Chan Is Missing has long been considered a benchmark in Asian-American cinema — some would say that, unfortunately, it’s by default the benchmark — but, 34 years later, writer-director Wayne Wang mostly has other things on his mind. Speaking to him on the occasion of that film’s Metrograph run, Wang was more keen to talk about what he’d wished to do with the movie, other movies in his filmography, and what’s happening elsewhere.

The film absolutely deserves your time and attention, and Wang’s attitude is more telling of where his career has gone: many places, and, more importantly, where he’s wanted to take it. Read my discussion with him below.

The Film Stage: After so much time, has Chan Is Missing ceased to yield anything new? Or do you still discover new things?

Wayne Wang: Well, you know, everything about the Chinese-American community has changed. Filmmaking has changed. I just recently resew the film because of the screening; I was cutting a trailer. I still had a lot of fun with it. I want to redo it, as I want to redo all my films. Otherwise, I don’t mind the film. It’s hard to talk about it because it’s so far away. The things that I do want to redo is that, originally, it had a more structural element to it that I couldn’t pull off at the time, but it’s fine that it is what it is.

What is this “structural element”?

The film was originally an application for National Endowment for the Arts. When I wrote the application, I wanted to make a mystery that was based on the development of the Chinese written word, which is in the interest of Eisenstein’s montage theory. Basically, in the first stage, everything is based on the image. The second stage is pointing to the situation. To point to the situation, you would draw a knife and add a stroke to indicate the edge. The third is the meeting of the ideas, which is Eisenstein’s montage theory: you take a picture of a knife, and then, let’s say, a picture of a person’s heart, and you put a knife on the heart.

It becomes patience, the meaning of patience, because patience is an emotional concept that you cannot draw. The combination of images to express that — the meaning of ideas. The fourth part is the relationship between picture and sound: an element of sound coming in. A movie about pictures and sounds. Anyway, I wanted to make a mystery that had at least four structural changes. Intellectually, it was interesting, but because of a lack of money and being able to experiment with stuff, I couldn’t pull it off, so I made a straightforward mystery instead.

Metrograph’s description calls it “a milestone in Asian-American cinema.” Has this status affected your way of seeing your work?

When I was at film school, there were no true representations that matter. If you look at it, it’s all Fu Manchu and characters like that — pretty stereotypical. Images in the media about Chinese-Americans… it was kind of a burden on me, and there were no other filmmakers doing that. Ang Lee did a couple in a similar context, but there were few doing it. So I carried it for a while, until I did The Joy Luck Club and a few other things, because I didn’t want to be boxed in. So I took off and did different things and all that.

Are there recent examples of Asian-American cinema that you find worthwhile? Even ones where you can recognize traces of what you’d done?

It’s been hard. You know, mostly because my feeling is that the American independents are so about storytelling and trying to be more stripped-down, minimal narrative, but, basically, they’re very narrative. I remember films of that time — such as Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise — and they were very interesting films, narratively.

These days, I look at student graduation films and the films are really wild and crazy. I miss that and I see that more in some interesting European films, more than anything else. In my days, I was also very much influenced by Godard and his whole theory that film language isn’t just one language that Hollywood has dominated, but one that can be very diverse, and, in montage theory, you can watch just a lot of images rather than always accepting what these images mean. These days, it’s completely dominated by the Hollywood narrative.

How do you think you’ve changed in the decades sense? How has your sense of form evolved?

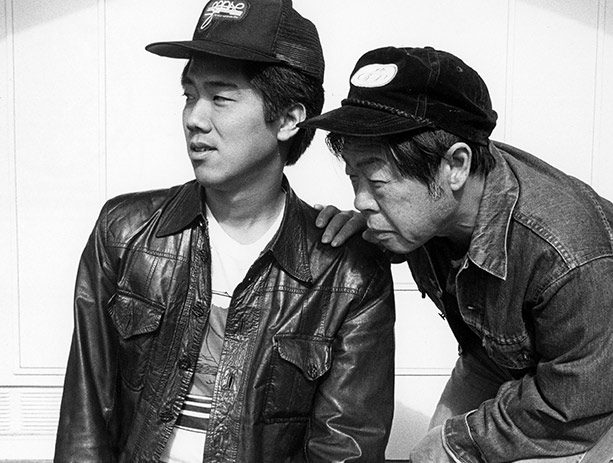

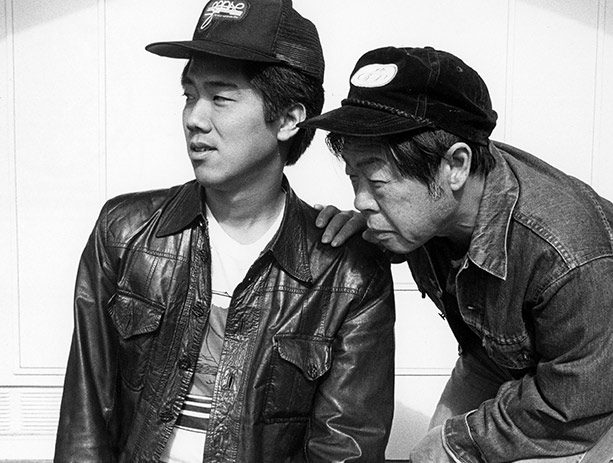

My form has not evolved, really. Well, yes and no. I would say that I think, for myself, what’s important is that I’m still “the one” that sort of makes films about the Chinese-American community. I’m proud that I did a lot of different kinds of films; if you look at my career, I just jump around a lot. More recently, I’ve come back to experiments. I did a documentary called Soul of a Banquet that’s about a 93-year-old; I did a film in Japan with Takeshi Kitano. I don’t know if I think of myself… over the years, I’ve stripped myself down to a minimalism.

Chan makes great use of San Francisco, and I’d like to hear your thoughts on the city’s place within cinema film.

San Francisco has been, kind of, the outsider and rebel for those who don’t want to be in L.A. — and I count myself, because I hate L.A. and don’t want to live there. Some, like Coppola and Lucas, have made their career there. You also have George Kuchar and others. San Francisco has always had this attitude about being different, and that’s the beauty of it.

Do you have memories of coming up with other filmmakers?

There was one day in time that I really remember well. Chan Is Missing was selected to show at the Edinburgh Film Festival, and I went there. Edinburgh is such an interesting city and I’d never really traveled much through Europe at that time, and that’s a festival where I ran into Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang. Everyone was coming out with their new films at that time, and we all had lunch at a fish and chips shop. We talked about Taiwan, China, our films, our ideas. I met Ang Lee when we were both struggling. I met a lot of younger Chinese filmmakers. There were some really young filmmakers there.