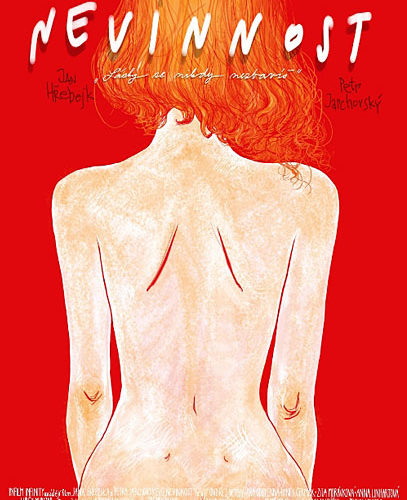

According to the program for this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, director Jan Hrebejk and writer Petr Jarchovsky have visited many times with their collaborations. What is different this time is the type of film they have brought. Supposedly beginning a new trilogy in “blame and punishment”, this psychological thriller is new territory for their oeuvre and if the next two are as good or better than this, I say they shouldn’t stop at just three.

On the surface Nevinnost [Innocence] is a tale about the sanctity of a young girl’s word. Olinka (Anna Linhartová) is quite obviously a disturbed girl with a fanciful imagination, but when she accuses her physical therapist of abuse—or in her own words, love—the law doesn’t allow you to laugh and assume slander. No, in terms of a crime such as this, even the smallest chance of truth means you’ve must take the shot at stopping it from happening to anyone else. But when the policeman assigned to the case is the accused’s old childhood friend as well as the man he stole his wife from, tensions will run high. What should be an objective case of he said/she said becomes a battle of escalating emotions as Láda (Hynek Cermák) does his best to not seek revenge through the investigation and Milada (Zita Morávková) sees red with her current husband held in prison by her ex.

What’s introduced as an idyllic family via photo portrait soon shatters into the impassioned patchwork of ideals and opinion it has become. Gone are the days of happiness and joy, the entire clan visiting their summer cottage for fun in the water and sun. Now all that remains is an invalid patriarch (Ludek Munzar) too proud of his medical-bound grandchild and doctor daughter to accept her sister’s career move towards charitable performing clown to sick kids; that clown, Lída (Anna Geislerová), holding a blatant sadness in her movements and expressions as a result; her sister Milada, the adulterous who ruined her marriage, now wondering if her new husband is having another affair; and said womanizer, Tomás (Ondrej Vetchy), working as a rehabilitation physician for young girls and a bit too active with his fifteen-year old daughter’s friends.

Details are carefully laid out as Innocence progresses, small tidbits of information shedding light onto how this once joyous family has become full of bile and distrust. At the center lives the young girl who has fallen in love with her doctor: a fanciful fourteen-year old who makes up stories about how her mother threw her down the stairs. When we meet the woman, so kind and generous giving the doctors and nurses gifts for helping heal her child’s leg, we know it’s a lie. Tomás’ nurse even tells him about conversations with the girl about aspirations to become a writer with short stories and poems written about a character named Ariadne. Dismissed as a playful youth with a wild imagination, we think nothing of it until the accusations rain down. And when Láda becomes involved, he has seen too many abused/raped girls in his day-to-day on the streets. He must find out the truth.

Hrebejk and Jarchovsky work their magic as they weave this tapestry tight using every single character and leaving nothing to chance. With Olinka knowing details about Tomás and Milada’s house no one who hasn’t been there would know, we in the audience begin to suspect as well. We see this doctor at his daughter’s birthday party, kissing her and throwing her into the pool as he chases her friends in a game of bikini-clad musical ping-pong. It is horrifying, but our minds automatically begin to think the worst when heavy subject matter is displayed. By the time Olinka’s mother finds her illicit diary, we have already sentenced him guilty with the ‘a-ha’ bells dinging loud. But should we be so quick to judge? Should we be like Láda’s police chief, giving him the case as though it were a present for retribution? Is humanity truly that hopeless?

The lies help uncover truth throughout this fascinating journey between fact and fiction as the filmmakers manipulate us with every frame. Twists and turns abound while learning how Tomás stole Milada and exactly why Lída quit medicine. The deeper we delve into the Walter family, the darker the abyss becomes. Fifteen years have gone by since the fracture occurred, leaving Láda alone and removed from his home. Fifteen years have passed of awkward comings and goings as their mentally handicapped son rotates between their custody and his assisted living home. Fifteen years of bottled up feelings of love, hatred, and regret stew until they can no longer be contained. Once the truth starts to flow, it cannot be stopped. And when the revelations we discover are made known, the fact this family has kept up appearances for so long is a miracle; or perhaps more aptly a curse.

With stunning performances from all, I would single out Geislerova, Cermák, and Linhartová the most. Yet even as I type those names I remember an exchange between Cermák and Morávková that stirred my blood, her vitriol so strong in its misguided spite. Even Munzar has moments through his dry impatience, calling Lída ‘Jester’ and never stopping to note how wonderful her sister and brother-in-law are in comparison. What gives them such success is the intricate web woven for them to act out through its carefully constructed mirroring of past and present with long-awaited karmic retribution. The eventual discovery of truth and lie blurred together will captivate in its subtlety while frustrating in one character’s long-winded expository description of what we’ve already guessed. It’s one more example of filmmakers distrusting their audience whether consciously or not. A misstep that tarnishes the whole from full marks but doesn’t prevent our appreciation in the level of intelligent storytelling at play.

Innocence is currently playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival.