“According to the experts, men are very fragile.”

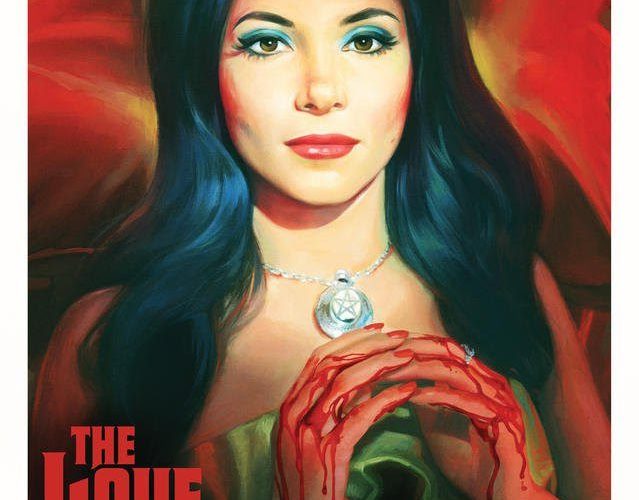

Shot in sumptuously lit 35mm, The Love Witch is a throwback to Hammer Horror films and Technicolor melodramas of the ‘50s and ‘60s, with set design and color schemes that seem to invoke the ghost of Jacques Demy, all in subservience to a decidedly retro ‘70s vibe with a contemporary setting. Only writer-director Anna Biller‘s second film, The Love Witch affirms not only her skill as a director, but as an auteur – Biller also produced and edited the film, and was responsible for every aspect of the production, art, and costume design, and even composed the score.

The film exists in extravagant sets and costumes that run the gamut from kitschy to dazzlingly beautiful, dresses bursting with color, and every background and set piece a delight. Harps float over a tea room of pastels and pink, eminently feminine; a medieval Renaissance is played out in the woods, replete with lyres and lutes and love songs, murder and mystery and noirish back-story are all rolled up into one. The Love Witch is set in the heart of California and concerns a forlorn witch, Elaine, who seeks to begin a new life in a small town far away from her painful past in San Francisco. Elaine is brought to life with a stark, vividly lived-in performance from Samantha Robinson, whose prim visage and courtly manners belie the madness in her eyes. Channeling the grace, gravitas, and the duel balancing act of melodrama and satire, Robinson emerges from the film a star.

A glamorous femme fatale writ large, she is one of the more complex big-screen female characters in recent years. Elaine describes herself as such: “The Love Witch — I’m your ultimate fantasy.” Armed with the knowledge of the arcane arts and a one-track-mind, Elaine has the sole purpose of finding a man who can give her an equal outpouring of the love she wants to give him. From a bumbling college professor to her friend’s husband to a cop hot on her trail, Elaine falls in love effortlessly and wholeheartedly. Her love, though, has the unfortunate side effect of killing her paramours. Her first target, the professor Wayne (played with a goofy naiveté by Jeffrey Vincent Parise) is so distraught that he dies of a broken heart. He collapses into tears after lovemaking, exclaiming over the intensity of his emotions until he dies, and so his heart couldn’t keep up with her love coursing through his blood. Parise shines here, with his simple-mindedness and broad, expressive facial expressions, which remind me of the dimwitted frat boys from Whit Stillman’s charming Damsels in Distress. The bumbling men are often given some of the best lines and moments when confronted with the raw, naked power of their own narcissistic and lustful impulses.

The film takes root at the moment of Wayne’s seduction and death, as the audience is able to see both the power and destruction wielded by Elaine, as well as the odd effect her love potion has on the men in her life. Men here are enchanted by the female form, but also wary of it — evidenced best in hilarious dialogue delivered straight, e.g. “Did you know most men have never even seen a used tampon?” The Love Witch springs back and forth between fantasy and reality, seduction and desire as magical and powerful in a primal way, albeit with the help of a few potions and rituals. The camera lingers on the eyes, or cuts to them frantically, some unseen magic present in the gaze of a lover. It flits back and forth between the male and female gaze, from voyeur to provocateur, and back in an instant, sometimes even the same scene. The film thrives on role-reversal, doublespeak, and the constant scent of death and despair lurking underneath its lush perfume.

Symbolism is scattered around. Elaine knows no boundaries in her pursuit of love, lusting after that which, according to her, should be as simple as sexually providing for men. As she seduces a man, she asks what turns him on. His answer borders on the absurd: “Like one of those Westerns where they shoot up the town and then visit the local prostitutes.” She replies in a sing-song voice, “That’s very sweet.” She’s so committed to giving men what they want, convinced that’s the only way to win one. Staunchly feminist, it’s a film full of these extremely gendered statements that some would consider passé, constantly pushing men and women apart from each other and firm in recognizing differences between them. Elaine is powerful because of her feminine sexuality, but, even then, cannot use it to change the hearts of those she wants love from; even in her power she can’t get what she wants. Sex is seen as freedom from that, because, according to Elaine “All my life I’ve been tossed in the garbage except when men want to use my body,” so now she uses her body first — before they get to control her. Yet the film itself is never overtly politicized; rounded characters and a frothy plot coexist easily with the subtext, allowing the film to be feminist even as Elaine may perfectly well be a sociopath.

The Love Witch stretches past its bounds with a running time of two hours, trying to fill the film with too much when it’s already stuffed to the gills, particularly in drawn-out pagan rituals and parties that never quite coalesce with all else; it would have made an even lighter and more pressing film at 90 minutes. Yet even as it stands, Biller’s work is light on its feet, delighting in its own sensuality, basking in gorgeous colors that seem to have bled through the screen from another age, and coyly seducing the audience before hitting them over the head with a hammer.

The Love Witch played at the Vancouver International Film Festival and will begin its U.S. release on November 11.