Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2022, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

From a broader point of view, 2021 was a tough year for cinema, and in some ways 2022 was even tougher. Most of the films that came out were produced during the pandemic, and in a lot of cases it showed. Many films felt scaled back, with a more intimate scope that sometimes resulted in awkward pacing or compromised edits. For the films that could afford to spend some extra cash, titles like Jordan Peele’s Nope and Damien Chazelle’s Babylon were self-aware rallying cries for the spectacle and grandeur of the movies, all major efforts to go big in order to coax audiences into seeing them big. The results of those gambles were mixed at best. Maybe it’s me looking into things too much, but it might mean something that the most successful film of 2022 at the box office, Top Gun: Maverick, was finished before 2020.

And yet, cinema, and the people who make their living off of it, persisted. Major film festivals like Cannes and Toronto put all their chips in marketing that film came roaring back in 2022, but the public didn’t show the same sentiment for the kinds of movies festivals typically show. Barring a few exceptions, limited release titles collapsed at the box office, and even award voters wouldn’t show up for free screenings booked exclusively for them.

I’m not intending to be obsessive over box office numbers (sorry Marty), but the less money movies make the less likely people and businesses will keep investing in them. And after enduring a year of whiplash between perception and reality from the film industry, I can’t just list my favorite movies of 2022 without acknowledging the fractured state of things. No, cinema isn’t dead, and it hasn’t returned because it never left, but the circumstances and viability have changed significantly over a short amount of time. How we navigate our way through that is crucial to finding our way out of it, and my hope is that where we land will allow films like the ones below to exist and find people willing to engage with and support them.

With all that said, here are my favorite films of 2022.

Honorable Mentions: Met mes, A Human Position, There There, The Banshees of Inisherin, Rewind and Play

10. Funny Pages (Owen Kline)

It would be so easy for Owen Kline’s film to fall into caricature and cruelty, with its cavalcade of bizarre characters almost begging people to laugh at them (and if you’re on this film’s wavelength you will laugh a lot). But Kline refuses to give viewers an inch of distance from his ensemble, dropping them right alongside his film’s teenage protagonist, an aspiring comic book artist who has his worldview and standards of art shredded by the eccentrics he looks up to. Whether it’s the dirty setting of a wintry New Jersey, a nauseating basement apartment, the chaos of a pharmacy visit gone wrong, or the worst Christmas day imaginable, Funny Pages’ commitment to specificity and squalor somehow makes it work as a loving ode to outsider artists.

9. The Maiden (Graham Foy)

Apologies for lazily referring back to my write-up for The Maiden in this site’s round-up of the Best Undistributed Films of 2022, but I’d just write the same thing again in a different way. Graham Foy’s film is the best directorial debut I saw last year, it’s a fascinating portrait of grief, coming-of-age, and suburban malaise that opens itself up in unexpected ways. It’s not the only Canadian film on this list, but I’d say it’s the one that has me the most excited for what the future might hold for Canadian cinema.

8. Pacifiction (Albert Serra)

I love being proven wrong with movies, where I might have an opinion I feel so strong about and then find those beliefs turned upside down. I always had a disdain for Albert Serra’s films, which are usually a chore to sit through, containing a wisp of an idea executed with a ton of arthouse posturing that fans would eat up and treat naysayers with a condescending, “you just don’t get it” attitude. But Serra’s latest film, which might be his most ‘mainstream’ work to date, sits on my top ten. Maybe I just got more out of what he did this time, which has Benoît Magimel as a French government official in Tahiti growing paranoid as he hears rumors of backroom talks about nuclear testing he’s not aware of. Almost every frame of Pacifiction is ravishing to look at, Magimel gives one of his best performances to date, and Serra does a great job using his main character’s increasing irrelevance to push his film into a liminal space. If you’re able and willing to see this one theatrically, you should.

7. The Dream and the Radio (Renaud Després-Larose and Ana Tapia Rousiouk)

Once again, I’ll refer back to my write-up for The Film Stage’s Best Undistributed Films list, but I am disappointed at how quickly The Dream and the Radio vanished after its premiere at Rotterdam in January 2022. Parts of this film still linger in my mind despite having seen it almost a year ago, and it contains some of the most flat-out beautiful shots I saw in a movie over the last 12 months. Wherever this film ends up, I hope it will have a chance for more people to discover it.

6. The Eternal Daughter (Joanna Hogg)

Joanna Hogg’s two Souvenir films were a mixed bag for me, but somehow The Eternal Daughter worked like gangbusters for me despite covering similar meta territory. Maybe it amounts to the difference between autobiographical films and personal ones, as this film exists more in a fantasy world, where Tilda Swinton plays a filmmaker taking her mother (also played by Swinton) to a gloomy Welsh hotel and finds herself trapped in a BBC ghost story. What starts out as a strange genre riff slowly unfurls itself to reveal something more complex and emotional, with a heavy emphasis on the fear and anxiety as one’s parents get older. The Eternal Daughter is still a genre film through and through, it’s just one about the ghosts we make up and haunt ourselves with.

5. EO (Jerzy Skolimowski)

While not my favorite film of the year, EO is the one that’s the most fun to talk about. It’s got donkeys, crazy drone shots, a robot dog, Isabelle Huppert smashing plates, and so much more. It’s an 84-year-old director exerting more creativity and energy than an entire 30 under 30 list of filmmakers. It’s big, bold, and experiential in ways that highlight cinema’s strengths as an art form better than any big-budget tentpole. And it’s more accessible than it sounds, with a short runtime and an episodic structure that demands you give yourself over to every whim and impulse it pursues. If you don’t see EO, you’re missing out.

4. The Eight Mountains (Felix Van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch)

When I saw The Eight Mountains at Cannes, it was difficult finding anyone else who liked it as much as I did, which is understandable. It’s a long, intimate story about two childhood friends from an isolated village in the Italian Alps, who cross paths over the decades as they figure out their own lives and try to find some sense of contentment. It’s restrained and sincere, ambitious yet humble, and unafraid to get sentimental. It’s not going to work for everyone, but I found its graceful way of weaving in large, existential ideas around the film’s central friendship both effortless and moving. Not many movies can tackle the totality of life with an awareness of how our own actions and inactions weigh on us as we get older; The Eight Mountains pulls it off with a modesty I rarely see.

3. Tori and Lokita (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne)

Somehow, after winning two Palme d’Ors and influencing a slew of copycats since 1999, the Dardenne brothers have fallen out of favor, their brand of humanism no longer having a place for what’s trending in arthouse cinema today. The Dardennes haven’t changed though, and neither has their power for showing how social and political forces influence and dominate the lives of the most vulnerable. In what might be their angriest film to date, Tori and Lokita follows siblings and undocumented immigrants in Belgium as they’re forced to take desperate measures to get by. The Dardennes are unflinching in their portrayal of institutional failures stack the deck against both characters, and how every degrading and life-threatening choice they make is forced upon them by systems designed to devalue them. Some people may be tired of the Dardennes’ style by now, but they remain as strong as ever, often imitated and never duplicated.

2. Crimes of the Future (David Cronenberg)

David Cronenberg’s first film in almost a decade was thankfully worth the wait, and while a lot of critics took to Crimes of the Future’s look at an aging artist (Viggo Mortensen), I was more drawn to the eco-horror elements. Set at some unknown amount of time from now in Greece, humans have started developing new organs, no longer feel pain, and are immune to diseases. There’s a dead body at the center of it all, which turns out to be the symbol for Cronenberg’s vision of a horrible, resigned future: after shaping our world and environment with mass consumption and waste, it’s the world’s turn to shape us, as our bodies evolve to consume plastics and toxic waste in order to continue to survive. Most eco-thrillers portray humanity’s hubris as a tangible threat that can wipe us out of existence; Cronenberg shows our demise as a gradual shift into something inhuman, the accumulation of our destructive ways coming back to haunt us in ways we never expected. Naturally, Cronenberg doesn’t look at this potential future with shock or bemusement. He treats it with a shrug, a change (or inevitability) we have no choice but to embrace, which makes it all the more unsettling.

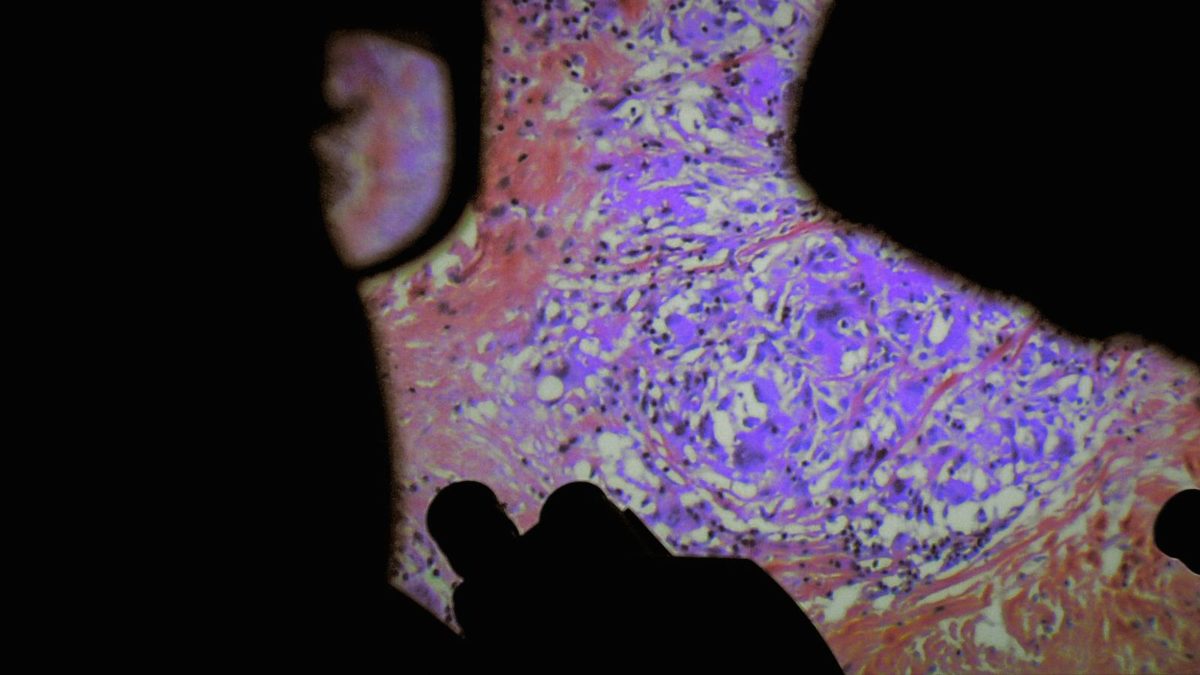

1. De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Paravel)

In 2012, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel used GoPro cameras in the Atlantic Ocean to make Leviathan, which turned the seas, fish, and birds into a horrifying, abstract display of all-encompassing terror deserving of the biblical title. Ten years later, they turn their sights (literally) inward with De Humani Corporis Fabrica, which was filmed over several years at different hospitals around Paris. Using small cameras, they attach their equipment to surgical tools, giving a way too up-close look at brains, prostates, spines, and other body parts. At first, the distressing nature of the images suggest another round of horror like Leviathan, then over time the footage takes on a different meaning. Bodies become strange, complex landscapes and realms; the winding hallways of the hospitals share similarities with the structure of the human body; and the audio of hospital staff show off a self-imposed distance they maintain in order to perform their jobs. Like Leviathan, De Humani Corporis Fabrica redefines the way we see the world, only this time in a way that inspires awe more than fear.