Deadpan comedies are a trademark of Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismäki. He specializes in creating atmospheres devoid of overtly acted emotions, opting instead for subdued reactions and simplistic camerawork. These attributes play to his strengths in creating still life portraits of bizarre situations that force his characters to react in a similarly odd and ironic manner. In Le Havre the director returns to France to create a morality fable about the ever increasing problem of immigrants fleeing their home countries in seek of a better life. Set in the fishing town of Le Havre, the film is perhaps Kaurismäki’s most accessible to audiences unfamiliar with his style and a veritable pleasure to experience.

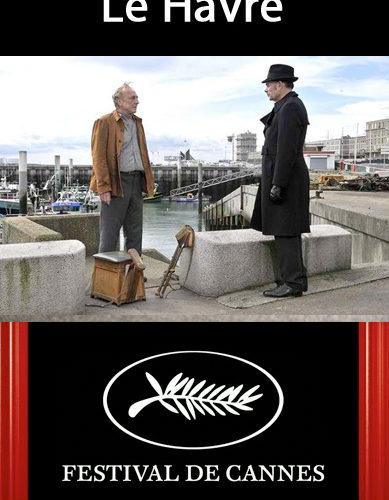

The plot centers around a former author Marcel Marx, played with gentle humor by veteran French actor André Wilms, who has now become complacent with his job as a shoe shiner. Bouncing around town from the local bar to his modest home where his wife Arletty (Kati Outinen) takes care of his every need, Marcel relishes the simplicity of his life. But all that is about to change when a young African boy by the name of Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) escapes a cargo hold and seeks refuge with Marcel after a random encounter. Hot on his trails, dressed all in black, is Detective Monet, played like Detective Clouzot by Jean-Pierre Darrousin, who will stop at nothing to uncover the location of the boy. Making matters worse for Marcel is the fact that Arletty has fallen ill while the boy has taken hospice in their abode.

As the game of cat and mouse continues to unfold, Marcel searches for a means of returning Idrissa to his family. The point Kaurismäki is trying to make is two-fold. On one hand, the director wants to highlight the kindness of the local townspeople who in their hearts want desperately for the boy to reach his destination of London and reunite with his mother. The other side of the coin is the much more serious issue that Europe is facing with refugees pouring in from surrounding countries. To its success, the tone never becomes overtly serious while dealing with extremely difficult issues, part of the brilliance in Kaurismäki off kilter style.

Le Havre is a moving portrait of how a town can come together to help a young boy succeed in reuniting with his family. Shot in an vintage cinema style (apparently with a camera once used by Ingmar Bergman) and full of wit, humor and tenderness, this is an example of a director in top form. Sure to please the European audiences, it would be interesting to see how this semi-realistic fairy tale would fair abroad. The issue of mistreatment of refugees trying to find their way into the EU is something that many countries can identify with. In Kaurismäki’s world, he opens our eyes to the countless poor impoverished souls searching for a home.