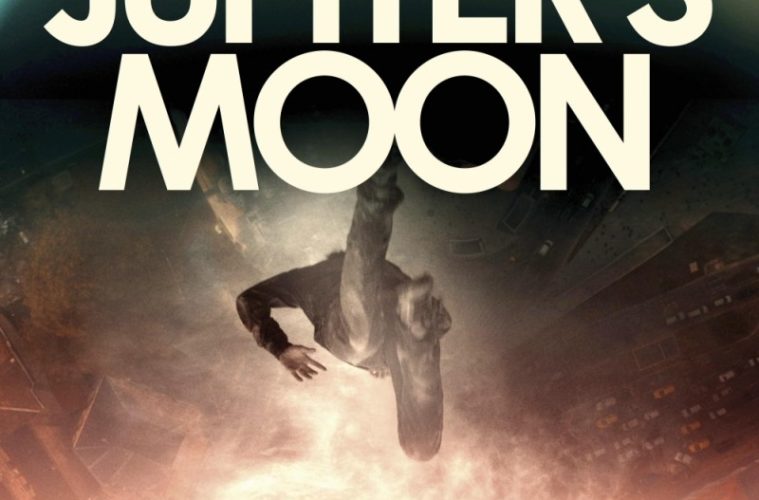

The juxtaposition of supernatural thriller tropes and urgent socio-political issues in Kornél Mundruczó’s latest movie — an original take on the superhero origin story set to the backdrop of the refugee crisis — might prove a delicate one for some viewers to take. Those unperturbed, however, should find much to relish in Jupiter’s Moon, a film that somewhat lightly plays with themes of religion and immigration as it rumbles, crashes, and ultimately soars through the streets of the Hungarian capital. It’s a tricky balance and Mundruczó (who had a break-out with his canine revolt film White God in 2014) strikes it with style and confidence (even going so far as to signpost it in an opening prologue that reminds the audience that the titular gas giant’s largest orbiting body is called Europa, and that many believe that large oceans rest beneath its icy surface where a “cradle of life” might exist). The hero of Jupiter’s Moon, a young Syrian refugee with the connotation heavy name of Aryan (played by Majd Asmi), does not find a cradle of life in his Europa. To the contrary, in fact, he’s gunned down in the opening minutes.

Mundruczó plunges the viewer right into the action with an immersive beach landing sequence (note the echoes of Saving Private Ryan) as Aryan and a group of refugees attempt to cross the border into Hungary. Moon is perhaps at its best in such kinetic moments, not least an inspired scene later on when an apartment is spun around like a washing machine. Aryan is not really killed in the shooting, of course, but instead rises with the inexplicable ability to levitate. Is he a superhero, our savior, or a very naughty boy? It’s difficult to tell.

He will later arrive in a refugee camp near Budapest where a disgraced surgeon named Stern (Merah Ninidze) witnesses his gift and cynically decides to take on the role of a Svengali, convincing Aryan to use his abilities to make a quick buck. Nearly every character in Mundruczó’s film is driven by similarly self-serving motivations and it will take them a while before choosing to consider that Aryan might just be a representation of something bigger than themselves.

Perhaps therein lies the crux of Mundruczó’s story. There are a number of times throughout when Aryan rises above whatever chaos is happening on street level (the loudest being a bomb strike on the underground that the man is later accused of) and lies suspended in peace above the rooftops. Cinematographer Marcell Rév shoots it with drones, cleverly allowing the audience to see the reaction of the civilians as they first forget what’s happening around them before falling to their knees in disbelief, perhaps in prayer. You’re reminded of how the soldiers react to seeing the newborn baby in Clive Owen’s arms at the end of Children of Men. Indeed, the influence of Alfonso Cuarón’s film can be seen in almost every scene of Mundruczó’s film: in the handheld camerawork and wide-angle lenses; in the unshaved men in knackered trench coats shuffling around hopeless looking streets; and in the lighting, staging and elaborately choreographed long takes. There are worse and far less technically difficult films to replicate. Praise should be given for doing it so well.

The most abstract connection, perhaps, is the rather clunky idea that squabbling humans might just forget their differences for a moment if united by some grand event or greater good. The subway bombing turns Aryan into public enemy number one and the police will duly hound him for the rest of the movie, but in the midst of it all Stern — still haunted by a surgical procedure he botched a few years back — begins to believe that a higher power might indeed be at work and so turns from exploiter into pseudo-disciple. Even the film’s chief antagonist — a worn-out/devout detective named Laszló (Gyōrgy Cserhalmi) who is responsible for Aryan’s shooting at the start — begins to question his own beliefs and actions. Such pious departures, however half-baked and pretentious, only add to the pleasure and mystery of this strange, oft derivative, but undeniably unique genre outing.

Jupiter’s Moon premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. See our coverage below.