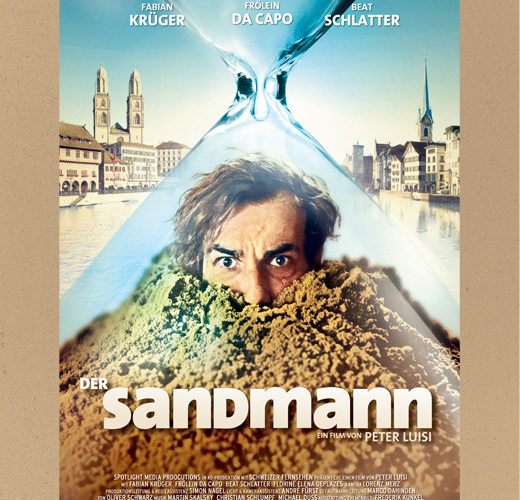

What would you do if you woke up one morning to find sand in your bed? You haven’t gone to the beach and you didn’t do anything at night besides dream a very realistic dream with sun and sights. Your boss at a local stamp collecting shop made mention of seeing granules around the front desk—saying he’d like to kick the knee of whomever is bringing in such dirt—your doctor gives you a clean bill of health, and your shrink thinks you’re sharing a nicely constructed metaphor on your life. All this is what Benno (Fabian Krüger) must contend with in Peter Luisi’s Der Sandmann [The Sandman], screened at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Dealing with existentialism in a very Kafkaesque way—bearing a resemblance to an odd film from a few years back called Bartleby—Benno begins to think he is going crazy, unable to come up with a reason for his inexplicable ailment. To his surprise, the motivating factor may end up being a bit more obvious than he’d like to believe and the cure in the possession of a young barista working at the coffee shop below his apartment.

Benno is not an especially wonderful specimen of humanity. He toils at his menial job, taking pride in ripping off customers who come in without a clue as to the worth of the collections they’ve inherited from deceased relatives. His girlfriend Patrizia (Florine Elena Deplazes) is young and attractive and his friend Stefan (Sigi Terpoorten), a composer, for some reason puts a lot of stock in his musical eye and ear. We see a glimpse of dream where Benno is conducting an orchestra before his hearing is lost and the adrenaline rush turns to abject fear. In real life his ear is sensitive to all sounds, finding it difficult to sleep when Sandra (Irene Brügger), the girl below him, closes shop every night to practice her one-woman orchestra maneuvers. She desperately is attempting to ready herself for a local talent night, but his shouting, banging, and constant stream of insults slowly chips away at her confidence. Who is this jerk to tell her if she is talented or not? When posited with this question, Benno appears to want to tell her about his past and why his taste should be respected, but he quickly stops himself.

So we are thrust into his life, watching as he slogs through it, depressed at his current lot, wishing for days past. And then comes the sand. At first simply a small pile beneath him in the morning, his loosing of the substance increases each day, his lying making the steady stream even more voluminous. He has taken things for granted, become bitter, and has inflicted this mentality in all aspects of his life. He keeps things civil with Patrizia, white lies seeming to populate every word he speaks to her; he bullies his co-worker Walt (Kaspar Weiss), a man who truly finds pleasure in finding rare stamps; he steals from his boss (Beat Schlatter), lying through his teeth when confronted; and even when Sandra isn’t singing—but making his coffee with hot milk—he continues berating her, taking some sick pleasure in her scowl and absolute disgust at this vain man walking through life with a chip on his shoulder. Despite all this, though, when the sand refuses to stop, he begins to turn to those around him, thinking they can help when he has only ever earned their hatred.

The beauty of Luisi’s script is its use of comedy. While the main plot concerns this man seeking redemption, his journey towards that end is full of humor as he begins to use the power of his sand for wrongdoing. Discovered by accident, Benno finds he not only looses the sand, but he can also inflict slumber with it. The title, The Sandman, then doubles as both a literal ‘man of sand’ as well as the fictional character helping people sleep. When things happen that he can’t control or when situations spiral out of it, Benno takes some sand and shoves it in the face of those opposite him, cleaning up the mess and leaving them to believe they dreamt the entire thing. It’s a trick he uses often with his boss when lies create more and more sand, eventually filling his taped off clothes to their breaking point, letting loose all over the stamp shop. But while he causes others to sleep to make reality easier, he never really looks at his own dreams until forcing Sandra to pass out, finding her moan his name on the floor of the coffee shop.

As it turns out, Benno and Sandra have connected through dreams and neither is too happy about it since their real life relationship is anything but pleasant. In the dream they are a couple, happy and in love, he a conductor and she a singer. They entertain friends, laugh, and seem absolutely happy—the one thing their characters are not when awake. Benno can’t reconcile the fantasy with his lifestyle, his sand problem becomes more volatile, ruining his life and filling his apartment, and his attempts to get answers from a television physic named Dimitri (Michel Gammenthaler) only frustrates. The point comes when he forces himself to sleep so he can find an answer in his dream. Krüger and Brügger fantastically juggle spite with compassion as Luisi gives them the story to evolve as well as the visuals to keep his audience on their toes as the sand grows as Benno wastes away. The credits begin with Krüger in slow-motion, deservedly getting a cup of coffee thrown into his face, yet somehow Luisi still makes you want his metamorphosis to succeed on its Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind-like journey, making Der Sandmann an intriguingly worthwhile surrealistic allegory.

The Sandman is currently playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival.