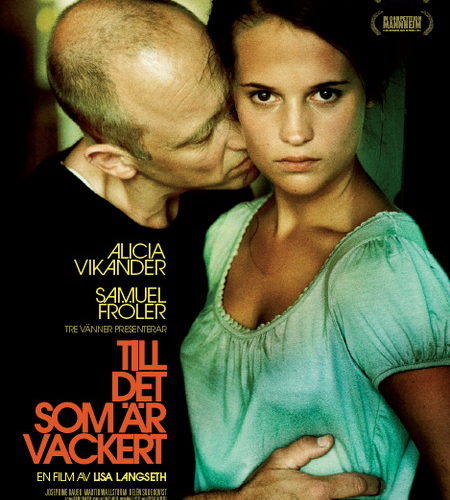

What’s worse than giving sex to a married man for money? Giving it for love. It’s a tough distinction to delineate for a reformed twenty-year old prostitute whose only role model growing up was a drug-addled, suicidal mother that more or less taught her the business. Hoping for redemption and a ‘cleaner’ life, Katarina (Alicia Vikander) has vowed to never go back and instead cherish her boyfriend Mattias (Martin Wallström)—the one decent male in Sweden who doesn’t yell whore at her on the streets. Unfortunately, while the purity of one’s soul and a genuine hope for love is nice on paper, finding it quickly after the hardships endured from her past is unrealistic. She is too susceptible to kindness; too willing to believe anyone outside of her suburban slum is good. While the title may be Till det som är vackert [Pure], the lead character is anything but.

Known now because its star Vikander is hitting Hollywood casting agent lists hot on the heels of writer/director Lisa Langseth’s stageplay original’s muse—Noomi Rapace—Pure deserves to be seen on its own merits. Chock full of classical music and philosophical nuggets, the heavy-handed quest to reform a troubled youth through art might be too much for some. To me, though, it fit the plotline perfectly, especially since Katarina lucks her way into working the reception desk at the philharmonic concert hall in the city. Befriending the conductor Adam (Samuel Fröler), she finally feels welcome inside the world. Saying ‘hello’ to the musicians, becoming the pet project of her boss Marie (Helén Söderqvist), and finding a smile where only the scowl of too much suffering had once appeared etched permanently, Katarina may have found her true calling. And it was all due to a Youtube clip of Mozart that melted her soul.

But her past can never be fully eradicated. Mattias tries hard to bring her mother back into the fold, an idea that backfires and only serves to drive her further away. The concert hall is her sanctuary; the music played a drug coursing through her veins. And at the center of it all is the maestro. Renowned and loved by the public, Adam sees Katarina’s desire to work hard and her ability to look deeper into things as endearing. Such fervor for the things he loves only helps him break down defenses and take her under his wing by lending books and music. They meet for coffee, laugh and joke in the lobby, and talk about real things rather than television shows or videogames like her boyfriend calls ‘art’. It’s a friendship that gives way to secret looks and sexual longing. Adam is a professional who sees her as more than the streetwalker her contemporaries refuse to let her forget.

Through minds like Kiekegaard, he teaches her to follow her dreams and stop at nothing to earn what she deserves. He floods her mind with ideas of reaching heights unimagined, touching her on a psychological and emotional level; he is not merely a John she can give a blowjob too and go on with her life. So when he takes her hand to find a secluded part of the auditorium and invites her to his home while his wife and child are away, she grabs hold and refuses to let go. What is she to think? Men have always ignored the bands of metal on their ring fingers for a romp with her. This is normal, yet also good. A love she has never felt from anyone is showered down and that brief taste is all she needs to feel wanted. Breaking that bond by destroying an impressionable youth at the height of love’s warmth earns you the clingy, stalker ways to follow.

Just as you acknowledge the theatrical feel by focusing on these two characters, you also sense the lengths Langseth went in order to make it naturally transition into a fully formed world. Throughout the multiple sets and numerous supporting players, though, the spotlight never leaves Vikander. A performance earning every accolade, this actress truly is a revelation carrying the work higher than maybe merited. Similar to many cautionary tales about disturbed, sexual creatures unable to differentiate between love and lust, the themes used aren’t too unique. The story points rarely delve into fresh territory either with an adulterer taking advantage until it suits him to stop while the victim is left in a state of absolute confusion. Fröler handles his role in such a tandem perfectly too, giving equal parts compassionate love and self-centered hubristic destruction.

So vulnerable, naïve, and closed off to certain realities, Vikander’s Katarina is ripe for the picking and Fröler’s Adam knows it. Excelling in the quiet moments of introspection with watery eyes from both the euphoric bliss of song and the rage-induced darkness shrouding her mind from redemption, Vikander steals each scene. Strong yet soft, radiant while tumultuous, the role isn’t an easy one for any actress let alone one in her first feature length theatrical film. The idea posited that she will do whatever it takes to survive is one that allows such range of emotion, the borderline insanity letting the stakes divide it further. Powerful from start to finish, Vikander eventually becomes bigger than the film itself, her confusion in how to reconcile the need for a job she loves and a man to love of greater import than what happens to those in her life.

However, their actions shape what she is willing and able to do. The hurricane soon to rip through her being can be seen as her own doing, but the idea she tried hard to overcome her limitations should be taken into account. Sadly, I believe Langseth puts too much weight on Katarina’s capacity for change and too much evil into the actions of Adam—no matter how despicable. In a rousing scene of blaring strings and Vikaner’s baton miming in front of an open window, we are caught in the swell and anticipate the worst. The reality is too dark, though, as the film unacceptably almost condones amorality. I understand what Langseth is trying to accomplish but believe she forces it unnaturally. People do deserve second chances—this much is true. As a result of the disarming final frame, one must wonder if such sentiments are true. Humanity may in simply be intrinsically evil and the cycle of opportunistic monsters cannibalizing themselves without an end in sight.

Pure is currently playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival.