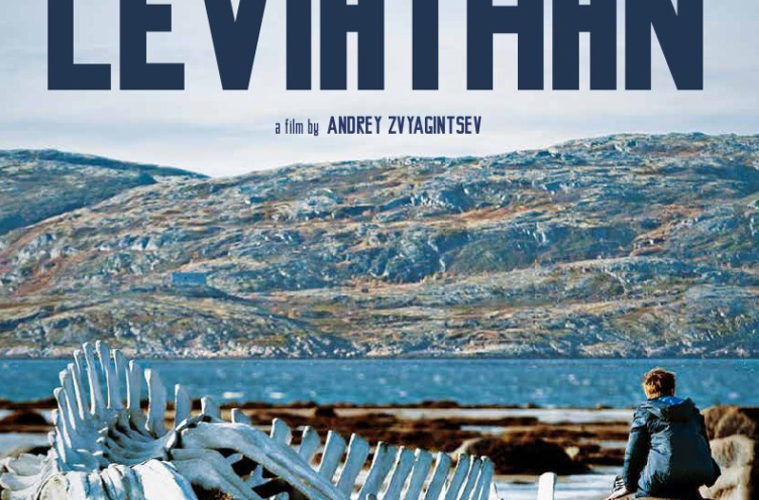

It seems almost like parody then that the filmmaker opens his story — one with human proportions that are ultimately so small — with epic landscape shots of waves crashing against the state’s deadened coasts, paired with images of broken ships at least a century old while Philip Glass‘s score pulsates doom. But Zvyagintsev drops this grandiose scale for something more slyly comic for a while, weaving his tale of a Russian family torn apart for inexplicable reasons. The director’s last film, Elena, told a similarly personal-made-epic tale, in which the wife of a rich husband committed murder to secure her impoverished son’s future, indicting all of Russia’s unspoken class system in its wake.

Leviathan certainly has many unspoken race and class issues brewing under its intensely restrained surface. The film begins as Koyla (Aleksey Serebryakov) has raised a lawsuit against the mayor, Vadim (Roman Madyanov), for illegally seizing his property, and has recruited a Moscow-settled childhood friend, Dimitri (Vladimir Vdovichenkov), as his lawyer. But the verdict is not a favorable one — the judge monologues an incomprehensible explanation at a lighting-fast pace in a single take that is ridiculously funny, a Kafka-esque moment laid down like an edict from God.

For a state that suppressed religion for more than half of the 20th century, Christian faith plays a central undercurrent throughout Zvyagintsev’s moral drama, with two priests (a “modern” one and a highly Orthodox one) delivering various sermons to the characters engaged in this fight. These lectures at many points prove overwhelming to the carefully attuned performances and narrative beats that otherwise rely so little on direct exposition. More and more, faith becomes a sole explanation for the incomprehensibility of events at play. What begins as a land dispute slowly turns into a war of word — which leads to a jail sentence, which leads to corruptions charges, which leads to an affair, which leads to a murder, etc. etc. etc. (This is along with a lot of consumed vodka.) Koyla finds himself baffled by proceedings which, after the opening, unfold without his own agency, rendering the emphasis on faith (Zvyagintsev claims Leviathan is his take on the Book of Job) somewhat essential as the plot becomes somewhat ambiguous — a disappointing appeal to didacticism that seems beyond the director’s subtle showcase.

But those elements only slip themselves into the narrative near the very end; otherwise, Zvyagintsev has crafted Leviathan with the most sublimated of directing, letting each scene play out with a quiet, methodic use of pace and performance. In one way, his style could remind some of the overused conception of “slow cinema,” but each shot takes on a methodical economy — each line of dialogue and image (mostly master shots, but occasionally done in shot-reverse shot) answers the last, building an environment of paranoia. These carefully composed widescreen frames create an intensely rigorous space for which the camera often moves in lateral shots along, while also creating fascinating compositions through a play between foreground and background spaces to create the dynamics of power as they rise and fall through the narrative. He even includes many shots in which characters exit the frame, holding them until they return to the space — just when peace may be had, the masculine forces kick right back in.

Leviathan premiered at Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Sony Pictures Classics.