Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2021, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

It goes without saying that the past two years have been a lot for everyone to deal with. There were plenty of films released in 2021, but every aspect of the industry suffered through it. Productions dealt with new, costly protocols, festivals had to navigate physical and / or virtual events, distributors chose between theatrical exclusives or hybrid releases, exhibitors did everything they could to stay afloat, and everyone lost a ton of money in the process. There is no easy way out of this pandemic, but that’s not stopping anyone from burning through everything they can to find one.

Still, there were lots of things to see in 2021, and the spread of great to good to bad wasn’t particularly different from any other year. Some films that held off screening until things were safer (whatever that means anymore) were worth the wait, while others could have stayed in limbo; films made during the pandemic either leaned into the state of things or avoided it altogether, giving filmmakers the choice to make two kinds of time capsules; and every movie tried to simply get by, fighting for relevance and profitability in a still compromised market.

For my own sanity, I based my top 10 this year off films that had their world premiere in 2021 rather than by general release date. Some of the titles here either have no distributor or haven’t come out yet, but hopefully these distinctions won’t matter in the coming months. Here are 10 of my favorite films from 2021, and here’s to an ambivalent 2022 and beyond.

Honorable Mentions: The Tale of King Crab, Benediction, The Girl and the Spider, Rock Bottom Riser, Vortex

10. Bergman Island (Mia Hansen-Løve)

“Bergman was as cruel in his art as in his life,” says one of the people keeping Ingmar Bergman’s legacy alive on Fårö, the small island where Bergman called home and even made some of his films. The line feels like a challenge writer/director Mia Hansen-Løve sets for herself: can she make a film that deals with life’s cruelties without making a cruel film? Hansen-Løve’s ability to meet that challenge isn’t what makes Bergman Island so special. What makes it such an achievement is the way she goes about it, creating a space on the island setting that’s open to all possibilities (including a narrative change-up at the halfway mark) and filled with ambiguities. Revisit Bergman Island and you’re likely to find lines of dialogue, actions, and reactions take on different meanings, suggesting underlying resentments or unresolved feelings. Hansen-Løve lets these moments linger rather than entertain any explanation or resolution for them, leaving viewers to connect the dots as they please or just enjoy the laid back, melancholic vibes.

9. Bad Trip (Kitao Sakurai)

Kitao Sakurai’s hidden camera comedy Bad Trip was supposed to come out in theaters in 2020, until the pandemic made Paramount sell the film to Netflix instead. It’s an unfortunate outcome for a film that would have brought the house down had it screened for audiences instead of home viewing. More than just a collection of hilarious, raunchy pranks on unsuspecting people, Bad Trip takes on the narrative of a standard road trip comedy and bends reality to its will, making participants unaware co-stars rather than a series of marks to be made fun of. It’s a closed loop of life imitating art and art imitating life, making us laugh at the way tropes and cliches fail to translate into the real world before surprising us when the targets recognize them and rise to the occasion.

8. Red Rocket (Sean Baker)

Ugly truths pop up throughout Sean Baker’s Red Rocket, which looks at a washed-up porn star Mikey (Simon Rex) as he returns home to his estranged wife (Bree Elrod) and works his sleazy charm to woo a teenager (Suzanna Son) so he can use her as a way back into the industry. Baker’s decision to center his story around an asshole won’t please everyone, but there’s more going on than an unpleasant protagonist. With his non-stop hustling, aggressive charisma, individualist attitude and quest for a comeback, Mikey embodies the rot of values that used to be celebrated as the things that made Americans exceptional. It speaks to the talents of Baker, co-writer Chris Bergoch, and the cast (Rex, Elrod, and Son give three of the best performances of the year) that these ideas come out of the film organically, an emphasis on showing over telling that has expectedly rankled viewers who have come to expect films to make up their minds for them.

7. Wood and Water (Jonas Bak)

One of the best debut features of 2021, Jonas Bak’s Wood and Water takes a familiar story (an older woman getting more in touch with herself later in life) and tells it in a way that feels completely original. Starting out in Germany’s Black Forest region, a newly retired widow and mother (played by Bak’s own mother) makes an impulsive trip to Hong Kong to see her son, who claims he can’t leave due to the ongoing protests in the country. Shooting on 16mm, the imagery takes on a dreamlike quality before a standout sequence where the rural Black Forest seamlessly transitions to the busy streets of Hong Kong. From there, Bak shows his mother adapting to the cityscape, connecting with several people while she waits for her son to return from a trip out of town. For those who missed Wood and Water during its initial festival run, an upcoming spring release will provide an opportunity to catch one of last year’s hidden gems.

6. Teenage Emotions (Frédéric Da)

Teenage Emotions director Frédéric Da teaches at a high school in California, and for his first film he collaborated with his students to play out a series of teen dramas: crushes, broken hearts, friendships forming and breaking make up some of the stories in the classrooms and hallways of Teenage Emotions’ school. With a few iPhones as cameras and no script, Da and his students create one of the most authentic portraits of teens in years through a style that adapts to the kids and their environment. Read my full review.

5. What Do We See When We Look at The Sky? (Alexandre Koberidze)

Sometimes all a director needs to do is go for it. Within the first 15 minutes of Alexandre Koberidze’s film, the style switches up so much it doesn’t come as a shock when its two leads get swapped out as well. A sort of modern day fairy-tale, Koberidze uses his story’s initial hook of two lovers cursed with different appearances so they can never reunite to reel viewers in, then spends the next two hours doing whatever he wants. Multiple city symphony montages? Sure. A subplot involving two dogs fighting over where to watch the World Cup? Not a problem. An out of nowhere music video of kids playing soccer? Might as well throw it in too. Koberidze’s digressive approach only works because of how confident and assured he is with each detour, and how each one builds upon the film’s swooning, romantic tone. It’s always great to see filmmaking this bold, especially when it has the talent to reach the lofty heights it aims for.

4. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car (Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Ryusuke Hamaguchi has a knack for defying expectations. Despite having worked since the 2000s, his international breakthrough was 2015’s Happy Hour, a 5+ hour small scale drama that would normally be considered the last thing people might have interest in. Five years later and he brings us not one but two major achievements within months of each other, with the 3-hour character drama Drive My Car becoming an arthouse success despite the ongoing pandemic. Both Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car are undoubtedly two of the year’s best films, and instead of picking which one ranks above the other it’s easier to just put them on the same level.

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy’s anthology structure has each of its three stories center around a sitcom level mix-up or misunderstanding; Drive My Car takes its time developing a relationship before abruptly cutting it short, so its lack of resolution hangs over the rest of the film once its proper story begins. Both take entirely different approaches, but Hamaguchi’s handling of character and emotion lets him dive deep into how grief, loneliness, desire, and other universal feelings can shape us into entirely different people depending on the circumstances. There’s no one else working in film today like Hamaguchi, and one of the few silver linings 2021 brought us was a whole lot of people becoming aware of it.

3. Fabian: Going to the Dogs (Dominik Graf)

In the first hour of Dominik Graf’s Fabian: Going to the Dogs, we see the title character running around 1920s Berlin, bumping into eccentric characters at bars and nightclubs while the camera moves and cuts at a whirlwind pace. It’s a time of indulgence and recklessness for Fabian and other young people in Germany, and then he finds himself standing face to face with a young woman in the back of a club. The camera cuts to a rapid-fire montage of both characters together and in love, scenes from later in the film we haven’t gotten to yet. Up to this point, Fabian was living in the present; without warning he begins to see a future, and we get to see it too.

For a good while, Graf’s film gets drunk on the optimism of up and comers like Fabian, his lover, and their friends, but given the setting of post-WWI Germany we all know how this story ends. Adapted from Erich Kästner’s 1931 novel (which was censored at the time), Fabian sets itself up as a tale about a moralist unable to keep up with the decline of the Weimar Republic. Graf takes that story and turns it into a glorious celebration of idealism before transforming his film into a tragedy of a generation at the mercy of the world to come.

2. Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

With Memoria, Apichatpong Weerasethakul finds himself working on a level of the mainstream he’s never achieved before. Starring Tilda Swinton, set in Colombia (Apichatpong’s first feature set outside his native Thailand), made with his biggest budget to date, and released by one of America’s biggest specialty distributors, this newfound level of awareness has brought with it a strange response. Distributor Neon opted for a roadshow release strategy, travelling to one city at a time, but announced they would never show it outside of a theatrical setting. Then some critics who loved the film went so far as to liken watching it in theaters to a spiritual experience, with some literally dropping to their knees as they watched Memoria on the big screen.

It’s a weird bit of overcompensation, considering a large amount of his fans probably never saw his prior films theatrically anyway. Maybe there’s some confusion over what makes Apichatpong such a singular filmmaker. His films are uniquely cinematic, but because of the way his work uses cinematic language to communicate in ways that push the artform into uncharted territory. Memoria is no different, as Tilda Swinton’s expat in Colombia suffers from an unexplainable illness that eventually brings her to a state of empathy and transcendence that changes how she sees the world. Memoria has a similar effect on viewers with its sublime finale. And while it’s best experienced theatrically (a truism for all movies that’s somehow become a point of debate), to suggest it’s the only way to experience this film does a disservice to the power of Apichatpong and his work.

1. Petite Maman (Céline Sciamma)

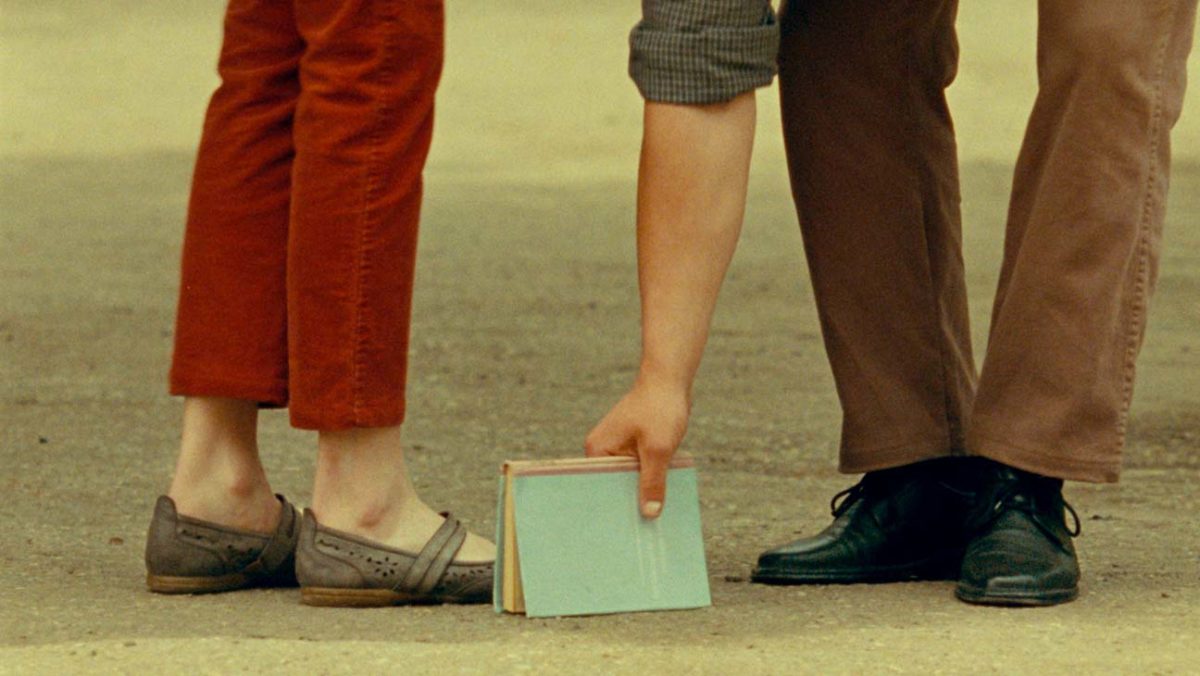

Having made Petite Maman during the second wave of the pandemic, Céline Sciamma had limited parameters to work. A small cast, a handful of locations in rural France, and a limited crew means little room to move within the confines of the real world. But Sciamma, again placing a film from a child’s perspective, didn’t need a lot to work with once she saw the opportunity in the power of suggestion.

It’s there in the way the opening shot, tracking from room to room of a nursing home, provides one glimpse after another of entire lives before the camera stops on a room being cleared out. Or the gesture of a girl feeding her mother snacks while she drives can define their entire relationship. Or how a shot of an empty bed or tacky wallpaper suggests the impossible happening right in front of us, giving its lead character the opportunity to see and interact with the lives of people they would never get to meet otherwise. At its core, Petite Maman is a story of a young girl understanding new, complex emotions in the face of tragedy. But in the intense level of control Sciamma tells this story, where on her terms the limited world of its setting can open up to new and surprising realms of possibility, it’s almost perfect in its execution.