Closing out our year-end coverage is individual top ten lists from a variety of The Film Stage contributors, leading up to a cumulative best-of rundown. Make sure to follow all of our coverage here and see Bill Graham’s favorite films of the year below.

The year of 2013 was a time to look at films in a new way for me. While I enjoyed some experiences more, what I wanted to ponder most as I reflected on this year was what films stuck with me. I’m not one to rewatch films, so it has to make a lasting impression, especially considering the deluge of quality films that releases near the end of each year. When it comes to my list, you may not experience them the same way I did, but you’ll likely remember the time you spent with them just the same. They are wholly unique and sometimes absurdly audacious in their goals. For me, 2013 was a year of discovering the films in between the lines. The fact that Before Midnight, a film that rounds out what I see as the perfect trilogy, didn’t crack my top 10 is surprising to myself. But that’s how the chips fell for me. So, without further ado, let’s jump right in.

Honorable Mentions

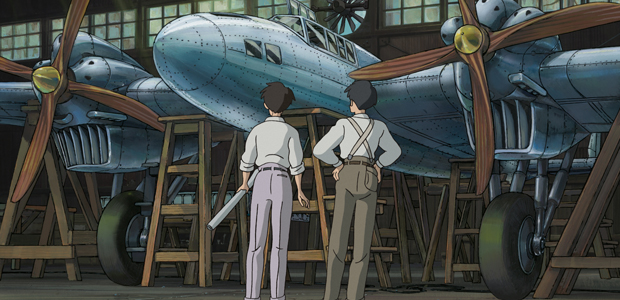

10. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki)

If you showed me The Wind Rises without telling me it was a Hayao Miyazaki film, I might have thought we had a fresh new voice on the scene. Instead, this proves to be Miyazaki’s stated swan song and what a way to go (if he does, in fact, stay away from directing). In between the World Wars, The Wind Rises focuses on the tale of a young Japanese dreamer. He’s ambitious and aims to design the world’s greatest airplanes. But that dream, slowly, becomes warped by the fact that airplanes are newly mastered pieces of war. Chillingly observed, without much of Miyazaki’s notable flair of imagination, this is a quiet film that lets the story truly engage you and dares you to call it just a kid’s film.

9. Blue Is The Warmest Color (Abdellatif Kechiche)

Running a minute shy of three hours, with Blue Is The Warmest Color, we are given a glimpse into young love unlike few films I’ve come across. The purity of desire, of connection, and how that can become hazy as life inevitably complicates matters. While a simple story on the surface, Blue proves that there are nuances to be explored when it comes to love. When the two leads have their first big fight, the messiness and rawness of the scene is so powerful that it threatened to bring tears to my eyes. This is a film that changes and grows up within itself, and it’s brought to reality by actresses Lea Seydoux and Adele Exarchopoulos. Take a bow, ladies.

8. Short Term 12 (Destin Cretton)

Grace, played by Brie Larson, works at a foster care center for at-risk teenagers along with her boyfriend Mason (John Gallagher, Jr.). This isn’t the setting of a comedy, that is clear. Yet, director Destin Cretton finds the small thrills and highs of working there through the lens of two newcomers, one a young girl and one a new worker. While this is primarily Grace’s narrative, the two newcomers would likely threaten to overtake the film and steer it wildly off course in lesser hands. But Cretton navigates this with aplomb and the result is a film that is uplifting while navigating through serious matters of abuse and neglect. It’s an exploration that life is most complex when we don’t talk and harbor our desires, fears, and wrongs. With help, with love, with the passionate care of these workers, we can get through some bad points in life. This is a film that will powerfully shift the way you view what it means to be young and floating through life even when it appears all is right from the outside. Or just the opposite.

7. 12 Years A Slave (Steve McQueen)

Director Steve McQueen has managed to create a narrative-shifting work that explores the absolute corruptibility of slavery. Everything about this institution made the human being seem like a malleable object. Whether that is beating them to a bloody pulp and mauling the bodies of those that did hard manual labor, or poisoning the souls of those it touched and warping people in various, sometimes subtle ways, slavery simply formed those that it touched in the ways it wanted. McQueen has assembled a cast that is impressive and necessary to tell the tale of Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor), and each one seems to play a vital role in how many different shades of darkness there were during this time. Solomon’s narrative is a unique one, but it’s the steady hand of McQueen that allows the film to become transformative — particularly during a sequence of Solomon in a noose — and required viewing for audiences this year.

6. Her (Spike Jonze)

What does technology afford us? Is it the ability to shut out the outside world and focus on what we want, when we want it? Having your iPod earbuds in while you walked around campus was nearly ubiquitous during my time in college. But seeing teachers having to navigate the students’ use of tech in the classroom was harrowing. Was the laptop open for school work and taking notes, or were they playing games and browsing the net? Oh, and please silence your cell phones and put them away, out of sight. Technology is wonderful, until it’s not, but it’s mostly up to us. Her, richly told by Spike Jonze in his solo screenwriting debut, focuses so much on how technology can warp things that people seem to miss the point. Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) is a lonely writer in the near future that finds a connection with a hyper-intelligent operating system that names itself Samantha (exquisitely voiced by Scarlett Johansson). As she learns what love means, he is along for the journey that brings him great joy until he seems to hit the same wall he has with his human relationships. Are we ever ready for love? Perhaps we aren’t, but we’re fools and sometimes we can’t help but rush into situations that are perplexing. Yes, technology can distance us, but witness just how connected the people are in Her when they want to be. There’s beauty all around us in our world. Sometimes even a computer can see that better than we can. Her may not break new narrative ground in terms of the future and our relationship with technology, but as a film it is as rich and nuanced as I could hope, leaving room for interpretation and letting us — the humans — make the connection instead of telling us what to do.

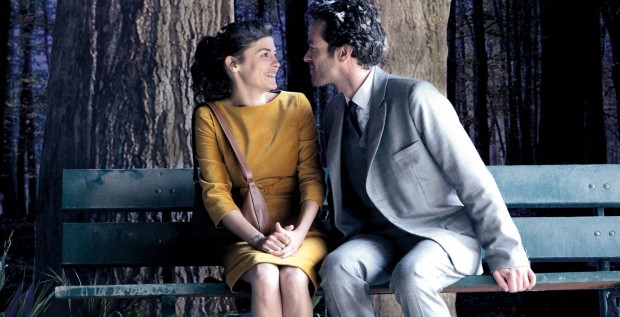

5. Mood Indigo (Michel Gondry)

There is an absolute whimsy to Michel Gondry‘s Mood Indigo and it becomes infectious. If you’re familiar with Gondry’s previous works, you might understand what it means when I say this is his film without restraint. Every piece of the world seems to be alive with vivid color or animated in ways you wouldn’t expect. But the story is, at times, absurd. There’s Colin (Romain Duris), who seems to be well off and living the life of luxury without a worry. He doesn’t even have to work. He’s rich. His best friend, Chick, is obsessed with a writer of some politically fueled nonsense; I don’t know why — he just is. When Chick meets a girl and they connect on their love of that same writer, it inspires Colin to find a woman himself. That’s when he runs into Chloe (Audrey Tautou), and they set off on a whirlwind love story. But it’s the adventure they’re on and the whimsy around them that makes everything even more involving. I felt like I was actually Alice in Wonderland while watching Mood Indigo; at times I even wondered if I was dreaming. To experience this in a theater was transformative because I was absolutely engrossed. But that’s when things change, and the story becomes something else entirely. The whimsy of the world is like a shiny, freshly painted veneer that covers the darkness just underneath. In this world, there are also weapons, sickness, death, and depression. They aren’t nearly as fun to look at, and sometimes downright devastating against the backdrop of the whimsical world of Colin. When we are in love, everything seems right with the world. But the world keeps living, and there is darkness all around us as well. Mood Indigo, as an experience, is one I’ll never be able to shake—because of the whimsy, yes, but also because of the way that can become dulled without the color we are used to.

4. The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese)

Martin Scorsese is an institution by now. So it’s no surprise to me that his outlandish, vulgar, and disturbingly hilarious drug, sex, and greed-fueled orgy of a film got away with an R rating. He’s the kind of director that can wring out performances from actors that aren’t nearly as good as they are in his films. He’s an elevator of talent, or, in Leonardo DiCaprio‘s case, one that is brash enough to give him roles that actually allow the actor to show that he is more than a pretty face. That’s why, when Jordan Belfort (DiCaprio) has the mother of all trips on Quaaludes and ends up in the “cerebral palsy” phase, we witness DiCaprio embrace the story and roll his body down brick stairs in one of the most hilarious acts of physical comedy committed to screen. Many have seen this film as saying that it’s OK to be greedy, but I don’t see how you can confuse this and think it is anything but a satire. Through nearly three hours of debauchery, we witness the rise and fall of Belfort, the true-life “Wolf of Wall Street” during the 80s and 90s. He’s so consumed with making it big that when he eventually does, he keeps setting his sights higher and higher. No one, not even his wife and kids, nor the U.S. Government, pose a threat to him. Joining him on this crazed adventure is Jonah Hill who gives one of his best performances as well. Scorsese hasn’t necessarily made a comedy before, but this is so deliriously wild and insane that it should satisfy those that wonder why he hasn’t made more. But if I’m really honest? I’m just greedy enough to want another.

3. Gravity (Alfonso Cuaron)

Like I previously mentioned, I don’t watch many films again — let alone in theaters, four different times, with four different sets of friends or family, all in 3D. Gravity was a special case. Director Alfonso Cuaron has crafted the modern blockbuster masterpiece, in my view. It’s entirely engaging on a surface level, with the terror of space and its infinite vastness alongside the unpredictability of orbit that can become predictable chaos (just set your watch to it). But Cuaron clearly has enjoyed infusing the film with themes of religion, evolution, and more. What I kept coming back to though, again and again, was the experience of watching this film in a cold, dark theater with a cooperative crowd and being transported to space alongside astonauts Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) as they attempt to survive a mid-orbit disaster and return to Earth. While some have claimed that the visuals are the only stand-out feature and why it is so effective, I understand that keeping this kind of dramatic pressure for 90 minutes is not an easy feat nor one achieved by visuals alone. There’s a narrative masterstroke in what Cuaron and cinnematographer Emmanuel Lubezski have achieved, melding the extended cuts they are known for together with the story. Every shot, every cut, and every sequence was created for a purpose, and the film is propelled forward and then slowed down like a yo-yo. It shouldn’t work, yet it’s all the audience can sustain before they are yanked back into the chaos. It’s at times a bit too “worst day, ever” plotting, but the reward is second to none in my view. I can’t wait to watch it again, and hold my breath during the sequence where Ryan spins out of control.

2. The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer and Anonymous)

People’s actions are rarely black or white in real life. Cinema has a habit of putting those kinds of people on screen, because they let us out of the sticky situation of balancing and passing judgment on people. It’s easy to root for the good guy when he does only good things. And we all know the bad guy. But the most interesting thing you can do, perhaps because it is so rare or perhaps because it mirrors our own reality, is create a grey character. One that, at times, blends both of those things. With this documentary, director Joshua Oppenheimer has given us a grey character that has lived about as dark of a life as one could imagine. During the mid 60’s, a group of local Indonesian gangsters became some of the most notorious death squad members during an ethnic cleansing of the local Chinese immigrants. Among the leaders were Anwar Congo and Adi Zulkadry, who become the subject of the film. What Oppenheimer does is ask Anwar and his buddies to tell the story of their lives during this time. He wants to film their stories, and in order to do so the gangsters decide to play themselves. They grew up loving American gangster films and other genres, and dream of being movie stars themselves. What better way to do this than act in the reenactments? So they decide that’s how they’ll tell their story. All along, Oppenheimer is filming them throughout. Within this, we bear witness to the attrocities that they admit to and often reenact in a gruesome and surreal way. The documentary becomes nightmarish at points, and exposes what it means to be the person that commits these attrocities. People are people at the end of the day. Even the worst ones likely have family, friends, and loved ones. Whether those people are blind or fully aware doesn’t matter. As the film progresses, we witness a change in Anwar that has disturbing consequences for the audience. You can call these people monsters all you want, but they don’t have scales. They’re flesh and blood, like you and I, and that’s perhaps the scariest thing of all.

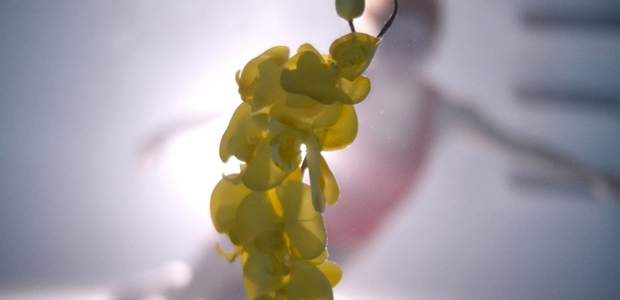

1. Upstream Color (Shane Carruth)

This will likely be the most difficult film to explain to someone that either hasn’t seen it or didn’t understand upon first viewing. It’s hard to justify a film as airy and dreamlike as director Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color, but what an achievement it is. Whether you want to talk about the science fiction aspects of the various things within the film, like the Sampler or the parasite that links our two leads, or if you’d rather focus on the love story that might actually be fate or the unintended consequences of the parasite’s life cycle, there’s myriad ways to jump into the film. But more than anything, I think it has to be the masterful control that Carruth displays that is one of the most impressive feats of the film. After all, he served as writer, director, actor, producer, cinematographer, editor, composer, casting director, production designer, and sound designer on the film. That he also self-distributed the film, then, should come as no surprise. Carruth was a man on a mission by all accounts, and he displays an uncommon confidence that his narrative, as fractured and confusing on the surface as it might be, will meld and gel near the end to create an experience that works on multiple levels. He doesn’t treat his audience like idiots, but he also suffers no fools. This, to me, is what smart science fiction is all about. This is Carruth’s story and it is decidedly unique in how it goes about itself and plays by its own rules. This opens the film up for conversations about what it all means, and how it works or doesn’t work. It’s a film that you want to tear open and investigate over and over, and you get the sense that it is welcoming you to do so because there appears to be genuine intelligence behind it. It’s a Rubik’s Cube of a film. For some it will be utterly confusing and complex, but for others it will be a rich, challenging experience unlike anything else.