When sitting down to watch The Look of Silence – Joshua Oppenheimer‘s follow-up to 2012’s harrowing The Act of Killing – you’re struck by how quickly you can slip back into the particular brand of uncomfortable captured by its predecessor. The laughs, the jarringly playful recounting, the unblinking eye of the camera – it’s like a nightmare you find waiting for you when you go back to sleep, astonishingly unchanged.

And yet it only takes a few minutes to fully comprehend how The Look of Silence is complementing and expanding the subject, and why Oppenheimer is not letting this go. The director famously tracked down some of the perpetrators of the Indonesian mass killings that took place in 1965 and persuaded them to re-enact their atrocities on camera. For this film, he’s bringing the victims into the equation: Adi, a 44-year-old optometrist whose brother Ramli was murdered in the purge, and his mother, who’s left tending to her centenarian husband and still remembers everything about the day she lost her son.

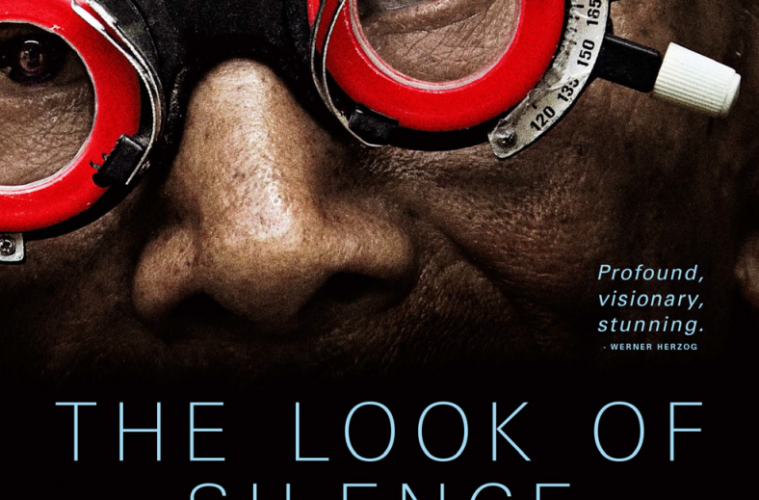

Observing their routine interactions with Adi’s father and daughter, interviewing them privately or putting them in a room with the killers and their own families, Oppenheimer introduces a key differentiator in his prolonged investigation. In a probably-too-neat piece of symbolism, Adi is often seen performing eyesight tests on people (the repeated close-up of squinting eyes framed by test glasses is the dominant image of The Look of Silence, as the giant fish was to The Act of Killing) and it is indeed affecting to witness his gentle attempts to make the killers see and come to terms with their actions.

Structurally, though, it’s the audience that’s being tested with the application of multiple lenses – those of common sense, human emotion, and even doubt and skepticism. After all, everything in The Act of Killing was re-enacted, even those rare glimpses of self-awareness. Here, Adi’s role somehow mediates and re-contextualizes the issue through language, giving voice to impulses that were shut out from the pressure-cooker experience of the previous film. It’s a striking development, a subtle switch from the ritualistic to the dialectic that simultaneously justifies the film’s existence and renders it more dependent from the first one.

It goes both ways, too. Even the perpetrators and their families engage on this whole new playing field, telling Adi that “Josh never asked questions so deep” and even warning Oppenheimer that he’s “not welcome anymore” as a result of such probing. If it’s true that The Look of Silence reaches even further than The Act of Killing, it’s also clear that the approach used this time around wouldn’t be as effective without those powerful foundations. Just like in therapy, you’re only ready to question and discuss your traumas once you’ve re-enacted them enough times.

The symbiotic relationship between the two films makes a critical assessment of The Look of Silence especially tricky. Much like those beautifully-composed shots of Adi sitting alone in an empty room in front of a screen, we’re all still entangled in the act of watching the act of killing. But beneath the brutal simplicity, and even the inevitable lingering, Oppenheimer’s filmmaking style finds ways to grow more daring.

The Look of Silence premiered at Venice and will hit theaters on July 17th.